- 299 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN; A Study In Command

About this book

Although some historians and many newsmen have written many words about Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, U.S. Navy and his brilliant career in the Pacific in World War II, the complete story of this reserved and self-effacing man is now being told for the first time by one of his close friends and wartime associates. The author, Vice Admiral E. P. Forrestel, an important member of Spruance's Staff, was in an ideal position to observe and report on the thought processes of this great and successful naval officer. Spruance's rise to fame came in the Battle of Midway where his sound judgement and wise decisions won a stunning victory over greatly superior enemy forces. That victory reversed the long series of enemy successes and was truly the turning point in the war. From that time on he played an ever increasing part in our naval advance across the Pacific—a task he shared in full measure with another great American naval officer—Admiral W. F. Halsey, U.S. Navy. Tarawa, the Marshall Islands, the Marianas, Iwo Jima and the Ryukyus were important stepping stones along the way that lead to the deck of the U.S.S. MISSOURI in Tokyo Bay where the surrender terms were signed on September 2, 1945. To cap his extraordinarily successful naval career which ended in his Presidency of the Naval War College he accepted an appointment as our Ambassador in the Philippines. Here his wisdom and tact contributed importantly to the satisfactory settlement of a number of troublesome and vexatious problems that disturbed the good relations that should exist between the governments of the Philippines and the United States.

It is given to few Americans to serve their country so effectively and at such high levels as did this man. His career will serve as an example and a challenge to service personnel and diplomats alike. His story will be read avidly by those who suffered his blows in war and by those who are hostile to our country.

It is given to few Americans to serve their country so effectively and at such high levels as did this man. His career will serve as an example and a challenge to service personnel and diplomats alike. His story will be read avidly by those who suffered his blows in war and by those who are hostile to our country.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN; A Study In Command by Vice Admiral E. P. Forrestel USN in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 — The Road to Flag Rank

TWENTY-THREE YEARS elapsed between the end of World War I and the entry of the United States into World War II. The finest training for combat leadership is combat itself, but the United States naval leaders of World War I had long since passed into retirement, and those in positions of leadership at the opening of World War II had, in the first war, been comparatively junior officers, to whom no opportunity for large scale leadership had been presented. Indeed, U.S. Naval operations in World War I were primarily of the escort and convoy type. There was ample experience gained in anti-submarine warfare operations, but none in the kind of large scale amphibious assaults which characterized U.S. naval participation in World War II or the long range duels between fleets or forces, in which the carrier plane was the principal weapon, both offensive and defensive, and in which the ships involved seldom came within gun range of enemy ships.

Historically, we have generally entered each of our wars with the weapons and the tactics with which we came out of the previous war, and to a large degree this was true of our entry into war in 1941. No less an historical authority than Douglas Freeman has observed in a lecture at the National War College that “every war is started by men who had distinguished themselves in the preceding war and they trend to the combinations they had employed tactically rather than to the strategic principles that brought them success.”

As a notable example, Freeman called attention to the record of George Washington, who, when he assumed command of the Continental Army in 1775, had not struck a blow or commanded a troop since the end of December, 1758. In Freeman’s judgment, Washington came to that war with the experience and mental attitude that he had in 1758 and it was three years before he realized that the Revolution was not to be fought according to the methods employed in the French and Indian War.

On the other hand, as an exception to this generalization, Freeman refers to Robert E. Lee. Lee was reared in the Napoleonic tradition and was a student of Napoleonic tactics, but he did not believe that the war of 1861–65 could be fought with those tactics. He realized that he was the first military commander to have railroads and telegraphic communications at his command and he therefore studied and prepared new strategy and tactics based upon the availability of fast transportation and rapid communications.

Weapons and weapons systems had improved during the years between the two world wars, but by and large they had not changed vastly since 1918. Aircraft and aircraft carriers had made great strides forward, but their employment in combat had not been tested. Training during the years had been intensive, but the tactics of World War I were still uppermost in the minds of many, if not most, and these thoughts were not to be dispelled until after our entry into World War II. Most still envisaged the naval war as leading up to and culminating in a classic engagement between battle lines of heavy ships slugging it out against each other with their heavy armament.

When the Japanese struck their well-timed and well-executed attack on Pearl Harbor, they inaugurated a different type of naval warfare, a type to which the United States had not been well trained, but in which it was to develop superb mastery in the succeeding four years. There were at that time some splendid naval officers in positions of great responsibility. After the first blow was received, some did not attune themselves to the changed situation, and their replacement was inevitable. Some who in peace-time training and operations had shown great promise as our future combat leaders did not react as had been expected and it was evident that they would be more useful in other than combat areas. Some, from the first day of the war, showed a cool-headed combat capability, a remarkably far-sighted strategic perspective and an adaptability for the changed tactical employment of forces. Such an officer was Raymond Ames Spruance.

The first son of Alexander P. and Annie Hiss Spruance was born on 3 July 1886, at his mother’s former home in Baltimore, Maryland, where she was visiting shortly after his family had moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. At the age of six, he was sent to New Jersey to live with his maternal grandmother, his three maiden aunts and four uncles, and he spent his early formative years in the care of his grandmother. It was said by the late O. O. McIntyre, newspaperman and author, that being raised entirely or in part by a grandmother is the finest start in life a boy can have. His life there was unspectacular, and there is little out of the ordinary to note in those years, but his grandmother should be credited with instilling in him the foundation of a strong, upright character. His schooling progressed normally but uneventfully; he attended high school in East Orange, New Jersey and when he was thirteen, returned to his family in Indianapolis in time to complete his high school education there at Shortridge High School.

At one time, his father sought to interest him in an appointment to West Point, but when a vacant appointment to the Naval Academy became obtainable from Indiana Senator Fairbanks, he prepared for the entrance examinations, passed them creditably and entered the Academy as a Midshipman on July 2, 1903, one day before his seventeenth birthday. He had also taken a competitive examination for an appointment from New Jersey and won, but preferred to enter from Indiana.

Midshipman Spruance was a serious youth. Appreciative of the opportunity presented to him by his appointment, he was determined to be worthy of it and to show himself deserving of the confidence shown in him by those responsible for the appointment. He applied himself diligently to the task of acquiring an education and learning all he could about the Navy. He was completely undistinguished in athletics and other extra-curricular activities, but nevertheless had the liking and the respect of his classmates and graduated twenty-sixth in his large class, a promising young Passed Midshipman with many friends and no enemies among his classmates.

His Class Book, the 1907 Lucky Bag describes “Sprew”, as he was then called, as “A shy young thing with a rather sober, earnest face and the innocent disposition of an ingenue—Would never hurt anything or anybody except in Line of Duty”.

Here was a competent, conscientious young man, but not one in whom the traits of a future great war-time leader were discernible. The kind of young officer of which he was typical is recognizable. We see one who pays strict attention to his job, a studious type who seeks to know all about his assignment and learns to do it better than anyone else, but who goes about it in that quiet, retiring, almost shy way that draws no attention to himself. He was an independent individual to whom the satisfaction of knowing the right answer or doing the right thing at the right time was more important than praise or recognition. Acclaim for what he considered was simply doing his job was not expected.

His seniors seem at first little attracted to him, but it must be noted that successive fitness reports submitted on him by the same reporting senior become progressively better. It is evident that as time passed, the senior saw that he had an officer whose job was being done well, without fanfare but also without adverse criticism, an officer who was working for the good of the command and who deserved more credit than had at first been apparent.

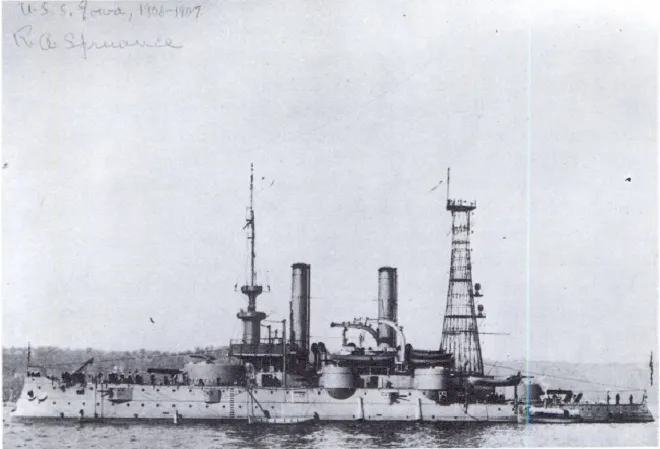

The Naval Academy class of 1907, at that time the largest ever to graduate, was commissioned in three sections in order to distribute the flow of new officers into the fleet. Spruance was with the first section, which graduated on September 12, 1906 and he reported to the U.S.S. Iowa as a Passed Midshipman. There is little of record of his service as a Passed Midshipman, either in the Iowa or in the Minnesota, to which he was transferred in the summer of 1907 and in which he made the celebrated round-the-world cruise of the Great White Fleet. Promotion to the grade of Ensign came through examination after two years of service, and he was so promoted on September 13, 1908.

In the spring of 1909, seeking to broaden and improve himself in his profession, he requested and was ordered to postgraduate instruction in electricity at the General Electric Company in Schenectady, where he served for a year under then Lieutenant Commander Luke McNamee who as a flag officer was later to become one of the Navy’s authorities in the field of electrical communications. Wireless at that time was comparatively new in the fleet and Ensign Spruance, foreseeing its importance, schooled himself in that specialty, one to which few had yet turned, and upon completion of his course and prior to returning to sea duty, he was ordered to duty at the Boston Navy Yard in connection with the installation of electrical under-water communication equipment in submarines.

In May, 1910, he returned to sea duty in the U.S.S. Connecticut, where his commanding officer, Captain W. R. Rush, noted that he showed marked ability as a wireless operator, an ability that was noted by others of his succeeding commanding officers as well.

“Bill” Rush was well known as a very able seaman and disciplinarian who kept a taut but perhaps not too happy ship. He trained his officers well and left an impression on them, but many found him difficult to get along with, and Spruance too, had differences with him, but Captain Rush apparently liked the way this young officer spoke up to him when he thought he was right. In a later report, Rush called him “an excellent example to younger officers in the matter of general conduct, bearing and military appearance, correctness, condition and neatness of uniform”.

In the Connecticut he performed engineering duties and in November, 1911, as a Lieutenant (Junior Grade) went as Senior Engineering Officer to the cruiser Cincinnati, under the command successively of Commanders (later Admirals) S. S. Robison and J. V. Chase.

NR&L (OLD) 1933–A

U.S.S. Iowa (BB 4) Spruance’s first sea duty assignment.

19–N–14525

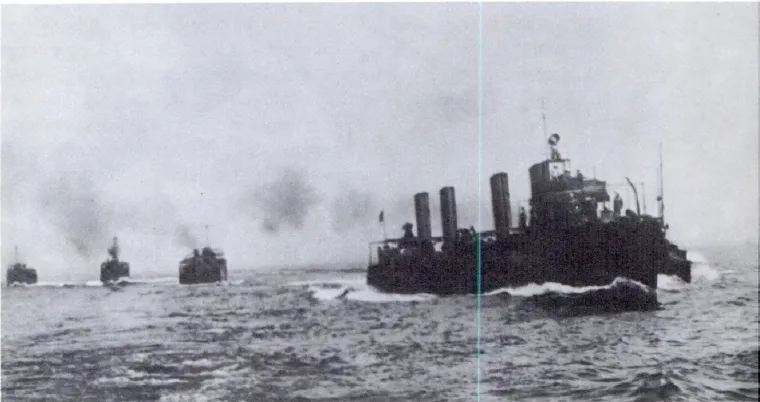

U.S.S. Bainbridge (DD 1) Spruance’s first command.

His first contact with the Far East, an area where he was later to achieve fame, came in the spring of 1913, when he took command of the destroyer Bainbridge, (Destroyer No. 1) of the Asiatic Fleet at Olongapo, Philippine Islands, under the Destroyer Flotilla command of Lt. Commander (later Vice Admiral) Cyrus W. Cole, his former Executive Officer in the Cincinnati. As the senior commanding officer, Spruance also commanded the Destroyer Division which was composed of Destroyers Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

The Asiatic Fleet at that time was known as a hard-working, hard playing, non-regulation force. Lieut. Spruance fitted in as a hard working individual, but he was not hard playing, and in no respect was he non-regulation. Many non-regulation practices were unofficially but customarily accepted in the Asiatic Fleet. This Spruance recognized and accepted good naturedly, but without telling them in so many words, he let his officers and crew know that he expected them to know and do their jobs well and to have a good ship. Without lecturing the crew, but by his day to day general interest in their work as individuals and as a team, by his recognition of ability and performance of crew members and a genuine interest in them as individuals, he fostered in them loyalty to their Captain and the wish to serve him well. He developed in them a self-pride and pride in the ship, and had the kind of command that results when a crew is convinced it has the best skipper of the best crew of the best ship in the best flotilla of the finest Navy in the world. He showed his interest in their health, comfort and welfare by taking over direct, close supervision of the crew’s general mess. As a natural consequence of the Captain’s interest, the ship’s cook redoubled his efforts and served an excellent menu while keeping costs within the ship’s ration allowance; it is a naval maxim that a good general mess makes for a good ship.

Another manifestation of his interest was his taking regular charge of the ship’s swimming party. Swimming was one of his favorite forms of recreation and he was a regular passenger in the boat which took officers and their ladies to the Subic Bay swimming beach daily. Due to the abundance of sharks he was not able there to indulge in long distance, endurance swimming as he did whenever possible throughout his active career.

This consideration and concern for the welfare of his crew and his interest in them as individuals, which was so evident in Lieutenant Spruance’s first command, is to be noted in every one of his succeeding commands, including his Force and Fleet commands in the stress of war.

Under Spruance’s command, the officer complement of the Bainbridge consisted of two younger officers, Lt. (jg) Ralph G. Haxton and Ensign Charles J. Moore. Spruance had not known either of them before, but mutual respect and liking quickly developed between him and each of them and the foundations of firm and lasting friendship were laid. Haxton resigned from the Navy in 1920, but the friendship continued. Moore continued in the Navy, serving again under Spruance at the Naval War College in 1935–37. It will be seen that years later, he selected Carl Moore for the most important job for which it was ever in his power to choose an officer, that of his Chief of Staff and principal advisor in the Central Pacific campaign of World War II.

Here in the Bainbridge, in his first command, we see many traits exhibited which continued to be characteristic of him during his entire career. Although in no sense anti-social, Lieut. Spruance was not a party-goer. He enjoyed informal picnics and mixed sailing parties and dances, of which there were many among Asiatic Fleet personnel, preferring to keep ship good naturedly while his junior officers represented the Bainbridge socially. He did not disapprove of social participation by others and in fact enjoyed listening later to the telling of what had happened at this or that party. He was abstemious, but did not object to the reasonable indulgence of others and would himself participate ashore when it was socially the thing to do.

Although inherently a quiet man, he was even then inquisitive and informed and an interesting conversationalist on a wide range and variety of subjects. An avid reader, he kept up to date on and was conversant with world affairs. It was his expressed belief that every well-educated U.S. citizen had a duty to familiarize himself with the broad field of government, extending into the field of international relations. He recognized that in a democratic government like ours, based upon universal suffrage, foreign policies cannot be expected to be much in advance of the thinking of the majority of the voting public, and that, therefore, knowledge of political and economic happenings and trends outside the United States is essential to a realization of the lines of foreign policy along which the real interests of the country lie. He believed that those with the mental equipment to do so had a special duty to inform themselves on world affairs and to help educate and guide the rest of the country in that respect. During his first tour of duty in the Philippines he inquired into and took great interest in Filipino politics and legislative affairs, an interest which helped make him an understanding and informed ambassador to the Islands forty years later.

In May, 1914, having completed his tour of duty with the Asiatic Fleet, Lt. Spruance was ordered as Assistant Inspector of Machinery at the Newport News Shipbuilding Corporation and later that year Margaret Vance Dean of Indianapolis and he were married. The two children of this marriage seem to have inherited a love of the Navy. The son is now Captain Edward D. Spruance, U.S.N. and the daughter Margaret is the wife of Captain...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- A FOREWORD

- Introduction

- Preface

- Illustrations

- List of Charts

- Abbreviations and Ship Symbols

- Aircraft Designations

- Code Names for Operations

- CHAPTER 1 - The Road to Flag Rank

- CHAPTER 2 - ComTen and ComCaribSeaFron

- CHAPTER 3 - ComCruDiv Five

- CHAPTER 4 - The Battle of Midway

- CHAPTER 5 - Chief of Staff, U.S. Pacific Fleet

- CHAPTER 6 - Preparing for the Gilberts

- CHAPTER 7 - Planned Support

- CHAPTER 8 - Movement to the Objective

- CHAPTER 9 - The Gilberts Secured

- CHAPTER 10 - The Marshall Islands Operation

- CHAPTER 11 - The Mariana Islands Operation Opens

- CHAPTER 12 - The Battle of the Philippine Sea

- CHAPTER 13 - The Mariana Islands Secured

- CHAPTER 14 - The Iwo Jima Operation

- CHAPTER 15 - The Okinawa Operation

- CHAPTER 16 - The War Ends

- CHAPTER 17 - Completion of a Naval Career

- CHAPTER 18 - Ambassador to the Philippine Republic

- Epilogue

- APPENDIX I - Decorations and Awards - Admiral Raymond A. Spruance

- APPENDIX II - Battle of Midway

- APPENDIX III - Gilbert Islands Operation

- APPENDIX IV - Marshall Islands Operation

- Appendix v - Strike on Truk, 17-18 February, 1944

- APPENDIX VI - Mariana Islands Operation

- APPENDIX VII - Battle of the Philippine Sea

- APPENDIX VIII - Iwo Jima Operation

- APPENDIX IX - Okinawa Operation