![]()

CHAPTER I — INTRODUCTION

The idea of utilizing railroads in the defense of the United States was not a new concept that blossomed with the Civil War. As early as 1828, both military leaders and several politicians recognized the importance of rail transportation as a means of rapidly moving large bodies of troops to threatened areas on the eastern seaboard. For reasons of politics and money, these visionaries were thwarted in their efforts to build an integrated rail network that could be used for the defense of the nation. It was not until the Civil War that railroads came into their own as an important part of the national defense for America.{1}

With few exceptions, historians view the American Civil War as the first modern conflict. Advances in technology, mass armies, command and control systems, and civil-military relations all lend credence to this conclusion. Without a doubt, the Civil War was the first war in which the railroad made a significant contribution to the outcome of the conflict. In Civil War historiography, both the participants in the conflict and the later historians have agreed that the railroads were a significant factor in the conduct of the war, with consensus occurring on the contention that Northern railroads were better built, managed, and supplied than their Southern counterparts. In addition, it is accepted that for a variety of reasons the Southern railroad system fell apart between 1861-1865, and was unable to help bring victory to the Confederacy.

These two facts appear to contradict another widely held belief concerning strategy and the definition of interior lines as espoused in the United States Army Manual 100-5: Operations. This belief is reflected in the contention that the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines throughout most of the war; and that in order for the South to win the war, it had to make use of its interior lines in order to concentrate its inferior manpower numbers against the North at strategic points.

One of the earliest examples of this perception about the advantage attributed to the fact that the South enjoyed interior lines is expressed by Matthew Steele and his early influential work, American Campaigns. Steele states,

“If we consider the whole vast theater of war from the Potomac to the delta of the Mississippi, the Southern armies had the advantage of interior lines. Never before in any of the world’s great wars would it have been possible to shift armies from one side to another of such a wide theater in time for sudden strategic combinations; but it was possible at this time by means of the railways within the Southern lines.”{2}

This belief continues to be expressed throughout Civil War historiography. Noted historians of Southern railroads, Robert Black and Angus Johnston, both maintain that the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines until late 1864, even though they both do an excellent job of describing the disintegration of the Southern rail network. Both authors looked at the question from a purely geographical point of view but failed to take into account the effects that technology had on time-space relationships. This view of interior lines is still widely reflected in more recent scholarship as the accepted view. It is espoused by such noted historians as Edward Hagerman, George Turner, James McPherson, Shelby Foote, Steven Woodworth, T. Harry Williams, Richard Beringer, and Archer Jones.{3} All of these historians give the advantage of interior lines to the South. Archer Jones went so far as to say that the South actually made excellent use of interior lines on a strategic level, with strategic concentration being achieved at both Shiloh and finally at Chickamauga. Jones faults Southern generalship as throwing away the advantage of interior lines in these instances of strategic concentration.{4} Woodworth also points out that strategic concentration was the only strategy for the Southern cause that had a chance of succeeding. He blames the Southern political leadership for not implementing the strategy, specifically criticizing Jefferson Davis. T. Harry Williams, like Jones, believed that generalship was the major factor in explaining why the South lost the war; yet he came closest in recognizing technology as a factor affecting interior lines when he criticized Confederate General Robert E. Lee in this manner: “He does not seem to appreciate the impact of railroads on warfare or to have realized that railroads made Jomini’s principle of interior lines obsolete.”{5}

Williams’ statement, ignored by the rest of the historical community, both clears up and muddies the view of the importance of technology and its impact on the traditional view of interior lines. For the first time Williams posited that technology could overcome a physical disadvantage. Yet Williams’ statement also begs several questions that he failed to address. Did the South ever have the advantage of interior lines? At what point in the war did the South lose the ability to move large bodies of soldiers between the eastern and the western theaters? Were there technological differences between the Northern and the Southern rail networks, and if so, what effects did the differences have upon the strategic movements of large bodies of troops?

These questions are important to historians who believe that the Confederacy had a chance to win the Civil War through the use of strategic concentration, or at least in prolonging the war until peace on Southern terms was attained. These questions require not only a strictly military and physical look at Southern railroads, but also a focus on the political and social fabric of the Confederacy and raise doubts about its ability to use all available assets. In other words, in order to utilize its physical advantage of interior lines for strategic concentration, the South would have had to possess a rail system that would have allowed it to shift large bodies of troops faster than the North in order to achieve tactical numerical advantage at a decisive point. In addition, the South also needed to have the political and social strength to subordinate local and state concerns to the common national good, without compromising the laissez-faire business and state’s rights political doctrines that were central to its way of life.

There is no denying that the South made excellent use of interior lines at the theater level in order to minimize its manpower disadvantage. Numerous examples of this can be found in the Eastern theater, specifically in the First Manassas campaign and in the Seven Days campaign in which forces were moved from western Virginia and the eastern seaboard to re-enforce what was to become the Army of Northern Virginia. Prior to the battle of Shiloh, Confederate General Albert S. Johnston based his strategy for the western theater on the use of the rail line running from Memphis to Louisville to rapidly concentrate his forces that were garrisoning strategic points in Kentucky and Tennessee. However, because of a strategic plan that emphasized both cordon defense and theater self-sufficiency, the South was unable to capitalize on its tactical understanding of the use of railroads for concentration and failed to broaden that conceptual understanding to the strategic level.

Robert Black maintains that the South lost its advantage of interior lines by December 1864.{6} It is the contention of this author that at the outset of the war, the South did in fact enjoy the advantage of interior lines and utilized its advantage to achieve strategic concentration in the eastern theater to fight the battle of First Manassas. This was accomplished in spite of local jealousies and a rail system that exhibited flaws in transporting large bodies of troops and supplies effectively. In addition, the South also made excellent use of interior lines in order to concentrate troops from as far away as New Orleans and Florida under Albert Sidney Johnston to fight the battle of Shiloh, although the Southern rail network almost failed this test of moving troops to the threatened western sector. With the fall of Corinth on 30 May 1862 the South lost its advantage of interior lines and the ability to rapidly shift troops from the states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, and Mississippi to other regions.

Although Braxton Bragg’s successful movement of forces for his 1862 Kentucky Campaign was an inter-theater movement, it points to the severe difficulties that the loss of Corinth created for the Confederate high command. Instead of moving from Corinth, Mississippi, to Chattanooga, Tennessee, a distance of some 280 miles, Bragg had to move from Tupelo, Mississippi, through Mobile, Alabama, through Montgomery, Alabama, through Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee. This represented a total distance of almost 700 miles. Not only was the distance greater but there were four gauge changes and one steamboat connection that had to be coordinated in order to complete the movement.{7}

The South’s loss of the rail line running through eastern Tennessee and western Virginia in mid-1863, coupled with the physical deterioration of the rail network and a lack of centralized planning led to the loss of strategic interior lines as an advantage for the Confederacy for the rest of the war. In order to account for the South’s loss of the advantage of interior lines, one must examine the Southern rail network, the technology of these times, and the Northern rail network. Additionally, one must understand the changes in the Southern rail network as the war progressed with regards to speed and line-haul capability and compare that to the North’s system in order to understand that the South very early in the war lost the ability to move large bodies of troops rapidly between theaters. This view of the Southern rail network will also be juxtaposed with the views of the Confederate government and the major commanders to show that along with an inadequate rail system, the South was also hampered by a state’s rights doctrine which prevented the centralized control necessary to use its railroads most efficiently. Additionally, there was a lack of will among major army commanders, specifically Robert E. Lee, to use assets for strategic concentration due to mistrust in the rail system. These facts, coupled with local jealousies and a strategic outlook that dismissed the shifting of forces on the scale necessary to achieve overwhelming superiority at a decisive point, precluded the ability of the Confederacy to utilize the concept of interior lines effectively.

![]()

CHAPTER II — THE PRE-WAR RAILROAD NETWORKS IN THE NORTH AND THE SOUTH

The origins of the Southern railroad system that supported the Confederacy in the Civil War can be found in the rapid expansion that occurred during the 1850’s. During that decade, several factors influenced Southern railroad development: economic competition with the North for western markets; faulty centralized planning; geography; a small industrial base; little hard capital; and the individualistic Southern mentality. These factors combined to create a railroad system that did not integrate well into the existing Southern transportation network. While many Southern railroads were initially built to bring cotton and consumer goods to the rivers for transport to Southern seaports, many of the railroads that came into existence during the 1850’s, such as the Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad, were built to compete against the Southern river system. Therefore, instead of complementing the existing Southern river transportation network, many railroads duplicated existing transportation lines. While the Southern rail network was designed to turn a profit by transporting agricultural goods and passengers in peacetime, it was not designed nor was it able to meet the great demands placed on it during the Civil War.{8}

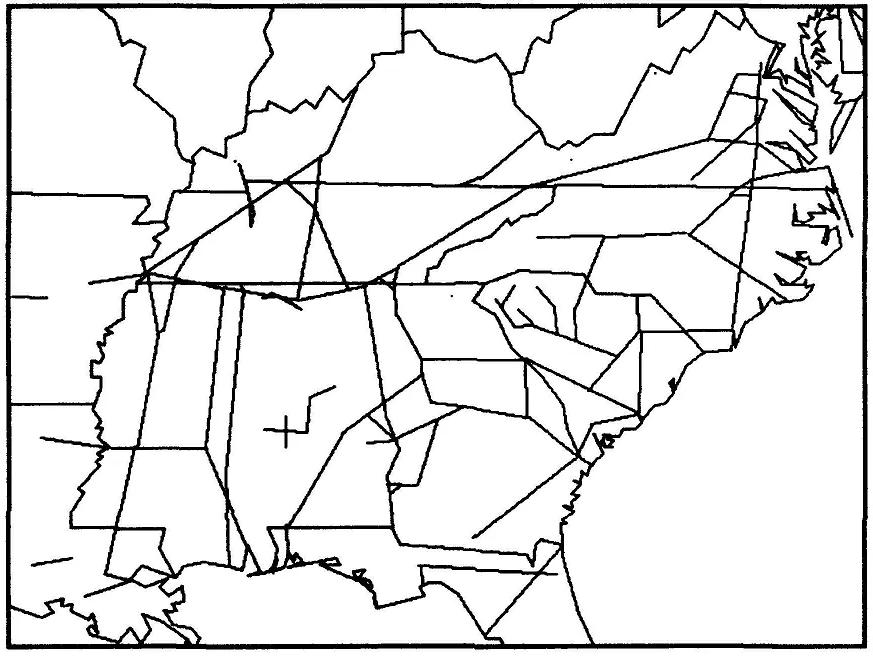

Figure 1: Southern Rail Net, 1861

In the decade prior to the Civil War, Southern railroad expansion increased fourfold from 2,309 miles of operating lines to 8,795 miles of operating lines, with almost two times that much planned. (See Figure l for the Southern rail network in 1861.) There were 155 main line railroad companies in existence along with 39 branch line companies.{9} The total net worth of these railroad assets in 1860 was $235,960,842.{10} In addition, this huge expansion occurred under very favorable circumstances. By 1860, Southern railroads were built at one half the cost per mile that it took to build Northern railroads. Further, there were only three railroad companies in the South that defaulted on their payments for a total loss of $2,020,000. In the North, eleven companies defaulted on loan payments during the 1850’s for a net loss of $39,000,000. {11} On most Southern lines dividends fluctuated between 8 and 10 percent.{12}

This impressive expansion was due in part to an impression among Southerners that the North was isolating the South by syphoning off its trade with the western states. By the end of 1860 four major east-west trunk lines operated, tying the Northern and western sections of the country together. Three of these lines ran through New York and Pennsylvania. The fourth ran through Maryland. Thus, when war came, there was not a single east-west through line that was totally in the South. By the mid 1850’s it was both cheaper and faster to ship agricultural goods from Memphis to the east coast using railroads than it was to ship them down the Mississippi river through New Orleans.{13} In addition, there was no north-south rail line that linked the Northern and Southern sections of the country together at the outset of the war.{14} By 1860, there were two rail lines under construction that would link the South and the West together, but neither had been completed by the beginning of the war. Because Southern railroad expansion was not aimed primarily at inter-sectional ties, the Southern railroad system tied the South together as a section, increasing the Southern output of cotton as a cash crop by opening the Southern interior to inexpensive transportation costs. Socially, the railroads offered a new outlet for the use of slavery in railroad construction thereby strengthening the South’s reliance on that form of labor.{15}

As early as 1850 J. D. B. De Bow, one of the foremost advocates of Southern industrialization, called for a convention on Southern railroad expansion, hoping to coordinate growth and centralize planning.{16} The first of several conventions was held in New Orleans in January 1852, and many leading railroad owners attended it.{17} De Bow called for a consensus on railroad development in the South to integrate construction and future expansion into a cohesive plan. For a variety of reasons, De Bow’s dream of a centralized Southern railroad net was never realized, even though in 1856 the Southern Railroad Association was formed to plan and coordinate future railroad construction.

In 1850, the majority of the Southern railroads ran north-south due to the topography of the region. Until the decade prior to the...