- 90 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

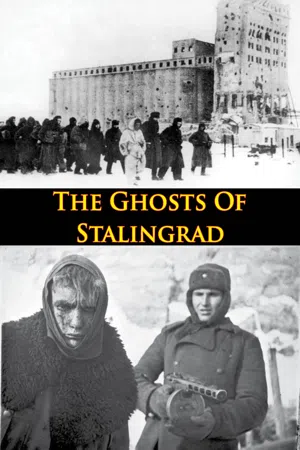

Ghosts Of Stalingrad

About this book

The Battle of Stalingrad was a disaster. The German Sixth Army consisted of over 300,000 men when it approached Stalingrad in August 1942. On 2 February 1943, 91,000 remained; only some 5,000 survived Soviet captivity. Largely due to the success of previous aerial resupply operations, Luftwaffe leaders assured Hitler they could successfully supply the Sixth Army after it was trapped. However, the Luftwaffe was not up to the challenge. The primary reason was the weather, but organizational and structural flaws, as well as enemy actions, also contributed to their failure.

This thesis will address why the Demyansk and Kholm airlifts convinced the Germans that airlift was a panacea for encircled forces; the lessons learned from these airlifts and how they were applied at Stalingrad; why Hitler ordered the Stalingrad airlift despite the logistical impossibility; and seek out lessons for today's military. The primary reason for the Stalingrad tragedy was that Germany's strategic leadership did not apply lessons learned from earlier airlifts to the Stalingrad airlift, and the U.S. military is making similar mistakes with respect to the way it is handling its lessons learned from recent military operations.

This thesis will address why the Demyansk and Kholm airlifts convinced the Germans that airlift was a panacea for encircled forces; the lessons learned from these airlifts and how they were applied at Stalingrad; why Hitler ordered the Stalingrad airlift despite the logistical impossibility; and seek out lessons for today's military. The primary reason for the Stalingrad tragedy was that Germany's strategic leadership did not apply lessons learned from earlier airlifts to the Stalingrad airlift, and the U.S. military is making similar mistakes with respect to the way it is handling its lessons learned from recent military operations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ghosts Of Stalingrad by Major Willard B. Atkins II in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 — INTRODUCTION TO THE LUFTWAFFE AND AERIAL RESUPPLY

“I have done my best, in the past few years, to make our Luftwaffe the largest and most powerful in the world. The creation of the Greater German Reich has been made possible largely by the strength and constant readiness of the Air Force. Born of the spirit of the German airmen in the First World War, inspired by faith in our Führer and Commander-in-Chief—thus stands the German Air Force today, ready to carry our every command of the Führer with lightening speed and undreamed-of might.”{1}—Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force: 1933 to 1945

Before the onset of World War II, Germany faced the daunting prospect of building an air force that, owing to the restrictions placed upon it by the Treaty of Versailles, was in an embryonic state. Having been forced to make concessions at the end of World War I that limited the size of its army and navy and prohibited it from maintaining an active military airpower, Germany was not in an enviable position. General Hans von Seeckt argued vehemently that Germany should be allowed to maintain an independent air force of 1,700 aircraft and 10,000 men. He was unsuccessful. Nevertheless, due to his foresight and vigilance, Germany succeeded in securing a cadre of experienced aviation officers who remained hidden within the staffs of the army and navy. This cadre kept the ideas of a strong, resurgent air force resonating throughout the interwar period. Under the direction of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, one of Adolf Hitler’s most trusted advisors, Germany was able to create a viable, aerial armada that would challenge Europe, Asia, and North Africa: the Luftwaffe. By 1940, the Luftwaffe was the biggest air force in the world.{2}

With the ascension of Hitler and the Nazi regime, Germany turned its thoughts toward mobilization and rearmament. A large portion of these efforts went into building military airpower. Because of the advances Germany had made in civilian aviation, its militarization was also within Germany’s reach. Like their British counterparts, the Germans felt the future of military airpower lay in the development of an independent bomber force. However, technological limitations and doctrinal disagreements between members of the Luftwaffe general staff, as well as demands upon the German Air Force in support of the German Army, stopped the strategic bombing effort before it got off the ground.{3}

German airpower doctrine consisted of several elements, noted historian Richard Muller, making it difficult to summarize. The Luftwaffe grew to maturity in the 1930s and was philosophically centered around the long-range bomber, but design problems with German aviation-engine technology and the needs of the army dictated otherwise. German airpower theorists of the era were aware that twentieth-century industrial societies were extremely vulnerable to aerial attack. As a result, much of the debate and theorizing between the wars revolved around the use of independent or strategic airpower. German Air Force officers, no less than their European and American counterparts, were ardent proponents of an independent bomber force. The airpower doctrine that eventually emerged in Germany was a hodgepodge of joint elements, with airpower utilized to support the other services, and independent strikes intended to destroy the enemy’s war economy or other centers of gravity.{4}

Germany’s geographic position focused the Luftwaffe on supporting the German Army. Germany did not have the advantage of some countries in terms of geostrategic position. Britain, for example, was situated so that strategic bombing would be the only practical way she could hope militarily to influence continental Europe; Germany did not have that luxury. Surrounded on two sides by perceived, if not real enemies, Germany’s focus on airpower was more geared toward combined-arms warfare and support of the German Army.{5} In fact, Hitler’s foreign policy stated that only France and Poland were potential enemies.{6} With these adjacent, putative enemies, there was no need for a true long-range, strategic bomber, and no need to focus on developing a doctrine for deep, strategic attacks. If war was to break out, Germany’s position within the hub of the European continent meant that she was not in any position to ignore the demands of the army. Doing so would put Germany at a distinct disadvantage. As a result, the Luftwaffe directed a majority of its energy to the army’s support.{7} Since the army was by far the larger and more important of the military services, the primary task of the German Air Force would be to support its maneuvers: the Luftwaffe could achieve this by destroying enemy troop concentrations, strong points, and lines of communication.{8} This utilitarian application of airpower was the result of extensive study and institutionalization of the tactical and operational lessons of World War 1.{9} In addition to bombing and other types of destructive activities, the Luftwaffe also contributed a great deal to the rapid mobility and supply of the Wehrmacht. The need for airlift to successfully execute these military operations is axiomatic.

The transport aircraft, mainly Junkers 52s and Heinkel 111s, enabled the Luftwaffe to keep pace with German Army advances, and later with its retreats. According to Asher Lee, a fleet of several hundred transport aircraft was always available to continue operations. Bombs, troops, fuel, spare parts, ground staff, and other equipment could be moved within twenty-four hours to occupy and operate from advance landing grounds, which they may have been bombing only several days before. Transport aircraft were also used for medical evacuation as well as for flying equipment, fuel, and stores to forward troops, airdropping supplies to troops when necessary, and for hastening airborne or parachute troops to vulnerable points in the line.{10}

Germany’s participation in the Spanish Civil War taught them many lessons about the application of airpower.{11} From July 1936 until April 1939, Adolf Hitler assisted General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War. During this operation, twenty Junkers Ju-52s ferried 10,000 Moroccan troops, as well as the Spanish Foreign Legion and their equipment from Tetuan to Spain in a ten-day period, enabling Franco to consolidate forces and establish a firm position to launch an offensive against the government.{12} This was the world’s first large-scale airlift operation.{13} Hitler remarked on this accomplishment in September 1942, “Franco ought to erect a monument to the glory of the Ju-52. It is this aircraft that the Spanish revolution has to thank for its victory.”{14} It is perplexing that Hitler and the Luftwaffe never realized the advantages of a large, modern, and robust airlift fleet for the mobility and long-term success of their own military until it was too late.

One of the foremost reasons behind Hitler’s willingness to support Franco’s cause was to test Germany’s new military equipment. This testing validated the strategy and tactics that had been developed in Germany. As a result, the Luftwaffe leadership entered the war confident that they had found both the means and the application to fulfill their objectives.{15} These discoveries greatly contributed to the fiscal resources Hitler gave to his air force.

Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe suffered from fiscal constraints as did the other services. However, there were two reasons that allowed the German Air Force to secure its necessary financing. First, Hitler had great confidence in airpower. He had seen the aircraft circling over the front lines of WWI and recognized their military value; to him the importance of possessing a strong air force was self-evident.{16} As a result, Hitler placed a strong emphasis on the Luftwaffe.{17} Second, the number two man in Hitler’s Nazi regime, Hermann Göring, was the Luftwaffe’s Commander-in-Chief. His position within the Nazi regime eased the struggle of obtaining the fiscal resources necessary to build a strong, efficacious air force. Göring’s immediate access to Hitler, along with the latter’s respect for his views on aviation matters, proved a priceless asset in the fight for the Reich’s precious financial and economic resources during rearmament, an asset which neither the Defense Minister, Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, nor the commanders-in-chief of the other two services possessed.{18} In addition to the fiscal limitations the Germans faced in the late thirties, Germany’s lack of natural resources also presented dilemmas to senior officials responsible for dividing these same materials to the industries that were expanding Germany’s military might. Despite Germany’s scarce resources, Hitler had a strategy for how he planned to achieve his goals, and his growing military was the centerpiece.

He hoped to create for Germany an “invulnerable” position in Europe and the world no matter how long it would take; in the German plan there was little concern for the destruction of industrial and war production.{19} His strategy was based upon overwhelming Germany’s foes with superior numbers and firepower, requiring huge increases in all the armed services. Interservice rivalry and competing interests for armaments created fierce competition for the Reich’s resources: iron, steel, copper, tin, rubber, oil, etcetera became increasingly scarce.{20} This paucity of natural resources, combined with an approach that called for overwhelming firepower in support of the army, made it nearly impossible for long-range, strategic-bombing advocates to galvanize others to their cause. To achieve their Führer’s objectives, all the Wehrmacht required was the support of combined-arms aircraft; as a result, Luftwaffe production reflected this need. Medium-range bombers, ground-attack aircraft, etcetera, were designed and built to support the army.

Despite Hitler’ assertions to the contrary, many German leaders never desired nor anticipated a protracted war. They envisioned quick, decisive military victories that obviated any potential necessity to destroy an enemy’s industrial base. Göring himself stated after the war that he was always against the invasion of Russia even though he was confident that the Luftwaffe was easily the master of their eastern adversary: “I knew that we could defeat the Russian Army; but how were we ever to make peace with them? After all, we could not march to Vladivostock!”{21} He only acquiesced due to Hitler’s insistence on the campaign. The Reichsmarschall’s reticence was ostensibly due to a presumption that such a campaign would never be decisively short. The desire for quick, decisive victories led the Germans to underestimate the number of aircraft and pilots necessary to secure Germany’s goals should a short campaign fail. The Luftwaffe’s leadership contributed to this underestimation. In particular the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, General Hans Jeschonnek, was stricken by the forlorn hope that a war with Russia would be brief, eliminating the need for long term planning; therefore, he possessed little interest in Luftwaffe training, concerning himself with the already available strategic-tactical force.{22}

The German Air Staff was fundamentally organized like any other air staff. Göring was at the top; Field Marshal Erhard Milch was his deputy, the Secretary of State, and the Inspector General; Jeschonnek his Chief of Staff; and General Ernst Udet was Chief of Aircraft Design and Supply. Göring had an operational staff which dealt with all major issues of policy and Luftwaffe organization, anti-aircraft defense, operations in the field, weather, intelligence, security, the German aircraft industry, etcetera. There was also a separate staff that dealt with administration and maintenance, once the operational policy was implemented. However, the Air Ministry exercised most of its control over fielded-units through a series of inspectorates, all under Milch. These were the link between fielded, operational units and the Air Ministry in Berlin, and ensured the former followed the policies of the latter.{23}

German leaders organized the Luftwaffe into geographic air fleets. There were four before the war with two more created as the war progressed to account for newly acquired territory (during German expansion). Number five was added to cover Denmark and Norway. In 1943 a sixth air fleet was created to handle the responsibilities of the Central Russian Front. Its headquarters was at Smolensk, but only briefly as the tide turned due to the Soviet army inexorably pushing the Wehrmacht back toward Germany.

Each German air fleet usually va...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ABSTRACT

- FIGURES

- CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION TO THE LUFTWAFFE AND AERIAL RESUPPLY

- CHAPTER 2 - DANGEROUS PRECEDENTS: DEMYANSK AND KHOLM

- CHAPTER 3 - STALINGRAD

- CHAPTER 4 - STRATEGIC DILETTANTISM

- CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

- SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY