eBook - ePub

Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy

A Systematic Individual and Social Psychiatry

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1961, this book outlines a new, unified system of individual and social psychiatry that were introduced in the United States around that time with remarkable success in various hospitals and other psychiatric establishments. Essentially designed for group therapy, this approach is now used by institutions, group workers, and in private practice with neurotics, psychotics, sexual psychopaths, psychosomatic cases, and adolescents.

Transactional analysis begins its program by initiating the individual patients into the theory upon which the treatment is based. First attaining a measure of self-knowledge through private sessions with the analyst, the patient then meets with other patients in group therapy, participating in a series of personally meaningful relation-ships in which he becomes increasingly aware of the cause and nature of his illness, preparing at the same time to overcome it.

"A comprehensive method of treatment that has no precedent in its concreteness of structure without at the same time diminishing the dynamic quality of the treatment....No one to my knowledge has presented such a new approach."—Dr. Milton Schwebel, Professor of Education, New York University

Transactional analysis begins its program by initiating the individual patients into the theory upon which the treatment is based. First attaining a measure of self-knowledge through private sessions with the analyst, the patient then meets with other patients in group therapy, participating in a series of personally meaningful relation-ships in which he becomes increasingly aware of the cause and nature of his illness, preparing at the same time to overcome it.

"A comprehensive method of treatment that has no precedent in its concreteness of structure without at the same time diminishing the dynamic quality of the treatment....No one to my knowledge has presented such a new approach."—Dr. Milton Schwebel, Professor of Education, New York University

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy by Dr. Eric Berne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I—Psychiatry of the Individual and Structural Analysis

CHAPTER TWO—The Structure of Personality

MRS. PRIMUS, a young housewife, was referred by her family physician for a diagnostic interview. She sat tensely for a minute or two with her eyes downcast, and then she began to laugh. A moment later she stopped laughing, looked stealthily at the doctor, then averted her eyes again, and once more began to laugh. This sequence was repeated three or four times. Then rather suddenly she stopped tittering, sat up straight in her chair, pulled down her skirt, and turned her head to the right. After observing this new attitude for a short time, the psychiatrist asked her if she were hearing voices. She nodded without turning her head, and continued to listen. The psychiatrist again interrupted to ask her how old she was. His carefully calculated tone of voice successfully captured her attention. She turned to face him, pulled herself together, and answered his question.

Following this, she answered a series of other pertinent questions concisely and to the point. Within a short time, enough information was obtained to warrant a tentative diagnosis of acute schizophrenia, and to enable the psychiatrist to piece together some of the precipitating factors and some of the gross features in her early background. After this, no further questions were put for a while, and she soon lapsed into her former state. The cycle of flirtatious tittering, stealthy appraisal, and prim attention to her hallucinations was repeated until she was asked whose voices they were and what they were saying.

She replied that it seemed to be a man’s voice and that he was calling her awful names, words she had never heard before. Then the talk was turned to her family. Her father she described as a wonderful man, a considerate husband, a loving parent, well-liked in the community, and so forth. But it soon came out that he drank heavily, and then he was different. He used bad language. She was asked the nature of the bad language. It then occurred to the patient that she had heard him use some of the same epithets that the hallucinated voice was using.

This patient rather clearly exhibited three different ego states. These were distinguished by differences in her posture, manner, facial expression, and other physical characteristics. The first was characterized by tittering coyness, quite reminiscent of a little girl at a certain age; the second was primly righteous, like that of a schoolgirl almost caught in some sexual peccadillo; in the third, she was able to answer questions like the grown-up woman that she was, and was able to demonstrate that in this state her understanding, her memory, and her ability to think logically were all intact.

The first two ego states had an archaic quality in that they were appropriate to some former stage of her experience, but were inappropriate to the immediate reality of the interview. In the third, she showed considerable skill in marshaling and processing data and perceptions concerning her immediate situation: what can easily be understood as “adult” functioning, something that neither an infant nor a sexually agitated school-girl would be capable of. The process of “pulling herself together,” which was activated by the business-like tone of the psychiatrist, represented the transition from the archaic ego states to this adult ego state.

The term “ego state” is intended merely to denote states of mind and their related patterns of behavior as they occur in nature, and avoids in the first instance the use of constructs such as “instinct,” “culture,” “superego,” “animus,” “eidetic,” and so forth. Structural analysis postulates only that such ego states can be classified and clarified, and that in the case of psychiatric patients such a procedure “is good.”

In seeking a framework for classification, it was found that the clinical material pointed to the hypothesis that childhood ego states exist as relics in the grown-up, and that under certain circumstances they can be revived. As already noted in the introduction, this phenomenon has been repeatedly reported in connection with dreams, hypnosis, psychosis, pharmacological intoxicants, and direct electrical stimulation of the temporal cortex. But careful observation carried the hypothesis one step further, to the assumption that such relics can exhibit spontaneous activity in the normal waking state as well.

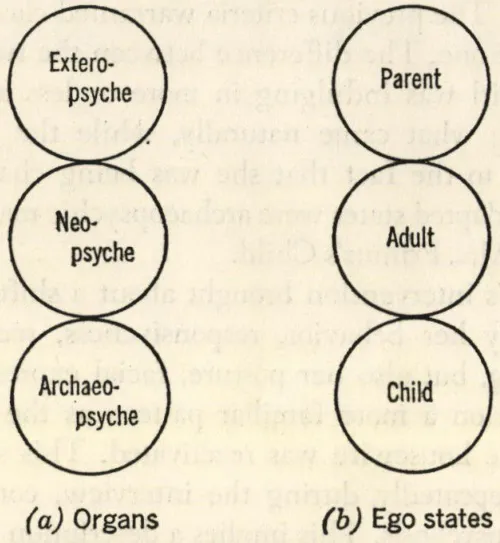

FIGURE 1

What actually happened was that patients could be observed, or observed themselves, shifting from one state of mind and one behavior pattern to another. Typically, there was one ego state characterized by reasonably adequate reality-testing and rational reckoning (secondary process), and another distinguished by autistic thinking and archaic fears and expectations (primary process). The former had the quality of the usual mode of functioning of responsible adults, while the latter resembled the way very young children of various ages went about their business. This led to the assumption of two psychic organs, a neopsyche and an archaeopsyche. It seemed appropriate, and was generally acceptable to all individuals concerned, to call the phenomenological and operational manifestations of these two organs the Adult and the Child, respectively.

Mrs. Primus’s Child manifested herself in two different forms. The one which predominated in the absence of distracting stimuli was that of the “bad” (sexy) girl. It would be difficult to conceive of Mrs. Primus, in this state, undertaking the responsibilities of a sexually mature woman. The resemblance of her behavior to that of a girl child was so striking that this ego state could be classified as an archaic one. At a certain point, a voice perceived as coming from outside herself brought her up short, and she shifted into the ego state of a “good” (prim) little girl. The previous criteria warranted classifying this state also as an archaic one. The difference between the two ego states was that the “bad” girl was indulging in more or less autonomous self-expression, doing what came naturally, while the “good” girl was adapting herself to the fact that she was being chastised. Both the natural and the adapted states were archaeopsychic manifestations, and hence aspects of Mrs. Primus’s Child.

The therapist’s intervention brought about a shift into a different system. Not only her behavior, responsiveness, reality-testing, and mode of thinking, but also her posture, facial expression, voice, and muscle-tone took on a more familiar pattern as the Adult ego state of the responsible housewife was reactivated. This shift, which was brought about repeatedly during the interview, constituted a brief remission of the psychosis. This implies a description of psychosis as a shift of psychic energy, or, to use the commonly accepted word, cathexis, from the Adult system to the Child system. It also implies a description of remission as the reversal of this shift.

The derivation of the hallucinated voice with its “unfamiliar” obscenities would have been evident to any educated observer, in view of the change it brought about in the patient’s behavior. It remained only to confirm the impression, and this was the purpose of turning the discussion to the patient’s family. As anticipated, the voice was using the language of her father, much to her own surprise. This voice belonged to the exteropsychic, or parental system. It was not the “voice of her Superego,” but the voice of an actual person. This emphasizes the point that Parent, Adult, and Child represent real people who now exist or who once existed, who have legal names and civic identities. In the case of Mrs. Primus, the Parent did not manifest itself as an ego state, but only as a hallucinated voice. In the beginning, it is best to concentrate upon the diagnosis and differentiation of the Adult and the Child, and consideration of the Parent can be profitably postponed in clinical work. The activity of the Parent may be illustrated by two other cases.

Mr. Segundo, who first stimulated the evolution of structural analysis, told the following story:

An eight-year-old boy, vacationing at a ranch in his cowboy suit, helped the hired man unsaddle a horse. When they were finished, the hired man said: “Thanks, cowpoke!”, to which his assistant answered: “I’m not really a cowpoke, I’m just a little boy.

The patient then remarked: ‘That’s just the way I feel. I’m not really a lawyer, I’m just a little boy.” Mr. Segundo was a successful court-room lawyer of high repute, who raised his family decently, did useful community work, and was popular socially. But in treatment he often did have the attitude of a little boy. Sometimes during the hour he would ask: “Are you talking to the lawyer or to the little boy?” When he was away from his office or the court-room, the little boy was very apt to take over. He would retire to a cabin in the mountains away from his family, where he kept a supply of whiskey, morphine, lewd pictures, and guns. There he would indulge in child-like fantasies, fantasies he had had as a little boy, and the kinds of sexual activity which are commonly labeled “infantile.”

At a later date, after he had clarified to some extent what in him was Adult and what was Child (for he really was a lawyer sometimes and not always a little boy), Mr. Segundo introduced his Parent into the situation. That is, after his activities and feelings had been sorted out into the first two categories, there were certain residual states which fitted neither. These had a special quality which was reminiscent of the way his parents had seemed to him. This necessitated the institution of a third category which, on further testing, was found to have sound clinical validity. These ego states lacked the autonomous quality of both Adult and Child. They seemed to have been introduced from without, and to have an imitative flavor.

Specifically, there were three different aspects apparent in his handling of money. The Child was penurious to the penny and had miserly ways of ensuring pennywise prosperity; in spite of the risk for a man in his position, in this state he would gleefully steal chewing gum and other small items out of drugstores, just as he had done as a child. The Adult handled large sums with a banker’s shrewdness, foresight, and success, and was willing to spend money to make money. But another side of him had fantasies of giving it all away for the good of the community. He came of pious, philanthropic people, and he actually did donate large sums to charity with the same sentimental benevolence as his father. As the philanthropic glow wore off, the Child would take over with vindictive resentfulness toward his beneficiaries, followed by the Adult who would wonder why on earth he wanted to risk his solvency for such sentimental reasons.

One of the most difficult aspects of structural analysis in practice is to make the patient (or student) see that Child, Adult, and Parent are not handy ideas, or interesting neologisms, but refer to phenomena based on actual realities. The case of Mr. Segundo demonstrates this point fairly clearly. The person who stole chewing gum was not called the Child for convenience, or because children often steal, but because he himself stole chewing gum as a child with the same gleeful attitude and using the same technique. The Adult was called the Adult, not because he was playing the role of an adult, imitating the behavior of big men, but because he exhibited highly effective reality-testing in his legal and financial operations. The Parent was not called the Parent because it is traditional for philanthropists to be “fatherly” or “motherly,” but because he actually imitated his own father’s behavior and state of mind in his philanthropic activities.

In the case of Mr. Troy, a compensated schizophrenic who had had electric shock treatment following a breakdown during naval combat, the parental state was so firmly established that the Adult and the Child rarely showed themselves. In fact, he was unable at first to understand the idea of the Child. He maintained a uniformly judgmental attitude in most of his relationships. Manifestations of childlike behavior on the part of others, such as naiveté, charm, boisterousness, or trifling were especially apt to stimulate an outburst of scorn, rebuke, or chastisement. He was notorious in the therapy group which he attended for his attitude of “Kill the little bastards.” He was equally severe toward himself. His object, in group jargon, seemed to be “to keep his own Child from ever sticking his head out of the closet.” This is a common attitude in patients who have had electric shock treatment. They seem to blame the Child (perhaps rightly) for the “beating” they have taken; the Parent is highly cathected, and, often with the assistance of the Adult, severely suppresses most childlike manifestations.

There were some curious exceptions to Mr. Troy’s disapproving attitude. In regard to heterosexual irregularities and alcohol, he behaved like an all-wise benevolent father, rather than a tyrant, freely giving all the young ladies and men-about-town the benefit of his experience. His advice, however, was prejudicial and based on banal preconceptions which he was quite unable to correct even when he was repeatedly proven wrong. It was no surprise to learn that as a child he had been scorned or beaten by his father for occasional exhibitions of naiveté, charm, and boisterousness, or trifling, and regaled with stories of sexual and alcoholic excesses. Thus his parental ego state, which was protectively fixated, reproduced his father’s attitudes in some detail. This fixated Parent allowed no leeway for either Adult or Child activities except in the spheres where his father had been skillful or self-indulgent.

The observation of such fixated personalities is instructive. The constant Parent, as seen in people like Mr. Troy; the constant Adult, as seen in funless, objective scientists; and the constant Child (“Little old me”) often exemplify well some of the superficial characteristics of these three types of ego states. Some professionals earn a living b...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- TABLE OF FIGURES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I-Psychiatry of the Individual and Structural Analysis

- PART II-Social Psychiatry and Transactional Analysis

- PART III-Psychotherapy

- PART IV-Frontiers of Transactional Analysis

- APPENDIX-A Terminated Case With Follow-Up

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER