![The Battle For Leyte Gulf [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3020869/9781782899112_300_450.webp)

- 175 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle For Leyte Gulf [Illustrated Edition]

About this book

Includes 6 charts and 20 photos

Pulitzer prize winning author C. Vann Woodward recounts the story of the largest naval battle of all time.

"The Battle for Leyte Gulf was the greatest naval battle of the Second World War and the largest engagement ever fought on the high seas. It was composed of four separate yet closely interrelated actions, each of which involved forces comparable in size with those engaged in any previous battle of the Pacific War. The four battles, two of them fought simultaneously, were joined in three different bodies of water separated by as much as 500 miles. Yet all four were fought between dawn of one day and dusk of the next, and all were waged in the repulse of a single, huge Japanese operation.

"They were guided by a master plan drawn up in Tokyo two months before our landing and known by the code name Sho Plan. It was a bold and complicated plan calling for reckless sacrifice and the use of cleverly conceived diversion. As an afterthought the suicidal Kamikaze campaign was inaugurated in connection with the plan. Altogether the operation was the most desperate attempted by any naval power during the war-and there were moments, several of them in fact, when it seemed to be approaching dangerously near to success.

"Unlike the majority of Pacific naval battles that preceded it, the Battle of Leyte Gulf was not limited to an exchange of air strikes between widely separated carrier forces, although it involved action of that kind. It also included surface and subsurface action between virtually all types of fighting craft from motor torpedo boats to battleships, at ranges varying from point-blank to fifteen miles, with weapons ranging from machine guns to great rifles of 18-inch bore, fired "in anger" by the Japanese for the first time in this battle."

Pulitzer prize winning author C. Vann Woodward recounts the story of the largest naval battle of all time.

"The Battle for Leyte Gulf was the greatest naval battle of the Second World War and the largest engagement ever fought on the high seas. It was composed of four separate yet closely interrelated actions, each of which involved forces comparable in size with those engaged in any previous battle of the Pacific War. The four battles, two of them fought simultaneously, were joined in three different bodies of water separated by as much as 500 miles. Yet all four were fought between dawn of one day and dusk of the next, and all were waged in the repulse of a single, huge Japanese operation.

"They were guided by a master plan drawn up in Tokyo two months before our landing and known by the code name Sho Plan. It was a bold and complicated plan calling for reckless sacrifice and the use of cleverly conceived diversion. As an afterthought the suicidal Kamikaze campaign was inaugurated in connection with the plan. Altogether the operation was the most desperate attempted by any naval power during the war-and there were moments, several of them in fact, when it seemed to be approaching dangerously near to success.

"Unlike the majority of Pacific naval battles that preceded it, the Battle of Leyte Gulf was not limited to an exchange of air strikes between widely separated carrier forces, although it involved action of that kind. It also included surface and subsurface action between virtually all types of fighting craft from motor torpedo boats to battleships, at ranges varying from point-blank to fifteen miles, with weapons ranging from machine guns to great rifles of 18-inch bore, fired "in anger" by the Japanese for the first time in this battle."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle For Leyte Gulf [Illustrated Edition] by C. Vann Woodward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I — SORTIE OF THE IMPERIAL FLEET

Only once in the two years that had passed since the hard-pressed, bitterly fought days of Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal had the Japanese Fleet ventured out in strength to offer battle. Even in the critical actions of 1942 nothing like full scale commitments had been made on either side, and while the Battle of the Philippine Sea brought out a large part of the enemy fleet the engagement had been confined to air action. None of our many landing operations in 1943 and, with the single exception of the Marianas, none in the following year had been challenged by major forces of the Japanese Navy.

The westward sweep of our Pacific offensive had by the fall of 1944 converged in two mighty thrusts aimed at the Philippine Islands, flanking them from the east and south. On September 15 simultaneous landings were made on Peleliu Island of the Palau Group and on Morotai in the Moluccas. The Peleliu landing brought the Central Pacific Forces, under the command of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, to the Western Caroline Islands within five hundred miles east of Mindanao. The path of their advance had been westward from the Gilbert Islands through the Marshalls and Marianas. By the landing on Morotai General Douglas MacArthur advanced the frontier of his Southwest Pacific Forces, which had pushed northwest along the coast of New Guinea, to within three hundred miles southeast of Mindanao. The Philippines lay ahead as the next great objective.

Would the landing in the Philippines precipitate the long-awaited event? Would the Imperial Japanese Navy at last be tempted to risk a full scale action with our fleet? In spite of its inferior strength and its long period of hiding, there was reason to believe that the enemy fleet would resist our next assault with an all-out attack. Only a month before the landing took place, Navy Minister Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai told the Japanese Diet that the Combined Fleet remained intact and that the officers and men under Admiral Soemu Toyoda were “imbued with a burning fighting spirit to crush the enemy at the earliest opportunity.” He also observed that “the nearer the enemy approaches the inner line of our solid national defense, the greater will become the difficulties and weaknesses of the enemy.”

These were not altogether idle words of Admiral Yonai. The Japanese Fleet was by no means impotent at this time, and general strategic factors were heavily in the enemy’s favor. While our lines of communication and supply were being stretched to tremendous distances his were being materially shortened. He would fight, moreover, within easy range of scores of his own airfields. The assault upon the Philippines would be unlike any of our landings on the tiny atolls and islands to the eastward, and different from our jungle-locked beachheads in New Guinea. In those operations it had been possible to neutralize enemy airfields. The airfields and emergency strips in the Philippines, some seventy of them operational, would be too numerous to be effectively neutralized and too close to Formosa and the Empire to be cut off from reinforcement. On the other hand, we would be fighting 500 miles from our nearest airfield, entirely dependent upon carrier-based planes for cover and under grave strategic disadvantages. The winding passages through the Philippines, presumably mined and covered by land-based planes, were denied to our forces, while they remained open to those of the enemy.

So impressed was our high command with these disadvantages that as late as mid-September our closely guarded plans for future operations called for three amphibious operations in addition to the two on the 15th before the landing on Leyte Island was to be attempted. The first of these was a landing on Yap Island as a continuation of the Western Carolines campaign by the Central Pacific Forces. This was set for September 26. Mac Arthur’s forces were to move on to Talaud Island, northwest of Morotai, on October 15, and from that steppingsTone they were to leap to southern Mindanao on November 15. The landing in Leyte Gulf was not scheduled until December 20. In prospect the Philippines campaign therefore assumed somewhat the shape of the long struggle for the Solomons and New Guinea. Plans and preparations were made accordingly.

Then came a sudden and dramatic change in the whole concept and strategy of the campaign. A week before the Morotai-Peleliu landings the Third Fleet, under the command of Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., began a series of air strikes which lasted until the 15th and had as their purpose the neutralization of enemy airfields which might interfere with the landings of that date. These attacks revealed much unexpected weakness of the enemy in that area. One of Halsey’s grounded pilots made his way back to the fleet with the aid of Filipino guerrillas bringing information that confirmed this weakness. Halsey’s staff, which had developed the strategy of by-passing in the Solomons, had already discussed the possibility of adapting the same strategy to the Philippines campaign. With the new information in hand, Halsey recommended in a message sent in the early morning hours of the 13th{1} that all intermediary and preparatory landings and operations be dispensed with and that the assault on Leyte Gulf be carried out as soon as possible.

The landings of the 15th went forward as scheduled, but Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur concurred in Halsey’s recommendations for the abandonment of additional landings and promptly forwarded them for approval to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, then attending an inter-Allied conference at the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec. Called hastily from a dinner party, the admirals and generals of the Joint Chiefs quickly approved the change in plans and the proposed target date of October 20 for the Leyte landing. The new plan, which promised to shorten the war by several months, went into effect on the same day, in fact within a few hours of the time it was proposed.

There was now only a little more than one month instead of more than three months in which to prepare for the great offensive in the Philippines. With a gigantic grinding of gears and applying of brakes many vast operations were pulled to a sudden halt and the huge Pacific war machine was reorganized and turned in a new direction.

A large part of the task force intended for the seizure of Yap Island had already departed from Hawaii combat-loaded, while the remainder was embarked and ready to sail the following morning. These ships and troops were at once diverted to the Southwest Pacific by Admiral Nimitz and put under the command of General MacArthur. Later Nimitz placed Vice Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson and the Third Amphibious Force at the disposal of MacArthur for the Leyte operation and greatly augmented the naval forces of Vice Admiral Thomas C Kinkaid, commander of the Seventh Fleet, which was part of Mac Arthur’s command. Large numbers of transport vessels as well as escort carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers were transferred to the Seventh Fleet.

The speed with which the supreme army and navy commands, which had heretofore operated independently, coordinated their plans and forces for this operation was one of the greatest achievements of the Pacific War. All resources of supply, intelligence, ordnance, and all other military services from Washington to Hollandia were set to work at top speed planning, coordinating, administering, training, loading, fueling, and arming in preparation for the great offensive. In the steaming sweat of the New Guinea tropics the operation known by the code name “KING TWO” was mounted.

To add to the complications and difficulties, there occurred in October what Admiral Nimitz pronounced “the greatest change in supply lines of any month in the war up to that time.” This was occasioned by the advancing of the main base of the Pacific Fleet more than a thousand miles westward from Eniwetok, the previous base, to Ulithi, which was seized without opposition on September 21. The stepping up of the Leyte invasion schedule upset carefully balanced logistic scales and caused unexpected shortages. Nature added its contribution in the form of a typhoon which slashed through Ulithi lagoon spreading destruction on October 3. The strategic advantages of this base, however, justified all its shortcomings. Ulithi represented an inescapable challenge to Japanese naval power.

While our base was being advanced westward to Eniwetok and thence a thousand miles to Ulithi, the Japanese base was being withdrawn from Truk all the way to Brunei Bay on the western side of Borneo. For many months the Japanese press and radio had been minimizing the seriousness of the long series of reverses Japan had suffered in the loss of her island empire to the eastward. This propaganda was accompanied by repeated prophecies of the complete destruction of our fleet once it was lured farther west. Speaking in Tokyo of the approaching struggle, Admiral Nobumasa Suetsugu, a pre-war commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, said that it was to be regarded “not as a mere battle for the Philippines but one which will decide whether Japan can maintain or is to be cut off from her communication with the vital resources of the southern regions. For that reason,” he continued, “the outcome of the Philippine operations will be of such a far-reaching nature as to decide the general war situation, and I am certain it will be the greatest and most decisive battle fought.” When the right moment came, he predicted, Japanese forces would “deal the final smashing blow to the enemy.” The bluff was now to be called, and the time was approaching when the boast would have to be made good.

Japanese documents of the highest authenticity, captured before the end of the war, reveal in remarkable detail and clarity the development of Japanese naval strategy and organization after the Battle of the Philippine Sea as well as the background of the fateful decision of the High Command which led to the Battle for Leyte Gulf.

For some time after the Battle of the Philippine Sea, fought on June 19-20, the extent and character of Japanese losses remained unknown in spite of the efforts of our Intelligence. Eventually it was learned that three carriers were sunk, the Hiyo by carrier planes and the Shokaku and Taiho by submarines, and that approximately 400 planes were destroyed. Even more important than the loss of the three carriers was the almost complete destruction of the air groups of three enemy carrier divisions. Only about forty planes and one hundred pilots remained aboard the surviving Japanese carriers at the end of the battle.

Japanese fleet organization underwent extensive changes between June and October of 1944. These changes involved the tacit admission that the backbone of Japan’s carrier-based air power had been all but broken in the Philippine Sea by the Fifth Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. While the enemy set to work at once to rebuild his carrier air groups, he had to start practically from scratch, and the handicap proved too great. In the meantime, Admiral Toyoda, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, regrouped his forces with one object plainly in mind: the strengthening of forces available for surface action in the Western Pacific. Carrier action remained, perforce, hypothetical.

Prior to the action in the Philippine Sea the two principal task forces of the Combined Fleet were the Third Fleet, made up of three carrier divisions with screening cruisers and destroyers, under the command of Vice Admiral Tokusaburo Ozawa, and the Second Fleet, consisting of the two new, powerful battleships Yamato and Musashi, each with nine 18-inch guns, the modernized Nagato with eight 16-inch guns, the two old battleships Kongo and Haruna, with 14-inch guns, three cruiser divisions consisting of ten heavy cruisers, and a squadron of twelve destroyers and one light cruiser. The Second Fleet was commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, To all intents and purposes this arrangement left three Japanese area fleets, consisting of cruisers and destroyers, and a training force of two battleships, a light cruiser, and eight destroyers separated both physically and tactically from the main fighting force of the Combined Fleet and unavailable for a fleet action in the Western Pacific,

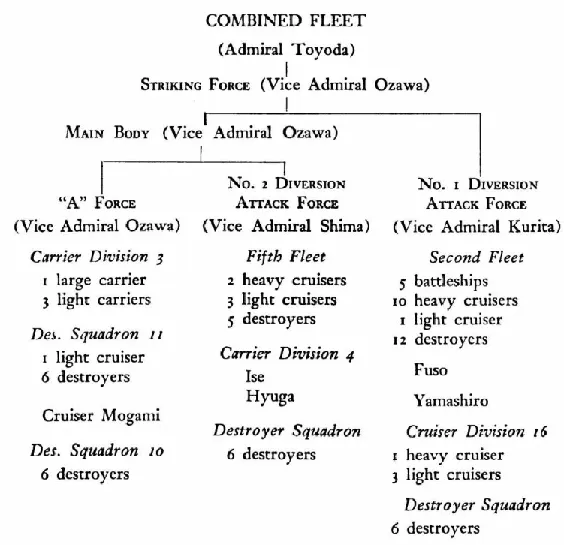

The regrouping of these fleets made them all available for a fleet action under a new organization called the “Striking Force,” placed at first under the command of Admiral Ozawa. The Striking Force was divided into two task forces, the Main Body, containing the remaining carrier strength, and No. 1 Diversion Attack Force, which included the main gun power of the fleet. The latter force consisted of the Second Fleet strengthened by the two battleships Fuso and Yamashiro, and a division of four cruisers and one of six destroyers. Although called a “diversion” force, it constituted the chief instrument of the enemy’s new strategy of surface action. The so-called “Main Body,” likewise confusingly named, contained most of the old Third Fleet as the “A” Force and a No. 2 Diversion Attack Force embracing Vice Admiral Shima’s Fifth Fleet and a newly organized carrier division composed of the Ise and Hyuga, two hybrid battleships with flight decks aft, the first carrier-battleships in naval history. In effect the new organization was as follows:

The base of operations for Admiral Kurita’s No. 1 Diversion Attack Force was designated as Lingga Anchorage, near Singapore, from which, when invasion threatened, it was to advance to Borneo or to the Philippines. The Main Body would remain based temporarily in the Inland Sea of the Empire. Actually the High Command would have preferred to keep the entire fleet based in the Empire, but scarcity of fuel made the transfer of Kurita’s force to Singapore a necessity. Kurita arrived at Lingga toward the end of July and began intensive training for operations against landing force, the attack of ships at anchorage, the conduct of night battles, the use of radar and star shells, and perhaps most important of all, antiaircraft fire. Admiral Ozawa remained in the Empire with his crippled carrier force to expedite the repair of his ships and the training of new pilots and air groups. Japanese intelligence at that time estimated that the next major American landing would probably not come before the first of November. Ozawa hoped that before that time he could complete his preparations, rebuild his air groups, join forces with Kurita to the south, and operate with him against the coming American offensive. Ozawa was racing against time.

It remained to specify the circumstances under which the reorganized fleet would give battle. This was determined by the High Command, which, in effect, drew an imaginary line from Honshu, main island of the Empire, down through Shikoku, Kyushu, the Nansei Shoto (which includes Okinawa), Formosa, and the Philippines. The full force of the Japanese fleet would be thrown at any Allied invasion thrust against this line. Palau and Truk were to be left virtually without hope of naval support, while an invasion of Hokkaido, northernmost island of the Empire, and the Bonin Islands was to be countered only under favorable circumstances. Four sets of operational plans were drawn up, one for each of four areas under threat of invasion. Our concern is with the first only, which was the plan for the naval defense of the Philippines, known as the Sho Plan.

This plan provided that Kurita’s No. 1 Diversion Attack Force sortie from Singapore and proceed toward Brunei Bay or the north central Philippines as soon as the enemy plans were ascertained, and attempt to reach the beachhead during the progress of the landing. It would then “co-operate with our land-based air forces in an all-out attack.” “Avoiding the attack of the [planes of the] enemy task force,” continued the plan, “it will push forward and engage in a decisive battle with the surface force which tries to stop it. After annihilating this force, it will then attack and wipe out the enemy convoy and troops at the landing point.”

The so-called Main Body, based in the Inland Sea, was given as its principal duty the unhappy assignment of acting as a decoy to lure off our fast carrier covering force to permit the battleships to slip through and destroy our invasion shipping. “It will facilitate penetration by No. 1 Diversion Attack Force,” said the plan, “by diverting the enemy [carrier] task force to the northeast and will join in the attack against the flank of the enemy task force.” The impotent state of the Japanese carrier air groups was indicated by several other significant admissions. It was expected that carrier planes would normally return to land bases rather than to their carriers and that carrier air groups might be shore-based under the various base air forces. Under cer...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- CHARTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER I - SORTIE OF THE IMPERIAL FLEET

- CHAPTER II - THE BATTLE OF THE SIBUYAN SEA

- CHAPTER III - THE BATTLE OF SURIGAO STRAIT

- CHAPTER IV - THE BATTLE OFF CAPE ENGAÑO

- CHAPTER V - THE BATTLE OFF SAMAR

- CHAPTER VI - THE END OF THE NAVAL WAR

- APPENDIX-Symbols and Abbreviations