- 495 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wedemeyer Reports!

About this book

As the chief planner for General Marshall, and co-author of the Victory Plan, General Wedemeyer had a truly significant hand in shaping and directing the Allied War effort against the Fascist powers. In these brilliant, excellently written memoirs he reveals the planning and execution of Grand Strategy on a global scale that toppled Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo.

""The Second World War," says historian Walter Millis, "was administered."...As a war planner in Washington from 1940 into 1943 I was intimately involved in an attempt to see the war whole—and even after I had moved on to Asia, where I served successively on Lord Louis Mountbatten's staff in India and as U.S. commander in the China Theater, I was still close to the problems of adapting Grand Strategy to a conflict of global dimensions.

It was inevitable, then, that the subject of Grand Strategy should predominate in this book. I was not deprived of my own share of war experience from close up, but my most strenuous battles were those of the mind—of trying, as we in Washington's planning echelons saw it, to establish a correct and meaningful Grand Strategy which would have resulted in a fruitful peace and a decent post-war world.

There were many obstacles in the way of developing a meaningful strategy, of assuring that our abundant means, material and spiritual, would be used to achieve worthy human ends. First, there was the pervasive influence of the Communists, who had their own plans for utilizing the war as a springboard to world domination. Second, there was the obstinacy of that grand old man, Winston Churchill, who, as we soldiers felt, could never reconcile his own concepts of Grand Strategy with sound military decisions. Because we had to contend with the machinations of Stalin on the one hand and with the bulldog tenacity of Churchill on the other, this book has had to be harsh in some of its personal assessments."-Foreword

""The Second World War," says historian Walter Millis, "was administered."...As a war planner in Washington from 1940 into 1943 I was intimately involved in an attempt to see the war whole—and even after I had moved on to Asia, where I served successively on Lord Louis Mountbatten's staff in India and as U.S. commander in the China Theater, I was still close to the problems of adapting Grand Strategy to a conflict of global dimensions.

It was inevitable, then, that the subject of Grand Strategy should predominate in this book. I was not deprived of my own share of war experience from close up, but my most strenuous battles were those of the mind—of trying, as we in Washington's planning echelons saw it, to establish a correct and meaningful Grand Strategy which would have resulted in a fruitful peace and a decent post-war world.

There were many obstacles in the way of developing a meaningful strategy, of assuring that our abundant means, material and spiritual, would be used to achieve worthy human ends. First, there was the pervasive influence of the Communists, who had their own plans for utilizing the war as a springboard to world domination. Second, there was the obstinacy of that grand old man, Winston Churchill, who, as we soldiers felt, could never reconcile his own concepts of Grand Strategy with sound military decisions. Because we had to contend with the machinations of Stalin on the one hand and with the bulldog tenacity of Churchill on the other, this book has had to be harsh in some of its personal assessments."-Foreword

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

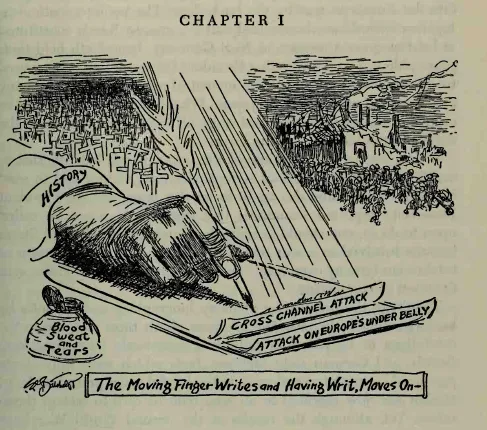

CHAPTER I – PRELUDE TO WAR

PEARL HARBOR brought an abrupt and inconclusive end to the Great Debate between the interventionists and the isolationists. There could no longer be any question whether to fight or not to fight, once America had been attacked. We were now, willy-nilly, engaged in combat in the Pacific, and Germany, by declaring war on us in support of her Japanese ally, shut off any opposition to our intervention in the European struggle. The America Firsters henceforth joined in the war effort as ardently as the Britain Firsters and the Russia Firsters. The fact that Japans attack had been deliberately provoked was obscured by the disaster at Pearl Harbor and by the subsequent loss of the Philippines, where the American garrison was regarded as expendable by an Administration bent on getting us into the European war by the back door. The noninterventionists, together with those who realized that Communist Russia constituted at least as great a menace as Nazi Germany, henceforth held their peace although well aware that President Roosevelt had maneuvered us into the war by his patently unneutral actions against Germany and the final ultimatum to Japan. Whatever one’s views on the origins of the war, we now had to go all out to win, and leave the debate to the historians of the future.

Today, seeing the wreckage of the hopes which led America to mobilize her great industrial strength for total victory and to send her sons to fight and die again in foreign wars, despite President Roosevelt’s repeated assurances that they would never be called upon to do so, one should examine how and why the United States became involved in a war which was to result in the extension of totalitarian tyranny over vaster regions of the world than Hitler ever dreamed of conquering.

Thanks to the publication of many biographies and memoirs by leading actors in the most tragic drama of our time, and also to the revelations to be found in published documents from American, British, and German state archives, facts which were only dimly perceived by noninterventionists in the fateful years preceding Pearl Harbor are now revealed to all who read or care to inform themselves. Yet, although the results of the Second World War have proven far more harmful to our security, there has as yet been no era of “debunking” such as followed the 1914-18 war. In the twenties, the public on both sides of the Atlantic was disillusioned concerning the origins, causes, and consequences of that conflict by a flood of books, articles, and speeches exposing the facts which contradicted wartime propaganda. Within less than a decade the myth of sole German “war guilt” had been shattered, the real causes of the war uncovered, and the evil consequences of the punitive Versailles Peace Treaty recognized. But today, many years after the fighting ended only to be succeeded by the cold war with our former “gallant ally,” the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, there has been no comparable probing into the real causes of the war or general recognition that the present perilous world situation is largely of our own making.

Few will even admit that the Soviet colossus would not now bestride nearly half the world had the United States kept out of the war, at least until Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany had exhausted each other. If we had followed the policy advocated by ex-President Hoover, Senator Taft, and other patriotic Americans, we probably would have stood aside until our intervention could enforce a just, and therefore enduring, peace instead of giving unconditional aid to Communist Russia. And if, after we became involved in the war, Roosevelt and Churchill had not sought to obliterate Germany, which was tantamount to destroying power equilibrium on the Continent, we might not have fought in vain.

Our objective should have been maintenance of the Monroe Doctrine and the restoration of a balance of power in Europe and the Far East. The same holds true for England, whose national interest, far from requiring the annihilation of her temporary enemies, was irretrievably injured by a “victory” which immensely enhanced Soviet Russian territory, power, and influence. It is indeed one of the great ironies of history that Winston Churchill, who had proclaimed that he had not become the King’s First Minister “in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire,” pursued policies which hastened Britain’s decline to her present status of a second-rate power. In none of his books has he ever recognized either his own or Roosevelt’s responsibility for the disastrous outcome of the war. Yet in the preface to his history of the Second World War he writes:

“The human tragedy reaches its climax in the fact that after all the exertions and sacrifices of hundreds of millions of people and of the victories of the Righteous Cause, we have still not found Peace or Security, and that we lie in the grip of even worse perils than those we have surmounted. [Italics added.]”

Churchill indeed seems to lack either the wisdom to recognize his mistakes or the greatness to admit them and say mea culpa.

It is indeed strange that Churchill, who belonged by birth and tradition to the long line of British statesmen who had made England the greatest power in the world by intelligent strategy in peace and war, reveals himself as lacking their wisdom and statecraft. Instead of seeking to re-establish the balance of power in Europe, which had been the constant objective of British policy for more than three hundred years, he sought the destruction of Germany and thus gave Russia an opportunity to dominate Europe. Churchill’s folly in disregarding the precepts of his forebears and letting his passions sublimate his reason was matched by Roosevelt’s disregard of George Washington’s advice to his successors in the conduct of United States policy. In his “Farewell Address,” Washington said:

“In the execution of such a plan, nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded; and that, in place of them, just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation which indulges towards another an habitual hatred or an habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. . . . The peace often . . . of Nations has been the victim.”

“. . . Sympathy for the favorite Nations, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter, without adequate inducement or justification. . . .”

This and other wise precepts of the Founding Fathers of the Republic which have stood the test of time were ignored by Roosevelt who, like the dictator he so passionately hated, directed U.S. policy on the personal level and imagined that Stalin was, or could be induced to become, “his friend,” and Soviet Russia a permanent ally.

There is little doubt that a majority of the American people, remembering the broken promises of the 1914 war, desired to keep out of the Second World War which they instinctively, or by reason of past experience, realized could not lead to any better results and might well prove more disastrous. It was made clear both by Roosevelt’s campaign promises and by the support given to Charles Lindbergh and others who forewarned of the disastrous consequences which would ensue from their engagement in yet another “Crusade” that they wanted to follow George Washington’s too often neglected advice.

A generation born or brought up in the debunking era of the twenties and thirties wanted no part in another world holocaust. The First World War had resulted in the establishment of Communist tyranny in Russia. The punitive peace which followed had stunted the growth of democracy in Germany and eventually led to the destruction of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of Nazi tyranny in Germany. The Versailles Treaty had also converted Eastern Europe into a hodgepodge of unviable small states whose peoples were worse off, and enjoyed less liberty and opportunity, than under the Austro-Hungarian Empire which Wilsonian principles had split up into antagonistic parts. And who would say that these peoples enjoyed any advantage and were not endangering their own existence by being utilized by France for the purpose of “containing” Germany? A second war “to make the world safe for democracy” was unlikely to lead to any better results and might prove disastrous to Western civilization.

Today it would seem almost certain that the policy advocated by American noninterventionists would have been more beneficial to Britain as well as to the rest of the world than that of the powerful Anglophiles and other interventionists. In a famous speech which brought opprobrium on his head, Lindbergh said on April 23, 1941:

“I have said before, and I will say again, that I believe it will be a tragedy to the entire world if the British Empire collapses. This is one of the main reasons why I opposed this war before it was declared and why I have constantly advocated a negotiated peace. I did not feel that England and France had a reasonable chance of winning. France has now been defeated; and, despite the propaganda and confusion of recent months, it is now obvious that England is losing the war. I believe this is realized even by the British Government. But they have one last desperate plan remaining. They hope that they may be able to persuade us to send another American Expeditionary Force to Europe, and to share with England militarily, as well as financially, the fiasco of this war.”

“I do not blame England for this hope, or for asking for our assistance. But we now know that she declared a war under circumstances which led to the defeat of every nation that sided with her from Poland to Greece. We know that in the desperation of war England promised to all those nations armed assistance that she could not send. We know that she misinformed them, as she has misinformed us, concerning her state of preparation, her military strength, and the progress of the war.”

Following Germany’s attack on Russia, those who knew something about communism foresaw that American intervention would in all probability result in creating what Churchill recognized too late as “worse perils.” For instance, Professor Nicholas Spykman of Yale wrote in a book published shortly after Pearl Harbor (Americas Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power) that the annihilation of Germany and Japan would open Europe to Soviet domination and observed: “A Russian State from the Urals to the North Sea can be no great improvement over a German State from the North Sea to the Urals.”

Ex-President Herbert Hoover was among those who had the wisdom and foresight to realize that our aid to Communist Russia would have disastrous consequences. In June, 1941, when Britain was comparatively safe from German invasion thanks to Hitler’s attack on Russia, he said (as recalled in his broadcast August 10, 1954) that “the gargantuan jest of all history would be our giving aid to the Soviet Government.” He urged that America should allow the two dictators to exhaust each other and prophesied that the result of our assistance would be “to spread communism over the world.” Whereas, if we stood aside the time would come when we could bring “lasting peace to the world.”

President Roosevelt was undeterred by this and other prophetic voices. He was determined to get the United States into the war by one means or another in spite of the reluctance or positive refusal of the American people to become involved.

Step by step from the Lend-Lease Act to the Atlantic Conference in August, 1941, the President had resorted to both open and covert acts contravening the international laws which circumscribe the action permissible to neutral powers and directly contrary to the intent of Congress and the American people. Acts “short of war” taken to help Britain were succeeded by belligerent action when secret orders were given to the Atlantic fleet on August 25, 1941, to attack and destroy German and Italian “hostile forces.” This order came two weeks after the Atlantic Conference, at which Roosevelt had said to Churchill, “I may never declare war; I may make war. If I were to ask Congress to declare war, they might argue about it for three months.” Following the Greer incident in which an American destroyer fired on a German submarine, the President on September 11 made his shoot-on-sight speech in which he called the Nazi submarines and raiders “rattlesnakes”: said that “when you see a rattlesnake poised to strike you do not wait until he has struck before you crush him,” and stated that henceforth “if German or Italian vessels of war enter the waters the protection of which is necessary to American defense, they will do so at their own peril.”

Thus we should have been openly involved in the war months before Pearl Harbor had it not been for Hitler’s evident determination not to be provoked by our belligerent acts into declaring war on us. Count Ciano in his diaries, published after the war, wrote that the Germans had “firmly decided to do nothing which will accelerate or cause America’s entry into the war.”

Roosevelt had carried Congress along with him in his unneutral actions by conjuring up the bogey of an anticipated attack on America. We now know, thanks to exhaustive examination of the German secret archives at the time of the Nuremberg trials, that there never was any plan of attack on the United States. On the contrary, the tons of documents examined prove that Hitler was all along intent on avoiding war with the United States. He did not declare war on us until compelled to do so by his alliance with Japan.

In the words of the eminent British military historian, Major General J. F. C. Fuller, writing in A Military History of the Western World (p. 629), in 1956:

“The second American crusade ended even more disastrously than the first, and this time the agent provocateur was not the German Kaiser but the American President, whose abhorrence of National Socialism and craving for power precipitated his people into the European conflict and so again made it world-wide. From the captured German archives there is no evidence to support the President’s claims that Hitler contemplated an offensive against the Western Hemisphere, and until America entered the war there is abundant evidence that this was the one thing he wished to avert.”

Extreme provocation having failed to induce Germany to make war on us, and there being no prospect of Congress declaring war because of the determination of the great majority of the American people not to become active belligerents, Roosevelt turned his eyes to the Pacific. It could be that Japan would show less restraint, since it was possible to exert dip...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- CHAPTER I - PRELUDE TO WAR

- CHAPTER II - THE CURTAIN ASCENDS

- CHAPTER III - INVESTIGATED BY THE FBI

- CHAPTER IV - EDUCATION OF A STRATEGIST

- CHAPTER V - THE VICTORY PROGRAM

- CHAPTER VI - GRAND STRATEGY

- CHAPTER VII - PROPAGANDA AND WAR AIMS

- CHAPTER VIII - TO LONDON WITH HOPKINS AND MARSHALL

- CHAPTER IX - PRESENTING AMERICAN STRATEGY IN LONDON

- CHAPTER X - STRATAGEMS IN LIEU OF STRATEGY

- CHAPTER XI - “TORCH” BEGINS TO BURN

- CHAPTER XII - CASABLANCA

- CHAPTER XIII - UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER

- CHAPTER XIV - AROUND THE WORLD IN WARTIME

- CHAPTER XV - REFLECTIONS ON STRATEGY

- CHAPTER XVI - PATTON IN COMBAT

- CHAPTER XVII - THAT “SOFT UNDERBELLY”

- CHAPTER XVIII - FROM “TRIDENT” TO QUEBEC

- CHAPTER XIX - EASED OUT TO ASIA

- CHAPTER XX - FIRST MONTHS IN CHINA

- CHAPTER XXI - STILWELL, HURLEY, AND THE COMMUNISTS

- CHAPTER XXII - TOWARD VICTORY

- CHAPTER XXIII- AFTER VICTORY

- CHAPTER XXIV - DIVERSE VIEWS ON POLICIES

- CHAPTER XXV - MY LAST MISSION TO CHINA

- CHAPTER XXVI - THE WAR NOBODY WON: 1

- CHAPTER XXVII - THE WAR NOBODY WON: 2

- CHAPTER XXVIII - CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX I - SALE OF WAR SURPLUSES IN CHINA

- APPENDIX II - MEMORANDUM FOR COLONEL HANDY:

- APPENDIX III - MEMORANDUM FOR MR. CONNELLY

- APPENDIX IV - THE PARAPHRASE OF THE AUTHOR’S MESSAGE TO THE WAR DEPARTMENT

- APPENDIX V - DIRECTIVE TO LIEUTENANT GENERAL WEDEMEYER

- APPENDIX VI - REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT, 1947, PARTS I-V

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wedemeyer Reports! by General Albert C. Wedemeyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.