- 165 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

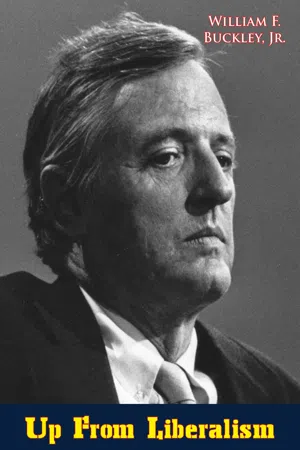

Up From Liberalism

About this book

William Frank Buckley Jr.'s third book, originally published in 1959, is an urbane and controversial attack on the manners and meaning of American Liberalism in the 1950s. His thesis is that the leading American liberals can be shown, in their speeches and statements, in the tacit premises that underlie their words and deeds, to be suffering from a long, but definable list of social and philosophical prejudices. "Up From Liberalism" examines the root assumptions of the Liberalism of his era and asks the startling question: do the actions of prominent liberalism derive from the attributes of Liberalism?

"This book of mind and heart, wit and eloquence, by the chief spokesman for the young conservative revival in this country, must be read and understood, to understand what is going on in America."—Senator Barry Goldwater

"A guide for Americans who want to stay free in a country where pressures against individual freedom are coming from every direction."—Charleston Nines & Courier

"He is at top form...clear and penetrating...A slashing attack against the thinking of today's pseudo-liberals."—Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph

"The most exciting book of the Fall."—New York Mirror

"Mr. Buckley is one of the most articulate of the critics of today's liberalism and deserves to be heard."—Washington Star

"Buckley brilliantly excoriates a philosophy he calls liberalism."—Newsweek

"A skilled debater, a trenchant stylist...a man of agile and independent mind...He belongs in the great American tradition of protest and he deserve his audience."—New York Herald Tribune

"This book of mind and heart, wit and eloquence, by the chief spokesman for the young conservative revival in this country, must be read and understood, to understand what is going on in America."—Senator Barry Goldwater

"A guide for Americans who want to stay free in a country where pressures against individual freedom are coming from every direction."—Charleston Nines & Courier

"He is at top form...clear and penetrating...A slashing attack against the thinking of today's pseudo-liberals."—Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph

"The most exciting book of the Fall."—New York Mirror

"Mr. Buckley is one of the most articulate of the critics of today's liberalism and deserves to be heard."—Washington Star

"Buckley brilliantly excoriates a philosophy he calls liberalism."—Newsweek

"A skilled debater, a trenchant stylist...a man of agile and independent mind...He belongs in the great American tradition of protest and he deserve his audience."—New York Herald Tribune

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I—THE FAILURE OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LIBERALISM

“CONSTRUCTIVE CRITICISM. The demand for constructive rather than destructive criticism (usually with an exaggerated emphasis on the first syllable of each adjective) has become one of the cant phrases of the day. It is true that under the guise of criticism mockery and hatred often vent their spite, and what professes to be a fair and even helpful analysis of a situation or policy is sometimes a malignant attack. But the proper answer to that is to expose the malignance and so point out that it is not criticism at all. Most whining for constructive rather than destructive criticism is a demand for unqualified praise, an insistence that no opinion is to be expressed or course proposed other than the one supported by the speaker. It is a dreary phrase, avoided by all fair-minded men.”—From: A Dictionary of Contemporary American Usage by Bergen Evans and Cornelia Evans (RANDOM HOUSE, 1957)

The Liberal—IN CONTROVERSY

The Mania

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT the folklore of American Liberalism. I am very much surprised that so little of an orderly kind has been written about the American Liberal. A good library will direct you to a vast literature on the history of Liberalism, and every year or so a new book is published which presents itself as a hot-off-the-press examination of contemporary Liberalism. But one who reads the literature, and then turns to look at the land he lives in, will have a difficult time reconciling the lofty presumptions of unleavened Liberalism with the behavior and attitudes of Liberalism’s most conspicuous exponents.

There are always such discrepancies, let us hasten to grant—the bigoted churchman, the protectionist free enterpriser, the provincial internationalist, the licentious moralist—all of them well-known anomalies, widely commented Upon in our literature. Yet for reasons that are persisting but hard to pin down, there is no sociological study of American Liberalism. Is this because no Middletown could be written about the world of the Americans for Democratic Action? Or is it that the topic—the behavior and thought pattern of the opinion-makers of the most powerful country on earth—does not merit such treatment? Why should it be easier to understand the mind of Nikita Khrushchev than that of Chester Bowles?

A reviewer of my most recent book charged that it is clear from my use of the word “Liberal” that I could only have in mind the clientele of the Nation Magazine. I am encouraged that that reviewer, writing in a prominent Liberal daily, tacitly conceded that the Nation-reader has recognizable spots, a concession that is very late in coming. I detect a little discomfort, here and there, when the word “Liberal” is bandied about. Many people are not satisfied to be unique merely in the eyes of God, and spend considerable time in flight from any orthodoxy. Some make a profession of it, and end up, as for instance the critic Dwight Macdonald has, with an intellectual and political career that might have been painted by Jackson Pollock. But even discounting that grouping, an increasing number of persons are visibly discomfited by the appellation “Liberal,” and it can only be because there is in fact perceptible, even though the proper prisms for viewing it have not been ground, a Liberal virus—and a corresponding Liberal syndrome; things, surely, that should be written about.

The Liberals I shall refer to in this book are men and women who are clearly associated with the Liberal movement in America, however often they seem to be deviating to right or left from the mainstream. Because Liberalism has no definitive manifesto, one cannot say, prepared to back up the statement with unimpeachable authority, that such-and-such a man or measure is “Liberal.” But one can say that Mrs. Roosevelt is a Liberal, and do so confident that no one will contradict him. And say the same of Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Joseph L. Rauh and James Wechsler and Richard Rovere and Alan Barth and Agnes Meyer and Edward R. Murrow and Chester Bowles, Hubert Humphrey, Averell Harriman, Adlai Stevenson, Paul Hoffman. The New Republic is Liberal, so is the Washington Post, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Minneapolis Tribune; much of the New York Times, all of the New York Post. These men and women and institutions share premises and attitudes, show common reactions, enthusiasms and aversions, and display an empirical solidarity in thought and action, on the strength of which society has come to know them as “Liberals.” They are men and women who tend to believe that the human being is perfectible and social progress predictable, and that the instrument for effecting the two is reason; that truths are transistory and empirically determined; that equality is desirable and attainable through the action of state power; that social and individual differences, if they are not rational, are objectionable, and should be scientifically eliminated; that all peoples and societies should strive to organize themselves upon a rationalist and scientific paradigm.

One asks: are there characteristic idiosyncrasies of the Liberal mind at work? I think there are. Here we must draw an important distinction. Some minds are not trained to think logically under any circumstances. Miss Dorothy Sayers was much concerned about this as a characteristic failing of our generation which has nothing to do with ideological affiliation.{2} I shall not, here, be contending what Miss Sayers, whose dismay is shared by many observers of American education, contends, namely that the faculty for logical thought is a skill of which the entire contemporary generation has been bereft; I note, but do not press, the point.

I shall be assuming that in most respects the Liberal ideologists are, like Don Quixote, wholly normal, with fully developed powers of thought, that they see things as they are, and live their lives according to the Word; but that, like Don Quixote, whenever anything touches upon their mania, they become irresponsible. Don Quixote’s mania was knight-errantry. The Liberal’s mania is their Ideology.{3} Deal lightly with any precept of knight-errantry, and you might find, as so many innocent Spaniards did, the Terror of La Mancha hurtling toward you. Cross a Liberal on duty, and he becomes a man of hurtling irrationality.

The problems of demonstration are considerable, since I level my charge not merely at specific individuals, but at the disciples, en bloc, of a politico-philosophical movement. One can say, “Disciples of Communism, en bloc, follow the Moscow line.” That is a responsible generalization, unaffected by the fact of schismatic flare-ups or deviationist sallies. Such a statement is not supported by counting the noses of all the Communists who have switched their positions to harmonize with a change in the Moscow line. This type of census is impractical. Rather, one observes the shifting pronouncements of Communist spokesmen and their house organs, and waits to see if substantial opposition develops from the rank and file. If it does not, the rank and file can be assumed to have complied—whether by internal assent or as a matter of discipline is irrelevant.

If one sets out to show that a religious sect is corrupt, it does not suffice to point to a member of that sect who has been caught channeling money from the collection plate to his mistress. He is proved corrupt, but not, yet, the movement. Suppose, then, one approaches the delinquent’s co-religionists and asks them for an expression of opinion on the behavior of their brother. If they show a marked indifference to it, if they actively defend him, if they continue to countenance or even move him up the ladder of their hierarchy, more and more one is entitled to generalize—as in passing judgment on the union of Mr. James Hoffa—that the organization is corrupt.

How does one, then, go about demonstrating that the mania I speak of afflicts the spokesman of a contemporary political movement? By these means, I suggest: by citing instances of intellectual or moral irresponsibility which, taken by themselves, would serve merely to demonstrate the limitations of the person under consideration; but which take on a much broader meaning if—and here is the critical distinction I make here and in other chapters in this book—the subject’s publicly observed irresponsibilities do not have the effect of blemishing his public reputation among his factional associates.

I offer below a small cluster of illustrations, all but one in some way turning on the controversy surrounding Senator McCarthy. I go back several years for good reason. Whatever Senator McCarthy did, he brought Liberalism to a boil. Everything he did that was good, everything that he did that was bad, added together, does not have the residual sociological significance for our time of what his enemies were revealed as seeing fit to do in opposing him. Let us concede that if ever a man in America crossed the Liberal ideology, or at least gave the impression of doing so, McCarthy did, which is why the McCarthy years are a cornucopia for the sociologist doing research for a Middletown on American Liberalism, and for the psychiatrist looking for what I have called his syndrome.

The controversies in which Senator McCarthy was engaged have no relevance whatever to what follows, whose meaning is the same for those who hated, and those who loved McCarthy. It is not necessary to have a commitment to any particular cosmology to enter into a spirited discussion of the political and intellectual controversy touched off by Galileo: unnecessary to believe or disbelieve what Socrates was teaching the youth of Athens, in order to believe or disbelieve that the Court did him justice. I beg the reader who is anti-McCarthy to bear this in mind in the next few pages, during which he will be face to face with the incubus; and I caution the reader who is pro-McCarthy (the Liberals can never quite believe such a phenomenon exists) not to lose sight of the ball, which though it may have been thrown by Joe McCarthy, or caught by Eleanor Roosevelt, has nothing to do with the scoring of the game.{4}

1.

There is, to begin with, Mrs. Roosevelt herself.

Some years ago, after Mrs. Roosevelt had written a column likening McCarthyism to Hitlerism, I suggested on a television program that symbolic of the sluggishness of Liberal-directed anti-Communism was the fact that should Eleanor Roosevelt happen upon Senator McCarthy at a cocktail party she would probably refuse to shake Vishinsky’s hand at the same party. (Andrei Vishinsky was then head of the Soviet delegation in New York.) A day or two later, a reporter brought the remark to her attention. What about it? he asked. Mrs. Roosevelt answered emphatically that she would shake hands with both Vishinsky and McCarthy at any future social affair, that in point of fact she once had shaken McCarthy’s hand (the memory was evidently seared upon her mind); and that, of course, she had seen a great deal of Vishinsky while she was with the UN, hammering out the Declaration of Human Rights.

Still later, in her question and answer column in the Woman’s Home Companion, the question appeared, “In a recent column you defended your right to shake hands with Mr. Vishinsky, and Senator McCarthy. Would you also have felt it was right to shake hands with Adolf Hitler?” To which Mrs. Roosevelt answered, “In Adolf Hitler’s early days I might have considered it, but after he had begun his mass killings I don’t think I could have borne it.”

I suggest Mrs. Roosevelt’s philosophy of hand-shaking does not emerge from the data. If we were to set up a syllogism, here is how it would look:

Proposition A: E. R. will not shake hands with those who are guilty of mass killings.

Proposition B: E. R. will shake hands with Andrei Vishinsky.

Conclusion: Vishinsky is not guilty of mass killings.{5}

But Vishinsky was guilty of mass killings, and surely Mrs. Roosevelt knew that. Indeed, that was a principal revelation of the famous John Dewey Commission of 1939, whose findings on the nature of Stalin’s purge trials, at which Vishinsky served as chief prosecutor, settled forever the matter of Vishinsky’s blood guilt. What could she have been trying to say? That there were differences between Hitler and Vishinsky of the type one takes stock of before extending one’s hand? The only explanation Mrs. Roosevelt attempted hangs on the phrase “after Hitler had begun his mass killings...”—then she could not bear to shake his hand. But as mass executioner Vishinsky reached the apex of his career ten years before Mrs. Roosevelt found it bearable to talk with him, and even to work with him, at the United Nations in search of a mutually satisfactory declaration of human rights. A comparable activity: chatting with Goebbels about a genocide agreement.

The preceding example is one of any number, easily culled from her column during those years, that demonstrate Mrs. Roosevelt’s lack of intellectual rigor. (I grant that following Mrs. Roosevelt in search of irrationality is like following a burning fuse in search of an explosive; one never has to wait very long.) It will be objected that generalizations about the limitations of the Liberal mind based on anything that she writes or says are invalid. I disagree, for the reasons I have stressed. The intellectual probity of a person is measured not merely by what comes out of him, but by what he puts up with from others.

Where are the voices of dismay, where Mrs. Roosevelt is concerned?

Mrs. Roosevelt is a leading mouthpiece of contemporary Liberalism, and the fact that she is one of history’s truly remarkable women has nothing whatever to do with the fact that she is also a fountain of confusion. In quoting from her I do not pretend to be quoting from a first-ranking Liberal scholar or philosopher; but I do ask why first-ranking Liberal scholars and philosophers and thoughtful laymen countenance her on her terms (she is a Sage). It may be because a) they are aware that Mrs. Roosevelt’s close personal and political association with her husband have invested her with a glamor that is highly utilitarian, or because b) (this explanation is both more plausible and more charitable), Mrs. Roosevelt’s polemical life is lived right in the heart of the Liberal mania, with the result that, themselves bereft of their senses, they are incapable of recognizing that Mrs. Roosevelt is bereft of hers.{6}

2.

Senator Ralph Flanders, a moralistic Republican from Vermont, rises on the floor of th...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- INTRODUCTION

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- I-THE FAILURE OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LIBERALISM

- II-THE CONSERVATIVE ALTERNATIVE

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Up From Liberalism by William F. Buckley Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.