- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

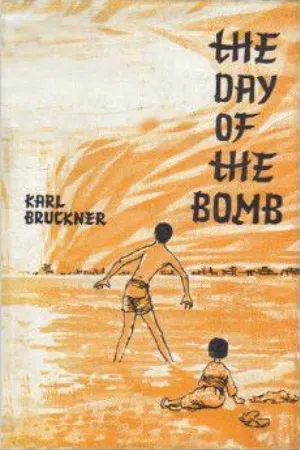

The Day of The Bomb

About this book

First published in 1961 under the German title Sadako Will Leben (meaning Sadako Wants to Live), this non-fiction book by renowned Austrian children's writer Karl Bruckner is considered his most famous work.

Telling the vivid story about a Japanese girl named Sadako Sasaki, who lived in Hiroshima and died of illnesses caused by radiation exposure following the horrific atomic bombing of the city in August 1945, the book has been translated into most major languages and has been used as material for peace education in schools around the world.

Telling the vivid story about a Japanese girl named Sadako Sasaki, who lived in Hiroshima and died of illnesses caused by radiation exposure following the horrific atomic bombing of the city in August 1945, the book has been translated into most major languages and has been used as material for peace education in schools around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Day of The Bomb by Karl Bruckner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

ON the morning of July 20th, 1945, the following events took place.

From the air above the shimmering Inland Sea came a faint droning. A Japanese observer on the coast of the island of Shikoku signalled to Defence Headquarters for Southern Japan, stationed at the ancient castle in Hiroshima: “Enemy bomber approaching.”

Some minutes later a second signal followed it. “Enemy bomber identified as reconnaissance plane.”

Defence Headquarters sounded no air raid warning for the town, so as not to interrupt work in the armament factories unnecessarily. Enemy planes had flown over Hiroshima several times lately without dropping bombs.

* * * * *

On the banks of one of the six branches of the River Ota, the crippled boat-builder, Kenji Nishioka, was fishing, seated on a stone projecting from the muddy bank. Kenji let the water ripple round his naked feet. Its coolness eased the burning in his swollen ankles. Last night the pain had been worse than ever. He looked thoughtfully at his ailing limbs. Was it the heat of summer that made his ankles swell? Or was it, as the old woman who lived next door to him maintained, that all evils were due to the war? There might be something in what old Kumakichi said. It was certainly due to the war that for the past few months he, Kenji, had only been getting as much rice every third day as he had formerly eaten in one. The local government officials probably thought of all old people as useless mouths, because they gave them so very little food. Younger people didn’t respect their elders anymore. Yes, indeed, war corrupted morals. If it didn’t end soon, old people would starve.

Gloomily Kenji hauled in his line and stuck a fresh bait on his hook. He had been sitting here since early morning without a nibble. If he had still owned his good boat he could have gone out on the water to fish. But this boat had been commandeered for the Navy in the very first year of the war. So had all the ship’s timber that he had accumulated in the course of the years when he was still building heavy fishing smacks as well as light pleasure craft.

From some indefinable direction came a droning. The noise increased, faded, and increased again.

Kenji Nishioka looked skywards, blinking. The sun dazzled him. The slit eyes in his round full moon of a face now looked mere streaks painted in with Indian ink. He attempted to discover the source of the noise. Now he tilted his head so far back that his flat straw hat slid off his bald head and fell in the mud. This hat had formerly served as headgear to a rickshaw coolie, who, on being called up, had left it with his creditor, Nishioka, as a pledge for some small loan. At that time the hat had been nearly new. Now it was tattered and shapeless. All the same, it was Kenji’s favourite headgear, and he therefore carefully wiped off the mud which clung to it. He was so busily engaged in doing this that he forgot what he had previously been looking for in the sky. As an approaching drone reminded him of it again, the noise was drowned by the sudden pounding of one of the many guns from the Mitsubishi shipyard on the opposite bank. A dirty grey puff of smoke shot up into the air. Kenji Nishioka ceased to worry about the droning in the sky.

* * * * *

Along the embankment marched a company of soldiers, singing. Only one, the last on the left, raised his eyes heavenwards. He saw an aeroplane high over the water. To him it looked a mere speck. “An enemy bomber,” said the soldier to his neighbour, gesturing furtively in the appropriate direction. His comrade gave the aeroplane a fleeting glance. Then he whistled through his teeth to show how remote he reckoned the danger to be.

The young officer leading the company to the barracks square turned round unexpectedly. Sternly he ran his eyes over the ranks of the soldiers. None of them, as far as he could see, was looking in the direction of the bomber. That was a good thing. A soldier should despise danger. Even that old man down there on the river bank was peacefully wiping his hat clean rather than honouring the bomber in the sky with any attention. The old man was setting a good example.

* * * * *

By the side of the road, ten-year-old Shigeo Sasaki tried to keep step with the marching soldiers. This was not easy, for Shigeo was walking on stilts. Two feet above ground-level, he was balancing himself on foot-rests screwed into poles taller than a man’s height. Shigeo too heard the drone of an engine in the sky, but he did not spare the time to look up. He was more interested in trying to impress the soldiers. Behind him trotted his four-year-old sister, Sadako. She was crying because she could not keep up with her big brother. At last the chubby-faced child stood still and began to scream shrilly, stamping her feet on the ground. Her tiny, high-heeled wooden clogs rattled on the pavement like a burst of kettledrums. She held out her arms in front of her as if she would have liked to pull Shigeo off his stilts. The latter plodded calmly on, smiling at the soldiers in the hope of attracting admiration, until he stumbled and had to jump down. Some of the soldiers grinned then, amused. Shigeo pretended that he had only jumped down for his sister’s sake, and he ran back. Putting his arms round the little girl, he lifted her up and spun round with her in a circle, to pacify her. But she was not to be consoled. Shigeo grew angry. He pointed to the aeroplane in the sky. “Do you see that big bumble-bee up there? It will come right down and sting you if you are not quiet.”

The child squinted upwards, grew quiet and stuck her finger in her mouth. To her, the aeroplane high up there really did seem a spiteful bumble-bee.

* * * * *

For the third and last time Kenji Nishioka, the boat-builder, tried to see the aeroplane in the blue sky. Now he had found it. It was just hovering over the centre of the town. Kenji thought: “If that airman is one of the enemy he must be a brave man. He has flown to us across the great ocean.” He changed the bait on his hook and shook his head reflectively. Then he went on to think: “It is an enemy. Our planes don’t make so much noise. It is probably a reconnaissance plane. Otherwise the air raid warning would have sounded.” He felt a twitch at his line and drew it in, but the fish had not bitten. Kenji continued to reflect. “Even so, I wouldn’t have run to the air raid shelter. I’ve never done anyone any harm, so why should a stranger want to kill me?”

* * * * *

The pilot of the plane was Captain Lawrence A. Kennan. He had made many successful reconnaissance flights and had been decorated more than once. Before the war he had been Managing Director of a firm in Detroit that dealt with the construction of steel-and-concrete bridges. He had loved his job. Building bridges seemed to him a way of bringing people closer to one another. His business trips had taken him to South America, to Australia, and even to India and the Philippines. In those days the world had seemed to him an unimaginable miracle at which he marvelled whenever he had a moment to do so. The war, however, seldom left him time enough to marvel at the beauties of nature. Except for two short periods of leave, he had been on active service uninterruptedly ever since the conclusion of his observer’s training course, constantly threatened by enemy planes and by anti-aircraft defences from the ground. Even on the picturesque tropical islands over which he had flown, death was always lurking. This flight over the Japanese islands was his twelfth in eighteen days. At early dawn he had set out with a crew of six from the Pacific island of Tinian in the Marianas. It was a flight of more than 2,500 miles there and back. Now he was circling five thousand feet above his objective—Hiroshima. He knew that the observer in the tail of the plane was now photographing the town.

Captain Kennan permitted himself a downward glance. He saw the delta of the River Ota and the six islands on which Hiroshima was built. The view of the city impressed him greatly. A holiday in Japan in time of peace would be a marvellous experience, he thought. He would bring Liddy, his wife, and Evelyn and Bud, the children, and with them he would visit all the cities over which he had made reconnaissance flights during the war. When would this war be over? Would it go on for months still? Or for years?

Years?

Impossible. The enemy’s might in the Pacific had been destroyed. The Japanese had been forced to abandon all the regions they had occupied; they had lost their Navy and had withdrawn to their island realm. There, it is true, they were still formidable opponents. A sea invasion could be carried out only at cost of appalling losses. It was better not to think of such slaughter. He must not think of it! Otherwise he would see those dead bodies once more, those seas of flame, that hell! No. He must blot out all thought.

Too late.

He was in its grip already.

The muscles in Kennan’s jaw stiffened, his hands clenched. He writhed as if in pain.

During the course of the war he had seen so much meaningless destruction, lived through so many ghastly atrocities that on certain nights, tormented by horrible dreams, he would cry out, awaken, and rush out into the night still filled with horror. When he finally came to himself, either because he stumbled, ran into some obstacle or was shouted at by a sentry, he always felt what he had gone through in the war must have been a dream too. He was certainly no longer the healthy, cheerful Lawrence A. Kennan who had enthusiastically enrolled as a pilot at the beginning of the war. He was suffering from a strange disease. Several times, during flights in the past weeks, whenever he thought of the events of the war, he had been seized with an overwhelming hatred for his plane. At such times he would clutch the control column in a wild grasp, strain at his safety belt and experience a violent longing to tear everything to bits, to destroy everything. When he had once overcome such a fit, which lasted only a few seconds, he would feel as exhausted as if he had just run a gruelling race. After each attack he had resolved to talk to the medical officer about it, but he never carried out his intention. He did not want his comrades to think him a cowardly hypocrite or a shirker. To his mind, each one had to bear his own share of suffering in this war—bear it to the end, whether sweet or bitter.

The co-pilot was called George Hawkins. He was highly popular with the squadron on account of his talents as an actor. He came from Boston, where he had been a crane-driver in the docks. All his life this fair-haired lad of twenty-eight with the baby-blue eyes had dreamed of becoming a famous actor. Owing, however, to a slight vocal defect—his voice was too hoarse—the way to the footlights had been barred to him. An astonishing memory enabled him to recite major rôles from memory. Shakespeare was his favourite playwright. Throughout every flight Hawkins’s thoughts were busy with Shakespearian heroes, and sometimes he was Othello, sometimes King Lear, sometimes Hamlet or Caesar. Meanwhile, as reliably as a machine, he fulfilled his duties as co-pilot, watched the instruments attentively and kept up communications without ever forgetting the point at which he had been interrupted in his rôle. If the plane were shot down, he would probably declaim a speech from one of Shakespeare’s tragedies while still hanging from his parachute.

William Sharp, the curly-headed observer, was working the built-in camera with all the assurance of a skilled professional. Before the war, despite his youth, he had been reckoned an expert in the production of optical glass. In the Pittsburgh factory in which he had been employed, he had earned a lot of dollars, but the money had always slipped through his fingers. He loved gambling, was passionately fond of poker, and loathed all forms of compulsion. As an airman, he was obliged to conform to countless regulations, and he therefore also hated any superior who prevented him from ignoring these regulations. He cared for his adored camera, however, with the zeal of a lover. What he photographed was a matter of indifference to him. Tropical landscapes, islands, cities or mountains were of no interest to him. He merely knew that he was now flying over a Japanese port called Hiroshima. For all he cared, it might just as well have been called Honolulu or Singapore. Now that he had finished his task, he occupied himself in planning how to persuade his companions to play poker with him that evening in camp on the island of Tinian. At the moment he had a great longing for a cigarette. He licked his lips voluptuously and glanced at Sam Miller, the air mechanic. That stiff old stick was a Regular—he had served in the Air Force even before the war. Taciturn, surly fellow that he was, he would shop his own brother if he caught him smoking on duty.

As substitute for a cigarette Sharp pulled out a piece of chewing gum from his pocket and bit grimly into the sticky mass. To pass the time, he gazed through the viewer and watched the town gliding away beneath him. The sea appeared. The flight back to Tinian had begun. He was glad of that. The chances of playing a game of poker grew better every minute. It was to be hoped that no enemy aircraft would imperil this chance. The Japanese were fanatically reckless. It was incredible that they hadn’t harassed this reconnaissance plane. Perhaps it hadn’t seemed worth the trouble to them. Perhaps it hadn’t seemed worthwhile to bother about a single plane. If only they had known why this handsome, four-engined machine had been circling over the town they would have strained every nerve to bring it down. Today’s photographs of Hiroshima were certainly wanted for a definite purpose. Something quite out of the ordinary seemed to be brewing in Tinian. For the last two days Staff Command had been hectically active. Special courier planes flew back and forth. The senior officers whispered to one another. If that didn’t mean that something out of the ordinary was hatching, Observer William Sharp would eat his parachute on the spot.

O’Hagerty, the air-gunner, scanned the horizon with the keenest attention. He had switched off his tho...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE

- PART TWO

- IN-MEMORIAM

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER