![]()

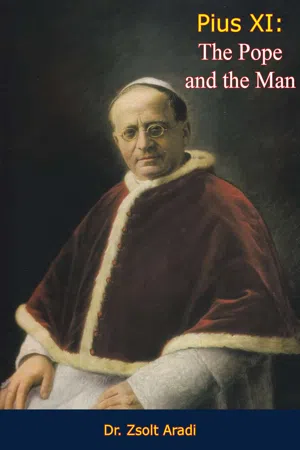

PIUS XI — THE POPE AND THE MAN

CHAPTER ONE — Younger Days in the Brianza

ACHILLE RATTI was as much a product of Northern Italy, more specifically of Lombardy, as Erasmus of Rotterdam was a product of Holland. There were few greater humanists than Erasmus, who lived in an age of controversy, yet he was able to keep his identity not only during his lifetime but through the centuries that followed. Erasmus had a global view of international affairs; he never became a narrow-minded nationalist; he had understanding for the views of violently opposing parties of different nations. But he had deep roots. He was Erasmus of Rotterdam, so Flemish that the prototype of the quiet, sometimes cool, well-mannered Dutchman could be carved out from his figure. His attachment to his roots did no harm; on the contrary, it broadened his universality and his thinking.

So with Achille Ratti. He cannot be understood unless we know the native soil from which he sprang: the environs of Milan. His roots were so deep and his attachment to Milan so great that in an earlier age he would have been called Achille of Milan, and known as such through the ages.

Desio, where Achille Ratti was born on May 31, 1857, is a village in the lowlands of Lombardy in the north-western tip of Italy, dominated by the massive and majestic Alps. The village whose history goes back to Roman times—historical documents indicate that Desio was an important Christian center in the sixth century—forms the center of the larger Brianza region, and sits on the main road between the famous St. Gotthard Pass and the great industrial city of Milan only fifteen miles away.

Despite its closeness to Milan, where the industrial revolution and the social and political transformations of the nineteenth century found their most advanced expression in Italy, the Brianza region, of which Desio is the most important community, managed to keep relatively immune from these swift and bewildering changes.

The silk and textile plants that dot this area did little to modify the traditional landscape or the character and folkways of the people. The inhabitants of the plains of Brianza live in a close, vital relationship with the mountains, whose snow-capped peaks they can see on clear days, and with its dark, mysterious valleys and swift torrents that eventually find their way to the River Po.

Up to the beginning of the twentieth century most inhabitants of the area still worked as agricultural day laborers on the vast estates of the local gentry, and the region still preserved its reputation as the home of Italy’s finest carpenters and cabinet-makers.

The family of the future Pope, the Rattis, belonged to the relatively newly created lower industrial middle class. Before the industrialization of the area around Milan they had been artisans and peasants.

At the time that Achille Ratti was elected Pope—in 1922—the inevitable attempt was made to link the Ratti family to the great aristocratic families of the region, an attempt that naturally was unsuccessful and which in no wise was encouraged by the Pope, amused over the pretentiousness of the project.

The family of Achille Ratti, however, can be traced in documents that go as far back as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Rogeno, upper Brianza, in the vicinity of Lake Como. Most of his antecedents were peasants, as was the progenitor of the Ratti family, a certain Gerolamo.

Later, the family occupation shifted from the soil to the workshop. Members of the Ratti clan became skilled lathe operators, specializing in wood and later in metal, and toward the end of the nineteenth century some of them worked as metal lathe operators for the state railway. Other relatives became spinners and weavers in the silk mills, but they stubbornly held on to small properties and farms.

In a word, the Rattis were a hard-working, simple, industrious folk. By Italian standards, however, they were relatively well-to-do, as is indicated by the generous gifts they made for charitable purposes or for the embellishment of local churches and monasteries registered in the church annals of Rogeno and Massiola.

In the birth certificate of Achille Ratti, his father is listed as a landowner. The elder Ratti did own some land, but he also worked as a weaver in the small silk factory in Desio owned by the Count di Pusiano and his brothers. Later, he became its manager.

The house in which Achille Ratti was born is a three-story building on Via Lampugnani (now Via Pio XI){1} with a center section. Two wings of the house are connected at the end of the courtyard by a covered bridge. The house did not belong to the Rattis, but to the Pusiano family. In fact, the “factory” was located on the same premises and the hum and din of the spinning and weaving machines were familiar sounds to the Ratti children as they romped and played about the big house.

Achille Ratti was the fourth child of Francesco and Teresa Ratti. His mother, née Galli, came from the neighboring township of Saronno, and she had already presented Francesco with three boys: Carlo, Fermo and Eduardo. A girl, Camilla, was born in 1860.

Signora Ratti was a dark-haired, medium-sized woman, with lively dark eyes. There was no question about the fact that she ruled the Ratti roost, In a sentimental poem written by her son Achille on the occasion of her birthday in 1882, the spankings received by the children are humorously remembered, and Achille himself was no exception, even though she treated him with special care because he was the youngest son.

On June 1, 1857, the day after his birth, the Rattis took their fourth-born son to the nearby cathedral in Desio, where he was baptized as Ambrosio Damien Achille. The boy was named in honor of an early Christian martyr whose name is still venerated on the Via Appia in Rome in the little church of St. Nereus and Achilles. According to the Desio parish records, Ambrosio Ratti of Rogeno, from which the family originally came, was godfather to the child, and Luigia Zappa of Desio, a friend of Signora Ratti, his godmother.

Teresa Ratti, who had married Francesco in 1850 when she was twenty, had all the traditional virtues of the Italian women of her time. From the moment of her marriage she dedicated herself completely to the welfare of her husband and the growing family, despite her delicate health and constitution. Signora Ratti frequently suffered from headaches, so much so that her son, who never had a serious illness until his seventy-ninth year, remarked that her pains and sufferings must have included the share that should have been his.

The Rattis lived an orderly, well-regulated life. Francesco left the house early each day to supervise the work at the factory, or to see business associates, very often in Milan, to arrange for sales and purchases of silk products. Milan at that time was a booming business center; the grain and wine markets were jammed with people and humming with activity. But whenever he stayed at home in Desio, Signora Ratti made it a point that the family should take its meals together.

The house of the Rattis in Desio was well furnished, in a style typical of the lower bourgeoisie of the nineteenth century. Many of the objects and furnishings in the house had great sentimental value for Achille Ratti. Among other things, for example, he kept a music box from the paternal home in his room until the end of his life.

Since the family was neither poor nor wealthy, Francesco Ratti was able to maintain the traditional independence of his forebears. Although he was an employee, this was possible because he owned enough land and had enough savings. Hard work and constant activity were the basis of the family’s well-being. This was a lesson that was not lost on Achille Ratti who later, as Pope, once asserted that “La vita è azione” “Life is action.”

Francesco Ratti allowed himself no luxuries. The education of his five children was for him a primary goal and he was determined to make any sacrifice in order to put the children through the higher schools. And his wife never failed in her thrift and was as alert in running the household as her husband was in conducting his business.

Young Achille was very much influenced by his mother and much devoted to her. Although Achille was a normal, active and very good-humored child, he was still the most serious of the five, and prone to solitude and meditation. It was for this reason that his schoolmates called him “the little old man.” Otherwise, Achille was just like any of the other boys in the village, sharing their games, pranks and experiences. In church he often served as an altar boy, and even learned how to ring the church bells. The bells of Lombardian churches have a tonality peculiar to them. Young Achille was so fond of the sound of the bells, when one church seemed to respond to the other in a harmonious obligato that faded into the distance, that when he became Pope a recording was made of the bells of Desio and presented to him as a gift. He kept this recording until the end of his life, playing it often whenever nostalgia for his old hometown came over him.

Achille’s first teacher was a simple country priest named Don Giuseppe Volontieri. He was a truly remarkable man, who had a deep influence on the pupils who were entrusted to him. At that time there was no religious instruction in the schools, and Don Giuseppe, as he was called, taught the children of Desio, ranging in age from six to ten, the elements of religion in his own home.

In addition, it was his custom to discuss the daily problems of life that arose in the village with his “class,” especially during the frequent trips to the surrounding countryside where he would patiently and lovingly point out to them the wonders and beauties of nature. In explaining the events that impinged at some point or other on the lives of his young charges, whether it was a trivial family dispute or the behavior of the soldiery, Don Giuseppe never tried to varnish reality. Yet he always discussed such matters in the context of his own deep faith and natural goodness in a way that, instead of dismaying the youngsters, actually strengthened their belief in the essential goodness of life and man and the inscrutable ways of God. He would often counsel his young audience, among whom Achille was an avid listener, to live according to the principle of Ignatius Loyola: “Pray as much and as deeply as if everything depended on God. Work as hard and as strenuously to achieve whatever spiritual or other aim you have, as if everything depended on you.”

Through his pupils Don Giuseppe was always sending gifts of food and money to the poor of the village. And his pupils’ parents were often the surprised recipients of large bouquets of flowers gathered for them at his tactful suggestion. Don Giuseppe taught for forty-three years in the village of Desio and, in a sense, exerted a greater influence on the townspeople than did the political events that were also shaping their lives, or the other priests attached to the local parish. As late as 1956 there were still old residents in Desio who remembered his name because their fathers and grandfathers had so often extolled his lofty qualities as a man and as a priest.

When Don Giuseppe died, in 1884, & was Achille Ratti who delivered the funeral oration and who wrote the still legible inscription on his tombstone in the cemetery of Desio: “Giuseppe Volontieri was full of enthusiasm for the honor of the Church and school, and educated children to love both.”

The climate of Desio is much like that of Milan. Winter can be very cold, autumn is always beautiful, but the summer is dreadfully hot and humid, unrelieved by refreshing breezes or showers. Between noon and four o’clock in the afternoon the hot streets, otherwise so bustling with life, are deserted and the shutters on the houses are drawn tight.

But life in Desio was not exactly idyllic. It was the time when the unity of Italy was being forged. Achille Ratti was born in the days of the Risorgimento and his growing intellect and imagination, from the earliest days of his life, had been crammed with the images and rhetoric of this romantic era influenced by European liberalism and nationalism.

The earliest event that Achille Ratti remembered was also one of the great historical events in Italian and European history. He recalled that one day in 1859, when he was only two years old, his father rushed into the house breathlessly, shouting: “The Germans are at Desenzano!” This was at the time of the Franco-Italian war against the Austrians, as a result of which the Hapsburgs were driven out of Lombardy and Venice. This event set off a chain reaction that ultimately ended with the occupation of Rome by the forces of the revolution and completed the unification of Italy.

Achille Ratti remained ever aware of the “two” Italies within the unified country. He knew that northern Italy is different from the rest of the peninsula, clearly distinguishing between Italy north of the Po and south of the Po. In his opinion, people north of the Po were more enterprising. This was why, as Pope, he never would send help if a routine request came from north of the Po. He would explain that “People there should help each other because they are able to do so.” To be sure, he loved the Brianza people and they in turn loved him. Like any other Italian, Achille Ratti also kept strong ties with his native region.

As a child, Achille Ratti spoke two languages: Italian and the meneghino dialect used in the family and among his playmates. In his later years he loved to use the dialect with his intimates, particularly when talking about matters Milanese, so that he could give full scope to the colloquialisms reminiscent of his beloved Milan and Brianza. He spoke the meneghino dialect well, with the correct tonality and expression, a skill which put him in good company. Among this company were Manzoni, the great Italian novelist of the nineteenth century, Antonio Stoppani, one of the teachers of the future Pope, who was also a famous geologist and author of Bel Paese, and Msgr. Ceriani, Ratti’s predecessor at the Ambrosiana in Milan. All three men wrote poetry in the meneghino vernacular. Achille Ratti followed their example. One of his poems in dialect, containing forty-three stanzas, was dedicated to his mother as a birthday tribute on October 15, 1882.

Achille Ratti’s love for the Brianza ever remained a strong emotional factor in his life, a concrete and perennial proof of how deep were his roots in the soil, the spirit and the history of this region and its people. In 1922, for example, when the Brianza region showed itself to be less than enthusiastic toward fascism in the elections, the fascists were enraged. In revenge, the Blackshirts destroyed the locals of the Partito Popolare (People’s Party), offices of Catholic Action and parish halls. The fascists held these three groups responsible for their defeat. In a letter to his Secretary of State, Cardinal Gasparri, Pius XI strongly deplored the violence and vandalism, particularly that against the parish halls, and he immediately gave half a million lire for the relief of the victims and reconstruction of the damaged properties. It was at this time that he earned the sobriquet, “Il Papa Brianzolo,” the Pope of Brianza.

In addition to his family and his teacher, Don Giuseppe, two other men exercised particularly great influence on the boy Achille: his uncle, Don Damiano Ratti, and Archbishop Calabiana of Milan. Achille spent his summer vacations with this uncle whom he loved. Don Damiano was the same kind of priest as Don Giuseppe: devout and full of a sense of humor. Moreover, he was a pastor with a broad knowledge of the world. He loved youth and knew how to kindle its idealism and imagination.

Don Damiano was well liked by his fellow priests and by his superiors, too. One of his great friends was Archbishop Calabiana, who would often come to spend several days in the delightful atmosphere of Don Damiano’s house. It was here that the young Achille frequently met older seminarists who took him on walks, and where he also met the Archbishop. This particular meeting was one of the most important, if not decisive, regarding his future.

During the summer season Don Damiano’s house was the gathering place of young students and seminarians, a veritable youth hostel. Archbishop Calabiana liked and encouraged this atmosphere charged with youthful spirit and energies, above all because the young guests shared his ideas of Italian patriotism.

Archbishop Calabiana was no ordinary figure in the fights for Italian unity. Born in 1808, he had become Bishop of Casale at thirty-nine. A member of the Piedmontese aristocracy, he had been given an important post in the court of King Carlo Alberto, with the title of royal almoner. Calabiana was a man of impeccable conduct, an exemplary priest, and a defender of the rights of the Church. But at the same time he was an unswerving supporter...