- 419 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

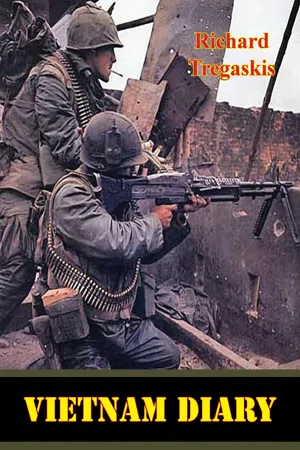

Vietnam Diary

About this book

"The first definitive eyewitness account of the combat in Vietnam, this unforgettable, vividly illustrated report records the story of the 14,000 Americans fighting in a new kind of war. Written by one of the most knowledgeable and experienced of America's war correspondents, Vietnam Diary shows how we developed new techniques for resisting wily guerrilla forces.

Roaming the whole of war-torn Vietnam, Tregaskis takes his readers on the tense U.S. missions—with the Marine helicopters and the Army HU1B's (Hueys); with the ground pounders on the embattled Delta area, the fiercest battlefield of Vietnam; then to the Special Forces, men chosen for the job of training Montagnard troops to resist Communists in the high jungles.

Mr. Tregaskis tells the stirring human story of American fighting men deeply committed to their jobs—the Captain who says: "You have to feel that it's a personal problem—that if they go under, we go under;" the wounded American advisor who deserted the hospital to rejoin his unit; the father of five killed on his first mission the day before Christmas; the advisor who wouldn't take leave because he loved his wife and feared he would go astray in Saigon. And the dramatic battle reports cover the massive efforts of the Vietnamese troops to whom the Americans are leaders and advisors.

An authority on the wars against communism is Asia, Tregaskis has reported extensively on the Chinese Civil War, Korea, the Guerrilla wars in Indochina, Malaya, and Indonesia. He was the winner of the George Polk Award in 1964 for reporting under hazardous conditions.-Print ed.

Roaming the whole of war-torn Vietnam, Tregaskis takes his readers on the tense U.S. missions—with the Marine helicopters and the Army HU1B's (Hueys); with the ground pounders on the embattled Delta area, the fiercest battlefield of Vietnam; then to the Special Forces, men chosen for the job of training Montagnard troops to resist Communists in the high jungles.

Mr. Tregaskis tells the stirring human story of American fighting men deeply committed to their jobs—the Captain who says: "You have to feel that it's a personal problem—that if they go under, we go under;" the wounded American advisor who deserted the hospital to rejoin his unit; the father of five killed on his first mission the day before Christmas; the advisor who wouldn't take leave because he loved his wife and feared he would go astray in Saigon. And the dramatic battle reports cover the massive efforts of the Vietnamese troops to whom the Americans are leaders and advisors.

An authority on the wars against communism is Asia, Tregaskis has reported extensively on the Chinese Civil War, Korea, the Guerrilla wars in Indochina, Malaya, and Indonesia. He was the winner of the George Polk Award in 1964 for reporting under hazardous conditions.-Print ed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Marines

Friday, October 12

Smith picked me up on time and by 7 A.M. we were threading our way through the assemblage of (former French) barracks buildings on the outskirts of Tan Son Nhut airfield. We found our way into an ancient French building as undistinguished and unfunctional as the MACV HQ, and checked with the well-worn American Air Force sergeant behind the desk. Soon we were rolling out onto the wide concrete plain of the airfield, picking our way along a line of dumpy C-123’s, wheelbarrow-shaped cargo planes carrying the white-star insignia of the U.S. We pulled up next to No. 287, the aircraft scheduled to go to Danang this morning, and I was surprised to see how big this kind of beast is: a bulbous giant that can lift 15 tons of freight on its two powerful turbo-prop engines. These C-123 Loadmasters, Smith told me, are the main supply link of our military support operations in Vietnam. Since the roads are primitive and considerable territory is not yet cleared of VC’s, we depend on these Air Force cargo planes, with an assist from some Army two-engine freighters called Caribous, to keep the far-flung fighting units supplied with all the impedimenta of modern war.

A bunch of crewmen in greasy fatigues were struggling to get a square crate into the open rear maw of the C-123. They were sweating and cussing in the oppressive early-morning heat of Saigon. A sturdy GI told us the aircraft would be taking off in 15 or 20 minutes. He was Airman First Class Jerry Morgan (of High Point, N.C.), serving as loadmaster on today’s flight.

One of the pilots, a slim lieutenant named Louis Kirchdorfer (of Roseborough, N.C.), superintended while about a dozen GI’s in fatigues and combat boots, with carbines and M-l’s, loaded their barracks bags among the crates of the plane’s cavernous interior. Most of them were Army Signal Corps people, heading for some secret assignment in Danang.

Lt. Kirchdorfer told me he has been here only a week, although his outfit, the Provisional Second Squadron of the 2d Air Division, Thirteenth Air Force, has been serving in Vietnam for almost five months. I asked him how he liked the life here.

“It’s fine if I can fly,” he said. “Otherwise, there’s nothing to do.” I asked what he does if he can’t fly on a certain day? What does he do to pass the time?

“Sleep,” he said.

It quickly developed that Kirchdorfer, like many another Air Force flier, is in love with flying—probably would be unhappy if he couldn’t fly, no matter what country he was stationed in. He’s a graduate aeronautical engineer from North Carolina State University—not a bad background for a co-pilot of a C-123 in Vietnam.

The other (first) pilot, Lt. Marshall L. Johnson (of Crestline, Calif.), is comparatively a veteran. He came in with the original bunch of pilots of the Second Squadron in June. Since that time, four of the stubby 123’s of the outfit have been hit by VC bullets, usually as they were dropping supplies by parachute to Vietnamese outposts surrounded by Communists. In early July, Johnson told me, one of the Second’s C-123’s plowed into a mountain near Ban Methuot to the north.

(Later I discovered that in that crash the pilot and co-pilot were injured. The two crewmen tried to get through the jungle to the nearest village, but soon got lost in the jungle thickets, then couldn’t even find their way back to the aircraft until the next day. Meanwhile, a patrol of VC’s reached the airplane, took what firearms they could find, but mysteriously didn’t bother the injured pilots. All four Americans were eventually rescued by Vietnamese government troops. Since that time the C-123 pilots and crewmen have always gone flying armed to the teeth.)

Lt. Johnson signaled us to board the aircraft, and we found places among the canvas seats along each side of the cargo compartment (arranged for maximum discomfort in true military fashion, with a bar of tube steel running down the middle of each seat space). We followed the Air Force requirement of putting on parachutes before take-off, fastened seat belts as ordered, and listened in stolid and sweaty misery while the plane’s navigator, Lt. Ed Rosane (of Pasco, Wash.), drilled us on the number of warning bells that would be sounded if we were to bail out, and what to do if we had a power failure on take-off: “Put your head between your knees because of flying glass.” We couldn’t have cared less about the possible danger of flying glass at that point.

At 8:20, with a great roar of engines, our ugly-duckling aircraft waddled toward the main long runway. The cabin looked like a bizarre junkyard, a storehouse of airplane parts with freight and passengers dumped willy-nilly inside: a cavernous tube of fuselage, with mazes of wiring, tubing, ducts, metal sheets, and rivets exposed everywhere, and the freight—cargo crates, tanks, huge containers of rations, spare airplane parts—dumped in with the passengers.

The plane reached the end of the runway, swung around, and lurched to a stop. We sat there waiting, sweating in harnesses and being gored by the tubing seats. I couldn’t see out the windows as we took off, because the canvas seats put our backs against what windows there were. Never mind, I had one fair idea about traveling around Vietnam: It was going to be uncomfortable.

The crewmen adjusted to the discomforts of C-123 flight as if they had been through plenty of it. They hopped nimbly over the pile of cargo at the center of the fuselage and sacked out on various flat spaces as the plane gained altitude. Loadmaster Jerry Morgan had corralled a Medical Corps stretcher for sack-out purposes and, with a spare parachute for a pillow, extracted a pocketbook, The Roots of Fury, by Irving Shulman, from his pocket, lit a cigarette, and relaxed.

The Signal Corps GI next to me was an angular PFC named David Weiss (of Omro, Wis. ), attached to the hush-hush radio communications outfit going up to Danang: “We’re a little bit on the agency side ... We don’t talk very much about it.”

Next to him was Sgt. Charles Parnell (of Lamperton, N.C.), a rugged-looking (battered nose, cauliflower ear) mechanic attached to the C-123 outfit, the Second Provisional Squadron. He was going to be dropped off at Quang Ngai, en route to Danang, to work on a C-123 stranded on that exposed landing strip in VC-dominated territory.

I had borrowed Lt. Rosane’s headphones so that Johnson could talk to me by interphone despite the ear-dinning sound of those loud engines. He told me as we droned northward that this was going to be an “assault-type landing,” meaning that because the landing strip at Quang Ngai is very short, emergency procedures for coming into such a cramped area have to be followed.

“The approach is a little lower ... 60-degree flaps instead of 45 ... reverse power ... can come to a stop in 600 feet with 47-48 thousand pounds gross weight,” he explained.

It was a typical rainy day in Vietnam, with very few breaks in the floor of cumulus clouds below us. At 10:20, I figured we were just about above Quang Ngai, because I heard co-pilot Kirchdorfer suggest, “How about going through that hunk of blue?”

Johnson, like the experienced senior pilot he is, said, “I’ll go out to the coot and come back under it (the cloud cover). It’ll only be a couple of minutes.” I guessed he was thinking that messing around in the clouds with all those mountains around can be rapidly fatal, as it has been for many pilots here.

“A bush war is going on right now,” Johnson said as we came into Quang Ngai. “Two helicopters got shot down out there, about 20 miles west, about five weeks ago.”

When the ramp opened and the dust settled, I could see the clumsy silver shape of another C-123 nearby. That would be the aircraft that Sgt. Morgan was going to repair.

A jeep came dashing toward us, with three Air Force men draped on it, all armed with pistols, bandoleers of ammunition, and sheath knives. Inside the plane, the sturdy Sgt. Parnell hurried to untie a squarish, yellow-painted metal stand from its cargo straps. Jerry Morgan sprang into fast action to help free the equipment, with an assist from a third crew member, husky, black-skinned Sgt. Willie Washington of Tallahassee, Fla. The gadget they were wrestling with was a starter motor for the downed C-123. If Parnell did a good job of installing that motor, the C-123 would be airborne and droning south to Saigon before sundown today, rescued from another precarious night in this narrow strip of outpost-airfield. It seemed evident from the general haste that this little strip was frequently under VC sniper fire and the unloading job had to be done quickly so that the second C-123 could get away before it, too, became disabled. You could see this urgency in every move of the men wrestling with the heavy aircraft equipment.

Nor could you miss the urgency with which Lt. Johnson gunned his engines as soon as the equipment was out, and shut the ramp doors as we taxied away. We speedily reached take-off position, wheeled around, and were off with a jerky blast of power, still sweating and wiping the dust out of our eyes.

I went forward to join the pilots as we flew along the seacoast under clear skies, riding over miles of handsome yellow sand beaches, deserted except for occasional clusters of houses and concentrations of fishermen’s sampans shaped generally like the dories of New England. Most of the fishing boats were drawn up on the sand among the scrub trees of the beach front. A few were offshore, bobbing on the lucent aquamarine water. Where there were towns, there were also, invariably, large blanched squares of land, salt evaporating basins. Salt is great trading material in this part of the world.

Soon we were over a wide, sweeping bay and inland, a far-sweeping grid of houses and a few gray ribbons of surfaced roads: Danang. It had been a French naval base and resort town in Indochina days, when it was called Tourane.

We turned and moved up a widespread river valley and came out over a large airdrome. I went back to my seat again for the landing. We jerked to a stop on the Air Force side of the base, the ramp opened, and we passengers filed down the open ramp toward old French hangars beyond a plain of Marston mat—World War II pierced-steel planking. No doubt we had arrived too late to get any lunch today: Military flights seem invariably to be set up this way for passengers. But at least we had reached Danang.

I hitched a ride with an Army major to the Marine side of the airport. Also housed in the old French hangars and nickel-sized offices, which might be right for the French or the Vietnamese, the Marine headquarters seemed too small for Americans. In a lean-to office beside the hangar I met a lieutenant colonel whose name struck sympathetic memory chords. He was Don Foss, a cousin of a famed Marine flier I had known in Guadalcanal days, Capt. Joe Foss, who got the Congressional Medal of Honor for leading the Marine fighter planes defending Guadalcanal. Later, Joe Foss became governor of his state, South Dakota, and after that, commissioner of the American Football League.

Don Foss came from the same area, Sioux Falls, S.D., and somehow he looks like Joe—large and plain—although this Foss has followed a different branch of service within the Marine Corps. He’s attached to a helicopter outfit and spends most of his flying time at the controls of the little observation and reconnaissance planes (called “L-19” in Army language, or “OE” in Marine-Navy talk) that do the scouting for the whirlybirds.

Foss drove me across the runway and over a wide expanse of meadows, through a little Vietnamese colony of former plantation houses and jerry-built shops for such tradesmen as grocers, tailors, bicycle dealers.

We turned into a big military compound behind barbed-wire barriers, where long barracks-type buildings of rough concede were ranged. We pulled up in front of one and Foss helped me unload my gear.

Inside the building, there was a long hall, with cubicles on both sides, and a large bathroom, with a row of showers and a tile floor that has a huge “93” embedded in it. Foss explained that the bathroom had been built by the 93d Transportation (Army) Company, which had previously occupied the building. Then the 163d Marine Squadron came in and switched places with the 93d, which went to Soctrang, south of Saigon, where the Marines had been flying since arriving in Vietnam.

The change was a wise one, Foss said, because the Marine helicopters, the HUS’s, have more power and can maneuver better in the highlands and mountains. The Army H-21’s, which take longer to climb and can’t carry as much load, are OK for air-phibious assaults in the flat Delta terrain.

The Marines have taken hold of the challenge both in the Delta and up here, Foss said. “They have proved this stuff from one end of the country to the other.... They are professional helicopter people.

“Troops would never have gotten in, down in the Delta or up here in the mountains, without them. The helicopters proved their worth ... the troops back us up on this.”

In the barracks, we met Maj. Aquilla “Razor” Blaydes (of Dallas, Tex.), a dark, saturnine man who is the operations officer of this Marine squadron.

“Have you got a flight out now?” Foss asked him, for my edification. “I’ve got several.”

“How many?”

“Fourteen.”

I asked what the flights were and Blaydes answered:

“Administrative (carrying people around), resupply (carting food, ammunition, supplies), and an emerge...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Arrival

- The Marines

- The Army

- A Leave in Hong Kong

- D-Zone

- Junk Fleet

- D-Zone

- The Swamps of Soctrang

- The Special Forces and Strategic Hamlets

- Christmas, a Battle, a Free Election

- ILLUSTRATIONS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vietnam Diary by Richard Tregaskis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.