- 295 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

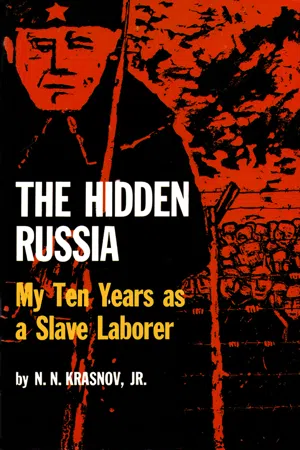

The Hidden Russia, first published in 1960, is a detailed recounting of the author's ten-years as a political prisoner inside the prisons and slave labor camps of the former Soviet Union. From the mock-trials and cells of the infamous Lubyanka, to the freezing boxcars and inhuman conditions, beatings and deprivations of the Siberian camps, Nikolai Krasnov paints a bleak picture of daily life in the Russian prison system established by the Communists. In the freezing mud huts of the Siberian Correctional Labor Camps Krasnov learned that hunger and brutality can reduce inmates as well as their slave masters to a common denominator of slovenly bestiality where "crime in the labor camps exceeds all dimensions." Even so, even under the most brutal conditions the literary eyes of the author were able to see some human decency. Whether jammed in the "icebox" freight car, tortured in a dreadful prison, or laboring animal-like in the muddy tundra there was for him always the memory of the love of his family. There persisted always his love of Russia. "The Russian people are strong and tough...they have survived more than one tempest...the future lies with the people not the government." Through his torture there yet gleams a poetic appreciation of Mother Russia. "Outside my window the spring sun was still smiling, the cloudless sky was like an inverted bowl of brilliant pale blue enamel. Cabbage butterflies fluttered by in pairs...

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hidden Russia by Nikolai Krasnov in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 — Betrayal at Lienz

It was spring. The sun poured down its rays. Bees hummed and birds chirped. The Alpine uplands were emerald green.

It was the spring of 1945.

I can see the bridge across the boisterous Drau River and the tidy little town of Lienz unharmed by the war, the neat little houses, the gardens, the beautiful Roman Catholic church, and the house used by the staff of General Domanov and his Cossack detachments.

At the time it seemed to all of us that the worst was behind us. To be sure the war had not ended with the freeing of Russian territory, for which many thousands of Russians had sacrificed their lives. To be sure it was not pleasant to recall the last months in Northern Italy, the campaign in Austria, the day of surrender to the English.

Perhaps things had not turned out exactly as we had wished, yet for men who have looked death in the face more than once the very consciousness that the war was over and that we had escaped falling into the hands of either the Italian partisans or the Soviet troops was cause enough for rejoicing.

Who of us could have thought that May, the month that sobs with thunderstorms and laughs with roses, would be for so many of us the last May in our lives?

As they pulled out of Italy the Cossack detachments of General Domanov lost all military discipline. There was no one to blame for this. There were no military encounters, except occasional exchanges of shots with partisans. The confusion resulted from the varied groups of men who from time to time joined General Domanov’s forces. First among these were the “reinforcements” which were constantly being sent to Domanov by the Germans who were anxious to rid themselves as painlessly as possible of “self -constituted” detachments. Then, at railroad junctions and elsewhere in the rear of the army, the numbers were increased by groups of former Soviet prisoners of war, made up of men who had gone over to the Germans right on the field of battle. But the factor that disrupted discipline the most was the unexpected appearance of a heterogeneous band of men from the Caucasus who wanted to join the “Domanov detachments.” Well armed with automatic rifles, clad in German uniforms, but speaking the “seventeen different dialects” of their country, they had gone through fire, flood, and hell at the time of the famous pacification after the Warsaw rising.

These accidents of circumstance were responsible for the undermining of authority in General Domanov’s best troops, the backbone of his detachments. The newcomers indulged in looting along the main highway, raped women, burned settlements. Their misconduct threw a shadow over those who behaved with strict military propriety, those who had come to fulfill a duty, to fight against communism, who believed also that the victory of the Western Allies would not be the end of the fight to save Russia.

In addition to these “self-constituted” detachments General Domanov was literally overrun with every kind of refugee—old people, women, children, families of émigrés, and those hapless forces (Ost-Arbeiter) who, hearing of the approach of Russian troops, overcame the most dreadful handicaps and trials to reach us.

When you add to these miscellaneous groups the families of the Domanov troops, you can possibly get a rough idea of the confusion in the army during the last days of the war in Northern Italy. I saw it in particular in Tolmezzo, a small town where the Cadet Engineers which I commanded were quartered.

With the news of Germany’s capitulation all of us moved into Upper Austria, to the town of Lienz. Our men were quartered in nearby Ober-Drauburg.

The move was accomplished with very little trouble. We were met and partially disarmed by the English division which had previously arrived there. General Domanov assigned me as aide-de-camp to General Vassiliev, who immediately sent me and a woman interpreter by the name of Rotova to staff headquarters of the English division.

The English general received us at once and very graciously. He listened attentively as the interpreter delivered the message from General Vassiliev: In the name of General Domanov and of all the detachments which had surrendered, General Vassiliev asked that we be considered English prisoners of war. He asked that the refugees be put under the protection of the English crown. As for the rest of us, the military, he asked no lenience, no indulgence, but merely pointed out that we were fully aware of our status as defeated soldiers and prisoners of war.

The Englishman smiled gently, nodding his graying head in a friendly way. When he had heard the whole message he asked the interpreter to convey his reply to the effect that the English were well able to appreciate and respect a defeated adversary and that they never harm their prisoners of war. The war is over. The victors and the vanquished must now “beat their swords into plowshares” and try as quickly as possible to establish a peaceful life. When he had finished, still smiling, he invited us to be his guests at lunch.

Not one of us, even for a second, had any doubt about the word of this English general. How could we do other than believe this royal officer of high rank? Joyfully and filled with high hopes we returned to Ober-Drauburg and passed the glad tidings on to both the military and the refugees.

They all heaved a sigh of relief. They felt that they were blessed with good fortune, because they knew the dire lot of their fellow countrymen who had been unable to escape from Soviet-occupied territory.

I recall bits of conversations between old émigrés and the more recent ones who had lived under the Soviet regime and were always on the alert for trouble. The older ones were fervent in assuring these newer ones, who felt that they had been betrayed by fate and by their fellow human beings, that there now lay before them, without any doubt, the prospect of a quiet life as ordinary citizens—well, yes, as émigrés, but in territory occupied by the army of the great and civilized British monarchy, bound by close ties to our former Russian dynasty.

I recall too the furtive, scarcely audible whispering that went on, to the effect that if anyone got into trouble it would, of course, not be the old émigrés, for in the twenty years of their wanderings they had acquired rights of citizenship in the free world.

Then there was the talk among the officers of the Domanov detachments. I remember the questioning eyes and the longing for reassurance of those who had come to us “from over beyond.” For them to be prisoners of the English, or rather the West, instead of the Nazis seemed equivalent to winning a lottery. How they cross-questioned the old émigrés as to what they might hope for!

How fortunate we are! they exclaimed. It could not possibly be bad to be prisoners of Anglo-Saxons. After all the English are gentlemen! We are not dealing with some ephemeral Hitler, said they, but with officers of His Majesty the King. An English officer does not give his word in his own right but on behalf of a sovereign power; even if he is a field marshal he speaks for the Crown.

How eagerly the rank and file drank in these misleading words! They never even noticed their high flown accents. They so longed to believe in the things they wished for. A peaceful life, quiet work, a family existence, property of their own....

In the early days of this “honorary captivity” it was possible to leave. Some did, those who distrusted the promises, others who learned that their families were somewhere nearby. A few unmarried men left, preferring to take no chances. But all these represented only a small percentage.

The rest sat and waited. Among them, as I have said, was our own “sensible” family, which believed in human justice and submitted to Gods laws. We were old Émigrés. So we undertook to train the newcomers—former Soviet citizens; former Soviet prisoners of war; former collective farmers and workingmen who first had been a German labor force (Ost-Arbeiter) and then soldiers and who were now straining to acquire their own individual personalities—we trained them all to become emigré, people perhaps without a national passport but still people.

The word “emigré” is a terrible one. It means a man without a country of his own. He is forever a burden, an undesirable element in the country that has taken him in. He may have all the brains in the world but to the legitimate children of any country he will remain the sale étranger, der verfluckte Ausländer. Yet to our former Soviet citizens the opportunity to become an émigrés seemed to be something ineffably wonderful. They looked into our eyes, they listened to every word, they literally drank in our stories about life before World War II. At first they were incredulous, but then they became convinced and dreamed of similar good fortune.

In these days, however, we were thankful to live quietly even if we were not too comfortable. There were no bombardments, no exploding mines, no raids by partisans.

We were quartered in different places, some in Ober-Drauburg, some in Lienz, some in the Peggetz camps spread along the highway. Since they did not feel that they were guilty of any wrongdoing, the domesticity of the Russians was soon in evidence. They laid out little vegetable gardens and settled down to keep house.

Days went by. People strayed in from other parts. Next door to us in Lienz there were some Serbian volunteers. We also met some Serbian Chetniks who were trying to get to some Italian city no one had ever heard of, Palma Nuova, where it seemed young King Peter II was waiting for them. We discovered too that not far away there were thousands of Cossacks in the Corps of General Helmuth von Pannwitz and a battalion from the “Varyag” regiment of Lublin. Then we got word of the tragic fate of parts of the ROA (the Vlasov forces).

This caused a pang in the hearts of some of us.

It was a strange life, this mixture of prisoners of war and refugees. We lived in comparative freedom, quartered in apartments, barracks, and haylofts. We realized that to feed so many people, and a great number of horses, was putting an unbearable burden on the Austrian population. Our conquerors paid scarcely any attention to us; they had not divided us into sheep and goats and seemed in no hurry to make any decision about us one way or another.

General Domanov made a number of “sallies” in the direction of the English. Accompanied by an interpreter, he made frequent visits to their headquarters and when he came out he appeared to be increasingly disturbed. To be more exact, each time he came out his face was gloomier and his step heavier. He seemed to shrink into himself, but he did not share his thoughts with anyone.

Why?

Did General Domanov have some secret knowledge? Was he already aware of the full extent of the amoral, criminal intentions of the Western Allies? Would it not have been better had he communicated these intentions to at least his senior officers, warning them of the dark clouds that were soon to cover the bright blue sky of our confidence?

Those days in May, 1945, pass before me now like a film in slow motion.

Every man is an egotist. Each of us in his own way was selfishly glad that he had escaped with his life and that he was able to save his family. That is the way I felt in Lienz.

We were all together there: my father, Nikolai, known as “Kolyun” to his family and his fellow officers in the Life Guards; Mother; Lili, my wife; Uncle Semyon; my grandfather, Peter Krasnov, and my grandmother, Lydia. We lived in different buildings, but we saw each other every day. Toward the end of the war we had succeeded in gathering the whole family together and that had seemed to me to be a good omen. I thought that this was to be the start of real family life for me with my dearly loved wife, my parents and grandparents, and other relatives. We would form a clan of Krasnovs perhaps; we would settle on the land or cross the ocean; but we would never be separated from one another again, and the young ones would see that the older ones lived out their lives in peace. Nevertheless there were moments when my optimism was rent by sudden gusts of premonition, feelings that told me it was not all over yet, that it was too soon to be building plans for the future.

Sometimes at night I would waken with a start and look at the dear features of my quietly sleeping wife. I somehow felt the need of impressing on my mind forever the way she smiled, the color of her eyes, her little habit of slightly raising one eyebrow, the timbre of her voice, the sound of her laugh. I took special pleasure in visiting my father. I would take his arm and walk up and down with him, discussing our situation, the various possibilities of what we should or should not do, speaking with him as man to man, soldier to soldier. I was full of childlike devotion to my mother, and I never missed a chance to spend some time with my grandfather or have a little joking word with my grandmother.

I thought then that I was trying...

Table of contents

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Prologue - From a Diary That Was Never Written

- 1 - Betrayal at Lienz

- 2 - Judenburg-In the Hands of Soviet Soldiers

- 3 - Lubyanka Prison-In the Hands of Soviet Police

- 4 - Separation in Lefortovo Military Prison

- 5 - Life and Death in Butyrki Prison-Prelude to the Labor Camps

- 6 - A Soviet Court and Krasnaya Presen Prison

- 7 - By Freight from Moscow to Mariinsk

- 8 - In a Siberian Camp

- 9 - Special Camps for Political Prisoners

- 10 - Last Days of the Special Camps

- 11 - Talks with Fellow Prisoners

- 12 - After Stalin Died

- 13 - At Large But Not Free

- 14 - In the Steppes of Central Asia

- 15 - The Way Back

- 16 - Hail and Farewell to Russia

- Epilogue

- Appendix