- 458 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Memoirs Of Lord Ismay

About this book

"This memoir is a masterly narrative by a participant at the very centre of British decision-making during the entire Second World War. Major General 'Pug' Ismay was appointed secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence in July 1938 and from there became, in May 1940, Churchill's senior military assistant and an additional member of the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Officially, his role was the leadership of the office of the minister of defence. Churchill was by then both prime minister and minister of defence and continued in these twin roles throughout the war. Ismay saw himself as Churchill's 'agent' and was once flippantly described as his 'Eminence Khaki'. Ismay was in a unique position to observe Churchill, who became a close confidante.

Ismay has been praised by several highly-placed sources for his achievements in diplomacy and man-management during his Army service. His tact and charm kept the potential friction between the chiefs-of-staff and their political masters entirely controlled. His ability to ride the sometimes wild swings in Churchill's temperament, yet still bring to committees the correct interpretation and thrust of Churchill's views, was highly valued.

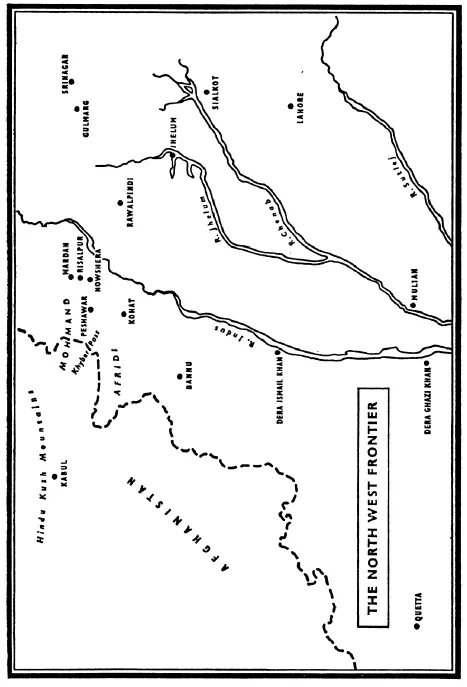

This book is a masterpiece of prose. It is a remarkable product of its time and is in no way self-indulgent. It lacks military jargon and acronyms. It is full of interesting and humorous anecdotes and provides an excellent account of many aspects of Churchill's non-public persona. It contains a single monotone plate of the author as well as three organisational diagrams and four maps. Not only military historians, but anyone with an interest in British history from the 1920s to the 1950s, would be greatly satisfied with it."—Bruce Short RUSI Journal

Ismay has been praised by several highly-placed sources for his achievements in diplomacy and man-management during his Army service. His tact and charm kept the potential friction between the chiefs-of-staff and their political masters entirely controlled. His ability to ride the sometimes wild swings in Churchill's temperament, yet still bring to committees the correct interpretation and thrust of Churchill's views, was highly valued.

This book is a masterpiece of prose. It is a remarkable product of its time and is in no way self-indulgent. It lacks military jargon and acronyms. It is full of interesting and humorous anecdotes and provides an excellent account of many aspects of Churchill's non-public persona. It contains a single monotone plate of the author as well as three organisational diagrams and four maps. Not only military historians, but anyone with an interest in British history from the 1920s to the 1950s, would be greatly satisfied with it."—Bruce Short RUSI Journal

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Memoirs Of Lord Ismay by General Lord Hastings Ismay KG GCB CH DSO PC in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE — APPRENTICESHIP

CHAPTER I — Subaltern in India — 1902-1914

On a July afternoon in 1902, a diminutive Carthusian of fifteen summers was practising at the cricket nets, when somebody shouted out that the results of the examination for senior scholarships had been posted up in the cloisters. He went there as fast as decency permitted — it would have been bad form to appear excited — only to find that the name ‘H. L. Ismay’ did not figure in the list. It was a bitter disappointment, because I had been consistently above at least four of the successful scholars for the whole of the past year; but I swallowed the lump in my throat and returned to the cricket nets feigning nonchalance. I did not realise at the time that my failure was a blessing in disguise.

When I was alone in my cubicle that night, I may or may not have shed a few tears, but I certainly did a lot of thinking. Ever since the South African War, I had had a sneaking desire to be a cavalry soldier; but my parents wanted me to go to Cambridge and try for the Civil Service. Now that I had proved such a duffer at examinations, my chances of passing were remote. If I were to fail, what could I do for a living? I would be too old to qualify for any other profession, and in those days commerce was not considered suitable employment for a gentleman.

The more I thought about it, the more sure I was that I wanted to have a try for the Army as soon as I was old enough. But there was plenty of time before a final decision need be made, and it was over a year before I unburdened myself to my parents. By an unfortunate coincidence, a letter from my housemaster reached them at almost the same time. ‘I have never got over your boy missing a scholarship,’ he wrote. ‘It is one of those exasperating miscarriages of examinations which happen often enough, but rarely in a form which can be estimated so exactly.’ This high assessment of my abilities might have ruined my plans, but my parents, bless them, let me have my way. My father was particularly upset at the idea of my joining the Indian Cavalry, and never tired of telling the story about the cavalry officer who was so stupid that even his brother officers noticed it. I wish that he could have lived long enough to know that it did not turn out to be so much of a dead end as he had feared.

In the summer of 1904, I passed the necessary examination without too much difficulty, and in the autumn I entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. The year as a gentleman cadet passed pleasantly enough. It toughened me physically, and I learned to drill like a guardsman, shoot with rifle and revolver, dig trenches, ride, signal, draw maps, do gymnastics and wear my clothes correctly. I also learned a smattering of military tactics, history and engineering. But so far as I remember, man-management and the art of command found no place in the syllabus. Sandhurst never meant nearly so much to me as Charterhouse had done. The course lasted only one year, and there were few opportunities for making new friends outside one’s own term in one’s own company. Many of my contemporaries were destined to be killed or crippled in the First World War and, partly for that reason, an unusually high proportion of them went to the top of the military ladder. Notable among these were Field Marshal Lord Gort, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Newall, Generals Platt, Gifford, Riddell-Webster, Franklin and Heath, and Air Chief Marshal Ludlow-Hewitt.

In those days there was keen competition for the Indian Army, and it was necessary to pass out in the first thirty or so to be sure of a vacancy. I had evidently improved at examinations, as I took fourth place and was gazetted a Second Lieutenant in His Majesty’s Land Forces on 5 August 1905. I was under eighteen-and-a-half years old and the smallest officer in the Army. Fortunately for myself — and my tailor — I grew six inches in the next two years.

Every officer destined for the Indian Army was required to serve a year’s apprenticeship with a British unit in India, and I joined the First Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment as an attached officer at Ambala in the Punjab, They were very considerate and took great pains to instruct me in the way that I should go. But I was never able to forget that I was a bird of passage, and that I was in the regiment, but not of it. Their scarlet uniform had white facings: mine had blue. They wore two badges in their helmets, one fore and one aft, in commemoration of a notable feat of arms in Egypt. My helmet had a single and not very attractive emblem. On one occasion towards the end of my year’s attachment, I was given the honour of being allowed to carry the Regimental Colour on a particularly long march. I received it with due deference; but it was an awkward burden, and at the end of twelve miles my thoughts were far from reverent.

When my year with the Gloucesters came to an end, there was no immediate vacancy in the Indian Cavalry Regiment which had accepted me, and I continued to be a ‘displaced person’ for nine more months. Six of them were spent with the 33rd Punjabis, a fine battalion which was practically annihilated at Loos in the First World War, and the remainder months with the Carabineers (6th Dragoon Guards) learning cavalry work.

It had been depressing to belong to nobody, and I was happy and hopeful when the day came for me to join what was to be my own regiment at Risalpur on the North-West Frontier. I had to travel half across India to get there, and arrived at the officers’ mess, unkempt and travel-stained, just as dinner was finishing. The scene is indelibly stamped on my memory. Eight or nine of my future brother officers in our magnificent mess kit of dark blue, scarlet and gold, were seated at the table. Behind them stood the waiters in spotless white muslin, with belts of the regimental colours and the regimental crest on their turbans. The table was decorated with two or three bowls of red roses and a few pieces of superbly cleaned silver. Over the mantelpiece hung a picture of our Royal Colonel, the late Prince Albert Victor,{1} and the heads of tigers, leopards, markhor and ibex looked down from the walls. The assembled company were all strangers to me, but they made me feel at home from the moment I crossed the threshold. As I went happily to sleep that night, I thanked God for parents who had allowed me to choose my own way of life.

***

I at once set to work to learn all about my new-found heritage. The full title of the regiment was the 21st Prince Albert Victor’s Own Cavalry (Daly’s Horse) Frontier Force. It had been raised by Lieutenant Daly in 1849 and had had a short but crowded history. Only twice had it left the frontier; the first time to take part in suppressing the Indian Mutiny in 1857; and the second to fight in Afghanistan in 1878. The Punjab Frontier Force to which the regiment belonged consisted of five regiments of cavalry, four batteries of mounted artillery and ten battalions of infantry, and was charged with the responsibility of guarding six hundred miles of turbulent frontier. Their duties of watch and ward have been faithfully described by Rudyard Kipling in one of those pen pictures of which he was a master. ‘All along the North-West Frontier of India there is spread a force of some thirty thousand foot and horse, whose duty it is quietly and unostentatiously to shepherd the tribes in front of them. They move up and down, and down and up, from one desolate little post to another; they are ready to take the field at ten minutes’ notice; they are always half in and half out of a difficulty somewhere along the monotonous line; their lives are as hard as their own muscles, and the papers never say anything about them.’{2} But let it not be thought that the units of the Punjab Frontier Force — or Piffers as they were nicknamed — were merely armed police. On the contrary, all their units were highly trained for all kinds of warfare, both in and out of India, and a proportion of them were invariably included in the organised expeditions which were launched across the Frontier in order to bring to heel this or that tribe. The churches and graveyards of Mardan, Kohat, Bannu, and the rest bore witness to the forfeits which they paid so proudly and so willingly. No soldier could wish to lie in more gallant company.

When the British left India in 1947, it was felt that perhaps these memorials to our comrades might not continue to be tended with the same loving care as in the past, and many of them were brought to England, together with the Communion plate from the churches on the Frontier. Thanks to the kindness of the ecclesiastical authorities in London, there is now a Frontier Force chapel in St Luke’s Church, Chelsea, in which we have our Book of Remembrance and other treasures; and the crypt below has been garnished as a shrine for the brasses and other memorials of our dead. Once a year a special service is held in the chapel, and is attended by an ever dwindling number of survivors, each one of us with memories of comrades, both British and Indian, who were true as steel, and of a brotherhood in arms whose glory will never fade. But I have anticipated.

The 21st Cavalry, like nearly all other Indian Cavalry regiments, was organised on what was known as the silladar system.{3} When it was first raised every recruit was required to bring his own horse, saddlery, sword and other equipment, and the only Government property issued to him was his musket. As a result, the horses were of every breed, size, colour and shape, and the equipment was of many different patterns. The regiment may have presented a moteley appearance, but there was never any doubt about its fighting value. After some years the system was modified in the interests of uniformity and efficiency. The recruit, instead of having to mount and equip himself, was required to pay a sum of about £50 to regimental funds. In return, he was provided, under regimental arrangements, with a horse, equipment and uniform throughout his service; and he was repaid his money in full when he was discharged. It seems odd in these days to think that there was a time when large numbers of youths were only too ready to pay a substantial sum of money for the privilege of serving in a profession which held out no hope of financial reward. But it must not be thought that all that was needed to become a member of the regiment was a bagful of silver. On the contrary, the competition for every vacancy was very keen, and the selection of candidates was carried out with the greatest care and formality. Other things being equal, preference was given to those with relations who were serving, or had served, in the regiment. No young man had any hope of being chosen unless he was related to or at least vouched for by a past or present member of the regiment, It follows that discipline was of a very personal kind. The Colonel was regarded as the father of a family, or perhaps the patriarch of a tribe, and the average trooper preferred almost any of the orthodox punishments to being told in public that he had brought disgrace on the regiment. Youthful delinquencies such as unpunctuality, inattention, sloppiness in deportment or dress were generally brought to the notice of one of the offender’s sponsors. We never knew what transpired, but the miscreant usually seemed chastened and repentant.

The 21st Cavalry, like the majority of Indian units, had a ‘mixed’ composition. Half were Hindus and half Moslems, but I cannot recall a single case of communal trouble, or even of communal prejudice. If, for example, we were called out in aid of civil power, the men never hesitated to act against their co-religionists with complete impartiality; it seemed as though all else was subordinated to their common devotion to the regiment and their pride in its traditions,

The story is told of a battalion whose Colours were shot to pieces in the unsuccessful assault on Bhurtpore in 1805. They were no longer usable, but when the day came for them to be destroyed with full ceremony, and replaced by new Colours, the British officers could find no trace of them. Thirty years afterwards the same battalion took part in a successful assault on the same fortress, and the mystery of the disappearance of the old Colours was cleared up. It transpired that they had been cut up by the men into a number of pieces, each of which had been carefully preserved as an amulet, and handed down from father to son. On the day that the disgrace of the defeat had been wiped out by victory, the fragments reappeared, were sewn together, and tied to the new Colours.{4}

To this tale of surpassing devotion, a personal postscript may be added. A Pathan officer, who was retiring after thirty-two years’ service, came to say good-bye to me on his last day with the regiment. He looked forlorn and I tried to cheer him up by saying that the peace and quiet of his home in the delightful vale of Peshawar would be very enjoyable after the hurly-burly of soldiering. He shook his head. ‘My grandfather was killed in this regiment in the mutiny,’ he said. ‘My father was killed in this regiment in the Afghan war. I was born in this regiment and have spent my whole life with it. I have a house in Peshawar, but my home is here.’ That evening I went to the railway station to see him off. All the Indian officers, Moslem and Hindu alike, were there and nearly all of them were in floods of tears.

The Indian officers were the link between the British officers and other ranks, and bore a great share of the responsibility for the tone of the regiment. Nearly all of them had done at least fifteen years’ service before getting their commissions; most of them had spent their lives on the Frontier; many of them had seen a good deal of fighting. But in the days about which I write, the standard of education left a great deal to be desired, and the senior Indian officer of my squadron, Dildar Khan by name, could not even sign his name. He was a beautiful horseman, had a good eye for country, had fought in three campaigns, and did not know the meaning of the word fear. For all his illiteracy, there was no better troop leader in frontier warfare in any army in the world. He often said that he prayed that he would be with me when I had my baptism of fire; and before long his prayer was granted. We were riding down a broad valley in Mohmand country when a sudden fusillade was opened on us from the crest of the hills. I looked round to see two or three saddles empty, and Dildar Khan gazing into my eyes as though willing me to do the right thing, I was tempted to retire to a knoll which we had just passed, but remembered Dildar Khan’s advice that at the beginning of a fight, before the men were warmed up, it was a good rule to go forwards rather than backwards, I led the troop at a gallop to some rising ground about three hundred yards ahead, and ordered dismounted action. The old warrior did not say a word, but looked rather like a proud father who has watched his son kick a goal in his first football match.

***

To anyone who was fond of horses and riding, life with a cavalry regiment on the Frontier was blissful. The day usually started with squadron or regimental training, and Drummer Boy, my recently acquired warhorse, would be brought to my door about a quarter of an hour before the parade was due to start. He was a picture to look upon with his coat of satin, and a lovely ride. But his sense of humour on those cold winter mornings was disconcerting. As soon as I was in the saddle, he used to let me know how well he was feeling and what fun it would be to put his master on the floor. Our progress towards the parade ground was unorthodox, undignified and uncomfortable.

He would start off by putting his head between his forelegs in the hope of snatching the reins out of my hand and thus obtaining more liberty. Then perhaps we would go sideways for thirty or forty yards, and when he was tired of that he would try plunging backwards. Nothing that I could say or do had any effect on his exuberance. Coaxing, cursing, and even a sharp slap were all useless, and the ridiculous pirouette would continue until the squadron came into view. Then and then only would he confide to me that his back was now nice and warm, that his saddle tickled him no longer and that it was time we settled down to serious business. For the rest of the morning he behaved impeccably and responded to the lightest touch of rein or leg. Sometimes it was a field exercise; sometimes we practised precision drill; sometimes the squadrons would manoeuvre against each other; but whatever form the training took, it was difficult to imagine how two or three hours could be spent more enjoyably, and I for one was always sorry when the parade was over.

The next function was ‘Stables,’ This too was instructive, and enjoyable in a different way. It was an ideal opportunity for British officers to get to know more about the men and horses for which they were responsible. As they passed down the line they could talk with each sowar{5} on every kind of topic. What was the news of his father or uncle or other regimental pensioner in his village? How were his crops going? His horse’s coat was staring: why not see what a little boiled linseed would do? The day was to come when I knew every man in the regiment by name and the individual characteristics of practically every horse; and a great deal of this information had been acquired at ‘Stables’ throughout the years.

Sometimes there was a little office work to be done; sometimes we had a rifle inspection or a kit inspection or an inspection of saddlery; sometimes either a British or Indian officer gave a short lecture on a variety of topics, such as horse management or musketry. By lunchtime the day’s work was over. Soldiering was not then the highly technical profession that it has become, and the afternoons were nearly always free to do whatever we wished. Most of us played polo three days a week, and schooled ponies on the other afternoons. In addition there were occasional race meetings at neighbouring stations, and rough shooting for all who wanted it. I could never help thinking, as I drew my admittedly meagre salary at the end of each month, that it was very odd that I should be paid anything at all for doing what I loved doing above all else.

Perhaps even more enjoyable than the common round was the occasional excitement of hunting a gang of raiders. Before I had been long at Risalpur, orders arrived during dinner one evening that C and D squadrons were to move as fast as possible to a number of specific points about twenty miles distant, in order to try to intercept a large raiding party from Mohmand country which had killed a policeman, looted an...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

- LETTER FROM SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

- PREFACE

- PART ONE - APPRENTICESHIP

- PART TWO - THE CRUCIAL YEARS

- PART THREE - ROLLING STONE