eBook - ePub

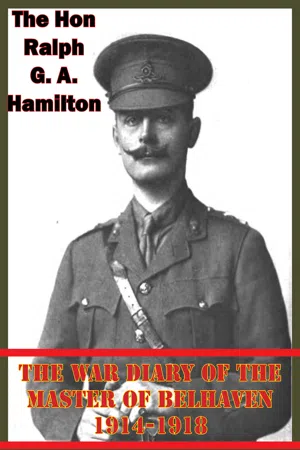

War Diary Of The Master Of Belhaven 1914-1918

- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

War Diary Of The Master Of Belhaven 1914-1918

About this book

Includes 29 maps.

"The author of this diary is an artillery officer who served on the Western Front from 1 Sep. 1915 till his death in action on 31st March 1918, and it is one of the best, ranking alongside Old Soldiers Never Die and The Journal of Private Fraser. Following two brief spells in 1914/1915 with the BEF during the first of which he was injured when his horse fell on him, he arrived in France on 1st Sep. 1915 as OC 'C' Battery, 108 Brigade RFA, 24th Division and before the end of the month he was in the thick of it at Loos. His description of the scene is graphic. He writes about trying to get his guns forward on roads jammed with traffic, trying to find the infantry brigade he was supposed to support, floundering about in the dark under heavy shellfire in an enormous plain of clay having the consistency of vaseline, devoid of any landmark or feature, covered in shell holes...Later he gives a vivid account of the German gas attack at Wulverghem on 30 April 1916, when a mixture of chlorine and phosgene was used causing 338 casualties in the division. During Aug. and Sep. 1916 his division took part in the bitter fighting for Delville Wood and Guillemont, and the diary entries for this period provide some of the most powerfully descriptive writing recorded in any memoirs...He was in action at Messines in June 1917 and a month later at Third Ypres. In Aug. 1917 he was finally given command of a brigade, 108th Brigade RFA still in the 24th Division. When the Germans struck on 21st March 1918 Hamilton was on leave in the UK, but he quickly managed to get back to his brigade, which was in action near Rosieres, a few miles east of Amiens. On 31st March he was killed when a shell burst under his horse just as had happened in Oct. 1914; on that occasion he got away with an injury, this time there was no reprieve..."-Print Ed.

"The author of this diary is an artillery officer who served on the Western Front from 1 Sep. 1915 till his death in action on 31st March 1918, and it is one of the best, ranking alongside Old Soldiers Never Die and The Journal of Private Fraser. Following two brief spells in 1914/1915 with the BEF during the first of which he was injured when his horse fell on him, he arrived in France on 1st Sep. 1915 as OC 'C' Battery, 108 Brigade RFA, 24th Division and before the end of the month he was in the thick of it at Loos. His description of the scene is graphic. He writes about trying to get his guns forward on roads jammed with traffic, trying to find the infantry brigade he was supposed to support, floundering about in the dark under heavy shellfire in an enormous plain of clay having the consistency of vaseline, devoid of any landmark or feature, covered in shell holes...Later he gives a vivid account of the German gas attack at Wulverghem on 30 April 1916, when a mixture of chlorine and phosgene was used causing 338 casualties in the division. During Aug. and Sep. 1916 his division took part in the bitter fighting for Delville Wood and Guillemont, and the diary entries for this period provide some of the most powerfully descriptive writing recorded in any memoirs...He was in action at Messines in June 1917 and a month later at Third Ypres. In Aug. 1917 he was finally given command of a brigade, 108th Brigade RFA still in the 24th Division. When the Germans struck on 21st March 1918 Hamilton was on leave in the UK, but he quickly managed to get back to his brigade, which was in action near Rosieres, a few miles east of Amiens. On 31st March he was killed when a shell burst under his horse just as had happened in Oct. 1914; on that occasion he got away with an injury, this time there was no reprieve..."-Print Ed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access War Diary Of The Master Of Belhaven 1914-1918 by The Hon Ralph G. A. Hamilton (Master of Belhaven) in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE WAR DIARY OF THE MASTER OF BELHAVEN

WHEN war was declared I was in command of the Essex Horse Artillery, and remained with them all August and September. When I found that there was no chance of my battery going on active service, I hunted round to see in what possible capacity I could get out to the Front. I at last discovered that officers with a knowledge of French and German were being taken as interpreters, and with great difficulty I persuaded the War Office to accept me in this capacity.

At the end of September I was informed that I had been appointed interpreter with the 7th Division, then being formed, and was ordered to report myself immediately at Lyndhurst, near Southampton.

On arriving there, being a gunner, I was posted to the 22nd Field Artillery Brigade, commanded by Colonel Fasson.

On Sunday, the 4th October, we suddenly received orders to embark. The division marched to Southampton in ship-loads, but there was considerable confusion and my ship carried Headquarters 22nd Field Artillery, Headquarters 22nd Infantry Brigade, a Signal company, and half a battalion, besides various odds and ends.

We marched out from Lyndhurst at midnight on the 4th-5th and embarked at daylight on Monday, the 6th October. We sailed at 9 o'clock in the morning, without any knowledge of where we were going.

Our first orders were to call at the south side of the Isle of Wight, near Ventnor, after which we steered a course which we thought would bring us to Bordeaux. Great excitement prevailed on board all day as to where we were going, and we followed the course of the ship with our compasses and maps.

During the afternoon the ship suddenly turned about and headed straight up Channel. We now knew our destination could not be Bordeaux or St. Nazaire, and we felt sure it must be either Havre or Boulogne. Our astonishment can be imagined when late in the afternoon we again altered our course and headed north-west in the direction of England.

Soon after dark we came opposite the lights of a large town, which the captain informed us was Folkestone, and eventually came to anchor outside the harbour of Dover. Here we were met by an Admiralty tug, which told us to remain outside the harbour all night, at the same time giving us the cheering news that there were several German submarines in the neighbourhood.

The whole of the 6th we spent moored against the outside mole of Dover Harbour and we were unable to communicate with the shore.

Meanwhile, large numbers of other troopships arrived, and by the evening the whole division was concentrated in Dover Harbour.

As soon as it was dark we left the harbour and proceeded, with all lights out, in a northerly direction. It was a very strange sight to see this fleet of troopships steaming through the night, one behind the other, each with a torpedo destroyer on our northern side. The captain still did not know where we were going. We knew, however, that the British mine-field extended across the Channel and that we must be passing through it.

We spent another cold and very uncomfortable night on the deck of our boat, which, I may say, was a cattle-boat usually running between Canada and Liverpool. I believe these cattle-boats pride themselves on never washing their decks, and certainly it must have been many years since ours had indulged in such a luxury.

At dawn the next morning, the 7th, we found ourselves anchored off a low-lying coast and were told that we had arrived at Zeebrugge. None of us had ever heard of this place before, but we soon found it on the maps and discovered that we were on the Belgian-Dutch frontier. Zeebrugge has a very large mole extending half a mile into the sea, and there was room for five large transports to lie alongside at once.

We commenced landing about ten o'clock and quickly got our horses on shore. We then received orders to rendezvous—marching independently—at Oostcamp, a small village some five miles south of Bruges.

We arrived there, after a march of about twenty miles, just after dark. This march was one of the most extraordinary experiences I have ever had. The wretched Belgians, who for weeks had expected to be overrun by the Germans and treated in the usual Teuton manner, went absolutely mad at seeing the British troops. Passing through Blankenberg, we were fairly mobbed, and it was with the greatest difficulty that we forced our horses through the crowd, who pressed cigars, apples, and Belgian flags on us in thousands.

This continued all the way, and by the time we had passed through the streets of Bruges we looked more like a Bank Holiday crowd than soldiers. Every gun and waggon was decorated with large Belgian flags; most of the men had given away their badges and numerals, and all were wearing flowers and ribbons of the Belgian colours. I shall never forget seeing Colonel Fasson riding at the head of his brigade, clutching an enormous apple in one hand, whilst the Belgian girls were stuffing cigars into his pockets.

My horse—whom I call Bucephalus, because of his carthorse-like appearance—was completely upset, and, the streets being very slippery, I expected him to come down at every moment.

By the time we reached Bruges it was dark, and, there being no staff officers or guides to show us the way to Oostcamp, I went on ahead of the column, with a small party, to find the way.

It was then, to my horror, that I discovered that neither French nor German was of the slightest use, as the language of the country was Flamande—a horrible mixture of bad Dutch and worse German.

We eventually arrived at Oostcamp and were told to go into billets. Our headquarters were in a large château belonging to Count ——. We were most hospitably received, and sat down to an excellent dinner with our hosts. The owner and his wife had fled to Paris, but the château was being used by his brother and sister-in-law, Count and Countess Henri ——. These latter had escaped from their own estate, which was near Liége, with the greatest difficulty, as the Germans entered their park from the other side. They had heard that the Germans had looted and burnt everything, but they were very pleased to have got away safely themselves. Their small boy, aged about twelve, told me with pride that he had been in the Belgian trenches whilst the Germans were bombarding them, and I am not at all sure that he had not been firing a rifle himself.

We expected to be given the next day to collect the rest of the brigade and get straight before advancing. We heard that the Germans were some thirty miles off, and that there was a line of Belgian outposts between us and them.

At 4 o'clock in the morning, 8th October, I was awakened by the adjutant, who came into my room and told me that orders had been received that we were to retire immediately, and, if possible, reach Ostend before night, no explanation of this manoeuvre being given.

We started before dawn and, marching all day, we reached the canal three miles south-east of Ostend by 5 o'clock in the evening. The infantry took up an outpost line on the canal, on the line Oudebrugge-Zandvoordebrugge-Plassehendaele, covering Ostend.

Early the next morning we marched into Ostend, and there received orders to entrain for a destination unknown. There are three stations at Ostend, and there were a large number of trains collected in the town; but the work of entraining a complete division, with all its horses, guns, transport, etc., was quite beyond the capacity of the Belgian railway authorities. No progress was made all day. Although there were plenty of trains, they were all mixed up in an inextricable mass in the various sidings, the Belgian station-masters running up and down the platform like rabbits.

It was not until late in the afternoon, when Sir Percy Girouard took over the entire arrangement of the train services, that there appeared any chance of our ever getting away. My brigade entrained from the main station in the middle of the town, and when the train arrived for the guns and wagons the station-master told us that we could start loading. It had not apparently struck the idiot that it was impossible to entrain guns and wagons off a platform unless ramps were prepared.

With great difficulty we managed to get hold of a Belgian company of Engineers and tried to show them how to make a ramp at the end of the platform so that we could run our guns and wagons on to the train from the end. When it was explained to them what was wanted they appeared to understand, and, after a considerable time, they produced two baulks of wood, about forty feet long and strong enough to bear many elephants. They had dragged these up from the docks. With enormous difficulty, and after great delay, they made a magnificent ramp at the end of the platform. There was then a space of about a yard between the last truck and the end of the ramp. On the train being backed to close up this yard, it gave the gentlest possible tap to the end of the ramp, which promptly collapsed on to the ground.

Our patience being now exhausted, we bundled the whole of the Belgians out of the station and took charge of matters ourselves. It was not long before the ramp was re-erected and properly secured, and the entraining proceeded rapidly. About three in the morning we got off in train loads carrying a battery each.

Early the following morning, the 10th, we stopped at a station and found that, after all our tribulations—forced marches, etc.—we had arrived back again at Bruges, the place that we had left so hurriedly forty-eight hours before. Here we found thousands of British sailors and marines who had escaped from Antwerp; but we were told that some four thousand British marines had been cut off and that we were to go on at once and try to relieve them. Our train, therefore, proceeded and took us on to Ghent.

On arriving at the station, we were met by a Staff Officer, who told us to get out of the train as quickly as we could, as the Germans were attacking the town on the far side.

It did not take us long to detrain, and we at once posted off through the streets and out of Ghent in the direction of Melle. We could hear the guns firing quite close. The 22nd Brigade took up a position at Melle, covering the crossings of the Scheldt and facing east. However, except for desultory firing on the part of the Belgian artillery, nothing exciting happened that day.

At nightfall we withdrew a mile and billeted ourselves in a deserted château. I went on ahead to arrange about accommodation for the brigade headquarters, and found the château in darkness and all the doors locked. I was certain, however, that it was occupied, as I had seen a light in one of the windows as I rode up the drive. After hammering on the door for a long time, a window was opened upstairs and a servant put out his head and asked what we wanted. I explained that a party of British officers wished to pass the night in the château. The man was very uncivil, and said that he was not going to open the door for English or French or Belgians. I then addressed him in somewhat violent German, which he understood, and told him that, far from being French, British, or Belgians, we were the advance guard of the German Uhlans. This frightened him thoroughly, and he made great haste to open the door and place everything at our disposal. Our servants installed themselves in the kitchen, and soon a quite decent dinner was ready.

We had just finished dinner and were settling down for the night, when a terrific rifle fire broke out from the trenches immediately in front of us. This was our first experience of heavy firing, and most alarming it was in the darkness. The firing appeared to roll up and down the lines, sometimes dying down to a solitary shot, at other times being a continuous roar.

Gone were our visions of a comfortable night. Food baskets were packed up, horses saddled, and the brigade stood to arms. It was a very cold night, though fine, and we passed the remainder of the hours of darkness sleeping alongside the road with our horses' bridles through our arms.

In the morning we discovered that what had happened was as follows: The Germans had attacked the French sailors, who were on our left, more with the intention of finding out where they were than with any idea of assaulting, and had without difficulty been driven back. The French pursued the Germans with the bayonet and advanced some hundreds of yards in front of their position. Unfortunately, in returning to their trenches they did not return quite the way they came, and retired at an angle which brought them across the front of the Warwickshire Regiment, who were our left. This regiment, hearing advancing troops on them in the darkness, naturally assumed that they were Germans, and opened fire on them. The French sailors, who by this time had apparently lost all sense of direction, imagined that they were being attacked by Germans. Hence the terrific battle which disturbed our night's rest. Before the mistake was discovered many thousands of rounds must have been expended on both sides, and I regret to add that the total casualties were one man of the Warwickshires, who was slightly wounded in the foot.

Before dawn next morning (the 11th) we returned to our positions, and no sooner had we occupied them than two batteries of Belgian artillery trotted up on our flank and immediately started firing. We inquired of the Belgian officers what they were firing at, and were told “nothing.” This struck us as peculiar, and, on asking the reason, we were told: “We always fire in the early morning and late in the evening just to let the Germans know we are there.”

All that day we remained in our positions, expecting to be attacked. We had no idea what force was in front of us, but it was variously estimated as being a few battalions of the German advance guard or several Army Corps. As a matter of fact, I believe that there were practically no Germans at all near us.

In the course of the morning we captured three prisoners, who were brought before me to be examined. I ascertained that they were men of the Landwehr, and that they belonged to a division which had just arrived from Antwerp. They had been lost in a wood during the previous night attack, and were very willing to tell me all they knew, but this did not amount to much. The quartermaster-sergeant of the brigade brought me a document which had been given to him that morning by a Belgian soldier. It was carefully sewn up in waterproof cloth and had been found in the lining of a German's tunic. It was very badly written, but, with the assistance of another interpreter, we managed to decipher it. It turned out to be a long and rambling account of an episode that happened in 1746, to the effect that a certain German count, having lost his temper with his servant, ordered him to be beheaded. The executioner duly tried to cut off his head, but the sword refused to cut. This surprised the Herr Graf, and he asked the culprit how it was that he was immune from the sword. The man replied that if the count would spare his life he would tell him his secret, which consisted of a number of cabalistic words. The count, being much interested, spared the man's life and ordered many copies of this formula to be written out and distributed among his people. Evidently the unfortunate German soldier of 1914 had hoped that the carrying of this talisman would protect him also.

That evening I believe there was a conference between General Rawlinson, General Capper, the Belgian Commander, and the French Admiral, who was in supreme command of this expedition. Our movements so far had not inspired any of us with great confidence, and it was decided that, Antwerp having fallen and the greater majority of our sai...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- THE WAR DIARY OF THE MASTER OF BELHAVEN

- Copy of Telegram