- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bridges and Men

About this book

Since human time first began, men have needed to cross streams and valleys, span chasms and torrents—and have found ways of getting to the other side. In this sweeping historic survey, Joseph Gies, author of Adventure Underground: The Story of the World's Great Tunnels, recounts for our pleasure the history of bridges through the ages.

From the first vines thrown across small streams to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge across the entrance to New York Harbor and to plans for possible bridges across the English Channel and the Straits of Messina, Mr. Gies interests us in the men who dreamed bridges and built them; in the terrible catastrophes of bridges that collapsed—including that across the First of Tay and "Galloping Gertie" across the Tacoma Narrows; in painters and poets and novelists who have found their inspiration in or on bridges.

In large part, that is, BRIDGES AND MEN is about practical visionaries who combined the genius of engineers and architects, the talents of propagandists and business men: The Bridge Brothers, who built the world-faced Pont d'Avignon; Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, who built the Pont de la Concorde; john Rennie, the Scottish farmer boy who built New London Bridge; George and Robert Stephenson, who invented the railroad and railroad bridge; and Thomas Telford, who bridged the ocean at Menai Strait.

From the first vines thrown across small streams to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge across the entrance to New York Harbor and to plans for possible bridges across the English Channel and the Straits of Messina, Mr. Gies interests us in the men who dreamed bridges and built them; in the terrible catastrophes of bridges that collapsed—including that across the First of Tay and "Galloping Gertie" across the Tacoma Narrows; in painters and poets and novelists who have found their inspiration in or on bridges.

In large part, that is, BRIDGES AND MEN is about practical visionaries who combined the genius of engineers and architects, the talents of propagandists and business men: The Bridge Brothers, who built the world-faced Pont d'Avignon; Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, who built the Pont de la Concorde; john Rennie, the Scottish farmer boy who built New London Bridge; George and Robert Stephenson, who invented the railroad and railroad bridge; and Thomas Telford, who bridged the ocean at Menai Strait.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.—How Bridges Were Invented

THE history of anything—bathing suits, furniture, baseball, cooking—is a part of the history of everything, but some of the threads are more fundamental to the whole tapestry than others. Few of man’s inventions are more basic than the bridge. The oldest engineering work devised by man, it is the only one universally employed by him in his precivilized state. In the Dartmoor district of England you may still see streams or dry stream beds into which huge monolithic slabs of granite were dragged to serve as the vertical piers and horizontal beams of millennia-old crossings. In other places, timber piles have survived the ages to reveal the engineering capacities of our remote ancestors.

What is incredible is that our distant forebears in many parts of the globe, struggling to overcome the transportation problems of their primitive trail-worlds, invented not only the simple beam bridge but also the far more sophisticated, even ultramodern forms of suspension and cantilever. In the interior of South America men first learned to swing across a chasm on a vine, like monkeys. Then the vine’s end was fastened to the farther side to be available for the return journey. Next it was made secure and crossed repeatedly by hand-over-hand acrobatics. Several vines fastened together were stronger: two or three such cables fixed parallel to each other made the crossing less hazardous. Eventually the idea developed of laying a floor of transverse branches, which later became more solid. Prescott gives this description of spans found by the Spaniards in the Inca Empire:

Over some of the boldest streams it was necessary to construct suspension bridges, as they are termed [Prescott is writing in 1847], made of the tough fibres of the maguey, or of the osier of the country, which has an extraordinary degree of tenacity and strength. These osiers were woven into cables of the thickness of a man’s body. The huge ropes, then stretched across the water, were conducted through rings or holes cut in immense buttresses of stone raised on the opposite banks of the river, and there secured to heavy pieces of timber. Several of these enormous cables, bound together, formed a bridge, which, covered with planks, well secured and defended by a railing of the same osier materials on the sides, afforded a safe passage for the traveller. The length of this aerial bridge, sometimes exceeding two hundred feet, caused it, confined as it was only at the extremities, to dip with an alarming inclination towards the centre, while the motion given to it by the passenger occasioned an oscillation still more frightful, as his eye wandered over the dark abyss of waters that foamed and tumbled many a fathom beneath.

Yet these light and fragile fabrics were crossed without fear by the Peruvians, and are still retained by the Spaniards....

Despite the precariousness, these Peruvian suspension spans were used not only for pedestrian traffic but also for burden-bearing llamas.

In north-east India, suspension bridges consisting of single bamboo cables were stretched across streams. The bamboo was taut, like a tightrope. The traveler wishing to cross performed what amounted to a circus feat. Armed with a loop of bamboo, he climbed the tree to which the cable was fastened, fitted his loop on the tightrope, and dropped his weight onto it, causing the cable to sag. With increasing velocity, he shot out over the torrent, as the cable sagged deeper and deeper; his momentum even carried him partway up the other side. Then, grasping the cable with his hands and holding the loop with his legs, he pulled himself the rest of the distance into the tree that served as the tower on the far bank.

Such “transporter” bridges were still common in Tibet and north-east India in the nineteenth century. Usually by this time the passenger simply rode in the loop, which was hauled across by a light cable. On the opposite side of the world, in the Shetland Islands north of Scotland, one of the outlying crags was connected to a bigger island by the same kind of bridge as late as a hundred years ago. In South America a basket was hung on the main cable, and the passenger, seated in the basket, pulled himself across by hauling on a movable cable.

But in Assam and Burma, as in Peru, real suspension bridges, with floors and handrails, evolved from these beginnings. Some were hundreds of feet long, stiffened at intervals to keep the floor from closing in on the traveler. On the west coast of Africa, too, suspension bridges were made of tough roots plaited together and hung from trees on either side of a stream.

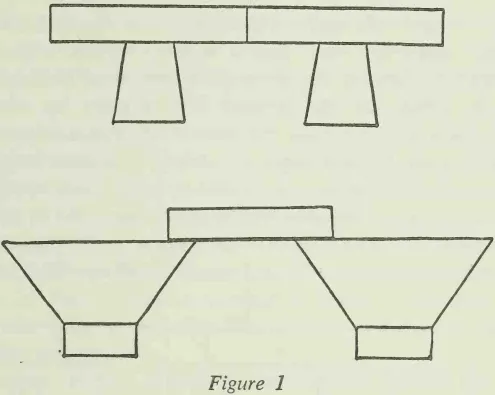

Nobody knows when the first cantilever bridge was built, but it was in the very distant past, in China. A cantilever is a balanced structure extending laterally in two directions, from a base or pier—like a V on a pedestal, or a cocktail glass—which can be raised on each side of a river either to meet in the middle or to support a suspended span (Figure 1).

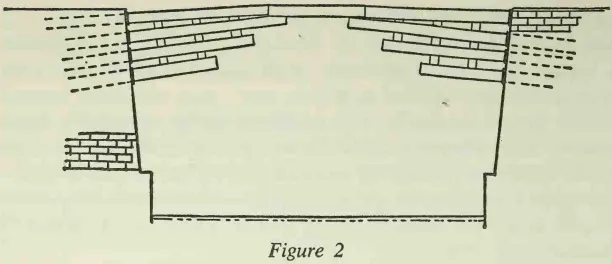

In China cantilevers were built by extending heavy timbers outward from a solid stone abutment. The stones were fitted together without mortar. The timbers were roughly hewn treetrunks, projected in pairs, placed with an upward slant, usually in three or four pairs, with the inner ends held by the weight of the stone abutment, the outer ends bound together (Figure 2).

For early man, with his limited access to materials and his limited means of refining them, these bridge forms, ingenious as they were, had only very restricted value. They served for narrow crossings under favorable circumstances. Civilization demanded something better. Above all, the invention of the wheel, with its dramatic train of carts, wagons, roads, highways, merchants, wealth, towns, and cities, brought the problem of river crossings to the fore.

The invention that solved the bridge problem of ancient civilization ranks second only to the wheel itself. It is the arch. How this marvel came into being is as deep a mystery as the origin of the wheel. Engineers discount the older guess that man built arches in imitation of nature, for the natural arch formed by erosion is structurally quite different from the stone arch. Another guess, that bridging of streams by dumping rocks led to a sudden insight also is farfetched. Archaeologists have found that the arch appeared in tombs and underground temples long before it was used as a bridge. Recent excavations have disclosed underground vaults going back to the fourth millennium B.C. at Ur and elsewhere in ancient Sumer, the earliest Tigris-Euphrates civilization. Egyptians, too, knew vaulting by the year 3000 B.C.

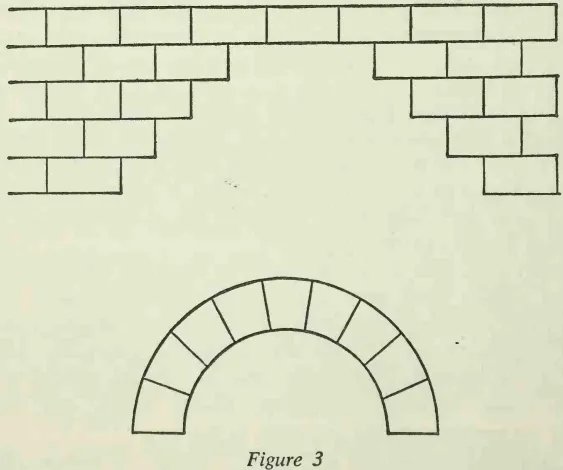

The Sumerians and Babylonians apparently had the “false arch” at a very early date, and perhaps derived the true arch from it. The difference between the two is interesting. The false arch, built of overlapping bricks laid horizontally and held together by mortar, will stand, but it will not carry a load. A true arch, on the other hand, will sustain an enormous weight, even without any mortar (Figure 3).

Who built the first arch bridge? Diodorus of Sicily describes a bridge across the Euphrates built by “Queen Semiramis of Babylon” about 2000 B.C. But even if we overlook the legendary character of this queen, Diodorus’ description indicates that the bridge consisted not of arch spans but of simple beams on piers twelve feet apart. This construction was quite possible over the Euphrates, which was reduced to a trickle in the dry season. Herodotus ascribes a bridge over the Euphrates to another queen, Nitocris, and gives it stone piers with wooden flooring. A modern writer places the bridge in Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (sixth century B.C.). If so, then it was not the first stone arch, even assuming it was an arch. The oldest surviving stone arch is at Smyrna, in Turkey, over the Meles River. It dates at least from the ninth century B.C., and is said to have been crossed by St. Paul. Several stone-arch bridges in Israel antedate the Christian era (even though the Old Testament does not contain a single bridge reference).

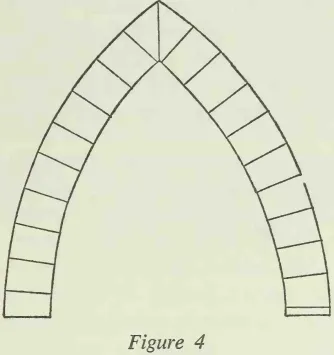

Stone arches are not necessarily semi-circular, though this is the form we usually think of (and by far the commonest in bridging). Early stone arches of the eastern Mediterranean were pointed (Figure 4). Pointed brick arches in drainage tunnels have been found in the supposed palace of Nimrod on the Tigris, dating from 1300 B.C. A mud-brick pointed arch at Nippur goes back to the fourth millennium B.C. Semi-circular “voussoir” arches—that is, true arches made with wedge-shaped stones—have been found at the ruins of Khorsabad near Ninevah, dating from about the reign of Sargon II of Assyria (722–705 B.C.).

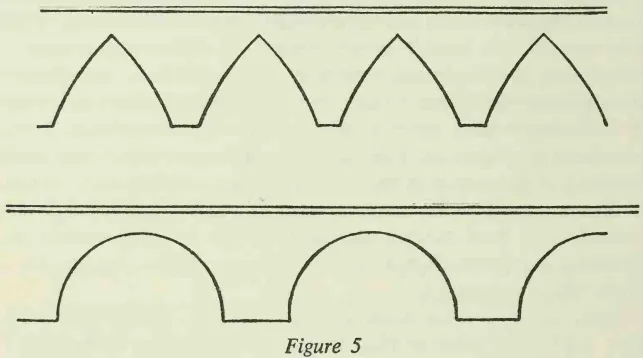

The semi-circular arch has an obvious advantage over the pointed arch when it comes to bridging—fewer piers are needed in the river. The pointed arch has an advantage too, but bridge builders did not discover it for a long time (Figure 5).

Hundreds and hundreds of years passed before kings and pharaohs and their officials and officers discovered the great application of the priceless engineering tool in their hands. Restricted to what amounted to a decorative role in tombs, temples, and palaces, the arch existed for at least two thousand years before it was ever used as a bridge.

For its serious application, the stone arch, like many other Greek, Persian, and Egyptian inventions, awaited the coming of the pragmatic, inartistic, strangely gifted Romans.

2.—The Mighty Roman Arch

THE Tarquins, Etruscan kings of Rome in its remote pre-Republican stage, brought Etruscan experts to their Tiber principality in the seventh century B.C. to solve a civil-engineering problem that has persisted into modern times: sewage disposal. Their vaulted tunnel, the Cloaca Maxi...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- FOREWORD

- 1.-How Bridges Were Invented

- 2.-The Mighty Roman Arch

- 3.-The Engineer Vanishes from Europe but Appears in Asia

- 4.-The Bridge Brothers Build the Pont d’Avignon

- 5.-Weird and Wonderful, Appalling and Amazing Old London Bridge

- 6.-Out of the Middle Ages by the Rialto Bridge

- 7.-Heart of Paris: The Pont-Neuf

- 8.-The “Flying Arch”: Jean-Rodolphe Perronet

- 9.-A Scotch Farmer Boy Builds London Bridges

- 10.-Thomas Telford Spans the Menai Strait

- 11.-The Yankee Bridge

- 12.-The Stephensons Invent the Railroad and the Railroad Bridge

- 13.-The Age of Disaster

- 14.-The Mystery of the Firth of Tay

- 15.-James Eads Falls in Love with the Mississippi

- 16.-Captain Eads Builds a Triple Steel Arch

- 17-John Roebling Spans the Niagara Gorge

- 18-The Brooklyn Bridge: Grandeur and Tragedy

- 19.-The Monster in the Firth of Forth

- 20.-Quebec: A Cantilever Crashes

- 21.-The Automobile Age: Beauty and Trouble

- 22.-Who Wrecked Galloping Gertie?

- 23.-After Gertie, What?

- 24.-“By the Rude Bridge that Arched the Flood”

- 25.-Bridge Firsts, Bridge Cities, Bridge Sports

- 26.-The Endless Bridge

- APPENDIX

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bridges and Men by Joseph Gies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.