- 91 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

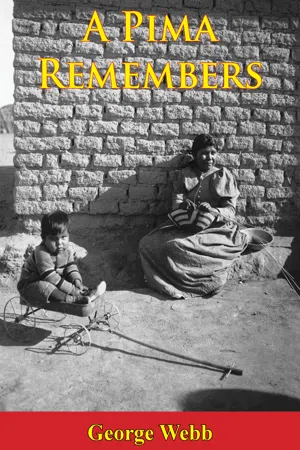

A Pima Remembers

About this book

The lifestyle of a people, preserved in the memory of a Pima whose life ran from the late 1800s to the Space Age. The universality of man's eternal hope of betterment is reflected in the wisdom of the Pimas:

So now I hope

You will strive

To make this day

The best in your life.

George Webb.

"…a book which seems to have grown right out of the Arizona earth—anecdotal, almost artless in its directness, but having the impact of reality…a flavorsome re-creation of things past in the life of a friendly, generous people."— The New York Times

"George Webb's gentle recollections of his childhood and Pima Indian lifeways will doubtless endure forever. This deeply moving autobiography is the perfect introduction for younger Pimas to their culture and history." —Arizona Highways

"This extraordinarily pleasant and amiable narrative wakes vivid an ancient and happy way of life"—Oliver LaFarge

So now I hope

You will strive

To make this day

The best in your life.

George Webb.

"…a book which seems to have grown right out of the Arizona earth—anecdotal, almost artless in its directness, but having the impact of reality…a flavorsome re-creation of things past in the life of a friendly, generous people."— The New York Times

"George Webb's gentle recollections of his childhood and Pima Indian lifeways will doubtless endure forever. This deeply moving autobiography is the perfect introduction for younger Pimas to their culture and history." —Arizona Highways

"This extraordinarily pleasant and amiable narrative wakes vivid an ancient and happy way of life"—Oliver LaFarge

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

A PEACEFUL LIFE

WAY out in the southwestern part of our country which is now the State of Arizona, there was a Pima Indian Village.

It was a day in the early part of spring. The desert was covered with green grass and the trees were just beginning to put forth their leaves. The sun had been shining brightly and was now low over the horizon.

Juana Losso stood on a little knoll not far from her brush home. With hand shading her eyes she was looking towards the distant hills watching for a glimpse of dust that would tell the return of her husband Eaglefeathers from a hunting trip. Beside her was a little boy of two summers whose name was Keli•hi, which means “Old Fashioned.”

Not seeing any dust Juana Losso and her little boy walked slowly back toward their home.

Just then two other boys came running over the desert. They were also sons of Juana Losso, and older than little Keli•hi. With them was a dog.

Grayhorse had a cottontail rabbit hanging from a cotton string tied around his waist. Swift Arrow had two quail hanging from his cotton string belt.

This cotton string belt the boys wore held up their gee-strings, the only clothing the Pimas wore in those days. Juana Losso wore the usual dress of the women which was a cotton cloth wrapped around her waist hanging down to the knees.

The boys and their mother were all barefooted, although sometimes they wore sandals made from cow or horse hide.

Grayhorse and Swift Arrow were both talking at the same time trying to tell their mother how they had killed the rabbit and the two quail.

She listened. Then with a little laughter she took the rabbit and the quail to clean.

After she had cleaned them, she sharpened the ends of a stick and stuck it through the rabbit lengthwise. With the quail she did the same and put them up to the fire to cook.

While the rabbit and the quail were cooking, Juana Losso went to the storage-basket and took out some vi-hog (mesquite beans) and pounded them into a powder on the chu-pa (mortar). This powder was mixed with water and used as a sweet drink.

Sometimes the powder is put into a clay bowl, sprinkled with water, and covered with a damp cloth to harden into a cake when dry. This cake is put away and kept in store for winter. Eating a small piece of this cake, a Pima could go all day without other food.

The cooking of the quail and rabbit was now done, so Juana Losso with her three boys, Grayhorse, Swift Arrow and little Keli•hi, and their dog Tua-chinkam sat around the fire to eat.

The dog suddenly sat up and looked out into the darkness.

They all stopped eating and Grayhorse and Swift Arrow jumped up and ran to meet their father who had come home with a deer.

After Eaglefeathers unsaddled his horse and hobbled it out, they all went back to the fire. Grayhorse and Swift Arrow were both trying to tell their father how they killed the quail and rabbit. Grayhorse was telling how Tua-chinkam chased the rabbit into a bush, keeping it there by barking while he shot an arrow and killed it.

Swift Arrow was telling how Tua-chinkam scared up the quail and how they flew into a tree and sat there while the dog kept barking at them.

“The quail just sat there while I picked out my best arrows and shot them, two of them with only two arrows!” said Swift Arrow.

The boys patted the dog who had helped them.

In those days Pima boys learned to use the bow and arrow when they were very young. That is how they became experts when they grew older.

The boys hunted separately from the older men. Their game consisted of small birds, such as doves and quail, and also cotton tail rabbit.

They did not make their own bow and arrows. A grandpa or an uncle always made them, of a size fitting the size of the boy.

The little Pima boys are proud to carry a bow and arrows made by Grandpa. They learn to use it by shooting at a target, called wulivega, which is a small bundle of grass wrapped with willow or mesquite bark about six inches long and two inches around. The boys throw the target ahead ten to twenty feet, each boy taking his turn in shooting one arrow at it.

Juana Losso now began to cook a piece of the deer meat for her husband.

Her cooking place was a round shelter of arrow-weeds stuck in the ground, held in place by a few willow or mesquite posts. The fire was built in the center, with clay pots and ollas of water and food around it. Most always this enclosure was under a mesquite tree.

The Pimas in those days seldom ate a noon meal, only a little cactus syrup with whole wheat bread or chu’i in the early afternoon. The evening meal was eaten whenever the men came home from the day’s hunting or work in the fields.

They cooked the meat by holding it over the open fire or placing it on the live coals, at other times burying it in the hot ashes.

Here I shall tell how a Pima cooks rabbit in the ashes:

First you dig a trench in the ground, a little bigger than the rabbit. Build a good sized fire in and over the trench. Then clean the rabbit in this way, leaving the skin on: cut the stomach open just enough to take the intestines out, but leave the heart, liver and as much of the blood as you can. After getting the stomach cleaned out, take a small green stick, sharpen one end and use this as a pin to close the cut.

By this time the fire has burned down leaving hot coals. Now take a long green stick and push the coals out of the trench leaving a few at the bottom. Then place the rabbit in the hot trench, bottom side up, and cover over with hot ashes and coals. Rebuild the fire on top and let it cook for about forty minutes or more as depends on the heat of your fire. When the fire dies down, take your long stick again and take the rabbit out. The skin will pick right off. Then eat! You will find that a rabbit cooked in this manner tastes very good. Especially when you are hungry.

A vato or shade was usually just a few yards from this cooking place. This shelter of a type still used by the Pimas was made with four or six upright forked posts that held cross-poles on which arrow weeds were placed to make the shade. This shelter was open on all sides and was used in the summer time when the sun shines hot. There was always a large olla full of drinking water in the center of the vato. On a small rope stretched between the poles, strings of dried meat were hanging, or a small olla full of chu’i or pinole.

A double rope tied loosely and covered with a cotton cloth made a swing for the baby. Juana Losso often put little Keli•hi in this swing and as she swung the ropes back and forth she sang:

“Ululu ’ululu ’ululu’ u

My little baby is going to sleep,

For I am standing here swinging you,

As I am a little cricket,

As I am a little cricket.”

With the singing of this song, the baby soon went to sleep and Juana Losso was free to go about her work.

Beyond the vato was the olas-ki, or round-house, made of mesquite posts, willow and arrow weeds. This type of house is no longer used. It was enclosed all around, with a little dirt and straw on top to keep the rain out. The only opening was a small hole about two feet wide and four feet high which was used as a door. This door was always to the east. To get in, one had to get down on hands and knees.

You may wonder what the Pimas did for ventilation in such a house. That was very simple. The sides were covered with only arrow weeds. There was plenty of fresh air. Fire was seldom built in the olas-ki but in the winter a scoop-full of red hot coals was brought in and placed in the center on the dirt floor.

Around the four center posts, next to the wall there were sleeping mats made from yucca leaves. On these mats were home-made blankets woven from cotton. The Pimas grew their own cotton which they wove into cloth and blankets. The olas-ki was used only in rainy or cold weather. At all other times the open vato was the center of the home.

The Pimas are out-of-doors people and stay out in the open most of the time.

Up to the time I am remembering there had been no white people in our part of the country, except some Spanish explorers who passed through but never stayed. At this time though, the Pimas had heard of many white people over towards the east, but none had come out this far.

So the Pimas were enjoying a free and primitive life, living from day to day not knowing Sunday from any other day. But they knew their seasons and planted their crops accordingly and they prospered.

The Pima Indians have farmed along the Gila river for many, many years. Although we have no record, except the primitive Calendar Stick, it was told from one generation to the other that the Pima Indians have always lived along the Gila river.

The seeds were also handed down from generation to generation, and where they first got them, I do not know. They planted corn, a soft corn now known as Indian corn, and beans white and yellow, and squash, melons, wheat, tobacco and cotton. The tobacco they grew was called ban-viv...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- SOME PEOPLE MENTIONED IN THIS WRITING

- A PEACEFUL LIFE

- THE BATTLE OF AJI

- A RABBIT HUNT

- THE OLD WAYS

- THE FIRST WHITE MEN

- EARLY DAYS

- PIMA GAMES

- THE APACHE WARS

- PROGRESS

- THOSE WHO ARE GONE

- BOYHOOD

- SCHOOL DAYS

- THE GREAT WHEAT HARVEST

- FLOOD

- THE PIMA LANGUAGE

- HORSE ROUND-UP

- THE MISSION

- PIMA LEGENDS

- LEGEND OF THE HUHUGAM

- THE LEGEND OF HO’OK

- EAGLEMAN

- LEGEND OF THE GREAT FLOOD

- LEGEND OF THE BIG DROUGHT

- WHITE CLAY EATER

- THE LEGEND OF TODAY

- LAND

- WATER

- Flypaper

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Pima Remembers by George Webb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.