eBook - ePub

Napoleon: a History of the Art of War Vol. III

from the Beginning of the French Revolution to the End of the 18th Century [Ill. Edition]

- 510 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Napoleon: a History of the Art of War Vol. III

from the Beginning of the French Revolution to the End of the 18th Century [Ill. Edition]

About this book

Includes over 200 maps, plans, diagrams and uniform prints

Lt.-Col. Theodore Ayrault Dodge was a soldier of long and bloody experience, having served with the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War losing one of his legs during the battle of Gettysburg. After the end of the war he settled down in retirement to write, he produced a number of excellent works on the recently ended Civil War and his magnum opus "A History of the Art of War", tracing the advances, changes and major engagements of Western Europe. His work was split into twelve volumes, richly illustrated with cuts of uniforms, portraits and maps, each focussing on periods of history headed by the most prominent military figure; Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Frederick the Great and finally Napoleon. Napoleon and the period which he dominated received such care and attention that Dodge wrote four excellent, authoritative and detailed volumes on him.

This third volume begins with Napoleon's ambitious foray in Spain and Portugal in 1807-8, despite British intervention his forces are triumphant over much of Spain. Napoleon is forced to turn back to his Eastern enemies as Austria attack on the Danube, even Napoleon's great powers cannot gain him victories at all times and his repulse at Aspern hands him his first major defeat. He is able to bring the Austrians to heel after the bloody battle of Wagram, but his over vaulting ambition is beginning to become too much; as reverses in the Peninsula mount he decides on the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. This volume concludes as the remnants of the Grande Armée trudge back through the snows of Russia and his lieutenants are roundly beaten by Wellington at Vittoria.

A well written, expansive and excellent classic.

Lt.-Col. Theodore Ayrault Dodge was a soldier of long and bloody experience, having served with the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War losing one of his legs during the battle of Gettysburg. After the end of the war he settled down in retirement to write, he produced a number of excellent works on the recently ended Civil War and his magnum opus "A History of the Art of War", tracing the advances, changes and major engagements of Western Europe. His work was split into twelve volumes, richly illustrated with cuts of uniforms, portraits and maps, each focussing on periods of history headed by the most prominent military figure; Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Frederick the Great and finally Napoleon. Napoleon and the period which he dominated received such care and attention that Dodge wrote four excellent, authoritative and detailed volumes on him.

This third volume begins with Napoleon's ambitious foray in Spain and Portugal in 1807-8, despite British intervention his forces are triumphant over much of Spain. Napoleon is forced to turn back to his Eastern enemies as Austria attack on the Danube, even Napoleon's great powers cannot gain him victories at all times and his repulse at Aspern hands him his first major defeat. He is able to bring the Austrians to heel after the bloody battle of Wagram, but his over vaulting ambition is beginning to become too much; as reverses in the Peninsula mount he decides on the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. This volume concludes as the remnants of the Grande Armée trudge back through the snows of Russia and his lieutenants are roundly beaten by Wellington at Vittoria.

A well written, expansive and excellent classic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Napoleon: a History of the Art of War Vol. III by Lt.-Col. Theodore Ayrault Dodge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

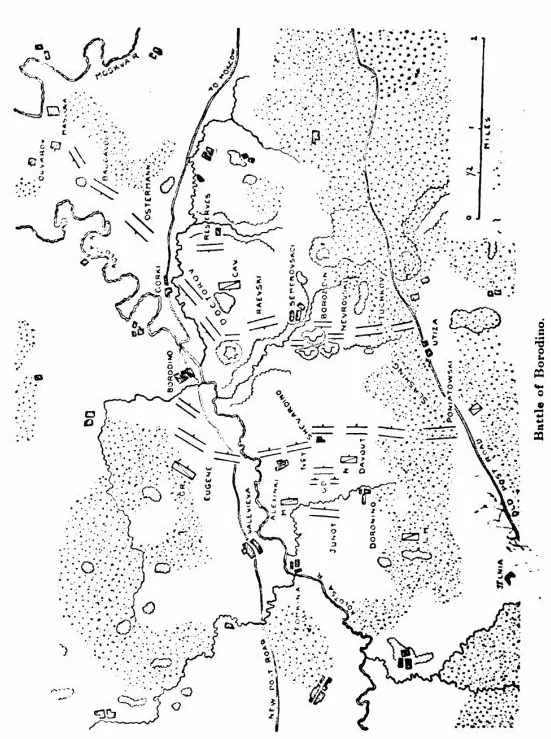

LII. — BORODINO. SEPTEMBER 1 TO 7, 1812.

WHEN the army reached Gshask September 1, within eight days of Moscow, it seemed natural to keep on, though the Grand Army was almost a wreck and the rear looked doubtful. Barclay was superseded by Kutusov, who stayed at Borodino to fight. Napoleon reached his front September 4, and prepared for a decisive struggle. The Russian army stood across the Moscow roads behind a brook and the Kolotsa River, with one big and three small redoubts in its front. Napoleon would not try too marked a turning manœuvre lest it should again retreat, but prepared to break down its centre. There was a vast array of guns; Kutusov had one hundred and twenty thousand men, Barclay on the right, Bagration on the left; Napoleon somewhat less, with Eugene on the left, Davout, Ney and Murat in the centre, and Poniatowski on the right. The Russians were well fed, the French had scant rations. Napoleon opened the battle early September 7 with the guns, and by advancing the centre to take the redoubts, and Eugene to capture Borodino and the big fort, while Poniatowski was to turn the Russian left. The first assault failed, but later the redoubts were taken, Eugene captured Borodino, and Poniatowski advanced slowly. The Russians retired somewhat, and Ney, feeling sure he could drive them into rout, called for reinforcements. But at this moment a Cossack attack on Eugene’s left arrested the emperor’s attention, and he delayed sending Ney help. The Cossack attack proved trivial, but an hour had been lost. The infantry fighting died down, but into the heavy masses on either side eight hundred guns poured constant fire. Eugene by a final effort captured the big fort, and this was the end of the battle. The Russians had used every man; Napoleon still had the Guard. He believed the Russians must have reserves, and declined to put the Guard in. Had he done so, we know to-day that he would have destroyed the Russian army. As it was, the French had not won the decisive victory needed. They had lost thirty thousand men, the Russians probably forty thousand, but Kutusov’s army retired during the night in fairly good order, and the French bivouacked on the battlefield. Borodino was a battle fought in parallel order all along the line without grand-tactics. In it the French army showed wonderful gallantry, and the Russians equal devotion. The percentage of losses was, for such large bodies, the greatest of modern times. Otherwise the battle had no unusual features.

ARRIVED at Gshask September 1, within eight days’ march of the sacred city of Moscow, the ancient capital of Russia, which was full of food and material and a fit resting-place for the foot-weary troops, and especially when the Russians again speeded their retreat, it seemed to Napoleon more natural to proceed. Having sent orders to Victor to come on to Vitebsk or Smolensk with his corps, and to Augereau to bring half his force to Königsberg and Warsaw, to protect his line of advance, the emperor confidently set out to follow the Russian forces. If he had any misgivings, we are not permitted to know them.

The rear of the Grand Army was ill cared for. As a general rule, orders given by the emperor were supposed to be executed apart from any difficulties in the way, but he was now too far distant to know the facts or punish laxity or dishonesty. The able administrators could not, and the lazy ones would not, carry out instructions; and many an employee, divining the future, lined his own pocket. Repairs on bridges and roads were neglected, and the collection of victual was so ill attended to, that the convalescents following the army had issued to them only half-rations. Habituated to exact obedience, few officers dared act on their own initiative, and the well-provided line of communications it was Napoleon’s purpose to create became a road of starvation, because the impossible was ordered and the possible was not done. Napoleon had also found out that his staff was ill-trained. He had written Berthier, July 2, that “the general staff is organized in a fashion that one can see nothing ahead by its means,” and now, on September 2, he wrote: “My Cousin, the general staff is of no use to me. Neither the grand provost of the gendarmes, nor the wagon-master, nor the staff officers, not one of them serves as he ought to do.” But he none the less made skillful preparations for what was in his front, believing he should yet win a decisive battle, and that this would cure the difficulties in his rear, which he was keen enough to suspect, at least in part, but practically never mentioned.

Meanwhile, battle never left the emperor’s mind. On August 30 he wrote Berthier: “Give orders to General Eblé to leave at five o’clock in the morning to rejoin the vanguard. He will have all the bridges in the rear repaired. He will march with all his personnel,” and all his tools, but no pontoons. “You will make this general understand that as we are nearly in the presence of the enemy, and as it is probable that in three or four marches there will be a general battle, success may depend on the rapidity with which are established the debouches, and the bridges over the torrents and the ravines. That it is indispensable for him to be there, so that, as soon as shall be possible, he may construct these debouches. For an army like this one, there are needed always at least six. For this purpose he is to work with the engineers, and not await any new order to see to the erection of bridges over the ravines and little streams.” Chasseloup was also given similar orders to cooperate with Eblé. And then, as he had been riding with the van, he added: “Let me know where is to be found the 4 Little Headquarters,’ of what it consists, and when it can leave.” Next day he wrote Berthier “to have the caissons which are empty loaded with brandy, to be used on a day of battle;” and on September 1, to Maret: “It is probable that in a few days I shall have a battle. If the enemy loses it, he will lose Moscow. My communications from Vilna to Smolensk are not difficult, but from Smolensk here they may become so. We need more troops, some national guards. They need not be good, because they are opposed only to peasants.”

Grave abuses had grown up under the trying conditions of the march. One has only to read between the lines of the following Order (of which only the substance can be given) to see how much there was to cure. In effect, the abuses did not, could not, get cured; scarcely palliated.

ORDER OF THE DAY.

GSHASK, September 1, 1812.

“His Majesty the Emperor and King has ordered as follows: “1st. All wagons to move after the artillery and the ambulances. 2d. Private wagons found in the way of the artillery or ambulances to be burned. 3d. Only the artillery wagons and ambulances to follow the vanguard; other wagons to be two leagues in the rear, and any such found nearer to be burned. 4th. At the end of the day no wagons to rejoin the vanguard until after it has taken position, and fighting has ceased; any wagons transgressing this rule to be burned. 5th. In the morning such wagons to be parked outside the road; those found on the road to be burned. 6th. These dispositions to apply to the whole army. 7th. The chiefs of staff of each division and corps to see that the baggage wagons march in the rear and separate, and in command of a good wagon-master. 8th. General Belliard, chief of staff of the vanguard, to see that these orders are obeyed at the vanguard, and that the wagons do not pass the defiles without his knowledge. 9th. This order to be read September 2 to all the corps, and “His Majesty gives notice that on September 3 he will see himself to the burning in his presence of the wagons found in contravention of this order.” But next day he wrote Berthier: “See to it that the first baggage wagons that I order burned shall not be those of the general staff. If you have no wagon-master, name one and let all the” (staff) “baggage march under his directions. It is impossible to see a worse order than now reigns.”

Davout came in again for his share of scolding. On September 2 Napoleon wrote:—

“My Cousin, I was ill satisfied yesterday with the manner your corps was marching. All your companies of sappers, instead of mending the bridges and the debouches, did nothing, excepting those of Compans’ division. No direction had been given to the troops and the baggage to pass the defile, so that all found themselves on one another’s heels. Finally, instead of being a league behind the vanguard, you were close upon it. All the baggage wagons, etc., were in front of your corps, in front even of the vanguard, so that your wagons were in the town before the light cavalry had debouched. Take measures to remedy such a bad condition, which might seriously compromise all the army.” And on the same day, to Berthier: “My Cousin, for two days I have not seen a report of the position of Davout. I do not know where his corps is. Let me understand why this is. It is his duty to make a report every day.”

Inasmuch as Davout was always noted as a strict disciplinarian, we may assume that equal criticism was applicable to the other corps.

From the enemy’s signs of readiness to defend the road to Moscow the emperor now guessed that the long anticipated battle would within a few days be delivered, and he began his preparations. At Gshask, September 2, he wrote Berthier to give orders to Murat, Davout, Eugene, Poniatowski and Ney to repose and rally the troops, “to have roll-call at three o’clock in the afternoon, and to let him know positively the number of men who will be present in the battle; to have an inspection made of arms, cartridges, artillery and ambulances; to make the soldiers understand that we are approaching the moment of a general battle, and that they are to prepare for it.” He demands, by ten o’clock in the evening, a statement of the number of troops, of guns, their calibre, the rounds they have, the number of cartridges per man, the number in the caissons, the state of the ambulances, the number of surgeons and their material. Also the detached men who are not present, who will not be present the next day, but who can be up in two or three days, the number of horses without shoes, and the time necessary to shoe them. “These reports are to be made with the greatest attention, because on their result will depend my resolve.” Murat, Poniatowski and Eugene were to advance slightly and rectify their position. The Russian nation, or at least the nobles, for the serfs had no part in the matter, had undertaken the campaign with great enthusiasm, especially in the Moscow district, where ten per cent, of the male population was allotted to the field. The nobles did not understand the wisdom of retreat: invariably assured that the Russian armies were successful, they asked why such constant retreat, and who was at fault? The blame was cast upon Barclay, who was not of Russian blood; and Kutusov, the victor of Rudshuk, became the hero of the nation. Despite his autocratic power, the czar had assembled a commission to select a new commander, and Kutusov proved to be the choice. The Chancellor, Rumantzov, who had been in favor of the French alliance, was also suspected of playing into the enemy’s hands; and Sir Robert Wilson, the English envoy, conveyed to the czar, from the army officers in St. Petersburg, what was really a mutinous message, based on the fear that Rumantzov might make peace. Alexander received the message sensibly, and assured Wilson that “he would sooner let his beard grow to the waist, and eat potatoes in Siberia, than permit any negotiations with Napoleon so long as an armed Frenchman remained in the territories of Russia.” As to the suspicion expressed, the czar not only retained his confidence in Rumantzov, but he would not submit to dictation: his course at this time shows him to have had unusual balance.

We remember Kutusov in the Austerlitz campaign. He was a good average soldier, perhaps no better than Barclay. He was now seventy, too portly to ride, and not active. Although he had failed in 1805, he yet represented the fighting quality of Suwarrov, and having won the peace in Turkey, he was trusted. Had Barclay fought at Dorogobush, or at Gshask, the nation would have demanded a brilliant victory; but when Kutusov withdrew from Borodino, it was felt that the best possible had been done,—as indeed was true. Had any soldier weighed the conditions at Gshask, as present facts enable one to do, he might have predicted just what happened: the French must march to Moscow; there must be a battle to dispute their advance; and once in Moscow, they could not hold themselves. The advance beyond Smolensk had been a fatal error.

That Kutusov would not fight in Barclay’s chosen position, because he might lose part of the credit of a victory, is less probable than that he delayed battle so as to get acquainted with the army. As Clausewitz says, one position was about as good as another. On an open plain, hundreds of miles wide, without marked hills, no stone-built villages to act as redoubts, and few unfordable streams, any position might be turned, and no enemy would attack earthworks if he could turn them. Had not Napoleon ardently longed for a pitched battle, he never would have attacked at Borodino. The new commander had orders to fight the battle which the czar and the nation demanded for the safety of Moscow; and not deeming the position of Zarevo-Saimichi a good one, he had fallen back August 31, on which day Napoleon and the French van reached Vilichevo, with Junot at Viasma, Eugene on the left at Pokrov, and Poniatowski on the right at Sloboda. On September 1 and 2 Kutusov continued his retreat towards Mozhaisk, and on the 3d reached the chosen place on the heights back of the Kolotsa, opposite Borodino. Here he stopped, resolved to receive a battle.

At Gshask, September 1, news of Kutusov’s appointment fully convinced Napoleon that the Russians would fight, and here he concentrated the arriving corps, so as to advance well massed. Murat marched through Gshask, and took position, September 2, a few miles beyond; Davout and Ney remained nearby the town, Eugene at Pavlovo, and Poniatowski in the Sloboda country, Junot still being back at Tieplucha.

At Gshask, September 3, another attempt was made to stop the evil of straggling, and Berthier was instructed to write to the corps commanders that “many men are lost by the disorder in which foraging is done; that they must arrange measures to put a term to a set of things which menaces the army with destruction; that the number of prisoners which the enemy makes mounts every day to several hundred; that under the severest penalties soldiers must be forbidden to straggle.”

The reports called for by the order of the 2d showed one hundred and twenty-eight thousand men in line, with six thousand more to arrive within five days; and during September 3 Junot came up. It had been raining for three days, but on September 4 it cleared, and the army moved under pleasant skies forward from Gshask toward the fateful field of Borodino. By afternoon Murat, at Gridnieva, ran into the Russian rearguard, which after a defense until nightfall retired to Kolotsi. Personally, Napoleon was at the front, bivouacking at Gridnieva. Next day Murat again attacked the Russian rearguard at Kolotsi, while Eugene turned their flank at Lusosi, and the body fell back on the main army at Borodino, which Murat drew near by 2 P. M., Eugene advancing by way of Bolshi Sadi and Poniatowski by way of Jelnia.

Two post-roads ran from Smolensk to Moscow, an old one and a new. The village of Borodino lay on the new road, where it crossed the Kolotsa, an affluent of the Moskwa; the old one being here two miles and a half to the south. The country is rolling rather than strongly accentuated, but the many brooks run in ravines more or less deep. The country was full of woods, and where these had been cut down were left what we call slashings, alternating with open fields. For a couple of miles the Kolotsa, fordable in places, but needing bridges for quick passage, meanders along parallel to and south of the new road, until near Borodino it crosses and leaves it to flow northerly towards the Moskwa; and just above Borodino a little brook runs from the south in a marked ravine, and falls into it. East of the brook, the land rises into a plateau a mile wide; then comes another ravine and another plateau. Near the head of this brook, a mile southerly from Borodino, lay the village of Semenovskoi, on a sloping hill with the brook in its front. It had been razed, for a wooden village, easily set afire, is more of a danger in the line of battle than a defense. On the west side of the brook-ravine are three hillocks, each of which had been crowned by a simple arrowhead field-work, open in the rear a redan. Between Semenovskoi and Borodino was a hill crowned by a good bastioned redoubt, and in front of all these works the slope was gentle and favorable to artillery fire. Several small works covered the right wing. On the old road, due south of Borodino, is the village of Utiza. North of Borodino lies fairly open country, and between the two roads are a number of hamlets and villages. The position was liable to be turned; but it was also one easy to defend, for in its front assaulting troops could not manœuvre and preserve their formation, and a column forcing its way forward in a ragged mass would be apt to be decimated by well-placed guns.

After a reconnoissance Napoleon first ordered the capture of the intrenched villages of Fomkina, Alexinki, Doronino and Shivardino, which would threaten the French right as the columns marched along the new post-road. Fomkina was easily taken by Murat, who there crossed the Kolotsa, followed by Davout; and while both took Alexinki and deployed in front of the Russian centre, Poniatowski debouched from Jelnia, captured Doronino and threatened the enemy’s left flank. Shivardino was valiantly defended, and when lost, retaken; but by 10 P.M. this position also was yielded to Com pans, the Russians falling back on their line of battle. For the night Napoleon’s bivouac was near Valevieva on the new road, the Guard with Eugene’s corps in its front. Ney came up in Davout’s rear; Junot still lay at Gshask. With battle to face, the emperor took short rest. By 2 A. M. he was in the saddle, and with Caulaincourt and Rapp set out to reconnoitre the Russian position.

Kutusov probably had one hundred and twenty thousand men in line, of whom seventeen thousand were irregulars and militia, wherewith to meet Napoleon’s somewhat less number. He had leaned his right on the Moskwa near Maslova, whence the line ran behind the Kolotsa to Gorki, and the left wing stretched out through Semenovskoi to Utiza. The line was slightly convex, and troops could be easily moved to and fro back of the Russian front. That the left wing was not protected by the Kolotsa and might be turned from Jelnia, was the origin of the field-works erected; but the sandy soil did not pack well and time had been short; and Kutusov knew that impregnable works would be turned and not assaulted.

Barclay was in general command in the right wing from the big redoubt to the Moskwa, his line being broken by a ravine at Gorki. Bagration commanded the left wing, from the big redoubt to a large wood slashing between Semenovskoi and Utiza. Baggavut, with Ostermann on his left, lay north of the new road, with Ouvarov’s Cossacks out on the right as far as the Moskwa; Doctorov extended from the new road to the great redoubt, which he was chosen to protect; Raevski stood on his left to Semenovsko...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE.

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- XXXVIII. - MEDINA AND BAYLEN, OCTOBER, 1807, TO JULY, 1808.

- XXXIX. - SIR ARTHUR WELLESLEY. JULY TO SEPTEMBER, 1808.

- XL. - NAPOLEON IN SPAIN. OCTOBER, 1808, TO JANUARY, 1809.

- XLI. - RATISBON. FEBRUARY TO APRIL, 1809.

- XLII - ABENSBERG AND EGGMÜHL. APRIL 19 TO 23, 1809.

- XLIII - AGAIN TO VIENNA. APRIL TO MAY, 1809.

- XLIV. - ESSLING OR ASPERN. MAY 21-22, 1809.

- XLV. - THE ISLAND OF LOBAU. MAY 23 TO JULY 5 1988

- XLVI - WAGRAM AND ZNAIM. JULY TO NOVEMBER, 1809.

- XLVII. - OPORTO AND TALAVERA. 1809.

- XLVIII. - BUSACO, FUENTES, ALBUERA, BADAJOZ. 1810-11.

- XILX. - THE INVASION OF RUSSIA. 1811 TO JUNE. 1812

- L. - VILNA TO VITEBSK. JULY, 1812.

- LI. - SMOLENSK AND VALUTINO. AUGUST, 1812.

- LII. - BORODINO. SEPTEMBER 1 TO 7, 1812.

- LIII. - MOSCOW. SEPTEMBER 8 TO OCTOBER 19. 1812

- LIV. - MALOYAROSLAVEZ. OCTOBER 19 TO NOVEMBER 14, 1812.

- LV. - THE BERESINA. NOVEMBER 15, 1812, TO JANUARY 31, 1813.

- LVI. - SALAMANCA AND VITTORIA. 1812-1813.

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER