![]()

CHAPTER 1 — The Origins of German Defensive Doctrine

In 1941, the German Army’s doctrine for defensive operations was nearly identical to that used by the old Imperial German Army in the final years of World War I. The doctrinal practice of German units on the Western Front in 1917 and 1918—the doctrine of elastic defense in depth—had been only slightly amended and updated by the beginning of Operation Barbarossa. In contrast to German offensive doctrine, which from 1919 to 1939 moved toward radical innovation, German defensive doctrine followed a conservative course of cautious adaptation and reaffirmation. Consequently, although the German Army in 1941 embraced an offensive doctrine suited for a war of maneuver, it still hewed to a defensive doctrine derived from the positional warfare (Stellungskrieg) of an earlier generation.

Elastic Defense: Legacy of the Great War

The Imperial German Army adopted the elastic defense in depth during the winter of 1916-17 for compelling strategic and tactical reasons. At that time, Germany was locked in a war of attrition against an Allied coalition whose combined resources exceeded those of the Central Powers. The German command team of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff hoped to break the strategic deadlock by conducting a major offensive on the Russian Front in 1917. Therefore, they needed to economize Germany’s strength on the Western Front in France and Belgium, minimizing casualties while repelling expected Allied offensives. To accomplish this, they sanctioned a strategic withdrawal in certain sectors to newly prepared defensive positions. This Hindenburg Line shortened the front and more effectively exploited the defensive advantages of terrain than did earlier positions. This withdrawal was a major departure from prevailing defensive philosophy, which hitherto had measured success in the trench war solely on the basis of seizing and holding terrain. In effect, Ludendorff{6} adopted a new policy that emphasized conserving German manpower over blindly retaining ground—a strategic philosophy whose tactical component was an elastic defense in depth.

To complement his strategic designs, Ludendorff directed the implementation of the Elastic Defense doctrine. {7} This new doctrine supported the overall strategic goal of minimizing German casualties and also corresponded better than previous methods to the tactical realities of attack and defense in trench warfare.

Through the war’s first two years, German (and Allied) doctrinal practice had been to defend every meter of front by concentrating infantry in forward trenches. This prevented any enemy incursion into the German defensive zone but inevitably resulted in heavy losses to defending troops due to Allied artillery fire. Such artillery fire was administered in increasingly massive doses by the Allies, who regarded artillery as absolutely essential for any successful offensive advance. (For example, even the stoutest German trenches had been almost entirely eradicated by the six-day artillery preparation conducted by the British prior to their Somme offensive in 1916.) Consequently, the Germans sought a defensive deployment that would immunize the bulk of their defending forces from the annihilating Allied cannonade.

The simple solution to this problem was to construct the German main defensive line some distance to the rear of a forward security line. Although still within range of Allied guns, the main defensive positions would be masked from direct observation. Fired blindly, most of the Allied preparatory fires would thus be wasted.

General Erich Ludendorff. Ludendorff’s sponsorship caused the Elastic Defence to be adopted by the Imperial German Army during the winter of 1916-17.

In developing the Elastic Defense doctrine, the Germans analyzed other lessons of trench warfare as well. The German Army had realized that concentrated firepower, rather than a concentration of personnel, was the most effective means of dealing with waves of Allied infantry. Too, the Germans had learned that the ability of attacking forces to sustain their offensive vigor was seriously circumscribed. Casualties, fatigue, and confusion debilitated assaulting infantry, causing the combat power of the attacker steadily to wane as his advance proceeded. This erosion of offensive strength was so certain and predictable that penetrating forces were fatally vulnerable to counterattack—provided, of course, that defensive reserves were available to that end. Finally, the Allied artillery, so devastating when laying prepared fires on observed targets, was far less effective in providing continuous support for advancing infantry because of the difficulty in coordinating such fires in the days before portable wireless communications. Indeed, because the ravaged terrain hindered the timely forward displacement of guns, any successful attack normally forfeited its fire support once it advanced beyond the initial range of friendly artillery. {8}

Between September 1916 and April 1917, the Germans distilled these tactical lessons into a novel defensive doctrine, the Elastic Defense. {9} This doctrine focused on defeating enemy attacks at a minimum loss to defending forces rather than on retaining terrain for the sake of prestige. The Elastic Defense was meant to exhaust Allied offensive energies in a system of fortified trenches arrayed in depth. By fighting the defensive battle within, as well as forward of, the German defensive zone, the Germans could exploit the inherent limitations and vulnerabilities of the attacker while conserving their own forces. Only minimal security forces would occupy exposed forward trenches, and thus, most of the defending troops would be safe from the worst effects of the fulsome Allied artillery preparation. Furthermore, German firepower would continuously weaken the enemy’s attacking infantry forces. If faced with overwhelming combat power at any point, German units would be free to maneuver within the defensive network to develop more favorable conditions. When the Allied attack faltered, German units (including carefully husbanded reserves) would counterattack fiercely. Together, these tactics would create a condition of tactical “elasticity”: advancing Allied forces would steadily lose strength in inverse proportion to growing German resistance. Finally, German counterattacks would overrun the prostrate Allied infantry and “snap” the defense back into its original positions.

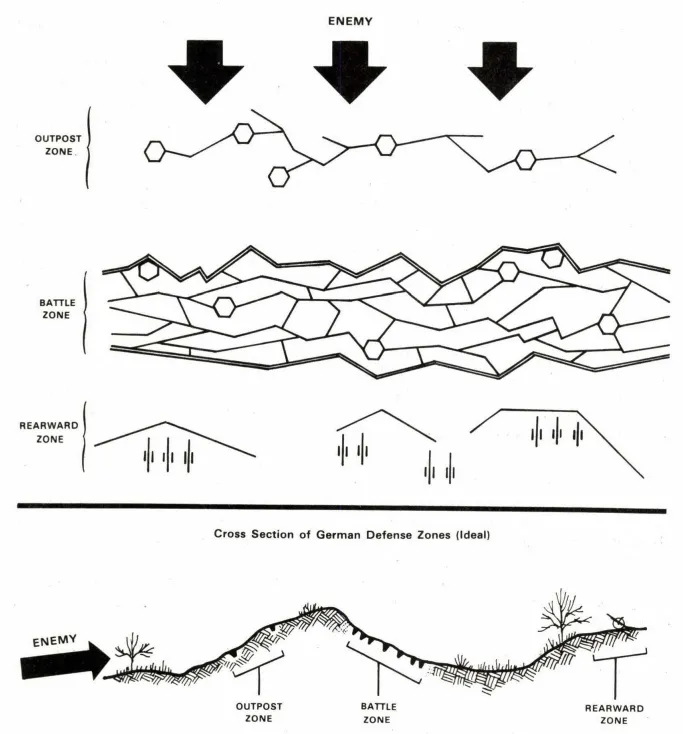

The Germans accomplished this by designating three separate defensive zones—an outpost zone, a battle zone, and a rearward zone (see figure 1). Each zone would consist of a series of interconnected trenches manned by designated units. However, in contrast to the old rigid linear defense that had trenches laid out in parade-ground precision, these zones would be established with a cunning sensitivity to terrain, available forces, and likely enemy action.

The outpost zone was to be manned only in sufficient strength to intercept Allied patrols and to provide continuous observation of Allied positions. When heavy artillery fire announced a major Allied attack, the forces in the outpost zone would move to avoid local artillery concentrations. When Allied infantry approached, the surviving outpost forces would disrupt and delay the enemy advance insofar as possible.

Figure 1. The Elastic Defence, 1917-18

If a determined Allied force advanced; through the outpost zone, it was to be arrested and defeated in the battle zone, which was normally 1,500 to 3,000 meters deep. The forward portion of the battle zone, or the main line of resistance, was generally the most heavily garrisoned and, ideally, was masked from, enemy ground artillery observation on the reverse slope of hills and ridges. In addition to the normal trenches and dugouts, the battle zone was infested with machine guns and studded with squad-size redoubts capable of all-around defense.

When Allied forces penetrated into the battle zone, they would become bogged down in a series of local engagements against detachments of German troops, These German detachments were free to fight a “mobile defense” within the battle zone, maneuvering as necessary to bring their firepower to bear. {10} When the Allied advance began to founder, these same small detachments, together with tactical reserves held deep in the battle zone, would initiate local counterattacks. If the situation warranted, fresh reserves from beyond the battle zone also would launch immediate counterattacks to prevent Allied troops from rallying. If Allied forces were able to withstand these hasty counterattacks, the Germans would then prepare a deliberate, coordinated counterattack to eject the enemy from this zone. In this coordinated counterattack, the engaged forces would be reinforced by specially designated assault divisions previously held in reserve. If delivered with sufficient skill and determination, these German counterattacks would alter the entire complexion of the defensive battle. In effect, the German defenders intended to fight an offensive defensive” by seizing the tactical initiative from the assaulting forces. {11}

The rearward zone was located beyond the reach of all but the heaviest Allied guns. This zone held the bulk of the German artillery and also provided covered positions into which forward units could be rotated for rest. Additionally, the German counterattack divisions assembled in the rearward zone when an Allied offensive was imminent or underway.

In summary, in late 1916, the Imperial German Army adopted a tactical defensive doctrine built on the principles of depth, firepower, maneuver, and counterattack. The Germans used the depth of their position, together with their firepower, to absorb any Allied offensive blow. During attacks, small German units fought a “mobile defense” within their defensive zones, relying on maneuver to sustain their own strength while pouring fire into the Allied infantry. Finally, aggressive counterattacks at all levels wrested the tactical initiative from the stymied Allies...