![]()

CHAPTER I—IMPERIAL ARMY TO REICHSWEHR, 1918-1920

7 November 1918. Reichstag (Legislature) deputy Matthias Erzberger crossed the border into France and proceeded by car in search of Marshal Foch of France, the Allied Commander-in-Chief, who was designated to accept the German surrender. That a civilian was chosen to seek an armistice and end World War I is significant. By avoiding any participation in the armistice negotiations, the German High Command sought to shift the responsibility for the military defeat to Imperial Germany from the German Army and to convince the German people that the Army had not been defeated in the field. From this came the famous “stab-in-the-back legend.”{2}

9 November 1918. The last day of Imperial Germany. A general strike was called in Berlin and the workers were massing in the streets. The Naumburg Jäger, a trusted infantry detachment, mutinied and deposed its officers.

At 0900, Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg, Chief of the General Staff, spoke to a conference of divisional, brigade and regimental commanders (see Appendix I). Then, he and the First Quartermaster General, General Wilhelm Groener, left to see the Kaiser. {3}

As late as 8 November, both Field Marshal von Hindenburg and General Groener had felt they should continue to support the Kaiser, that he should not abdicate or flee the country.{4}

On 8 November, Admiral Paul von Hintze, the State Secretary at the Foreign Office, visited Field Marshal von Hindenburg and convinced the latter that the Emperor should abdicate his throne and leave Germany to save his life. Field Marshal von Hindenburg told General Groener of his change of feelings just prior to the 9 November commanders’ conference the ostensible purpose of which was to determine the loyalty of the troops. {5} In reality, though, Field Marshal von Hindenburg knew the Army was no longer a cohesive force. Torn between two conflicting loyalties to his Emperor, Field Marshal von Hindenburg addressed the officers only briefly without discussing the basic issue of troop loyalty.

![]()

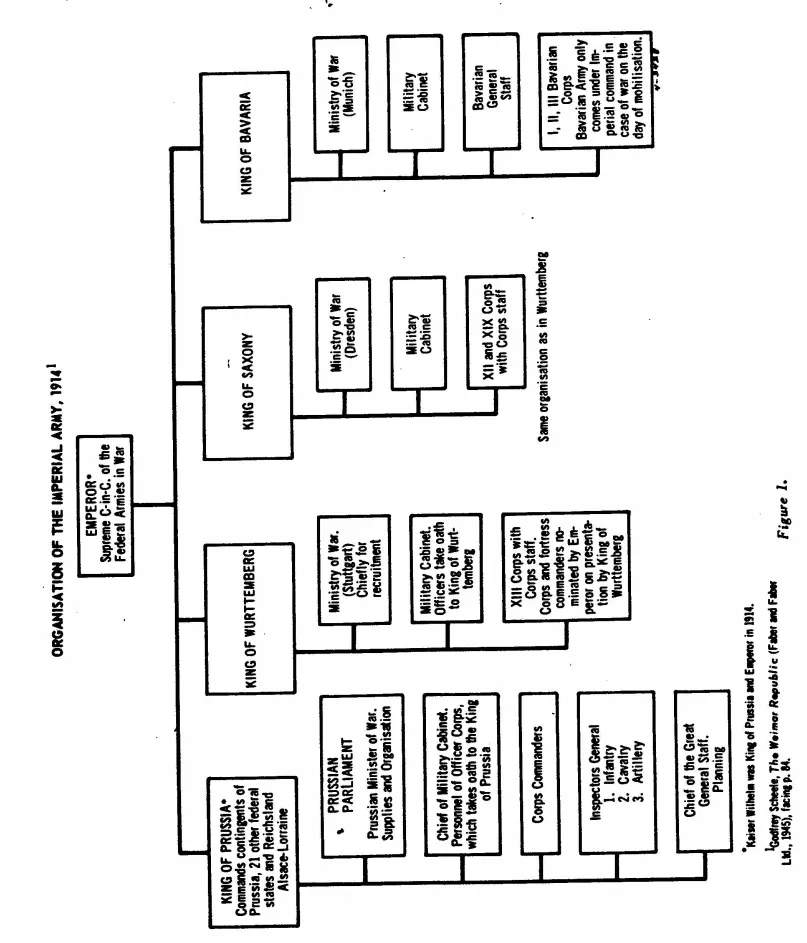

Figure 1.

![]()

When the Field Marshal and General Groener arrived at the Emperor’s palace on 9 November Field Marshal von Hindenburg was incapable of telling the Emperor that the Army was no longer loyal to him. Prussian military tradition labeled such action as disloyal. “Hindenburg made an effort to speak, but his voice choked and he could not. With tears running down his face he begged his Emperor’s leave to resign.”{6} Then Field Marshal von Hindenburg ordered General Groener to explain the situation to Kaiser Wilhelm. This General Groener did, stating quite plainly that an operation against the interior would mean civil war and that there could not be, under the circumstances, any guarantee that the armed forces could be controlled. The Emperor exclaimed that he would lead his army against the rebels. General Groener answered that the Army no longer stood behind the Emperor. “Have they not taken the military oath to me?” “In circumstances like these, Sire, oaths are but words,” answered General Groener. {7} In the words of one author, “With these words, the whole world of Prussia and particularly the world of the Prussian Army was shattered….”{8}

On the evening of 9 November, General Groener read the terms for the armistice. He telephoned a friend, Chancellor Friedrich Ebert, the leading Social Democrat who was elected by the Reichstag to head a new government. {9} General Groener informed Chancellor Ebert that the High Command would support the new government in exchange for assurance that the government would support the Officers’ Corps and properly maintain the Army. In addition, General Groener indicated that the Officers’ Corps expected the government to fight against Bolshevism and that the Army was available to help the government for this purpose. Chancellor Ebert concluded the conversation with words of thanks for the support of the Army.

When the armistice was reached on 11 November 1918, there were four political forces active in Germany: the High Command; the dissolving armies of defeated Germany; the official government of Chancellor Ebert; and the revolutionaries. {10}

General Groener had, to some extent, anticipated the loss of control that accompanied the end of the war. He and his staff had drawn up a three-point plan for the High Command—the troops along the Western Front would be withdrawn behind the Rhine; order would be restored and military discipline enforced; and strong forces would be sent to the Eastern Front to hold the Ukraine, Poland, and Baltic areas to establish a barrier against Bolshevism. {11} But to save the German position in the East, and to avoid a civil war, General Groener realized that Germany’s internal conditions would have to be stabilized as quickly as possible.

Chancellor Ebert and the Social Democrats were not prepared for the power that was thrust upon them on 9 November. {12} One thing seemed reasonably certain: “Whoever controlled the field army might be able to control the course of the revolution.”{13} The Field Army was itself divided into two parts: the High Command which included the General Staff, and the returning troops. Chancellor Ebert was forced to make a choice. He could either choose the High Command and the forces it still controlled, or he could organize the Soldiers’ and Workers’ Councils. {14}

In making his decision, Chancellor Ebert faced another consideration. The withdrawal of the troops from the Western Front would be a complex maneuver, and only the General Staff was capable of executing it within the time limit established. If the withdrawal got out of control, Germany faced the possibility of civil war. Chancellor Ebert had little choice but to side with the High Command.

Field Marshal von Hindenburg’s consent to the agreement reached by General Groener and Chancellor Ebert opened up the way for General Groener to implement his program to save what could be saved of the German Army, a plan that called for the predominance of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL), the Army High Command, over all other centers of military power. The agreement with Chancellor Ebert left the OHL free to move against the radical revolutionaries and to demobilize the dissolving masses of soldiers.

To accomplish his objective, General Groener used a tactic perfected by General Erich Ludendorff—the “doctrine of responsibility.”{15}This doctrine implied that the High Command could only stand behind those actions of the government which it approved. If any action of which it did not approve was carried out, then the High Command would resign and refuse to support the government.

General Ludendorff had used this principle to establish his authority over the Emperor and the cabinet during World War I. When Chancellor Ebert agreed to use the OHL to suppress the revolution, he passively accepted this doctrine.

The High Command then proceeded to resolve the problems of the revolution. On 10 November, delegates of the Soldier’s Councils were persuaded to support the High Command, a victory easily won because only the General Staff had the technical competence to carry out the troop withdrawals ordered by the Allies. {16}

General Groener realized that the real test would come in Berlin when the withdrawing troops arrived from the front. His plan called for nine trustworthy divisions under General Freiherr von Lequis, who was to be Military Commandant of Berlin, to enter the city on 5 December and disarm the civilian population. {17}

Chancellor Ebert could not make up his mind, while the Independent members of the cabinet definitely opposed organized troops entering Berlin because of fear of widespread bloodshed. On 6 December, Chancellor Ebert was forced to make a decision. On that day, Count Wolff Metternich led an abortive putsch (riot) against the government, and Chancellor Ebert called General Groener for help. He was informed that if aid were given, the High Command would expect the government to allow General von Lequis to enter Berlin; otherwise, the High Command would withdraw its support from the government. This was General Groener’s first application of the doctrine of responsibility.{18}

Chancellor Ebert acquiesced; on 12 December, the Guards Cavalry Rifle Division—some 800 strong—entered Berlin.

The day before, on 11 December, the first troops had returned to Berlin from the front. Chancellor Ebert and the Socialists had made elaborate preparations to receive them. Chancellor Ebert—addressing them in front of the Brandenburger Gate: “I salute you, who return unvanquished from the field of battle”—naively intended to win the support of the disbanding soldiers. {19} In this he failed.

The average attitude of the soldiers from the front was expressed by one who said:

“The “reception committee” under Ebert’s leadership and his speech had no effect on us. We were only aware of one fact: That the fight against the “masses of mankind” would be hard and bloody … it would now be necessary to fight all physical and psychological resistance, to become hard—even against ourselves —to become free of all sentimentality. A great task lay before us.”{20}

The returning soldiers became the decisive element in Berlin, and the General Staff lost control of the situation. The demobilization plan broke down completely. Chaos reigned. Each political faction attempted to win the support of the mobs of soldiers.

The People’s Deputies issued a decree on 12 December which called for the formation of a Republican Civil Guard, an attempt to dispose of the High Command. The Congress of Soldiers’ Councils met on 16 December, and, on the following day, asked that Field Marshal von Hindenburg and the General Staff be dismissed, and the Hamburg program adopted.{21} The latter called for the abolition of all badges of rank and the formation of a Republican Civil Guard. The Army High Command was infuriated.

Hopeful of some reconciliation, Chancellor Ebert called a meeting of the OHL, the People’s...