![]()

CHAPTER ONE — THE CREOLE

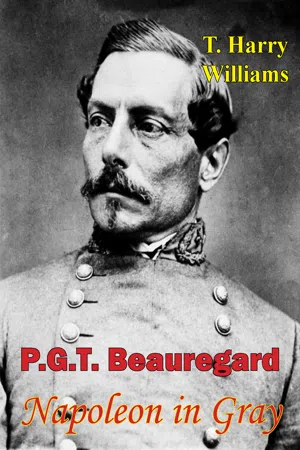

HE IS the most colorful of all the Confederate generals. He had more glamor and drama in his Gallic-American personality than any three of his Anglo-Saxon colleagues in gray rolled into one. The people of the Confederacy idolized him into a great popular hero, second not even to Lee. He was chivalric and arrogant in the best Southern tradition, but he was more. Something in his resounding name of Beauregard, in his Creole origin in south Louisiana, in his knightly bearing suggested a more exotic environment than the South of Jefferson Davis. A vague air of romance, reminiscent of an older civilization, trailed after him wherever he went. When he spoke and when he acted, people thought of Paris and Napoleon and Austerlitz and French legions bursting from the St. Bernard Pass onto the plains of Italy.

His military career was one of the most unique in the Confederacy and in many ways is more significant to the student of the Civil War than the record of any other Confederate general. It was not confined to one narrow area like Lee’s or interrupted by long periods of inactivity like Joseph Johnston’s or cut off before the end of the war like Braxton Bragg’s. Beauregard was in every important phase of the war from its beginning to its conclusion. He fired the opening gun of the great drama at Fort Sumter. He commanded the Confederate forces in the first great battle of the war at Manassas. In 1862 he was second and then first in command in the West; he planned and fought the first big battle in that theater at Shiloh.

From the West he went to Charleston, and there he conducted the war’s longest and most skillful defense of a land point against attack from the sea. In 1864 he returned to Virginia to direct the defense of the southern approaches to Richmond. Later in that year, the government assigned him to command the Division of the West, a huge department with an impressive title and few resources. In the waning months of the war, he was in Georgia and the Carolinas as first and then second in command trying to halt the onward rush of Sherman. He and Joe Johnston surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina the most formidable Confederate army left in the field after Lee yielded to Grant.

He saw most of the war to preserve the Old South. Then, after his cause crashed to defeat and the dream was ended, he was able to adapt himself to the ways of the New South. He was probably more successful than any other prominent Confederate general in making a living and accumulating wealth in the hard years after the war.

And that is why he became a forgotten man in the Southern tradition. When the Southern people made their bitter myths, they constructed them of sacrifice and poverty and frustration. The Southern hero was the reticent and reserved Lee, who lived modestly on a college president’s salary, or the grim Jackson, who fell gloriously on the battlefield and escaped having to face the realities of peace. In the Confederate legend there was small room for the prosperous Creole in gay New Orleans who ran railroads and, of all un-Confederate actions, presided over the drawings of a lottery company.

Just below New Orleans the parish of St. Bernard spread its fields of cane and corn, its cypress and live oak forests, and its dark swamps under the warm Louisiana sun. Frenchmen had settled it, and in 1818, only fifteen years after the cession of Louisiana from France to the United States, St. Bernard was proudly and even fiercely French. About twenty miles from the city, in the center of the parish, stood Contreras, the plantation home of the Toutant-Beauregards. Among the gentility of this region of Latin culture, the Toutant-Beauregards ranked high.

Jacques Toutant-Beauregard, the master of Contreras, could trace his French and Welsh lineage back to the thirteenth century. His grandfather, the first of the family to settle in Louisiana, had come out to the colony in the time of Louis XIV. Jacques numbered among his Louisiana ancestors Cartiers and Ducros, names of distinction in the bayou country. His wife was a De Reggio, another first family of St. Bernard. She had a family tree even more impressive than his. The De Reggio claimed descent from an Italian noble family, dukes no less, a scion of which migrated to France and founded a French line that eventually ended up in Louisiana.{1} Jacques could not know that the son who was born to him on May 28, 1818, the third child in what would be a family of seven, would eclipse the eminence of all the Toutant-Beauregards and De Reggios of the past. But he gave the boy a rich, ringing name to befit his ancient heritage. Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard. It would sound well in the future annals of fame. It would also always stamp its bearer as different outside of the bayou country. That sonorous appellation would stand out in the Confederacy like pompano en papillote in a mess of turnip greens.

Young Pierre grew up in an environment that was partly of the plantation South and partly unlike anything Southern. The home in which he lived was a large one-story house, not in the grand tradition of later plantation palaces but a mansion of aristocracy by the standards of its time.{2} The chief crop at Contreras was sugar cane, and there were slaves to plant and harvest it—and to wait on the wants of the white masters. Pierre played with slave boys his own age and as a baby was suckled by a Dominican slave woman. Like other Southern boys, Pierre hunted and rode in the woods and fields of his plantation and paddled his boat in its waterways.{3}

Except that Contreras produced cane instead of the familiar cotton and that he paddled on bayous instead of rivers, the physical features of his formative surroundings were typically Southern. The departure from the plantation pattern was in the cultural influences of his early years. Spiritually his family and south Louisiana were a part of France instead of the South. The Toutant-Beauregards were Creoles, Frenchmen of solid Old World backgrounds who had become feudal aristocrats in the New. They were Latins set down in a semitropical region of rich soil and lush crops that invited the establishment of slave labor. Their elite social position and their habit of commanding slaves made them imperious, proud, sometimes arrogant. They retained many Gallic traits and customs, modified only to suit the Louisiana scene. They loved merrymaking, lusty eating and drinking, luxurious living; they prized manners, breeding, tradition, honor—even to the point of absurdity.

To the American newcomers they seemed to be boastful posers who were also ignorant. They did strut and strike attitudes that were ridiculous to the Americans, and they did ignore, or affect to, the values of American culture. Being provincials, they felt superior to the parvenu Yankees, and at the same time they secretly worried that they were inferior. Feeling that their once-dominant social status was threatened by the incoming American horde, they guarded the old ways of their civilization with an aggressive vanity. They considered themselves cultivated Europeans living in a coarse new world. They might look to New Orleans as the city of their spiritual stimulation, but beyond New Orleans they looked to Paris. If New Orleans was their Paris, Paris was their Mecca.{4}

Pierre’s parents intended him to be a Frenchman. French was the language used at Contreras. He probably could not speak English until he was twelve years of age. When he was eight, his father sent him for three years to a private school near New Orleans where all the classes were taught in French. {5} Almost nothing is known of his life in these early years. He seems to have been quiet, studious, and reserved, almost the opposite of what he would be as an adult. Family tradition has preserved certain incidents which are assumed to have significance as revealing his later character. When he was nine, a man teased him before a crowd of relatives and friends, perhaps about failing as a hunter that day. Pierre seized a stick, chased his tormentor into an outhouse, and refused to let him emerge until he apologized. He accepted the apology but refused to shake hands. A little over a year later his mother took him to the Church of St. Louis for the children’s first communion. As he went up the aisle to the altar, a roll of drums was heard in the street outside. He stopped and looked back, and when the drums sounded again, to the horror of his mother he rushed out of the church. The second episode is supposed to show that even as a child he yearned to be a soldier. It probably meant only that as a country boy he was attracted by a loud and exciting noise. The outhouse story may have real meaning. He would always resent an affront and demand redress, but he seldom forgave.

When Pierre was eleven, his father decided to continue his education by sending him to school in New York City. It was something of a break with Creole custom for a boy to go to school anywhere except New Orleans or France, but the institution he was to attend had a safe Gallic background. Known in the East as the French School, it was operated by two brothers named Peugnet who had been officers under Napoleon Bonaparte. The curriculum emphasized mathematics and commercial subjects. Pierre stayed at the school for four years, coming home only in the Christmas and summer holidays. Here he learned for the first time to speak English, at least fluently, and to write the English language. He worked hard and made good grades in all his subjects. But more interesting to him than the classes were the tales the brothers were always telling of their service with Napoleon. Pierre listened with fascination. He began to read books about Napoleon and his campaigns. In his spare time at New York and during vacations at Contreras, he studied Jena and Austerlitz and all Napoleon’s battles. He had found a hero. For the rest of his life he would model himself on the great Corsican. He had also found a profession. Toward the end of his last year with the Peugnets, he came home and announced to the family that he wanted to be a soldier, an officer in the American army. He asked his father to get him an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.{6}

The family objected loudly. Even his father, who went further than most Creoles in associating with Americans, thought this was carrying collaboration too far. Pierre stood his ground. Nothing could change him once he had decided he was right. He would always be this way. He would never give ground on an issue of judgment. In the end the family yielded to his calm stubbornness. Jacques enlisted political influence to get his son entered at the military academy. Governor A. B. Roman wrote to Representative E. D. White, and White wrote to Secretary of War Lewis Cass to say that Pierre was a fine young gentleman who had been carefully educated and whose family had supported the American cause in the Revolution. The appointment came through almost immediately. Pierre was admitted to the academy as of March, 1834. Without waiting for his father to consent to the appointment in writing, a legal formality, he rushed up to West Point, possibly leaving from the Peugnet school. After arriving at the Point, he wrote Secretary Cass a letter of thanks which did not quite fulfill White’s laudatory remarks about his education: “I have written to my father to beg him to inform you weather he wished me to accept it or not; I will submit myself to the answer you will receive from him....I shall endeavour by my conduct during the period I will remain here to merit in some manner the bounty which my country [sic] to bestow upon me.”{7}

He enrolled as Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. The hyphen was dropped from his name and would never reappear. Family tradition has it that he deleted the Toutant to secure a better class rating by getting his name up among the B’s. This is highly improbable. A cadet’s standing at the end of each year was determined primarily by his conduct and grades. A more likely explanation is that! he realized the hyphen might subject him to ridicule from other students. The shortening of his name was part of the process by which he was Americanizing himself. In a few years he would lop off the Pierre and sign himself G. T. Beauregard.{8}

The school which the sixteen-year-old Beauregard was entering was the only officer-training institution of importance in the country. Most of the generals that he would fight with and against in the Civil War were the products of its classrooms. West Point was the best school of its kind that an aspiring officer could attend, but as a preparatory seminary for future generals it had glaring deficiencies. In the four years that a cadet spent at the Point he learned, or was given the opportunity to learn, a lot of mathematics, military engineering, and tactics. The curriculum literally bristled with courses in these subjects. The courses in general education were few in number and superficial in nature. Worst of all, there was little instruction in the higher nature of war—policy, strategy, and military history. Nor were students encouraged to study the theory of war on their own. The technical routine of the academy did not allow time for many visits to the library; and even if it had, the cadets could not have read the best works on war, for these were in French, and the French taught at the school was not sufficient to provide a reading knowledge. This handicap, of course, did not affect Beauregard, who read some of Jomini and learned some lessons he never forgot. In short, West Point turned out good tacticians and narrow specialists; it did not produce men who knew very much about the art of war.{9}

Cadet Beauregard was a grave, reserved, and withdrawn youth, the same kind of person he had been as a boy. Probably nobody at the academy really knew him. When men who had been his classmates tried in later years to recall what he was like, they could remember only that he excelled in sports, rode a horse beautifully, and made high marks.{10} Only one colorful episode was associated with his stay at the Point. He was supposed to have had a tragic love affair with the daughter of Winfield Scott, one of the senior generals of the army. According to the story, highly colored no doubt, he and Virginia Scott became engaged. Her parents insisted that they were too young to marry and that the engagement not be made public. The young couple parted; both wrote, but neither received the other’s letters. Beauregard, offended and embittered, soon married another woman.

Several years later he received a summons to come to Virginia on her deathbed. She told him that she had been grieved by his apparent inconstancy but had recently learned that her mother had intercepted his letters. Certain known facts make the tale partially plausible. In 1838, the year Beauregard graduated; Mrs. Scott took her seventeen-year-old daughter to Europe and was gone for five years. In France Virginia was converted to Catholicism. After they returned to the United States, Virginia, without her parents’ knowledge, entered a convent, where she died in 1845. Beauregard had married in 1841.{11}

There is no obscurity about his academic record. From the beginning he was an outstanding student. In the annual examinations given in June he stood among the five most distinguished cadets during his first three years, being fourth in 1835 and second in 1836 and 1837. He was also near the top of the conduct roll, with only three demerits in his first year, thirteen the second, and none the third. His teachers predicted a great future for him. He maintained his high position in his senior year. In the final listing of the class of 1838 at graduation, Beauregard ranked second in a group of forty-five. {12} Down the roll at number twenty-three was Irvin McDowell, whom Beauregard would defeat at Manassas in 1861 in the first important battle of the Civil War.

Beauregard also knew in his own class and in preceding classes several men who would serve under him in the...