- 103 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

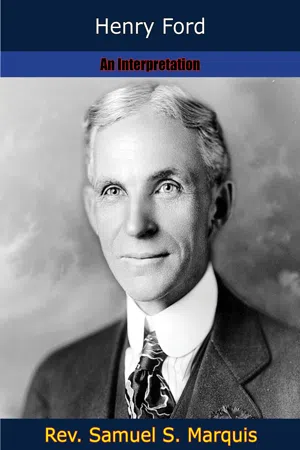

First published in 1923, this biography is widely regarded by many automotive historians as the finest and most dispassionate character study of Henry Ford ever written. Written by the Reverend Samuel S. Marquis, an Episcopalian minister who was also the head of the sociology department at Ford Motor Company, this collection of essays serves to analyze the "psychological puzzle such as the unusual mind and personality of Henry Ford presents."

A gripping read for history buffs and fans of historical biographies.

"Students of Henry Ford should be delighted by this republication of Samuel S. Marquis's shrewd evaluation of the legendary industrialist. A close friend and associate of Ford for many years, Marquis developed many compelling insights into the automobile maker's character and personality. One comes away from this book with a much greater sense of what made Ford tick."—STEVEN WATTS, Professor of History at the University of Missouri-Columbia and author of The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century

"Marquis was the first Ford intimate to criticize the industrialist in print. Aware that he was treading on thin ice, Marquis recalled that Ford had told him that 'the best friend one has is the man who tells him the truth.' Hopefully, the clergyman remarked, '[he] will receive the critical portion of these pages in the same spirit.' Ford emphatically did not...Marquis's book would have been widely read had not the Ford organization been fairly successful in buying up copies and persuading book dealers not to sell it."—DAVID L. LEWIS

A gripping read for history buffs and fans of historical biographies.

"Students of Henry Ford should be delighted by this republication of Samuel S. Marquis's shrewd evaluation of the legendary industrialist. A close friend and associate of Ford for many years, Marquis developed many compelling insights into the automobile maker's character and personality. One comes away from this book with a much greater sense of what made Ford tick."—STEVEN WATTS, Professor of History at the University of Missouri-Columbia and author of The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century

"Marquis was the first Ford intimate to criticize the industrialist in print. Aware that he was treading on thin ice, Marquis recalled that Ford had told him that 'the best friend one has is the man who tells him the truth.' Hopefully, the clergyman remarked, '[he] will receive the critical portion of these pages in the same spirit.' Ford emphatically did not...Marquis's book would have been widely read had not the Ford organization been fairly successful in buying up copies and persuading book dealers not to sell it."—DAVID L. LEWIS

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I—THE FORD HALO

I HAVE known Henry Ford for twenty years. For a time he was my parishioner, and then for a time I was his employee.

Given freedom to create a man will reveal himself in what he produces—the painter in his picture, the sculptor in his marble, the writer in his book, the musician in his composition, and the mechanic in his machine. The Ford car is Henry Ford done in steel, and other things. Not a thing of art and beauty, but of utility and strength—the super-strength, power and endurance in engine and chassis, but somewhat ephemeral in its upper works. With top torn, body dented, upholstery gone, fenders rattling, and curtains flapping in the wind, you admire the old thing and speak softly and affectionately of it, because under the little hood the engine—occasionally on four, sometimes on three, frequently on two, and now and then on one—keeps rhythmically chugging along, keeps going when by all the laws of internal combustible things it ought to stop and with one weary expiring gasp fall to pieces and mingle with the mire its few remaining grains of rust. But it keeps going, just as he keeps going contrary to all the laws of labor, commerce and high finance.

Some years ago I sat in the office of a Ford executive, discussing with him a certain thing the “chief” had ordered done. “It’s a fool thing, an impossible thing,” said the executive, “but he has accomplished so many impossible things that I have learned to defer judgment and wait the outcome. Take the Ford engine, for example; according to all the laws of mechanics the damned thing ought not to run, but it does.”

As in the Ford engine, so in Henry Ford there are things that by all the laws of ordinary and industrial life should “queer” him, put him out of the running, but he keeps going.

He is an extraordinary man, a personality in the sense that he is different from other people, quite different, for that matter, from what he is popularly supposed to be.

But however unlike the rest of us Henry Ford may be in some respects, he falls under the classification of ordinary mortals in this: he is not satisfied with what he has and is.

He is one of the richest men on earth. He is the most widely known man in the industrial world. But with these things he is not content. He has other ambitions. For example, he not only has the willingness, but has shown a rather strong desire to assume national political responsibilities. And on one occasion he voluntarily took upon himself the task of settling the problems of a world at war. His ability to do in other than the industrial sphere may be commensurate with his will, but his efforts in other directions have not been such as to inspire confidence.

It is not only the absence of certain qualifications, but the presence of others that make us doubt his fitness for the field of politics. If our Government were an absolute monarchy, a one-man affair, Henry Ford would be the logical man for the throne. As President, and he seems to have aspirations in that direction, he would be able to give us a very economical administration, for a Cabinet and Congress would be entirely superfluous if he were in the White House. The chances are that he would run the Government, or try to do so, as he runs his industry, having had experience along no other lines. The Ford organization would be transferred to Washington. That would not be so difficult a matter as it might appear to the uninitiated. It could be accomplished in a single section of a Pullman car, with one in the upper and two in the lower berth. I agree with Mr. Edison, who was recently reported as saying of Mr. Ford, “He is a remarkable man in one sense, and in another he is not. I would not vote for him for President, but as a director of manufacturing or industrial enterprises I’d vote for him—twice.”

But I doubt if the spark of political ambition in him ever would have burst into flame had it been left to itself. There are those near him, however, who never cease to blow upon it and fan it, being themselves ambitious to sit in the light of the political fire which by chance may be kindled in this way. They seem to entertain no doubt of their ability to run any office for him from that of the Presidency down.

But Henry Ford has left upon me the impression that his chief ambition is to be known as a thinker of an original kind. He has the not uncommon conviction among mortals that he has a real message for the world, a real service to render mankind.

“I want to live a life,” he said to me some years ago when we were returning from Europe after the Peace Ship fiasco. “Money means nothing to me—neither the making of it nor the use of it, so far as I am personally concerned. I am in a peculiar position. No one can give me anything. There is nothing I want that I cannot have. But I do not want the things money can buy. I want to live a life, to make the world a little better for having lived in it. The trouble with people is that they do not think. I want to do things and say things that will make them think.”

In my opinion he could realize his supreme ambition if he were to follow the example of a good shoemaker and stick to his last, that is, to the human and production problems in industry, and leave national, international and racial problems alone. It is human to grow weary of achievement in one direction. Like Alexander, we tearfully long for adventures in other worlds instead of trying to bring a little nearer to perfection the world we have conquered.

For many years Mr. Ford shunned the public gaze, refused to see reporters, modestly begged to be kept out of print; and then suddenly faced about, hired a publicity agent, jumped into the front page of every newspaper in the country, bought and paid for space in which he advertised what were supposed to be his own ideas (although he admitted in the Chicago Tribune trial that he had not even read much that had been put out under his own name) and later bought a weekly publication and began to run “his own page.” I think he would rather be the maker of public opinion than the manufacturer of a million automobiles a year, which only goes to show that in spite of the fact that he sticks out his tongue at history, he would nevertheless not object to making a little of it himself.

This laudable ambition to serve the world, and, in some degree, to mold its thought, has very naturally aroused in men the desire to know more intimately this man who volunteers to take the part of Moses—he doesn’t put it just this way—in a world-exodus into a new era of peace and prosperity. Having made himself a world figure, or persisting in being reckoned as one, the world insists, and properly so, on knowing all there is to know about him. It is the price every man must pay for aspiring to such an exalted position.

“Tell me now, in confidence, is Henry Ford as great a man as the people generally believe him to be? Is he the brains of the organization which bears his name? Is its success due to him, or to the men he has gathered about him? Is he anything more than a mechanical genius? Is it true that he cannot read and write? Is he a financier? Does he keep in touch with the details of his business? Is he a hard worker? Is he sincere, or a self-advertiser?” These are some of the questions people keep asking you if you chance to have a fairly intimate acquaintance with Henry Ford.

The “tell me now in confidence” phrase is significant. It means that the questioner has a lurking suspicion that the popular idol of Dearborn is not all gold. There must be some clay in his make-up. It would be a great satisfaction to have a well authenticated sample of the clay.

Not long ago I delivered an address on the Ford way of handling labor. The membership of the organization to which I was speaking was composed chiefly of working men. The president of the club introduced me and closed his remarks by saying, “Now that you are no longer in the employ of Henry Ford, tell us the truth about him.” The same lurking suspicion. If only the truth were told! If only those who know him intimately would tell all they knew,—well, if it did not take the halo from his head it might, at least, give it a jocular slant.

Speaking of halos, I am reminded of a row of saints which occupied the niches above the altar in a certain theological seminary. They were made of marble, and each had upon his head a halo, also of marble, and resembling nothing so much as a large dinner plate. Winter had a disastrous effect upon these halos. The frost cracked them and they fell off. A sudden drop in temperature during the night meant that one or more of those blessed saints would be minus a nimbus in the morning.

There are those who would like to see what effect a frost would have on the halo of Henry Ford. They want to know the worst, not to “have it over,” but to help “put it over.” If there be such among my readers they are going to be more or less disappointed. I was accused not long ago by a prominent labor leader of being more responsible than any other one man for creating the Ford halo. He thought I ought to try to take it off. But why waste one’s time? Once a halo is on, the wearer of it is the only one who can take it off. If he proves himself worthy, the halo sticks; if otherwise, the halo fades of itself. For the present, I am interested neither in taking the Ford halo off, nor in holding it on.

The truth is, as everybody knows, there is some clay in every popular idol. There is some in Henry Ford.

It would be possible to write a book made up entirely of adverse criticism of both himself and his company, every word of which would be true, and yet the book on the whole would be utterly false and misleading, as false and misleading as one of unstinted praise.

There are things that are laudable in both the man and his company, and there are things in both which it is a pity are there. I shall endeavor to state the truth in a frank and friendly manner. It may be that such publicity will tend to eliminate some of the things which cause us to mingle regret with our admiration.

On the return journey from Europe above referred to I found it necessary to make a very frank criticism of certain ideas advanced by Mr. Ford. It was to the effect that if he stuck to the things he knew, and let those alone about which his training had not qualified him to venture an opinion, he would avoid placing himself in a foolish position. The criticism stuck. I have heard him refer to it many times since. The last time he mentioned the matter in my presence he added, “And I have come to the conclusion that the best friend one has is the man who tells him the truth.” I hope he will receive the critical portion of these pages in the same spirit. They are meant to help, for I would like to see that halo stick.

But as for halos,—they may be left to the biting frosts of time. History, in spite of Mr. Ford’s gibes at her, will ultimately put him in the niche in which he belongs, with or without a halo according to his deserts.

CHAPTER II—THE ART OF SELF-ADVERTISING

THE ordinary mortal is content to hitch his wagon to a star. This is a sport too tame for Henry Ford. He prefers to hang on to the tail of a comet. It is less conventional, more spectacular and furnishes more thrills.

Mr. Ford seems to love sensations, to live in them and to be everlastingly creating them, jumping from one to another. And many of his sensational acts and utterances are so clever that the world looks on with something more than amusement. In spite of the fact that he has come near making a clown of himself on more than one occasion, the audience, for the most part, continues to watch him with wonder and admiration. He has been right so many times in industrial matters, done so many admirable and worthwhile things, that we are inclined to forget the times he has been wrong or foolish.

I suppose that an acrobat with a net under him takes risks that he would not take if he were looking down on the bare hard earth. In like manner, I suppose, the fact that one has under him several hundred millions to fall back on renders him more or less indifferent to a tumble. He can afford to try stunts he would otherwise hesitate to undertake. But whatever the reason, Henry Ford appears to be drawn to the limelight as a moth to a candle. If he comes out slightly singed, as in the case of the Peace Ship and the Tribune trial, he nevertheless comes gaily and boldly back to flutter around a Semitic or other candle. One cannot but marvel at the continuance of the public’s patience, interest and faith.

There is a popular interest in Henry Ford which is not difficult of explanation. The world’s chief interest is, and always has been, in successful men. It does not matter much in what field their achievement lies, so long as they have achieved. Captain Kidd, Jesse James, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Sullivan, Dempsey, Samson, Goliath of Gath, Napoleon, Washington, Grant, Foch, Lincoln, Homer, Shakespeare, Angelo, Wagner, Charlie Chaplin, Rockefeller, Morgan, Schwab, Carnegie, Edison, Ford—pirates, outlaws, four-base hitters, prize fighters, soldiers, statesmen, writers, painters, composers, movie stars, financiers, inventors—we are interested in them, if only they are a success. And we want to know all there is to know about them.

Henry Ford is among the top-notchers in the field of achievement along industrial lines. He is in the class of highly successful men, and he shares in the interest which the world gives to this class as a whole.

But more of popular interest attaches to Mr. Ford than to any other man of his class. He is the most widely known, the most talked-of, and—among the masses—the most popular man in private life today, and has been for the past ten years. How account for it?

It is said of him that he is always doing sensational things—some wise, some foolish; that, he is the best self-advertiser of the age; that the spotlight cannot be shifted fast enough to keep him out of it. Henry Ford does do sensational things. In addition to that he frequently makes sensational attempts to do things he is unable to do. And from the self-advertising point of view, a sensational attempt is almost always as valuable for immediate purposes as a sensational achievement. The man who proposes to ride Niagara Falls in a barrel has several weeks before the event in which to enjoy the publicity that will be given him, and to exhibit the barrel for a consideration. If he survives his sensational undertaking, the barrel will be of still greater value to him. If he should not chance to come up after his spectacular plunge, and it was a taste of notoriety he craved, he had what he wanted for a brief time and, presumably, died happy.

Of course, the man who insists on standing all the time in the calcium ray must expect to be put under the X-ray. And the shadows cast by these two rays are quite different.

The man who attempts to do sensational things entirely out of his sphere and beyond his power will, in time, wear down the public’s confidence in his judgment. Henry Ford is not so widely admired as he once was. Grant that a man is sincere in trying to do what he is not fitted to do, that will not prevent men mingling pity with their admiration. And pity, when too frequently aroused, is in danger of turning into a mild contempt.

Henry Ford made a spectacular attempt to end the World War. The Peace Ship brought a flood of publicity—fame or notoriety—just as one looks at it. I questioned his judgment at the time, but not his motive. And I still believe his motive back of that undertaking was a laudable one. If all the facts were known, I think it would be admitted that he did not deserve the ridicule that was heaped upon him. To me, during the early months of the war, he was a pathetic and much misunderstood figure. I endeavored to persuade him to abandon the Peace Ship project, or at least to modify his plans. His old friend, Mr. William Livingstone, and myself spent the most of the night before the expedition sailed trying to prevail upon him to abandon it. It was no use. His reply to me was, “It is right, is it not, to try to stop war?” To that I could only answer, “Yes.” “Well,” he would go on, “you have told me that what is right cannot fail.” And the answer to that, that right things attempted in the wrong way had no assurance of success, had no effect. He was following what he calls a “hunch,” and when he gets a “hunch” he generally goes through with it, be it wise or foolish, right or wrong.

But to the credit of Henry Ford it must be said that he has done sensational things...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION-HENRY FORD AN INTERPRETATION

- CHAPTER I-THE FORD HALO

- CHAPTER II-THE ART OF SELF-ADVERTISING

- CHAPTER III-A DREAM THAT CAME TRUE

- CHAPTER IV-THE FORD FORTUNE

- CHAPTER V-SOME ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS

- CHAPTER VI-MENTAL TRAITS AND CHARACTERISTICS

- CHAPTER VII-“JUST KIDS”

- CHAPTER VIII-BEHIND A CHINESE WALL

- CHAPTER IX-HENRY FORD AND THE CHURCH

- CHAPTER X-HENRY FORD, DIVES, LAZARUS AND OTHERS

- CHAPTER XI-THE FORD CHARITIES

- CHAPTER XII-THE FORD EXECUTIVE SCRAP HEAP

- CHAPTER XIII-THE FORD INDEBTEDNESS

- CHAPTER XIV-INDUSTRIAL SCAVENGERS

- CHAPTER XV-LIGHTS

- CHAPTER XVI-SHADOWS

- CHAPTER XVII-AN ELUSIVE PERSONALITY

- CHAPTER XVIII-EDSEL FORD

- CHAPTER XIX-THE SON AND HIS FATHER’S SHOES

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Henry Ford by Rev. Samuel S. Marquis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.