- 169 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The young American who became a living legend to the world tells how as a navy doctor he helped half a million Vietnamese refugees escape from communist terror…

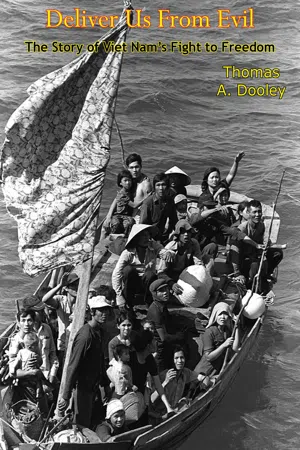

This is the true, first-hand narrative of a twenty-seven-year-old Navy Doctor who found himself suddenly ordered to Indo-China, just after the tragic fall of Dien Bien Phu. In a small international compound within the totally Communist-consumed North Viet Nam, he built huge refugee camps to care for the hundreds of thousands of escapees seeking passage to freedom. Through his own ingenuity and that of his shipmates, and with touching humor, he managed to feed, clothe, and treat these leftovers of an eight-year war. Dr. Dooley "processed" over 600,000 refugees down the river and out to sea on small craft, where they were transferred to U.S. Navy ships to be carried to the free areas of Saigon.

The "Bac Sy My," as they called the American doctor, explains how he conquered the barriers of custom, language and hate to become, as the President of Viet Nam said of him, "Beloved by a whole nation."

This is the true, first-hand narrative of a twenty-seven-year-old Navy Doctor who found himself suddenly ordered to Indo-China, just after the tragic fall of Dien Bien Phu. In a small international compound within the totally Communist-consumed North Viet Nam, he built huge refugee camps to care for the hundreds of thousands of escapees seeking passage to freedom. Through his own ingenuity and that of his shipmates, and with touching humor, he managed to feed, clothe, and treat these leftovers of an eight-year war. Dr. Dooley "processed" over 600,000 refugees down the river and out to sea on small craft, where they were transferred to U.S. Navy ships to be carried to the free areas of Saigon.

The "Bac Sy My," as they called the American doctor, explains how he conquered the barriers of custom, language and hate to become, as the President of Viet Nam said of him, "Beloved by a whole nation."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Deliver Us From Evil by Thomas A. Dooley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I—ENSIGN POTTS CHANGES HIS MIND

The Hickham Field airport terminal was jammed with military personnel and their dependents. November in Hawaii is lovely; when a light misty rain is falling, the Islands are enchanting. And I was going home. I was going home. Two weeks in Hawaii, winding up my two-year overseas stint, went fast and gave me two great moments. The second moment occurred right at Hickham Field.

The scene of my first was a U.S. Navy holy-of-holies—the Command Conference Room for Pacific Fleet Headquarters at Pearl Harbor. There I was to brief Admiral Felix B. Stump’s staff on my recent experiences in South east Asia. Admiral Stump was the Commander-in-Chief of the Military Forces of the Pacific. I was just a twenty-eight-year old Lieutenant (recently junior grade) in the Navy Medical Corps, in command of nothing whatsoever.

But I had had rich duty in the Orient. I had been stationed in the city of Haiphong, in North Viet Nam, Indochina and assisted in the epic “Passage to Freedom” that moved some 600,000 Vietnamese from the Communist North to the non-Communist South.

Indo-China had been a French colony. But on May 7, 1954, after eight years of bloody colonial and civil war, the key fortress of Dien Bien Phu had fallen to the Communists, and soon thereafter, at Geneva, the Red victory was nailed down in a peace treaty that arbitrarily split an ancient country in half. One of the treaty’s terms said if they wished, non-Communists in the north would be allowed to migrate to the south. Hundreds of thousands desperately wished to do so and most of those who made the trip traveled through Haiphong. And that was where I came in.

Needless to say, Admiral Stump’s staff had received regular reports on the operations at Haiphong, probably with frequent enough mentions of a young Irish-American doctor named Dooley. But evidently they wanted more, or at any rate Admiral Stump thought they did. So I was ordered to stop over on the way home to deliver a briefing, which is a lecture in uniform.

It was delivered in a room that collects stars. On this day, when I addressed some eighty officers for one hour, I counted sixteen of those stars on the collars in the front row. Captains filled the next few rows. Commanders brought up the rear.

Rank doesn’t scare me too much, but when it up on a man in this wholesale fashion it does shake him a little. But I told these men about the hordes of refugees from terror-ridden North-Viet Nam and how we “processed” them for evacuation. I told them how these pathetic crowds of men, women and children escaped from behind the Bamboo Curtain, which was just on the other side of Haiphong, and of those who tried to escape and failed. I told of the medical aid given them in great camps at Haiphong and of how, in due course, they were packed into small craft for a four-hour trip down the Red River, to be reloaded onto American ships for a journey of two days and three nights 1000 miles down the coast to the city of Saigon, in South Viet Nam.

I told them individual tales of horror that I had heard so many nights in candlelit tents, in the monsoon rains of that South China Sea area. I even got in some complaints. Why hadn’t certain missions been carried out more effectively? Why had American naval policy dictated such and such a course? So for one hour I talked. They all listened intently.

I suppose one measure of a lecturer’s hold on his audience is the length of time it takes for the questions that follow his speech. I must have had a pretty good hold because the questioning lasted more than seventy minutes. Finally three stars in the front row spoke up. “All right, Dr. Dooley,” he said. “You have given us a vivid picture and told us moving stories of courage and nobility. You have also raised a lot of objections. But you have not offered one solution or one suggestion on what we can or should do in the still-free parts of Southeast Asia.”

I responded, perhaps a bit unfairly, that two small stripes could hardly presume to offer solutions, if indeed there are any, to three big stars. My job was to take care of backaches and boils.

Then came my first big moment in Hawaii—the Walter Mitty dream moment that every junior officer has dreamed of since the Navy began. How often I had sat at table in the ship’s wardroom saying, “Well, if I were running this outfit....” Or “Why the devil didn’t the Admiral do it this way?” And now the Admiral was saying, “Well, Dooley, what would you do if you were wearing the stars?”

I took the plunge with a few suggestions, low level and not necessarily new.

“Sir,” I said, “I think that American officers ashore in Asia should always wear their uniforms. I think that American Aid goods should always be clearly marked. I think we should define democracy in Asia so that it will be clearer and more attractive than the definitions Asians get from the Communists.”

I said a lot more which, to be perfectly truthful, I can no longer remember, and even as I held forth I was worried about my cockiness. You get neither applause nor boos from such an audience, merely a curt “Thank you, Doctor.” The only punishment meted out to me when the show was over was a request to repeat the briefing to a lot of other audiences in Hawaii, military and civilian.

Only one man besides myself attended all my briefings. He was the hapless Ensign Potts, a spit-and-polish young officer five months out of Annapolis. He had been assigned to help me with the myriad little things I had to do on my lecture tour of Hawaii.

Ensign Potts, baffled me. He saluted me every time I turned around. Riding in a Navy car with me he would invariably sit in the front seat with the driver. When I would ask him to sit in the back with me his response would be: “No thank you, sir, I think it will be better if I sit up front.” Sometimes, after I had delivered a lecture in the evening, I would ask Potts to come to the beach with me for a swim. “No, sir, thank you,” he would say. “I had better go back to Officers’ Quarters.”

As we drove to Hickham Air Force base for my flight home, I again asked Potts to sit in the rear seat with me. “No thank you, sir,” he started to say, but by this time Ensign Potts was getting on my nerves.

“Mr. Potts,” I said, “get in this back seat. I want to talk to you. That is an order.”

Stiffly and reluctantly, he obeyed.

“Potts,” I said, “what the hell’s wrong with you—or with me? I think I get along with most people fairly well, but obviously you don’t like me. What’s up?”

“May I speak frankly, sir?” he asked.

“Hell yes,” I said.

“Then, sir,” he said, “allow me to say that I am fed up with you. I am fed up with your spouting off about a milling mass of humanity, about the orphans of a nation, a great sea of souls and all the rest of that junk. And what I am most fed up with, and damn mad about, is that most of the people you spout at seem to believe you.”

Ensign Potts stopped a moment to observe my reaction. When he saw I was listening, he continued:

“You talk of love, about how we must not fight Communist lust with hate, must not oppose tyrannical violence with more violence, nor Communist destruction with atomic war. You preach of love, understanding and helpfulness.

“That’s not the Navy’s job. We’ve got military responsibilities in this cockeyed world. We’ve got to perform our duties sternly and without sentiment. That’s what we’ve been trained for.

“I don’t believe your prescription will work. I believe that the only answer is preventive war.”

Evidently he had thought a lot about it. He explained that some 200 targets in Red Russia, Red China and the satellite nations could be bombed simultaneously and that this would destroy the potential of Communism’s production for war. Then a few more weeks of all-out war would destroy Communist forces already in existence.

Sure, the toll of American lives would be heavy, but the sacrifice would be justified to rid mankind of the Communist peril before it grew strong enough to lick us. For that matter, maybe it was too late already.

Slowly Dooley was beginning to understand Potts. The Ensign had nothing against me personally; he just didn’t like what I was preaching. He himself had a radically different set of ideas, and many Americans, I suppose, share his views. I do not.

The Ensign had not yet said his full say. “Dr. Dooley,” he concluded, “the oldest picture known to modern man, one of the oldest pieces of art in the world, is on the walls of a cave in France. It shows men with bows and arrows engaged in man’s customary pastime of killing his fellow man. And this will go on forever. Prayers are for old women. They have no power.”

With this he fell silent, sucked in a deep breath and slumped in his seat. He had vented his hostility and was appeased.

Just then I noticed that our car was not moving. We had arrived at the terminal, but the sailor chauffering the car was too engrossed in our conversation to interrupt. Potts and I stepped out, disagreeing but friends at last.

And that brings me to the second of my two big moments in Hawaii.

I stood in the misty perfumed rain at the terminal. I was heading home. Things would be quiet now. They would be pleasant and uneventful. I was going to sleep, eat, and then eat and sleep again. There would be no turmoil. No hatred. No sorrow. No atrocities. No straining with foreign languages (I can speak Vietnamese and French, but they take a toll on the nervous system).

The terminal building at Hickham is immense. Preoccupied with thoughts of going home, I did not hear the first shout, but the second one came through loud and clearly. From the other end of the waiting-room, someone was yelling: “Chao Ong Bac Sy My,” which in Vietnamese means, “Hi, American doctor.”

I turned around and was enmeshed in a pair of strong young arms that pinioned my own arms to my side. A Vietnamese Air Force cadet was hugging me tight and blubbering all over my coat. He was a short, handsome lad of perhaps sixteen. Squeezing the breath out of my chest, he was talking so fast that it was difficult to understand what he said. Suddenly there were about two dozen other olive-skinned youngsters in cadet uniforms swarming around me, shaking my hands and pounding me on the back as an air-hammer pounds a pavement. They were all wearing the uniform of the Vietnamese Air Force. And everyone concerned was bawling all over the place.

“Don’t you remember me, American Doctor? Don’t you remember?” asked the boy who still had me pinioned in his bear-hug.

“Of course I do,” I lied—who could remember one face among those hundreds of thousands?—but behold! the lie turned into truth and the old familiar gloom came over me. The boy had no left ear. Where it should have been, there was only an ugly scar. I had made that scar. I had amputated that ear. I might not remember this particular boy, but I would never forget the many boys and girls of whom he had been one. The ear amputation was their hideous trademark.

“You’re from Bao Lac,” I said, disentangling myself from his embrace. Pointing to others in the group, I added, “And so are you, and you and you.”

Each of them also had a big scar where an ear should have been. I remembered that in the Roman Catholic province of Bao Lac, near the frontier of China, the Communist Viet Minh often would tear an ear partially off with a pincer like a pair of pliers and leave the ear dangling. That was one penalty for the crime of listening to evil words. The evil words were the words of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Father, Who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name....Give us this day our daily bread....and deliver us from evil....” How downright treasonable, to ask God for bread instead of applying to the proper Communist authorities! How criminal to imply that the new People’s Republic was an evil from which one needed deliverance! A mutilated ear would remind such scoundrels of the necessity for re-education.

The boy spoke of his escape from North Viet Nam in November of 1954, when he had come to my camp. There I had amputated the stump of his ear, dissected the skin surfaces of the external canal, then pulled the skin of the scalp and that of the face together and sutured them. The tension was great on the suture line, and I knew the scar would be wide and ugly. But, with the limited time and equipment available, I had no alternative. Would he hear again from that ear? Never. Only from the other ear would he ever hear words, evil or holy.

All of the Vietnamese youngsters now in the Hawaiian terminal had passed through our camps at Haiphong, and many of them bore this trademark. I had put them on small French craft or on sampans which carried them to American ships to be taken to Saigon. There those who had reached the age of sixteen were old enough to join the newly created Air Force of Viet Nam. At sixteen they were men, preparing to regain the north half of their country from the Communists.

Under an American Military Aid Program, this contingent was going to Texas to be trained as mechanics. At the airport in Hawaii they had spotted the American doctor who had helped them a year earlier. They remembered him. I remembered only the scars.

A fairly large crowd, mostly Americans, had been attracted by our noisy and tearful reunion. Some people wanted to know w...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- CHAPTER I-ENSIGN POTTS CHANGES HIS MIND

- CHAPTER II-THIRTY-SIX BRANDS OF SOAP

- CHAPTER III-NEW CARGO FOR THE U.S.S. MONTAGUE

- CHAPTER IV-THE REFUGEES COME ABOARD

- CHAPTER V-DR. AMBERSON’S TEAM

- CHAPTER VI-THE CITY OF HAIPHONG

- CHAPTER VII-HOW DID IT ALL COME ABOUT?

- CHAPTER VIII-CAMP DE LA PAGODE

- CHAPTER IX-OUR “TASK FORGE” SHRINKS

- CHAPTER X-THE POWER OF PROPAGANDA

- CHAPTER XI-THE STORY OF CUA LO VILLAGE

- CHAPTER XII-PHAT DIEM’S LONGEST HOLY DAY

- CHAPTER XIII-BUI CHU MEANS VALIANT

- CHAPTER XIV-THE ORPHANAGE OF MADAME NGAI

- CHAPTER XV-COMMUNIST RE-EDUCATION

- CHAPTER XVI-LEADING THE LIFE OF DOOLEY

- CHAPTER XVII-THE DYING CITY

- CHAPTER XVIII-AFTERWORD

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER