eBook - ePub

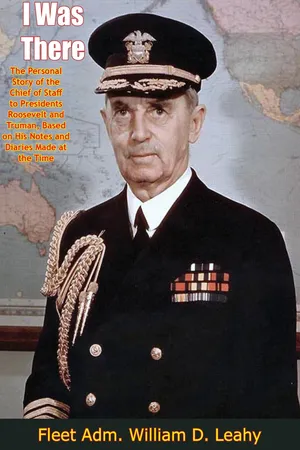

I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman

Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time

- 548 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman

Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time

About this book

Admiral Leahy, as Chief of Staff to both wartime presidents, was the senior-ranking military man in the United States. He is, therefore, the only living American who could have written this highly comprehensive and significant book. I WAS THERE is one of the most important chronicles of our time. A frank appraisal of great men and stirring events, it is a forthright and intensely interesting narration of the curial war years.

"I was there. Throughout almost five years from November, 1940, to the end of World War II in September, 1945, my duties placed me at pivotal points in the high command that accomplished the defeat of our enemies against what at times seemed heavy odds. These observations are based on participation in many historic discussions at which the course of the war was charted and at which attempts were made to map the road to peace."—Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chapter I

"I was there. Throughout almost five years from November, 1940, to the end of World War II in September, 1945, my duties placed me at pivotal points in the high command that accomplished the defeat of our enemies against what at times seemed heavy odds. These observations are based on participation in many historic discussions at which the course of the war was charted and at which attempts were made to map the road to peace."—Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chapter I

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman by Fleet Adm. William D. Leahy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1—I WAS THERE

I was there. Throughout almost five years from November, 1940, to the end of World War II in September, 1945, my duties placed me at pivotal points in the high command that accomplished the defeat of our enemies against what at times seemed heavy odds. These observations are based on participation in many historic discussions at which the course of the war was charted and at which attempts were made to map the road to peace. These discussions include:

Washington, May, 1943—which was the fourth of the nine Allied war councils. At this meeting and others later Winston Churchill appeared to some of us to carry his insistent campaign to preserve the British Empire to a point where it might not be in full agreement with the President’s fundamental policy to defeat Hitler as quickly as possible.

Quebec, three months later—where global strategy was hammered out and the British came to an agreement with us in important decisions regarding the American intention to invade Europe by way of the British Channel.

Cairo, November and December, 1943—here the Allies made a bargain with Chiang Kai-shek which they did not keep, and the Turks would not bargain at all. Here also our persistent British friends strove mightily to create diversions in the Mediterranean area, which the American command did not consider worth taking precedence over the agreed plan for striking at Hitler close at home with a cross-Channel assault.

Teheran, between the Cairo sessions—when President Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met together for the first time. With their military and political staffs they mapped the defeat of Germany. They also had their first arguments on post-war settlements, including the Polish border question which later was to be an example of the ruthlessness of our Soviet ally.

Quebec again, in September, 1944—here the coming Battle of Japan was at the top of the agenda. Nothing had happened to alter my conviction that the United States could bring about the surrender of Japan without a costly invasion of the home islands of the enemy, although the Army believed such an offensive necessary to insure victory.

Momentous Yalta, February, 1945—when we discussed with Russia participation in the war on Japan, which was, in my opinion, an unnecessary move, but in which Roosevelt joined in the belief that Soviet participation in the Far East operation would insure Russia’s sincere co-operation in his dream of a united, peaceful world.

Potsdam, July, 1945, the final war council—where a new American President, Harry S. Truman, and a new British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, learned their first lessons in the difficult task of negotiating with the Soviets and the unpromising fact of Russia’s dominance in Europe was brought home to all present.

My presence was required at all of the purely military meetings of these war councils. In addition, Presidents Roosevelt and Truman both asked me to attend many of the political sessions where only Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt (Truman at Potsdam) and a few of their top advisers sat around the conference table.

Much of this narrative is based on my daily sessions with Roosevelt, and subsequently with Truman, on military affairs and foreign policy. Most of these talks took place in the Oval Study of the White House, where so much history has been made. Sometimes they occurred aboard the President’s private car or plane, at Hyde Park, at Shangri-la, at hotels, or at sea—wherever the President happened to be. We discussed many matters outside the scope of my military duties as Chief of Staff to the President. These ranged from grave home-front problems, such as the manpower crisis, to such matters as Roosevelt’s approval of a candidate for Vice President.

As the senior officer of all American armed forces, I presided over the Joint Chiefs of Staff and transmitted to it the basic thinking of the war Presidents on vital strategic and political problems they faced in their efforts to defeat our enemies. When our country was the host, I also presided over the meetings of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. This group included the highest ranking officers of the various branches of the armed forces of the United States and Great Britain. We did not have at any time during the war any such helpful coordination with our Soviet ally, although there were a few sessions at Yalta and Teheran when the three staffs met together.

The duties of Chief of Staff to the President required careful selection of all military dispatches of sufficient importance to be read by the President. Also involved was the screening of numerous and, on occasion, insistent demands from many persons—military, diplomatic, and civilian—for conferences with the President on matters having a real or supposed military angle. It was natural that this close daily association with both war Presidents brought all manner of men and causes to my office, seeking intercession in their behalf. Among these were representatives of defeated and exiled governments, as well as our active allies, who often pleaded for more American dollars, more American arms, and sometimes for American troops.

Prior to becoming his Chief of Staff in July, 1942, President Roosevelt sent me on one of the most controversial diplomatic missions of the entire war period—that of being Ambassador to France from January, 1941, to May, 1942, during Marshal Henri Pétain’s wavering regime at Vichy.

While executing this difficult assignment I was called many things by the Axis-controlled press, none of them complimentary.

So uncertain were our relations that an escape route was kept in readiness at all times, with gasoline and supplies cached along the way should it be necessary for us to leave Vichy unexpectedly.

My association with Franklin Roosevelt began in 1913 when he moved to Washington from New York to become Assistant Secretary of the Navy in Woodrow Wilson’s Administration.

During 1915-1916, I commanded the Secretary of the Navy’s dispatch boat, the Dolphin. Roosevelt made several cruises on the Dolphin and we became good friends. I visited with him for short periods in his homes at Hyde Park and Campo Bello. He was at that time a handsome, companionable, athletic young man of unusual energy, initiative, and decision. He knew the history, details of the composition and of the operations of the United States Navy since its original establishment. Roosevelt also was a highly competent small-boat sailor and coast pilot. He had a deep affection for everything that had to do with sailing craft. During this close contact, I acquired an appreciation of his ability, his understanding of history, and his broad approach to foreign problems. There developed between us a deep personal affection that endured unchanged until his untimely death.

After our country’s formal entry into World War I in 1917, we had little contact until he as President appointed me Chief of Naval Operations in January, 1937. Thereafter we held many conferences on America’s need for an adequate sea defense. His own interest and experience, gained in eight years as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, equipped him with a splendid knowledge of the Navy’s problems.

Roosevelt was thoroughly devoted to the avoidance of war by every honorable means, but the lessons of world history with which he was so familiar had convinced him of the necessity for adequate naval preparation to prevent any invasion of the United States from overseas. He knew that such preparation had been made and was available to execute defense plans. However, a partial destruction of the American fleet by the unexpected Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor left the United States for the time being without sufficient sea power to neutralize the Navy of Japan.

Roosevelt knew that, barring an unforeseen collapse of the Nazi forces, Hitler was a threat to the very existence of our country and that war was inevitable. At a little ceremony in his study late in July, 1939, at which time Roosevelt pinned the Distinguished Service Medal on me, he remarked, “Bill, if we have a war, you’re going to be right back here helping me to run it.” Roosevelt actually feared in 1940 that war would come to us. I was then preparing to leave for Puerto Rico to become Governor of that island. War did not come until Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), at which time I was serving as Ambassador to France. When Germany and Italy declared war on us four days later (December 11) he kept me at Vichy until my recall in May, 1942, when Pierre Laval assumed control of the Pétain government. Two months later I assumed the duties of Chief of Staff to the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, an office he created to give him a personal representative in the Chiefs of Staff, who were charged with the complex task of prosecuting the war to a successful conclusion.

When Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and Vice President Truman became President, I immediately offered my resignation. He rejected this suggestion and I continued to serve Truman in the same capacity until March 21, 1949.

Working for three years in daily contact with President Truman in much the same way in which I had worked with President Roosevelt, I found him to be, by every measure of comparison, a great American.

President Truman was thoroughly honest, considerate, and kindly in his approach to problems and in his relations with his assistants.

He asked advice in regard to military matters and foreign relations as frequently as did his predecessor. He listened attentively to volunteered advice, and made positive decisions for which he assumed full personal responsibility.

His method of administration differed from that of Mr. Roosevelt in that after reaching a decision he delegated full responsibility for its execution to the department of the government charged by custom or by law with that duty. In my opinion his decisions were usually correct and advantageous to the cause of the United States. Where the results were bad, the fault was in an inefficient handling of details by departmental officials.

Mr. Roosevelt also made decisions after careful consideration of requested or volunteered advice, but he differed from Mr. Truman in that he had little confidence in some of his executive departments, and therefore took detailed action with his own hands, assisted when necessary by some of his personal secretaries. Actions that should have been prepared in draft form by some of the executive departments were frequently handed over to Harry Hopkins or to me for preparation of a draft directive and then later were brought into exact accord with his personal ideas by the President himself. This permitted President Roosevelt to be completely familiar with the details of all of his written orders and other official communications.

Under President Truman’s practice of delegating such work to the executive departments, a principle of organization in which I thoroughly believed, I did at times have difficulty in understanding the exact meaning of some departmental communications.

Both of these Presidents were in different ways splendid, outstanding Americans in a period of world crisis.

Both attained about an equal measure of success in solving difficult problems that were presented to them in great volume every day.

It was for me a splendid privilege and a high honor to be associated in my small way with both of them. Both Presidents will, in my opinion, be recorded in history as having been completely devoted to America in its successful struggle with alien enemies of our philosophy of government, and as having acquired and maintained the enduring affection of all who worked with them to the same end.

During the eventful five-year period beginning with my assignment to Vichy, I made notes from day to day. These “memos to myself” were not written with this book in mind. They were for reference to assist me in handling later tasks in the rapidly changing war situation and they were invaluable for that purpose.

They were made by me personally, in my own handwriting, and are correct in their statements of facts and dates. Any appraisals of situations and evaluations of personalities which I made in these notes and from which I shall frequently quote were based on information then available and were of course subject to human error. They were the best I could do at the time. Any messages sent in code that are used in whole or in part in these notes have been paraphrased. This has been done, not because of the information contained in the cables, but to protect the security of the codes which were used at that time.

In the hope of being of some small aid to the historians who must fit together the vast jigsaw puzzle of war history, I have been persuaded to condense from these personal records an account of my part in handling some of the pieces of that puzzle. The tedious study of warehouses full of official documents will be left to others. This is my story as I saw it.

2—CALLED TO NEW DUTY

At midnight on Friday, January 5, 1941, in the midst of what Frenchmen said was the coldest winter in ninety years, the new American Ambassador to France arrived at the provisional capital of Vichy.

I was the Ambassador. At that hour, after a dreary trip north from Madrid in a dirty, crowded train with no heat except that which could be applied internally, I probably had less enthusiasm for this new assignment than any duty required of me in forty-four years of active service to my country.

Just six weeks before, Mrs. Leahy and I had been enjoying a leisurely Sunday morning breakfast in a small guest house of La Fortaleza, the governor’s residence at San Juan, Puerto Rico, when an aide interrupted us to hand me a confidential message from President Roosevelt. It read:

“We are confronting an increasingly serious situation in France because of the possibility that one element of the present French Government may persuade Marshal Pétain to enter into agreements with Germany which will facilitate the efforts of the Axis powers against Great Britain.

“There is even the possibility that France may actually engage in war against Great Britain and in particular, that the French Fleet may be utilized under the control of Germany.

“We need in France at this time an Ambassador who can gain the confidence of Marshal Pétain, who at the present moment is the one powerful element of the French Government who is standing firm against selling out to Germany.

“I feel that you are the best man available for this mission. You can talk to Marshal Pétain in language which he would understand, and the position which you have held in our own Navy would undoubtedly give you great influence with the higher officers of the French Navy who are openly hostile to Great Britain.

“I hope, therefore, that you will accept the mission to France and be prepared to leave at the earliest possible date.”

Roosevelt’s message was a complete surprise. Some months after reaching the statutory retirement age of sixty-four in 1939, I had completed my work as Chief of Naval Operations and the President had appointed me as Governor of Puerto Rico.

We were not then in the war, but Roosevelt feared acutely that we w...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- 1-I WAS THERE

- 2-CALLED TO NEW DUTY

- 3-THE AXIS MAKES ADDITIONAL DEMANDS

- 4-RUSSIAN BAROMETER

- 5-COMPLICATIONS IN FRENCH AFRICA

- 6-BATTLE STATIONS

- 7-MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

- 8-HIGH COMMAND AT WORK

- 9-FULL SPEED AHEAD ON “TORCH”

- 10-DARLAN DELIVERS

- 11-CASABLANCA AND WASHINGTON CONFERENCES; DISTRESS SIGNALS FROM CHINA

- 12-FIRST QUEBEC CONFERENCE; PREPARATION FOR “OVERLORD”

- 13-THE AXIS BREAKUP BEGINS

- 14-CAIRO, TEHERAN, AND A BROKEN PROMISE

- 15-EYES ON THE PACIFIC; INVASION OF NORMANDY

- 16-PACIFIC WAR PROBLEMS; SECOND QUEBEC CONFERENCE

- 17-PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1944; PROSPECTS OF VICTORY IN EUROPE

- 18-YALTA

- 19-ILL OMENS FOR PEACE

- 20-TRUMAN TAKES COMMAND

- 21-ALLIED CONTROVERSIES; PREPARATIONS FOR POTSDAM

- 22-POTSDAM

- 23-ATOM BOMBS, GERMS-AND PEACE

- APPENDIXES

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER