![Small Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3021622/9781782893608_300_450.webp)

- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Small Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition]

About this book

[Includes 11 illustrations and 6 maps]

The Guerilla Warfare in the jungles and paddies of Vietnam was unlike the previous wars that the United States had been involved in for the past hundred years; there were no frontlines, no rest areas, few uniformed enemies and a terrorized population unwilling to help. The tactics, strategies and experiences that would show the way forward were often developed by the small units; squads, platoons and outposts who saw the most of the hard fighting in isolated engagements with their elusive enemies. To ensure that this valuable resource of knowledge and experience was disseminated to all the men of the Corps, the Marine Intelligence department plucked Captain Francis J West Jr and sent him to join the 5th Marines on their day-to-day engagements, patrols and ambushes. What he learnt and recorded, frequently under fire, were the actual experiences of the USMC at the sharp end of the fighting during the Summer of 1966. Aimed at the men of the Corps he wrote of the tense ambushes, long range patrols, 15 second engagements, artillery support, airstrikes and even battalion level sweeps through the awful conditions of the war.

A vivid and visceral account of the struggle of the U.S. Marines during the summer of 1966.

The Guerilla Warfare in the jungles and paddies of Vietnam was unlike the previous wars that the United States had been involved in for the past hundred years; there were no frontlines, no rest areas, few uniformed enemies and a terrorized population unwilling to help. The tactics, strategies and experiences that would show the way forward were often developed by the small units; squads, platoons and outposts who saw the most of the hard fighting in isolated engagements with their elusive enemies. To ensure that this valuable resource of knowledge and experience was disseminated to all the men of the Corps, the Marine Intelligence department plucked Captain Francis J West Jr and sent him to join the 5th Marines on their day-to-day engagements, patrols and ambushes. What he learnt and recorded, frequently under fire, were the actual experiences of the USMC at the sharp end of the fighting during the Summer of 1966. Aimed at the men of the Corps he wrote of the tense ambushes, long range patrols, 15 second engagements, artillery support, airstrikes and even battalion level sweeps through the awful conditions of the war.

A vivid and visceral account of the struggle of the U.S. Marines during the summer of 1966.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Small Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition] by Captain Francis J. West in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

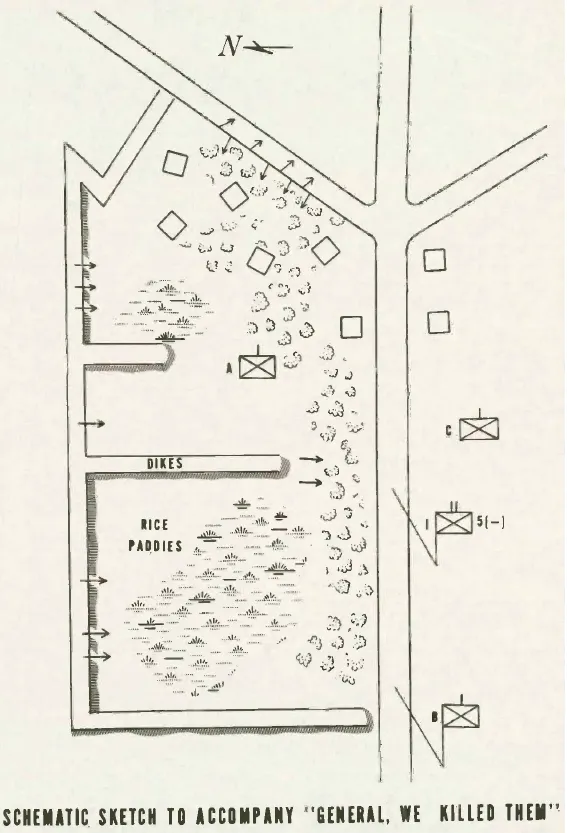

“GENERAL, WE KILLED THEM.”

Preface: At dawn on 11 August 1966, the author arrived by helicopter in 1/5’s perimeter, some 20 miles northwest of Chulai and 6 miles west of Tam Ky, a district headquarters near the South China Sea. On that perimeter 10 hours earlier, the battalion had fought the only major battle of Operation COLORADO. The author was well acquainted with the officers and men of the battalion and so, gathering in large groups, they told him in detail what had occurred and pointed out the exact positions they had held. He wrote the somber aftermath from personal observation.

I — ENCOUNTER FOR ALPHA COMPANY

After his companies, searching separately for the elusive enemy during the first few days of Operation COLORADO, had met no hard resistance. Lieutenant Colonel Hal L. Coffman had consolidated his 583-man battalion (1/5) and was sweeping toward the sea, some seven miles to the east. For three consecutive days, the route of the battalion lay along a dirt road which wound through valleys out of the foothills of scrub-covered mountains and east across monotonous expanses of fiat land stretching to the sea in an unbroken succession of rice paddies tree lines, and hamlets. The troops had uncovered little evidence to indicate the presence of a large enemy force, but each day it seemed they saw fewer villagers, while the intensity of sniper fire increased.

On the morning of 10 August, the enemy snipers were unusually persistent. All three rifle companies—Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie—encountered small groups of snipers every few hundred meters along the route of march. Enemy snipers in Vietnam are like hornets. If ignored entirely, they can sting. But if reaction is swift and aggressive, they can be swatted aside. Responding aggressively, the Marines poured out a large volume of fire each time they were fired upon. The snipers, however, carefully kept their distance, rarely firing at ranges closer than 500 yards. (The previous day a few North Vietnamese had waited until the Marine point squad was within 200 meters before firing. Those enemy soldiers had been pinned down, enveloped, and dispatched.)

Coffman and his company commanders did not like the situation; the troops were expending ammunition at a rapid rate with no telling effect upon the enemy. Toward noon, they ordered the squad leaders to supervise very selective return of fire in order to conserve rounds. Marching under a clear sky and searing sun, Coffman knew the helicopters could resupply his battalion but disliked making that request if not solidly engaged.

At approximately 1100, the battalion arrived at the hamlet of Ky Phu. Coffman called a halt and the men settled down in what shade they could find and began opening C rations. Shortly thereafter, word was received for 1/5 to remain in position pending the arrival of the regimental commander, Colonel Charles A. Widdecke.

After a conference with Colonel Widdecke, Coffman issued the order to push forward again. At 1400, the battalion resumed the march with the hamlet of Thon Bay as its objective.

All indications were that the battalion would reach Thon Bay about 1600. Coffman liked to allow himself ample time to set in before dark. It took a few hours to tie in the lines of a battalion properly and on previous days he had allowed several hours for the task.

As they had on previous days, the companies guided on the main road which led to the sea. In front of the Marines lay acres of rice paddies gridded by thick tree lines and tangles of scrub brush, familiar enough landscapes. Groves of palm trees and patches of wooden huts dotted the roadside. Storm clouds were billowing over the mountains to the west behind the Marines.

Charlie and Alpha Companies, forming a dual point, struck off together, covering respectively the right and left flanks of the road. Both companies spread out far across the paddies.

In trace along the road followed the battalion command group, consisting of the 81mm mortar platoon, the battalion headquarters, the 106mm recoilless rifle platoon (without their antitank guns), the logistics support personnel, and others. Bravo Company brought up the rear. The battalion was thus spread in a wide “Y” formation, the stem anchored on the road and the prongs pushed well out in the paddies.

Upon resuming a march, a battalion commander can generally expect a time lag of several minutes caused by a few false starts as squads, platoons, and companies jerk and bump along before sorting themselves out and hitting a smooth, steady pace. This did not happen on the afternoon of 10 August. The battalion moved swiftly. The platoons at point fanned out on both sides of the road. Slogging through paddies and twisting through tree lines, they covered more than a mile in the first 20 minutes. Rain was washing away their sweat and impeding their vision when they arrived at the outskirts of the tiny hamlet of Cam Khe at 1510. They noticed that the huts they passed were empty. Nor were there any farmers working in the rice paddies. Giving cursory glances into dugout shelters and caves, the Marines saw that they were packed with villagers.

Because of this fact, the men were alert and wary when they passed through and around the hamlet. As the 2d Platoon, Alpha Company, pushed through the scrub growth on the left flank of the hamlet, the men saw to their front a group of about 30 enemy soldiers cutting across a paddy from left to right. The platoon reacted instinctively. The men did not wait to be told what to do. Throwing their rifles to their shoulders, they immediately cut down on the enemy. Their initial burst of fire was low, short, and furious. Caught in the open, moving awkwardly through the water and slime, the enemy could not escape. Shooting from a distance of less than 150 yards, the 2d Platoon wiped them out in seconds. Farther back in the column, men thought a squad was just returning fire on a sniper. Although they did not yet know it, the battle which the Marines had sought was joined. The Marines had struck the first blow, and it had hurt.

The North Vietnamese, however, counterpunched hard. From a small hedgerow behind the fallen enemy, several semiautomatic weapons opened up and rounds cracked by high over the Marines’ heads. The troops were now keyed for battle. Excited and stirred by their swift, sharp success, the platoon shifted its direction of advance and splashed into the paddy. The volume of enemy fire increased and bullets spouted in the water around the Marines. The platoon’s momentum slowed as the Marines started flopping down into the water to avoid the fire. But no one had yet been hit, and the platoon quickly built up a base of fire and continued the movement by short individual rushes.

The company commander, Captain Jim Furleigh, came up, bringing with him the 1st Platoon. That unit in turn rushed into the paddy on the left flank of the 2d Platoon. The volume of enemy fire was swelling. With 70 bulky, slow-moving targets to hit at close ranges, the enemy gunners improved their air as well.

Almost in the same second, a man in each platoon was struck by machine gun bullets. Other Marines stopped firing to help the wounded men or merely to look. The rate of outgoing fire dropped appreciably. Encouraged by this, the North Vietnamese redoubled their rate of fire. No longer forced to duck low themselves, they aimed more carefully and bullets hit more Marines lying in the water. The machine gun in the tree line in front of the 2d Platoon chattered insistently, traversing back and forth in low, sweeping bursts over the Marines’ heads. Two more Marines were hit. The men ducked low and, not wishing to expose themselves, fired even less in return. The attack had bogged down.

The 2d Platoon had advanced 40 meters across the paddy; the 1st Platoon not more than 20. In the tree line 100 meters away, they could see the North Vietnamese moving into better firing positions, most wearing camouflaged helmets and some clad in flak vests. The Marines could find no cover or concealment in the paddies and time was running against them. The machine gun had them pinned; the rain and mud and their heavy gear prohibited a quick, wild, surging assault. Furleigh, a sharp-eyed, quick-minded West Point graduate, assessed the situation. As he saw it, there were two alternatives: to go forward or back. What he would not do was let the company stay where it was. He thought if he urged the men, they would go forward by bounds again until they carried the enemy tree line. But casualties from a frontal assault against the effective machine gun emplacement would be heavy. Even as he pondered the dilemma, three more of his men were hit. That clinched it for him. He decided to pull back; at least that way he thought his people would escape the heavy fire and there would be time for the situation to clear and battalion to issue specific orders.

What Furleigh did not realize at that particular moment was that heavy fighting was raging in half a dozen other places, including the battalion headquarters. While Company A was attacking in the paddy, mortar shells had fallen along the road, just missing the battalion command group. The headquarters element, quite distinguishable with its fence of radio antennas, had hastily sought the concealment of the bushes and houses to the left of the road. The NCOs yelled at their sections to disperse yet stay close, and the radio operators tried to copy incoming messages and transmit at the same time. The officers were busy trying to pinpoint their position and decide on a «nurse of action, when everyone was taken under small arms fire coming from all directions. Reports filtered in by runner and radio that Alpha Company to the northeast was pinned down and withdrawing and that to the west, at the rear of the battalion, Bravo Company was battling. To the east, on the right side of the road, Charlie Company reported it too was engaged

In that situation, the battalion commander could not determine precisely the size or the nature of the engagement. No one could. (It probably would have been of some solace to Coffman if he had known then, as he did later, that the enemy were also caught off balance by the sudden engagement.) The headquarters group was busy defending itself. It was teeming rain in such heavy sheets that at times figures only yards away were blotted out. The visibility ceiling for aircraft had dropped to 50 feet, so no jet or helicopter support was available.

Coffman stayed calm. His was a seasoned battalion which he had commanded for 12 months. He knew his company commanders well. Faced with a battle which denied tight central control, lie let his junior officers direct the fighting while he concentrated on consolidating the battalion perimeter as a whole and shifting forces as the need arose.

The situation was terribly confused. Although the battalion was on the defensive, the individual units were on the offensive. Platoons from each company were attacking separate enemy fortified positions. Caught in an ambush pushing at his left flank, Coffman wanted to draw the battalion in tight. In attempting to consolidate, the companies had to fight through enemy groups. To relieve pressure on units particularly hard pressed, Marines not personally under fire moved to envelop the flanks of the North Vietnamese. The extraction of wounded comrades from the fields of fire—a tradition more sacred than life—was accomplished best by destroying the North Vietnamese positions which covered the casualties. So isolated were the fragments of the fight that each action is best described as it happened—as a separate event. Fitted together, these pieces form the total picture of a good, simple plan which was aggressively executed, with instances of brilliant tactical manoeuvres occurring at crucial moments.

By reason of extremity, Furleigh’s Alpha Company played the key role in the fight during the initial hour. From the very beginning, they were in the thick of it. Private First Class Larry Baily, a mortarman assigned to company headquarters, had moved up with his company commander. The way he described it: “The VC were everywhere. They were in the banana trees; they were behind the hedgerows, in the trenches, behind the dikes, and in the rice paddies.” Pulling back out of the paddy had not proved easy. Several Marines had been wounded, and one more killed, bringing to a total of five the number of American dead in the paddy. Displaying excellent fire discipline, the North Vietnamese singled out targets and concentrated a score of weapons on one man at a time. That unified enemy fire altered the exposed positions of some Marines from dangerous to doomed,. Those already rendered immobile by wounds were most vulnerable to sustained sniping. These casualties (among them Baily) had to be immediately moved from the beaten zone of the bullets.

It was an arduous movement. No man could stand erect in that storm of steel and survive. So the wounded were dragged along through the flooded paddies by their comrades, much like an exhausted swimmer is towed through the water by a lifeguard. Those not dragging or being dragged returned fire at the enemy. No one later felt that fire had inflicted more than one or two casualties on the enemy. But it was delivered in unslacking volume and that disconcerted the enemy gunners and forced them to snapshoot hurriedly. Had the platoons not reestablished a steady stream of return fire, it is doubtful they could have extricated themselves, keeping their squads and fire teams intact and taking their wounded with them. By repeated exhortations, curses, and orders, Furleigh provided the guidance necessary to steady the men and prevent any slackening of fire in the moments of confusion.

Once the two platoons had reached the hedgerow, they spread out to form a horseshoe perimeter with the 1st Platoon to the left of the 2d Platoon. The open end of the horseshoe faced southwest (toward the battalion command group), and the closed end faced the enemy to the north. Furleigh tried to call artillery fire down on the enemy. In the full fury of the thunder-and-lightning storm, the adjusting rounds could not be seen or heard. Nor did anyone in Alpha Company have a clear idea where the front lines of the other companies were. For fear of hitting friendly troops, Furleigh cancelled the mission after the first adjusting rounds had gone astray.

Conspicuously absent from the battle at this crescendo was the mighty fire power of supporting weapons, proclaimed by some critics as the saving factor for Americans in encounters with the enemy. The North Vietnamese had numerical and fire superiority. Initially, it was they who freely employed supporting arms, namely mortars and recoilless rifles. What had developed for Alpha Company—and for the battalion—was a test of its riflemen.

They responded magnificently. Once tied in, the two platoons of Alpha Company needed no urging to keep fire on the enemy. At first there was an abundance of targets to shoot at, since the North Vietnamese kept leaping up and darting about from position to position. The Marines, lying prone and partially concealed in the undergrowth, put out a withering fire. They could see enemy soldiers, when hit, jerk, spin, and fall. The men shouted back and forth, identifying targets and exclaiming at their hits. They were getting back for their frustration in the paddy.

Losing in a contest of aimed marksmanship, the North Vietnamese pulled a 60mm mortar into plain view and aimed it at the opposite hedgerow. While they were popping shells down the tube, the Marines who could see the weapon were screaming:

“Give us a couple of LAAWs—LAAWs up!” Several of the short fiberglass tubes were passed forward, thrown up from man to man. Some, after their long immersion in the water, failed to function. But others did and a direct hit was scored on the mortar.

While their attention was concentrated to the fron...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- MINES AND MEN

- HOWARDS HILL

- NO CIGAR

- NIGHT ACTION

- THE INDIANS

- TALKING FISH

- AN HONEST EFFORT

- A HOT WALK IN THE SUN

- “GENERAL, WE KILLED THEM.”

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

- GLOSSARY