![]()

Chapter I—Precious Paper

Everywhere in the world, people have found that in the conduct of their business and financial affairs they gain efficiency and convenience by using symbols or tokens of their rights, powers or possessions. In technologically advanced areas of the world, these symbols generally take the form of paper documents. They may be as small as postage stamps or as large as coupon bonds. They may be as specialized as gold certificates or as widely used as paper money and travelers cheques.

Whatever their names or purposes, these documents share the feature of having a generally accepted worth equivalent to whatever they are stated to represent. For that reason bank notes, stamps, corporate, state and municipal bonds, stock certificates and other types of securities for listing on the exchanges, travelers cheques, letters of credit and similar forms of commercial paper are conveniently referred to as documents of value.

The successful use of such documents rests upon the confidence which can be placed in their validity. The cost of manufacturing a document of value is very small when compared with what it may represent, and its intrinsic value is practically nil. Yet every day hundreds of millions of dollars are paid with confidence in exchange for these special pieces of paper.

If there ever should arise ground for general doubt of the validity of documents of value, whether bank notes, stock certificates, bonds, travelers cheques or stamps, the ensuing paralysis of economic life would be appalling. That is why a world which is divided on so many of its other beliefs agrees on the importance of maintaining confidence in documents of value. Throughout the world stringent penalties are imposed on convicted counterfeiters. In a more forthright age, a century and a half ago, bank notes in English-speaking countries frequently bore the words “‘Tis Death to Counterfeit,” and statutes made the threat a real one. In the present-day United States the Federal Government has one special organization, the Secret Service, with the prevention and detection of counterfeiting as one of its two dudes, the other being the protection of the President of the United States, members of his family, the President-elect, and the Vice President at his request.

But the use of police power alone cannot prevent a serious amount of counterfeiting, even with death and torture as penalties. The evidence of history on this point is clear. A more important safeguard, therefore, is the principle that documents of value must be made so difficult to copy that to do so is unattractive to those undeterred by moral considerations or the threat of punishment.

The task of making documents that defy counterfeiters is the province of what is known as the bank note industry. It is a small industry by comparison with many others. Yet its products probably enter into the lives of more individual men and women throughout the world than do those of any other industry.

![]()

Exacting Demands of Bank Note Printing

Security printing is different from most other activities in many respects, but chiefly in that its products represent values which are hundreds, even thousands, of times their cost. Caution, aloofness and secrecy are therefore inescapable, as are many unusual business policies. For example, no customer, whether corporation or government, may obtain possession of the engravings from which its documents have been printed. As another example, all of the important scientific advances of the last century and a half that have related to the graphic arts or visual reproduction have had to be considered first as potentially dangerous weapons in the hands of counterfeiters, and only then as possibly useful adjuncts to the industry. The invention of the camera, for instance, required prompt countermeasures, and the invention of film and filter combinations, by which a camera could select a single color and ignore others, demanded another change in strategy. There would be considerable truth in the statement that, while other industries direct their research to finding easier ways to make their products, the conscientious security printer seeks to find more difficult ways. There are no open-house nights in a money factory, and no free samples!

A more subtle difference is this: while the general tendency of industry is to eliminate the personal characteristics of individual craftsmen, bank note engraving carefully continues them, even stresses them, because, despite all technological advances, the counterfeiter’s most baffling problem is the unique personality of the artist which the engraving process transmits directly to the document.

Since no photography enters into its creation, an engraved document cannot be duplicated by it. (A camera can of course make a picture of an engraved document, but that is very different from duplicating it—a camera can make a picture of a car, but it cannot make a kitten.) Therefore another engraving would be necessary, which under comparative examination could not fail to reveal a personal touch different from the original.

Beyond defeating counterfeiters from the standpoint of expert examination of documents, every effort is put forth to make their spurious products apparent even to cursory or non-expert examination. The most advanced achievements of the industry have been strikingly successful in both respects.

![]()

Three Methods of Printing

Security printing has its technicalities, which are an integral part of its history. A few terms and principles can be explained here better than in the chapters which follow.

There are three fundamentally different ways to make printed impressions on paper. To see how they differ, we can imagine a man sitting at a table with sheets of paper, ink (not liquid, but thick like tooth paste) and a piece of some smooth washable material, say a piece of linoleum. He wants to print an “X” on each sheet of paper.

The man has three choices:

(a) He can mark an “X” on the linoleum with ink, then press each sheet of paper in turn against it, renewing the ink on his “X” as necessary. This is surface printing, of which the principal commercial example is lithography. In place of our amateur’s linoleum, in this process the paper is pressed against a stone or rubber surface, depending upon whether it is direct or offset lithography.

(b) He may use a knife to cut down his linoleum everywhere except where his “X” is marked. The “X” will then stand higher than the material around it. When he runs an inked roller over his work, only the elevated “X” surface will be coated with the ink. A sheet pressed down on his work will touch the elevated surface only, and will be marked with the “X.” This was originally known as cameo printing, but it is more popularly called letterpress. It is the method of the traditional printing industry, and also of the woodcut and the humble rubber stamp. The material used is generally a lead alloy, zinc or copper.

(c) He may, however, use his knife for a different purpose—to cut an “X” into the surface of the linoleum, the way he once carved initials into the surface of his school desk. Next he coats the linoleum with ink, then thoroughly wipes the ink from the level surface, leaving it only in the recessed cuts. When a sheet of paper is pressed down firmly on the linoleum and into the carved “X,” this ink will adhere to it and be pulled out of the recess when the sheet is withdrawn, so that it remains as an “X” with appreciable thickness on the paper. This is intaglio printing. Typical examples include security printing, other forms of engraving such as that used for fine wedding announcements, and gravure, which is the photo-mechanical version of intaglio printing. The material used is steel, copper or zinc.

In this book, the text is an example of letterpress printing, the illustrations on text pages are printed in gravure. The map is printed by lithography. The inserted display pages are intaglio printed from steel engravings.

![]()

American Bank Note—the Trail Blazer

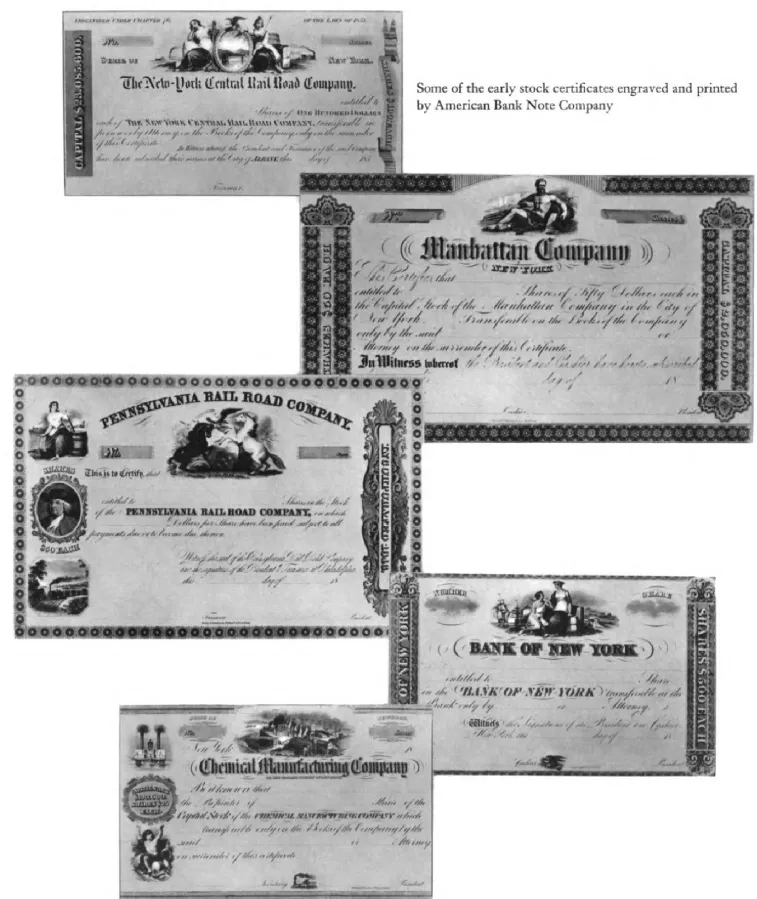

Because of its institutional position and the service it renders throughout the free world, and because its roots trace directly back to the early days of this country, the story of American Bank Note Company is scarcely separable from the story of security printing as a craft and an industry. All significant technical advances in the field have been closely identified with the pioneer names which are embedded in the Company’s history, and its standards have been a worldwide influence.

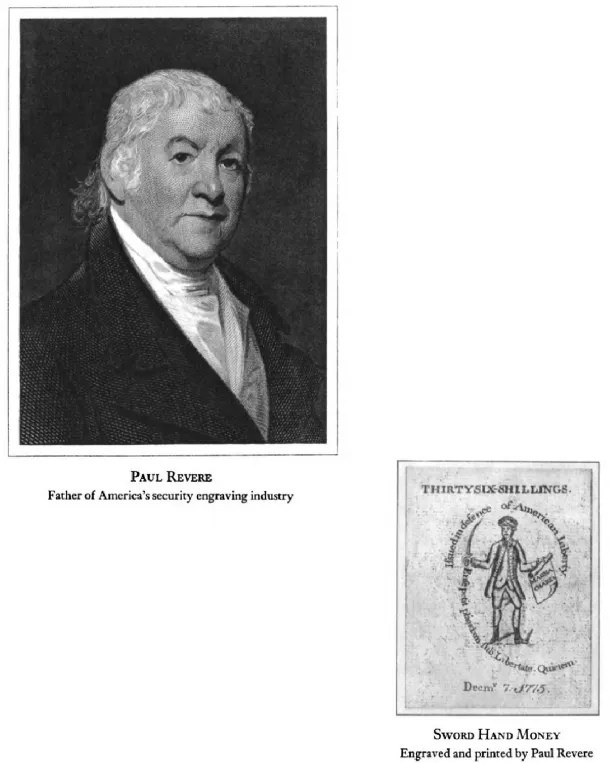

The history of security printing has its share of stirring incidents. There was the time Paul Revere cut up one of his precious engraved copper plates in order to make a new plate with which to manufacture independent America’s first money. There was another time, in early nineteenth-century England, when a group of leading citizens, appalled by the number of pitiful wretches their nation had to hang every year to discourage counterfeiting, met to consider the problem. The deliberations of this group will be referred to subsequently. There was the issuing of “Continental currency” in our War of Independence. And there was the New York postmaster who, after the Congress decided on prepaid mail by means of stamps, ordered his stamps from a bank note printing company in his neighborhood, the first provisional stamps in the United States.

On a larger scale, and continuing into the present, the story of security printing is a part of the great industrial growth of America, in which the spreading ownership of millions of stock certificates and bonds played and continues to play an essential part. Finally, the story of security printing includes the engraved postage stamps of the United Nations, issued by no government but honored by all, token of men’s desire to have a more peaceful and prosperous world.

![]()

Chapter II—The Early Days—1795-1823

American Bank Note Company traces its beginning back to 1795. The place was Philadelphia, and the man was Robert Scot.

The year 1795 was the midpoint of the important first decade of the American Constitution, when the existence of a long-needed orderly government permitted an expansion of the economy to meet pent-up demands which could not be satisfied under previously existing political conditions. One of the most pressing needs was for banking service and circulating bank notes, and this need resulted in the development of the bank note printing industry.

Even in the decade of its birth the young industry had a long ancestry. Here in the new world there had been paper money in use, in one form or another, for more than one hundred years. A private bank in Massachusetts was issuing circulating notes in 1681, and in 1690 the Massachusetts Colony itself issued bills of credit, which circulated as money, to pay the cost of a military expedition against French-held Quebec.

This Massachusetts note issue of 1690 was studied by the organizers of the Bank of England, which was established in 1694 and issued its first notes shortly afterward.

The first note engraver of the American colonies whose name has been preserved was one “Jno. Conny.” He rendered a statement to the Massachusetts colonial government, bearing a 1702 date, for “engraving three bills of credit.”

Counterfe...