![]()

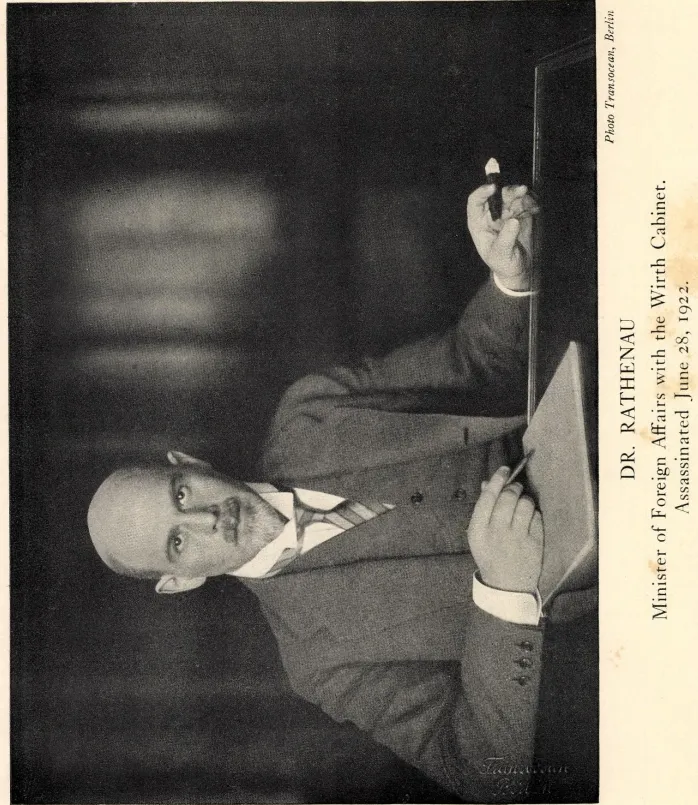

CHAPTER I — GERMANY AND THE LEAGUE—ASSASSINATION OF RATHENAU

Prolongation of my Mission—A talk with the Prime Minister—Germany and the League—Rathenau and Stinnes at the American Embassy—Rathenau assassinated—The reaction in Berlin—An American Observer on the League—A Czecho-Slovak view—Wirth’s courage—The Chancellor on the League—German finance—Weariness of Control Commission

London, June 12, 1922.—I asked the Prime Minister this morning how long he wanted me to stay in Berlin, as the two years for which I originally signed on are nearly up. He said: “You must not think of leaving until the present business is settled. This is only the first act. The conclusion will not come this year. You must stay until the present financial phase is completed. I hope that you will do so and that you do not find life in Berlin too difficult.”

REGARDING the League of Nations, Lloyd George was decidedly of opinion that Germany ought to be brought in. It was essential that the world should learn to treat Germany again as an equal; both she and Russia had been treated as below the salt. Even if Germany received at Genoa one or two snubs, and some humiliation, it was expedient that she should rejoin the comity of nations and that all should belong to the League. Lloyd George had formed a very favourable opinion of Wirth and of his honesty. What Wirth stated were facts, or, if they were not facts, he believed them to be so, and that was the essential. Rathenau had been a great bore. After allowing Wirth to speak for two or three minutes, he broke in with, “Now, Mr. Lloyd George, I want to explain to you the terrible position of the mark,” and he went on lecturing for forty minutes or more, so that nobody could ask a question or get an answer.

LONDON, June 14, 1922.—A leading English politician is alleged to have said: “Were I a German, I would neither pay nor carry out the Treaty. The French have irritated and bullied Germany beyond all bearing, and I would say: ‘Very good; occupy the Ruhr and do any damned thing you like. Meantime, Germany shall send all her engineering force and military equipment force to Russia, and in five years we shall summon France to give the Ruhr back again.’”

VERY dashing—but not wise or practical. England must endeavour to prevent either side proceeding to extreme measures.

LONDON, June 21, 1922.—The question of Germany’s entry into the League of Nations is becoming urgent, and is being much discussed here in Government circles. One view is that England can take no action without asking France first as to her willingness to admit Germany. The solitary but sufficient objection to this course is that Poincaré is certain to decline. If the question is put to Paris, there can be no doubt about the answer. It may be better to let the decision come on at Geneva. The strong view in London is in favour of Germany’s admission to the League, and there is no objection to this being stated in Berlin. Government circles here believe that the German admission will be voted either unanimously or by a large majority.

THERE remains the question of Germany’s nomination to a seat on the Council. England will certainly afford support to this nomination.

BERLIN, June 28, 1922.—Rathenau assassinated.

Mr. ALANSON B. HOUGHTON, U.S. Ambassador at Berlin from February, 1922, to February, 1925, has given me the following account of the dramatic meeting between Rathenau and Stinnes at the American Embassy on June 27, 1922—the night before Rathenau was shot.

The meeting between Rathenau and Stinnes came about as follows: A day or two before, Logan (assistant to Mr. Boyden, Unofficial Observer of the United States to the Reparations Commission) wired that he was coming to Berlin to discuss certain matters relative to coal deliveries. I sent word to this effect to Rathenau, and suggested that it might be useful if he came to dinner and had a talk with Logan, to which he replied that he would be glad to come. Dinner was set for eight o’clock. It was fully 8.30 when Rathenau arrived. He was in a state of high excitement. Helfferich, he explained, had just made what he termed a “slashing attack” on him personally in the Reichstag and he was evidently apprehensive about its possible effect. We then went in to dinner. After a little general conversation the matter of coal deliveries was taken up and discussed at some length, until finally Rathenau turned to me and asked if I would object to his inviting Stinnes to join us. Stinnes, he said, was much more familiar with the coal situation than he, and could furnish all the necessary facts. That was obviously true, but I knew, of course, that the relations between Rathenau and Stinnes had been strained, and it occurred to me that possibly what Rathenau really wanted was to take advantage of this opportunity to bring about a meeting with Stinnes for other and more personal reasons. Inasmuch as I could see no reason why such a discussion should not take place under my roof and the interview bade fair to be distinctly interesting, I promptly assented. Directly Stinnes could be located, therefore, Rathenau telephoned him, and Stinnes sent word back in reply that as soon as he had finished his own dinner he would come to the Embassy. He arrived about 10.30 and a lively discussion regarding the coal deliveries at once ensued. This went on for perhaps an hour, when Stinnes turned abruptly from the subject in hand and began a sharp attack on Rathenau. He said that he was confident Rathenau had made a serious blunder in entering the Government at all and that he should lose no time in leaving it. Rathenau replied, with a laugh, that someone obviously had to do the necessary work and that he felt by joining the Government he was contributing what he could do to the best interests of Germany. Thereafter, for a couple of hours, the two discussed with great frankness and considerable warmth their differences regarding politics, both at home and abroad. When they left the Embassy, somewhere between half-past one and two o’clock on the morning of the 28th June, the debate was still being vigorously pressed, and, as Stinnes told me afterwards, they went to the Hotel Esplanade, where Stinnes was living, and continued their talk until nearly four o’clock, when Rathenau finally went home. The definite impression left on my mind was that the two men, for reasons of their own, were each seeking some sort of agreement. In fact, talking over with me the events of the evening a few weeks later, Stinnes told me he felt that in essentials they had come together, and that a working programme was possible. The decisive part of the talk evidently developed after they left the Embassy.

WHEN I entered my office the following morning, June 28th, I was shocked beyond measure to learn that Rathenau had been murdered a few moments before, while motoring from his home to the Foreign Office.

Berlin, June 29, 1922 (the day after the assassination of Rathenau).—Arrived in Berlin last night, punctually to the minute. Not much disorder or confusion on the railways, but indications of suppressed political excitement in the towns we came through. Here in Berlin there is a general strike of twenty-four hours, but that is quite a normal occurrence. This one is designed to be a demonstration and warning to the Right that the working classes will not stand anything like a monarchical putsch. The general feeling appears to be one of profound horror at the Rathenau assassination. Even in anti-Semitic circles indignation is expressed, if not felt. The demonstrations of the working classes in all the big towns have been imposing, although the extreme respectability of appearance and soberness of demeanour of the German workmen rob these manifestations of the dramatic and picturesque which would characterize more primitive participants.

ANY chance of a successful monarchical putsch which may have existed before the murder is now thought in government circles to have vanished. Stresemann, the Volkspartei leader, who is considered a strong monarchist and indeed admits it, has had to make vehement declarations dissociating himself and his friends from the Extreme section of the Nationalists. The latter group, though isolated and temporarily cowed, remain, however, as malevolent and bloodthirsty as ever. One of them, a relation of the murderers of Erzberger, is reported to have said, “My little brother Karl has killed the first pig, but there are more to follow.”

WIRTH has behaved with courage and good sense. He is quite undismayed by the personal danger he is constantly in. His first movement was to hold the Entente, notably France, responsible for Rathenau’s death. He is reported to have said: “If the policy of fulfilment and the Government which supported it had only received more encouragement from the Entente, hostile sections in Germany would not have dared to push their opposition to so violent an extent. Poincaré is a conscious or unconscious confederate of Helfferich, and Helfferich’s speeches, by their bitterness and vehemence, have stimulated assassination.”

NEITHER accusation is just. Helfferich’s speech the other day—which is alleged to have brought about the assassination—was not of an exceptionally violent character: indeed, as such speeches go, it does not appear to me to be open to much criticism. On some points he even praised Rathenau, although he criticized bitterly the general policy of fulfilment and its failure to elicit benefits in exchange.

WHETHER Wirth’s insinuation that unrewarded and unrecognized fulfilment by Germany brought about the assassination is true or not, it has not diminished the number of those who consider fulfilment, within the limits of the possible, to be the only wise course for Germany. The advocates of this policy are at least as strong as before—perhaps stronger.

BERLIN, June 30, 1922.—A long interview with an American observer in which the present situation was frankly discussed.

HE WAS distinctly pessimistic regarding the outlook in Germany; said that he was already tired of the work here. The situation was difficult, if not hopeless: there was no possibility of any co-operation with the Diplomatic Corps, by which I suppose he means with the French and the Italians. He further said: “Americans here must work along with you and do what they can from the American standpoint, which is essentially that of an unofficial observer, but we can’t get on with those other fellows. The German Government gives me what information we want and we shall just make use of that and keep our people advised. As to the loan question, everybody in Germany is hostile to the idea of a small loan. All the big industrials, Stinnes, Thyssen, and others, tell us: ‘We will not allow a loan of any kind until the whole question of reparations and sanctions has been settled. There is no good whittling at this or that detail. We must have the whole matter put right. There can be no guarantee for the service of a loan as long as the menace of sanctions remains.’”

I POINTED out that if this attitude meant that the whole of the safeguards provided in the Treaty of Versailles would have to be revised it appeared an impossible proposition to put before the French Government. It would be wiser to get the loan under way because the moment a loan, even a comparatively small one, was within reach, the more aggressive French politicians would lose a good deal of bourgeois and banking support. France had such an urgent need of funds that she might modify her attitude if money was in sight.

REFERRING to the League of Nations, my friend said: “We Americans think the German Government are very unwilling to come into the League. They would not gain by it. You can say, ‘They would be on an equality with other nations’—that is not worth much. As to America’s entry, if you ask what the probability of that is, any damned fool can see that there is not the faintest chance of America ever modifying her attitude regarding the League of Nations. American hostility to any political participation in Europe is just as fundamental as England’s view about Sea Power. There may be no reason for either—it is just instinct. But if Europe wants assistance on the economic basis you will find America respond. You can have everything you want economically—nothing politically.”

THE new Stresemann Government, if only because of the inclusion within its ranks of the Socialists, had been distasteful from the first to the Bavarian Chauvinists. It required but the definite abandonment by the courageous Chancellor of the policy of passive resistance in the Ruhr to produce a violent reaction in Munich. Eventually this took the form of a public repudiation by Bavaria of the Versailles Treaty, of a proclamation of a “State of Exception” and of the appointment as State Commissioner with dictatorial powers of Herr von Kahr, a noted monarchist who was also honorary President of the leading Bavarian reactionary associations. Dr. Stresemann, dissatisfied with the assurance received from Munich that the above measures of exception were exclusively directed against the new Nationalist organization headed by Herr Hitler{2} and General von Ludendorff, replied by himself proclaiming a state of siege throughout the Reich and investing the Reichswehr Minister with full powers. These Dr. Gessler in his turn delegated to the Reichswehr Commander, General von Seeckt, and to the commanders of the seven military districts. Of these commanders, the one in charge of the Bavarian military district, General von Lossow, was himself a Bavarian and had previously had some personal unpleasantness with General von Seeckt. Lossow was not long in disobeying the orders issued by General von Seeckt, and was supported in his open insubordination by the Bavarian Government. Thereupon, he was summarily dismissed by the Reichswehr Minister, but, instead of relinquishing his command, he allowed himself to be reappointed Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr in Bavaria by the Munich Government. A grave clash between Bavaria and the Central Government now appeared unavoidable. A further injunction addressed to Munich by the Chancellor demanding the immediate restoration of the constitutional authority of the Reichswehr Ministry over the Reichswehr in Bavaria met with a flat refusal from Herr von Kahr. This was civil war.

ON THE evening of November 8, 1923, Herr von Kahr was about to deliver a much-advertised address on Marx...