- 121 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

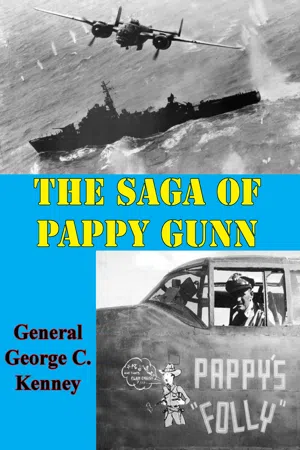

The Saga Of Pappy Gunn

About this book

FOUR-STAR GENERAL KENNEY pays a remarkable tribute to a remarkable man in this biography. Colonel Paul Irwin ("Pappy") Gunn met a tragic death in an airplane accident in the Philippines on October 11, 1957. Believing that our country owes a debt to a great character, a superb aviator, and a devoted American that has never been paid, General Kenney has written this story in the hope that it will help discharge a part of that debt.

General Kenney's own words serve better than any others to describe this book:

"This is the story of an extraordinary character. He was one of the great heroes of the Southwest Pacific in World War II, a mechanical genius, and one of the finest storytellers I have ever known. His deeds were real. His stories were often fantasies but they will be told and retold as long as any of his comrades-in-arms are still alive and then will be handed down to succeeding generations of airmen. Pappy Gunn is already a legendary figure."

The saga of Pappy Gunn contains a wealth of stories, Spectacular things happened to this spectacular person....As the author points out, "He lived, died, and was even buried differently from other people." Faithfully, but with humor and warmth and understanding, General Kenney has constructed the life story, the saga, of his friend, Pappy Gunn.

General Kenney's own words serve better than any others to describe this book:

"This is the story of an extraordinary character. He was one of the great heroes of the Southwest Pacific in World War II, a mechanical genius, and one of the finest storytellers I have ever known. His deeds were real. His stories were often fantasies but they will be told and retold as long as any of his comrades-in-arms are still alive and then will be handed down to succeeding generations of airmen. Pappy Gunn is already a legendary figure."

The saga of Pappy Gunn contains a wealth of stories, Spectacular things happened to this spectacular person....As the author points out, "He lived, died, and was even buried differently from other people." Faithfully, but with humor and warmth and understanding, General Kenney has constructed the life story, the saga, of his friend, Pappy Gunn.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Saga Of Pappy Gunn by General George C. Kenney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 — “Pappy” And The Whale

The Time—mid-afternoon, July 28, 1943.

THE PLACE—the Bismarck Sea just northeast of Cape Gloucester on the west end of the Island of New Britain.

THE TARGET—two Japanese destroyers steaming west at full speed after being discovered by an American reconnaissance airplane.

FOR NEARLY a week Lieutenant Colonel Paul I. “Pappy” Gunn had been at Three Mile Airdrome at Port Moresby, New Guinea, waiting for a chance to test our latest gun-air-plane combination. It was a 75-millimeter cannon mounted in the nose of the B-25 or Mitchell bomber. Pappy had fallen in love with it as soon as he saw it, and begged me to let him test it against the first Jap vessel that came within range. I told him to join the 3rd Attack Group, my pet skip-bombing boys, and I would see that he got the first shot at the target. Pappy had been a member of that outfit before I attached him to my own staff and made him a Special Projects officer. The 3rd Group called him “The General’s Uninhibited Engineer,” but they were proud of his accomplishments and the unorthodox methods he used to attain them. They were sort of unorthodox themselves.

Shortly after noon, a radio flash from one of our reconnaissance planes gave us the news Pappy and the 3rd Group gang had been waiting for. With Gunn’s B-25 in the lead, in fifteen minutes thirty-six bombers were on their way. The weather was spotty, with fairly large patches of rain areas and poor visibility, so the group broke up into three squadrons of twelve planes each and fanned out to cover a wide front and be sure of intercepting the two Jap ships. The planes cruised along just over the waves and islands and coral reefs, never over a hundred feet from the ground or water. These were the low-altitude boys who boasted that they didn’t carry oxygen because they didn’t fly high enough to use it and that if on a flight they came across a cow, they flew around it. They were also “the skip-bombing gang” who came roaring into the attack at wave-top altitude and skipped their bombs up against the sides of enemy vessels, hurdled the masts, and waited for the four-second delay fuses to detonate the bombs. In that brief time, traveling at nearly five hundred feet per second, they would get out of danger from being hit by their own bomb fragments or pieces of the enemy ship. It was a hair-raising type of attack, but it was succeeding beyond all our original expectations. Moreover, the 3rd Group had the lowest combat casualty record in the whole Fifth Air Force, and all the rest of the groups were busy training their crews to follow the 3rd’s example.

Shortly after two-thirty, the squadron, with Pappy in the lead, broke through a rain squall into clear weather, and there dead ahead less than two miles away were the two Jap destroyers heading for a big fog bank about a mile to the west. There was no time to jockey for position, for the wake behind the vessels showed they were moving at top speed to get under cover. Pappy signaled for the attack and at a distance of 1,500 yards opened fire on the leading and largest of the two ships. He had six shells for his 75-millimeter gun. The projectile part, about three inches in diameter, weighed sixteen pounds, of which a pound and a half was TNT.

The first shot hit one of the destroyer’s stacks, the second ricocheted along the deck knocking out an antiaircraft gun position. Number three missed altogether, and number four was square in the middle of the hull. Pappy was so close now that he had to pull up, hurdle the ship, and turn around for another pass. One trouble was that the destroyer didn’t seem to pay any attention to that little three-inch hole and was still steaming along at a good thirty-five knots.

Pappy’s two wingmen sized up the situation. There was only time for one more pass before the Jap ships would be getting under cover of the fog bank just ahead of them. They called Gunn on the radio. “Pappy, will you please get the hell out of the way and let us show you how a destroyer ought to be sunk.” Pappy’s reply, properly expurgated and considerably shortened, was “OK, you knuckle heads, I wish this obscene crock carried a few more rounds of ammunition. I’d show you.” The conversation now fell on deaf ears as the two wingmen flying abreast with the throttles wide open, and their twenty-four forward-firing machine guns blazing, came in on the attack. At about two hundred yards from the Jap vessel, each dropped a five-hundred-pound bomb. The pair climbed steeply barely missing the masts and stacks. Two explosions accompanied by two clouds of mixed flame, smoke, and water with bits of debris obscured the destroyer and told the story even before things cleared up so that the results could be seen and entered in the report to be turned in after the return to the home airdrome. One bomb had blown the whole stern off. The other had penetrated the hull just above the water line, and when it detonated inside, had broken the ship in two. The two halves were already almost out of sight.

The squadron headed back home. The two wingmen swung in behind Pappy to let him lead the return flight. There were no more targets as the second destroyer had also been taken care of by some of the other members of the squadron. Pappy sulked and silently cursed the gang that had shown up both him and his pet gun installation that he had pinned such high hopes on.

As the twelve planes approached Cape Gloucester where the Japs had a little field, Pappy saw a chance to vindicate himself and restore his sunken prestige. A Jap transport plane had just landed and was taxiing along the strip. Skimming over the treetops Pappy’s attack was a complete surprise. The first of the two remaining shells hit the right engine and the second exploded right in the pilot’s cockpit. As he told me afterward, “General, when I passed over that wreck there were pieces of Jap higher than I was.” Pappy’s prestige was now restored. Nobody could kid him now about his new gun installation.

The squadron crossed over the west end of the island of New Britain, passed over a school of whales in the Solomon Sea to the south who looked as though they were playing a type of cetacean water polo, then swung over the eastern end of New Guinea and landed at their home field at Three Mile.

With their reports turned in, the crews lounged around the squadron operations room. They had already forgotten all about the war, and nobody wanted to chide Pappy for not sinking that destroyer. His sulphurous reply could easily set fire to the grass and palm-leaf-thatched operations hut and perhaps to the nearby jungle as well. One of the pilots decided to break the silence, but he would keep away from any dangerous reference to the mission they had just returned from.

“Say Pappy,” he said, “did you see those whales we passed over in the Solomon Sea.”

“Yeah,” replied Pappy, “I saw them.” Then his eyes suddenly seemed to light up, and he cleared his throat. The gang gathered around us as if a signal had been given. Pappy was about to tell one of his stories, and they weren’t going to miss a word of it.

“You may not know it,” said Pappy, “but the whale is the most intelligent of all animals. He not only has brains, but he’s a friendly guy. He likes people and wants to do things for them. If he wasn’t so damn big, he’d make a wonderful house pet.

“Those whales out there today reminded me of the time back in 1930 when I was flying in the Navy. It was during maneuvers off the north coast of Haiti. I was flying a catapult, pontoon job off the cruiser Omaha doing reconnaissance, hunting for the ‘enemy’ submarines.

“There I am one day at five thousand feet and about a hundred miles away from my ship, when all of a sudden the engine quits. I was quite sure I knew what it was. You see, in those days they used to put hose connections in the gas lines. Those old motors used to vibrate so, they were afraid the lines would break if they didn’t give ‘em some flexibility. Sometimes the gasoline would rot the rubber, and little bits of it would get in the line or in the carburetor and shut off the fuel from getting through to the engine. I knew what to do if I could just land without cracking up, but when I looked at the old Atlantic boiling away, I figured that when I did get down I was going to be lucky if I had anything left to sit on until I was rescued.

“I spiraled down looking for a wave that was maybe a little smoother than the others when all of a sudden when I’m about two hundred feet high, I see a beautiful wake into the wind just ahead of me.

“I landed in that wake, slide along nice and pretty, and then with just a hint of a jolt I stop. When I looked over the side to see what I had run into, damned if I wasn’t on the back of a whale.

“I sat there for a while but the whale didn’t move, so I said to myself, ‘What the hell! ‘ and got out and stood on the whale’s back, lifted up the cowling, cleaned out the carburetor and gas lines, put on some new hose connections I had in my pocket, and buttoned the cowling up again. Then I got the crank for the inertia starter out of the plane, stood there with one foot on the whale and the other on a pontoon, and cranked away until I got the fly wheel spinning fast. Now I get into the cockpit, turn on the ignition, and let in the fly wheel clutch. The prop turns over, the engine takes, and Fin in business. Now the whale—remember I told you how smart they are—he knows I’m ready to go so he softly submerges being careful not to flick his tail and maybe hit the plane. About a hundred feet out ahead of me, he surfaces, turns into the wind, and gives it full power as he makes another long smooth wake for me to take off on and come back to the Omaha”

Pappy looked around grinning happily, waited a few seconds for the applause, which he got, and turned to go. “I guess I’d better see if Sergeant Evans has got that ship of mine ready to go out on another mission/’ he said and walked out of the hut toward the flying line.

2. — A Boy’s Dream

PAUL IRVIN “PAPPY” GUNN was born in Quitman, Arkansas, a little village of about eight hundred people some forty-five miles north of Little Rock, on October 18, 1900. If you check on his military records in the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., you will find the date of Pappy’s birth is a year earlier, but that minor error is because of his desire to avoid embarrassing questions from the navy recruiting officer in Little Rock on August 8, 1917, the date of his first enlistment. The new recruit was not yet eighteen at that time and there probably would have been a matter of parental consent involved. Anyhow, the little discrepancy in giving the exact date of his birth was not important to Pappy then or from then on.

His father, Nathaniel Hezekiah Gunn with his wife, Laura Litton Gunn, and their six children had moved to Quitman in 1896, bought fifty-five acres of land, and built a six-room frame house and a barn. In addition to farming and fruit growing, Nathaniel was a livestock dealer, buying cattle and driving them overland to Little Rock or to Kensett, a railroad-junction town fifty miles southeast of Quitman for shipment on the Missouri Pacific Railroad to the St. Louis market. Whenever the subject came up, “Pappy” always said his father was a mule skinner from the Ozark Mountains and that he had followed in his footsteps before enlisting in the Navy. The Gunns, like the rest of the local farmers, always had a span of mules. That probably furnished enough background for Pappy’s story. In fact, it was more background than he generally needed on which to build the fantastic stories that his listeners looked forward to.

In August 1907 Nathaniel died. The five oldest children, Pearl, Lish, Dess, Dorris, and Claudine, by this time were all married and living away from home. Mrs. Gunn didn’t feel that she could work the farm so she rented it and with the remaining four children, Jewell, now eleven, and the three new arrivals since the family had moved to Quitman, Charles, nine, Paul Irvin, seven, and Litton, five, moved to a small house in town. The following March, during a windy night, the house burned to the ground, the family barely escaping with little more than their nightclothes. That spring and summer, Laura and the children lived with her married daughter Claudine and two of the married sons, Dorris and Lish.

In the fall the family was reunited when Laura moved them to a farm near Lonoke, twenty-five miles east of Little Rock, where her brothers Jim and Charley Litton had plantations. The Gunn family lived there three years, growing cotton and some garden truck. A hired man did the plowing and the family did the planting, hoeing, and gathering of the crops. The school system was adjusted to fit the farm schedule. The one-room schoolhouse took care of the first six grades. A three-month term in winter and another three months in summer gave the youngsters time to do the spring planting and cultivating and gather the crops in the fall when the cotton had to be picked and carted to the gin in Lonoke.

It was on one of these trips to town one day in 1908 that Charley and Paul decided to walk home. They had just started when an automobile, the first one they had ever seen, overtook them. The driver stopped and offered them a lift. The two open-mouthed lads got aboard too overcome to do anything but nod their consent. In grand style, to the astonishment of the neighbors and consternation of the chickens and livestock, they arrived in front of their house, and, getting out, ran to their mother standing on the front porch. After the car had gone and the dust settled they discovered that one of their pigs was lying in the road dead. The topic of conversation for the next month or two had nothing to do with the loss of the pig. The great adventure in the wonderful automobile was told and retold by Paul on every occasion, and each time it was a better story with more and more emphasis on the size, power, and speed of the car. He had decided that someday he was going to drive one of those things.

His ambition lasted until the fall of 1910 when one day, while the family was in the cotton field, an airplane flew over-head. Paul, then a thin, wiry, blue-eyed kid of ten, watched until it was out of sight, then turned to his mother and said, “Someday I’m going to fly like that.” This was the dream that he now began to live. He liked to draw. At first automobiles and later airplanes appeared in chalk on fences and the sides of the barn. His teachers encouraged and helped him, and it wasn’t long before his pen-and-ink sketches and drawings of airplanes in considerable detail began to adorn the walls of his room. He read everything that mentioned aviation and talked about flying constantly, sometimes to the amusement of the neighbors but more often with much shaking of heads and thankfulness that their youngsters didn’t have such crazy ideas as that Gunn boy. The rest of his family tolerated Paul’s enthusiasm but certainly did not share or approve of his dreams of someday becoming an aviator.

In 1911 the family moved back to Quitman. The town located at the edge of the Ozarks was on higher ground than Lonoke and had a much more healthful climate. The “chills and fever” of the latter location was getting to be too much for them, so Laura moved back to the old farm and the frame house Nathaniel had built fifteen years before.

They didn’t have any recognition in those days for “Mother of the Year.” If they had had, Laura would have been a real contestant. The four youngsters now ranging from Litton’s nine years to Jewell’s fifteen helped her to run the farm, but the main burden fell on Laura, who had determined to make good citizens of all of them. It would add to her work, but they must be educated and brought up to be a credit to her and the community. Her own religious instruction supplemented that of the Sunday school and the church. Plowing, seeding, cultivating, gathering crops, and building up the insatiable woodpile for cooking and heating took a lot of the family’s time, but Laura saw to it that they attended school whenever they could be spared. Many times she carried the load herself so that they wouldn’t miss an important class or an examination.

She believed in discipline and the old idea that children should be obedient, respectful, and law-abiding. If necessary, and when talking did not bring the desired results, she was pre-pared to use the rod rather than spoil the child. Paul used to recall, when talking about his mother, whom he adored, an occasion when he had shirked a hoeing job to go fishing. When he returned home proudly displaying a good string of fish, Laura invited him into the smokehouse where she kept a peach-tree switch. Unfortunately for the lesson in discipline she forgot to shut the door before Paul’s dog, Shep, came in to see what was happening to his master. Paul’s exaggerated yells were too much for Shep. The punishment had to be called off while Paul rescued his mother. However, as he always ended the story, “The next time and from then on, Mother always remembered to close the smokehouse door before she reached for the switch.”

Laura’s system evidently worked. The youngsters got an education and were described by their neighbors as a healthy, well-behaved, and industrious family. One of his former teachers, Edna Clark, now Mrs. J. K. Graves of Mineral Wells, Texas, says of Paul:

“I remember him very well. I knew him as a typical American boy. I was his teacher three years, about 1914 through 1916 in the third, fourth, and fifth grades. He was a good average student, regular in attendance, and he seemed to enjoy the school activities. He liked to draw and he memorized poems very well. I thought a great deal of him as a student and he seemed to like me.”

The children all worshiped the...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FRONT MATTER

- FOREWORD

- 1 - “Pappy” And The Whale

- 2. - A Boy’s Dream

- 3. - A Dream Fulfilled

- 4 - Naval Aviator

- 5. - Pappy Joins The Army Airforce In The Philippines

- 6. - Early 1942 In Australia

- 7. - My Introduction To Pappy

- 8. - Pappy’s Folly- The Skip-Bomber

- 9. - Pappy Visits The United States

- 10. - Pappy In Hollywood

- 11. - The Tale Of A Shirt

- 12 - Promotion Party

- 13. - Practical Joke

- 14. - “I Taught Him How To Fly”

- 15 - The Wicked Digit

- 16 - Back To The Philippines

- 17 - Liberation And Reunion

- 18. - Adjustment To Civil Life

- 19 - Pappy And The Huks

- 20. - Pappy’s Last Flight