- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

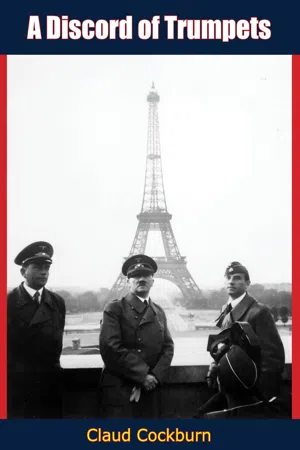

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A LEGENDARY NEWSPAPERMAN WHO IS NAMED CLAUD COCKBURN (pronounced Coburn) and who has been called many things (most of the pronounced abusively) by well-known personages all over the world for a quarter of a century.

For some years before World War II he was the diplomatic correspondent of the (London) "Daily Worker." For even more years he was a foreign correspondent of "The Times" (also of London).

He founded and wrote "The Week," a mimeographed anti-Fascist periodical which he says "was unquestionably the nastiest-looking bit of work that ever dropped onto a breakfast table." It started with seven subscribers and in two years numbered among its readers most of the diplomats of Europe, many bankers and senators, Charlie Chaplin, King Edward VIII and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin once listed him as one of the 269 most dangerous Reds alive. In the same week, a Czech Communist named Otto Katz was hanged in Prague after confessing that he had been recruited to the cause of anti-Communism by Colonel Cockburn of the British Intelligence Service.

Here is what the man himself says about how funny, how tragic and how fascinating he found life in London, Berlin, New York and Washington in the years between two world wars. Some of these stories have appeared in "Punch," but this is a complete text of what the author has so far written down about himself and his legend. It is full of wit, and irreverence, and surprising joyfulness. It is a little like the glass of champagne the author learned to appreciate in "the little moment which remains between the crisis and the catastrophe."

For some years before World War II he was the diplomatic correspondent of the (London) "Daily Worker." For even more years he was a foreign correspondent of "The Times" (also of London).

He founded and wrote "The Week," a mimeographed anti-Fascist periodical which he says "was unquestionably the nastiest-looking bit of work that ever dropped onto a breakfast table." It started with seven subscribers and in two years numbered among its readers most of the diplomats of Europe, many bankers and senators, Charlie Chaplin, King Edward VIII and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin once listed him as one of the 269 most dangerous Reds alive. In the same week, a Czech Communist named Otto Katz was hanged in Prague after confessing that he had been recruited to the cause of anti-Communism by Colonel Cockburn of the British Intelligence Service.

Here is what the man himself says about how funny, how tragic and how fascinating he found life in London, Berlin, New York and Washington in the years between two world wars. Some of these stories have appeared in "Punch," but this is a complete text of what the author has so far written down about himself and his legend. It is full of wit, and irreverence, and surprising joyfulness. It is a little like the glass of champagne the author learned to appreciate in "the little moment which remains between the crisis and the catastrophe."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Discord of Trumpets by Claud Cockburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

IN our little house, the question was whether the war would break out first, or the revolution. This was around 1910.

That period before World War I has since got itself catalogued as a minor Golden Age. People living then are said to have had a sense of security, been unaware of impending catastrophe, unduly complacent.

In our neighborhood, they worried. They thought it was the Victorians who had had a sense of security and been unduly complacent.

There were war scares every year, all justified. There was the greatest surge of industrial unrest ever seen. There was a crime wave. The young were demoralized. In 1911, without any help from television or the cinema or the comics, some Yorkshire schoolboys, irked by discipline, set upon an unpopular teacher and murdered him.

Naturally, alongside those who viewed with alarm, there were those who thought things would probably work out all right. Prophets of doom and Pollyannas, Dr. Pangloss and Calamity Jane—all lived near us in Hertfordshire in those years, and I well remember being taken to call on them all on fine afternoons in the open landau, for a treat.

At home the consensus was that the war would come before the revolution.

This, as can be seen from the newspaper files, was not the most general view.

At our house, however, people thought war was not any nicer than revolution, but more natural.

It was in 1910 that my father desired me to stop playing French and English with my tin solders and play Germans and English instead. That was a bother, for there was a character on a white horse who was Napoleon—in fact, a double Napoleon, because he was dead Napoleon, who fought Waterloo, and also alive, getting ready to attack the Chiltern Hills where we lived. It was awkward changing him into an almost unheard-of Marshal von Moltke.

Guests came to lunch and talked about the coming German invasion. On Sundays, when my sister and I lunched in the dining room instead of the nursery, we heard about it. It spoiled afternoon walks on the hills with Nanny, who until then had kept us happy learning the names of the small wild flowers growing there. I thought Uhlans with lances and flat-topped helmets might come charging over the hill any afternoon now. It was frightening, and a harassing responsibility, since Nanny and my sister had no notion of the danger. It was impossible to explain to them fully about the Uhlans, and one had to keep a keen watch all the time. Nanny was no longer a security. (An earlier Nanny had herself been frightened on our walks. She was Chinese, from the Mongolian border, and she thought there were tigers in the Chilterns.)

One night at haymaking time when the farm carts trundled home late, I lay awake in the dusk and trembled. Evidently they had come, and their endless gun carriages were rolling up the lane. My sister said to go to sleep; it was all right because we had a British soldier staying in the house. This was Uncle Philip, a half-pay major of Hussars whose hands had been partially paralyzed as a result of some accident at polo.

His presence that night was a comfort. But his conversation was often alarming, particularly after he had been playing the War Game.

In the garden there was a big shed, or small barn, and inside the shed was the War Game. It was played on a table a good deal bigger, as I recall, than a billiard table, and was strategically scientific. So much so, indeed, that the game was used for instructional purposes at the Staff College. Each team of players had so many guns of different caliber, so many divisions of troops, so many battleships, cruisers and other instruments of war. You threw dice and operated your forces according to the value of the throw. Even so, the possible moves were regulated by rules of extreme realism.

The game sometimes took three whole days to complete, and it always overexcited Uncle Philip. The time he thought he had caught the Japanese admiral cheating he almost had a fit—not because the Japanese really was cheating, as it turned out, but because of the way he proved he was not cheating.

The admiral and some other Japanese officers on some sort of goodwill mission to Britain had come to lunch and afterward played the War Game. As I understand it, they captured from the British team—made up of my father, two uncles and a cousin on leave from the Indian Army—a troopship. It was a Japanese cruiser which made the capture, and, at his next move, the admiral had this cruiser move the full number of squares which his throw of the dice would normally have allowed it. Uncle Philip accused him of stealthily breaking the rules. He should have deducted from the value of his throw the time it would have taken to transfer and accommodate the captured soldiers before sinking the troopship. He found the proper description of this cruiser in Jane’s Fighting Ships and demonstrated that it would have taken a long time—even in calm weather—to get the prisoners settled aboard.

The admiral said, “But we threw the prisoners overboard.” He refused to retract his move.

Uncle Philip hurled the dice box through the window of the shed and came storming up to the house. Even in the nursery could be heard his curdling account of the massacre on the troopship.

“Sea full of sharks, of course. Our men absolutely helpless. Pushed over the side at the point of the bayonet. Damned cruiser forging ahead through water thickening with blood as the sharks got them.”

Even when the Japanese fought on the British side in World War I Uncle Philip warned us not to trust them.

His imagination was powerful and made holes in the walls of reality. He used to shout up at the nursery for someone to come and hold his walking stick upright at a certain point on the lawn while he paced off some distances. These were the measurements of the gun room of the shooting lodge he was going to build on the estate he was going to buy in Argyllshire when he had won £20,000 in the Calcutta Sweep. Sometimes he would come to the conclusion that he had made this gun room too small—barely room to swing a cat. Angrily he would start pacing again and often find that this time the place was too large. “I don’t want a thing the size of a barn, do I?” he would shout.

Once, some years earlier, his imagination functioned so powerfully that it pushed half the British fleet about. That was at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, when the fleet was drawn up for review at Spithead in the greatest assembly of naval power anyone had ever seen. Uncle Philip and my father were invited by the admiral commanding one of the squadrons to lunch with him on his flagship. An attaché of the admiral commanding-in-chief was also among those present.

Halfway through lunch Uncle Philip began to develop an idea. Here, he said, was the whole British fleet gathered at Spithead, without steam up, immobile. Across there was Cherbourg. (At that time the war, when it came, was going to be against the French.) Well, suppose one night—tonight, for instance—some passionately Anglophobe commander of a French torpedo boat were to get the notion of dashing across the Channel in the dark and tearing between the lines of the great ships, loosing off torpedoes? The ships helpless, without steam up. In twenty minutes, half of them sinking. In an hour, Britain’s power reduced to the level of Portugal’s. By dawn, the Solent strewn with the wreckage of an empire. Before noon, mobs crazed with triumph and wine sweeping along the Paris boulevards, yelling for the coup de grâce.

He spoke of this, my uncle said, not as an idle speculation but because he happened to have recalled, on his way to this lunch, that in point of fact a French officer, just mad enough to carry out such a project, was at this moment in command of a torpedo boat at Cherbourg. (His voice, as he said this, compelled a closer attention by the admiral and the attaché of the commander-in-chief.)

Certainly, he said: he had met the man himself, a Captain Moret, a Gascon. Hot-blooded, hating the English for all the ordinary French reasons; and for another reason, too: his only sister—a young and beautiful girl, Uncle Philip believed—had been seduced and brutally abandoned by an English lieutenant—name of Hoadley, or Hoathly—at Toulon. A fanatic, this Moret. Had a trick of gesturing with his cigar—like this (Uncle Philip sketched the gesture)—as he, Moret, expatiated on his favorite theory, the theory of the underrated powers of the torpedo boat as the guerrilla of the sea.

“And there,” said Uncle Philip, in a slightly eerie silence, “he is.” He nodded ominously in the direction of Cherbourg.

On the way back to Cowes in the admiral’s launch, my father upbraided Uncle Philip. A nice exhibition he had made of himself—a mere major of Hussars, lecturing a lot of admirals and captains on how to run their business. Also they had undoubtedly seen through this yarn, realized that this Moret was a figment of Uncle Philip’s imagination, invented halfway through the fish course. Then, and during the remainder of the afternoon and early evening, Uncle Philip was abashed, contrite. After dinner that evening they walked by the sea, taking a final look at the fleet in the summer dusk. Silently my uncle pointed at the far-flung line. Every second ship in the line was getting up steam.

People told Uncle Philip that if he would employ his gift of the gab in a practical way, not spend it all in conversation but take to writing, he would make a fortune—like Stanley Weyman or someone of that kind. It seemed a good idea, and while waiting for the Calcutta Sweep to pay off he wrote, and published at the rate of about one a year, a number of historical romances. They included Love in Armour, A Gendarme of the King, The Black Cuirassier and A Rose of Dauphiny. It was unfortunate from a financial point of view that he had a loving reverence for French history, which he supposed the library subscribers shared. The historical details of his stories were to him both fascinating and sacred. He refused to adjust by a hairsbreadth—in aid of suspense, romance or pace of action—anything whatsoever, from an arquebus to a cardinal’s mistress. Once you were past the title, you were on a conducted tour of a somewhat chilly and overcrowded museum.

However, he did make enough out of these books to feel justified in buying a motorcar, in the days when that was a daring and extravagant thing to do. He reasoned that since the Sweep would ultimately provide a motorcar as a matter of course, it was foolish to spend time not having a motorcar just because the draw was still nine months off.

He was not its possessor for long. He was superstitious. The car was of a make called Alldays. He showed it to my father. My father was against motorcars. Some people of his age were against them because they went too fast. My father disliked them because they did not go fast enough. He took the view that if people were to take the trouble to give up horses and carriages and go about in these intricate affairs instead, it was only reasonable that the machines, in return, should get them to wherever they wanted to be in almost no time—a negligible, unnoticeable time. The fact that even with one of these vaunted motorcars you still took hours and hours to get from, say, London to Edinburgh struck him as disgusting and more or less fraudulent. Later he felt the same way about airplanes. He was thus not enthusiastic about Uncle Philip’s motorcar, and when he saw the maker’s name on the bonnet he unkindly murmured the quotation “All days run to the grave.”

Uncle Philip took fright and sold the car immediately at a heavy loss. Of this I was glad, not because I thought the car would run him to his grave but because I thought it would get him into a dungeon. He had a chauffeur called Basing, and I once heard somebody say, “That man Basing drives too fast.” He had been known to exceed the speed limit of twenty miles per hour. In those days when people spoke of motorcars they spoke also of police traps. My idea of the police was simple and horrifying. I thought they would soon manacle Uncle Philip and leave him to rot in a cell. We should never see him again.

This is one of those griefs which are caused to children by the seemingly frantic irresponsibility and ignorance of adults. When I was seven I read the opening lines of some book of elementary science which said, “Without air we cannot live.” I crept about the house opening windows and repeatedly reopening them secretly after bewildered and seemingly suicidal grownups had closed them against the bitter autumn winds.

Real life, like curry—which he ate Anglo-Indian fashion, so hot it would have charred a real Indian’s stomach—was never quite sharp enough for Uncle Philip. The weary present he made endurable to his taste by a sort of incantation. He recited old French ballads aloud as he walked to the village, or simply shouted agreeably sonorous words. You asked him where he was going and he peered through his monocle and shouted, “I am on my way to the headquarters of his Supreme Excellency the Field Marshal Ghazi Ahmed Mukhta Pasha.” When the past tasted a little flat, he peppered it artificially. No one was safe from his cookery. He was talking to me once about his grandfather—a worthy officer, I believe, of the Black Watch—who had died peacefully but at a rather early age. Finding the story dull, Uncle Philip told me that in reality, though it had been hushed up, his grandfather had shot himself in melodramatically scandalous circumstances. I think that at the time he believed he was actually doing the deceased a good turn—making him more interesting than he had, in fact, managed to be. Uncle Philip was my mother’s brother, and I asked her about it. She was in a dilemma. She wished to deny it as authoritatively as possible. On the other hand, she hesitated to tell a child of seven that his uncle was a monstrous liar.

As for the future, Uncle Philip seasoned it with the Calcutta Sweep and the imminence of a very interesting war. As things turned out, he never did win the Sweep, and the war was no fun either. He got himself back into the army, despite his crippled hands, but the cold and damp undermined his health and laid him low.

The theoretical basis of Uncle Philip’s belief that war was coming soon was quite simple. He thought any government which supposed itself to have a reasonable advantage in armaments and manpower over its neighbors or rivals would go for them as soon as it was convinced that this was the case, and provided the weather was suitable for the type of campaign its armies preferred. In this view he had the concurrence of my Uncle Frank, my father’s elder brother, who in other respects was so different from Uncle Philip that he might have been brought up on a different planet. But he did enjoy the War Game, finding it more sensible than cards, and even made, in collaboration with Uncle Philip, some suggestions for changes in the rules which were sent to the Staff College, or whatever the strategic institution was that used the game, and I believe adopted there.

He was a banker and a Canadian, and he took, uninhibitedly, the view that the world was a jungle and civilization a fine but flimsy tent which anyone would be a fool either not to enjoy or to treat as a secure residence. Compared to the rest of the family he was rich. Enormously so, I thought at the time, for there seemed to be nothing he could not afford, and I was told once that he actually had a lot more than Uncle Philip would have if he drew the winning ticket in the Sweep.

During those years, when we were moving about southern England looking, my father kept assuring me, for somewhere to settle down permanently, Uncle Frank was a frequent visitor, fleeting, but as impressive as a big firework.

His headquarters were at Montreal, but the place where he felt at home was Mexico. He spent a lot of time there, helping to organize some kind of revolution or counter-revolution—nominally in the interests of the bank, but mainly because that was the kind of work he liked. The details were never fully revealed to us. This was due partly to discretion, partly to the fact that the precise lines and objectives of the undertaking—which once had been a quite simple business of violently overthrowing the government—had become year by year increasingly complex and uncertain.

Nobody seemed to know just whose side anyone was on, which generals and politicians and rival financiers and concessionaires were good—that is to say, pro-Uncle Frank—and which bad....

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER