eBook - ePub

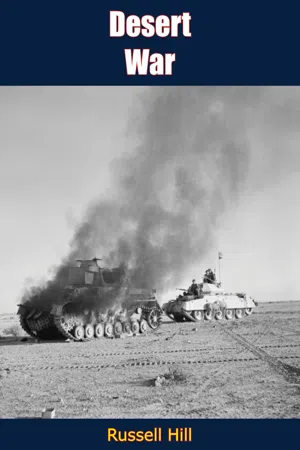

Desert War

About this book

This is the kind of book you've been waiting for about the war—a book by a correspondent who was in the thick of the actual fighting, in the front lines and sometimes ahead of them. Only in North Africa, because of the strange fluid quality of desert tactics, have correspondents actually been allowed to see men in battle—to attach themselves to fighting units and to move constantly with those units. It is this which gives its unique quality to Russell Hill's account of the second British invasion of Cyrenaica.

Mr. Hill is the brilliant young Cairo correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune. He knew the campaign was going to start days before it actually did; and he was permitted to inspect oasis outposts, supply dumps, and even Tobruk itself, still surrounded and still magnificently holding out. When the big "flap" began, Hill moved out with a forward unit, and was immediately plunged into that made swirling melee that is deeper fighting, and to which no description short of Hill's own can do justice.

If you were puzzled by the reports which came for days from Sidi Rezegh, where Rommel made his stand and his escape; if your heart leapt at the relief of Tobruk; if your hopes were raised then the British reached El Agheila, and were dashed down again when Rommel lashed back to Tobruk and the Egyptian border—you will find all the answers and the explanations in this book.

With 14 illustrations and 5 maps.

Mr. Hill is the brilliant young Cairo correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune. He knew the campaign was going to start days before it actually did; and he was permitted to inspect oasis outposts, supply dumps, and even Tobruk itself, still surrounded and still magnificently holding out. When the big "flap" began, Hill moved out with a forward unit, and was immediately plunged into that made swirling melee that is deeper fighting, and to which no description short of Hill's own can do justice.

If you were puzzled by the reports which came for days from Sidi Rezegh, where Rommel made his stand and his escape; if your heart leapt at the relief of Tobruk; if your hopes were raised then the British reached El Agheila, and were dashed down again when Rommel lashed back to Tobruk and the Egyptian border—you will find all the answers and the explanations in this book.

With 14 illustrations and 5 maps.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I—THE SOUTHERN OASES

THERE is no very good reason why that barren waste which stretches from the outskirts of Alexandria to the frontiers of Libya should be called the Western Desert. The same expanse of nothingness reaches on to the west for a score of hundreds of miles beyond Egypt. An American looking at the map of Africa would be likely to call the small portion which lies within the boundaries of Egypt the Eastern Desert. But for those who live in Egypt it is the Western Desert, and the Eastern Desert is the barren Sinai Peninsula and the sands beyond.

This Western Desert, for so we must call it, is three hundred miles in width, and penetrates inland from the southern coast of the Mediterranean more miles than we need consider. It is a military reservation. Although it is a part of Egypt, few of the Egyptians huddled within the narrow but fertile confines of the Nile Delta have ever seen more than the edge of it. In October of last year it was a great army camp. The 8th Army of His Britannic Majesty’s forces had made it a home and covered it with scattered tents and trucks and with a myriad of tracks, crossing one another at crazy angles, going from nowhere to nowhere. There were no towns, no trees, no rivers, no mountains, but only characterless expanses of limestone covered in places by hard, packed sand. There were wadis—gullies cut by torrents, which not more than once in a year, sprung from a sudden thunderstorm and rushing down from the high places, flooded the low ground near the coast. Here it was that a hundred thousand men or more lived and made ready to fight.

Into this desert country I drove one day in October 1941, leaving Cairo behind, passing Alexandria, going westward along the coast. I did not know it at the time, but it happened to be exactly one month before the beginning of the long-planned and long-awaited offensive that was to take these fighters out of the Western Desert into another desert farther west, and then beyond that into the green fields of Cyrenaica, one of the last evidences that the land along the northern coast of Africa had once been so rich that it was necessary to sow a part of it with salt to prevent crops from growing there.

With three other newspaper reporters I drove in an army station wagon to a point in the desert which for reasons of military security must still be nameless. It was the headquarters of this 8th Army. After hours of speeding along a hard, surfaced road within sight of the sea, our car turned off onto a track which took us shortly to our camp. War correspondents attached to the British forces belong to a unit called Public Relations, whose duty it is to act as liaison between the correspondents and the rest of the army. To the Public Relations camp we came. It was a group of some dozen tents and two dozen vehicles, dispersed and camouflaged in such a way as to make them difficult targets from the air. The center of the camp was the officers’ mess. Two pits had been dug, each twenty feet square and three feet deep, connected by a narrow trench. Sandbags had been piled around the edges of the pits, and a tent hung over each one. The result was two good-sized rooms connected by a narrow corridor. One was the combined writing-room and dining-room, accommodating thirty people at three rough tables with wooden benches. The second room was the bar. There the officers and correspondents sat on camp chairs or sofas made of sandbags and offered one another whisky and water, gin and lime, or beer as casually as if they had been at one of the most comfortable bars in Cairo.

After reporting our arrival to Staff Captain Madison, who was in charge of the camp, we were allotted to our tents, each large enough to accommodate two or three. Our “kit” was taken out of the car, we set up our camp beds, washed in a canvas basin, made our temporary homes as comfortable as possible, and went to the mess. There was time before supper to talk over plans for visiting the forward areas.

It happened that a censorship ban on any mention of the oases of Siwa and Giarabub had recently been lifted. Several of the correspondents were anxious to visit these places, expecting them to provide good “color” stories. Moreover, it was thought that when the offensive began, Giarabub, which lies across the Libyan frontier, 125 miles from the coast, might be used as a starting-point for some of the operations. For a trip to these two places extensive preparations were necessary. Trucks had to be loaded with at least a week’s supplies of food and water, and with enough gasoline for traveling several hundred miles across the desert.

Captain Madison told us the trip could not be “laid on” until Monday morning. It was then Saturday evening. We would have to spend Sunday at headquarters. A newspaperman who is used to working against deadlines and jealously counting every hour is impatient at first at such delays. But he soon learns that they are inevitable and becomes reconciled to spending a week on a trip which may yield nothing more than one or two feature stories. Later on, when the campaign had started, we all felt well recompensed because the knowledge we had gained of the nature of the terrain and the composition of the forces gave us an invaluable background.

We planned to devote Sunday to getting provisions and completing our preparations. We had time to go down to a little bay and swim in the salty water. Hundreds of troops were doing the same, diving naked into the surf, and coming out to lie in the sun on the hard, warm sand. Although the nights are cold in the desert in October, the water is still warm and the sun is hot enough in the middle of the day to make bathing a real pleasure. Overhead we watched Tomahawk and Hurricane fighters practicing their dives and turns and fighting sham battles with one another. Now and then a bomber or transport plane would fly low and land on a near-by airfield. Two soldiers with tin hats stood by an anti-aircraft gun at the top of a rise overlooking the water. In the midst of all this preparation for war, one felt strangely peaceful lying there on the beach, watching the waves that came in against the shore, and the white surf that went up as the water broke against the rocky islands at the entrance to the bay.

In the afternoon I sat in the cool of the tent and read General Sir Archibald Wavell’s biography of Field Marshal Sir Edmund Allenby. Wavell had learned much from Allenby. Reading the descriptions of the older general’s campaigns, I could see that the biographer had carefully noted the simple lessons of military strategy they taught. Twenty years later he had faithfully followed Allenby’s principles and won a victory which was classically beautiful in its execution and tremendously important in its consequences, in spite of the reverses which followed.

On the Monday morning we rose early and our caravan started on its trek into the interior of the desert. It was composed of two one-ton Ford trucks, carrying three war correspondents, two officers, and two army drivers, with provisions sufficient for a week.

Our conducting officer was Captain Crooke of the Rifle Brigade, one of the high-class English regiments, whose members wear a green field-cap with a green button. The most prominent feature of his slightly chubby, reddish face was a flourishing walrus mustache. He was genial and cheerful, but told us he would rather be with his regiment than be taking war correspondents on a conducted tour of the desert. He didn’t see why we couldn’t find our way around by ourselves, and neither did we. Having reached agreement on that point, we were able to proceed on our trip with a spirit of goodwill prevailing all around. The second officer was Lieutenant Bradbury, the representative of Parade, a weekly magazine published in Cairo for the troops.

The two other correspondents were British. Alan Moorehead, of the Daily Express, with whom I had worked during the campaigns in Syria and Persia, is one of the ablest writers among the newspapermen in the Middle East. Alaric Jacob, of Reuter’s news agency, had spent several years in the United States as Washington correspondent. Both were congenial companions.

Before heading south into the desert we drove along the road to Mersa Matruh to pick up some final provisions. The little town, which had once been an attractive seaside resort, was now a battered ruin. From the top of a hill we looked down on what remained of its white houses, which must once have presented an attractive sight, with the green palms and the blue waters of the bay. Mersa Matruh now was nothing but the cornerstone of a defensive line running south to the impassable Qattara Depression If the enemy ever broke through the forward defenses, it was planned to hold him here.

We passed through barbed-wire entrenchments and mine-fields, then left the coastal road and took the Siwa Track and, following in the wake of innumerable convoys, headed into the void. Signposts pointed to “Charing Cross” and “Piccadilly Circus.” The English tommies had named these junctions of desert tracks after places back home where they wished they could be.

Our track rose quickly to 650 feet above sea level, then proceeded in a straight line along a featureless plateau for mile after mile. When we stopped for lunch, swarms of flies settled on us and on our food. They seemed to spring from nowhere, and there was no avoiding them. While the truck was in motion they did not annoy us, and in the cool of the evening they stayed hidden away; but during the long hot days of spring and summer and autumn they are an ever-present curse to the soldier who has no other home but the desert. For lunch the drivers opened a couple of tins of bully beef (corned beef from the Argentine) and brought out a loaf of bread and a can of margarine. We poured ourselves a drink of gin, lime juice, and water.

Within half an hour we were back in the trucks, moving toward the southwest. Captain Crooke sat in the front of the first truck with the driver. One of the correspondents sat in the back with the kit and provisions. Someone else could sit with the driver of the second truck, while the other two members of the party arranged themselves on the two seats in back. This was not an unpleasant way of traveling, for one got the full benefit of the sun and was able to get a good view of what was going on, if anything.

An hour before sundown we stopped the vehicles and camped down for the night. We had looked for some kind of hollow where we would be sheltered from the wind, but all we could find was the faintest hint of a dip. The trucks were parked close together, and the drivers began preparing the evening meal while the correspondents wrestled with unfolding their camp beds and making them up. I was much envied because in addition to the usual blankets I had a pushtin, a heavy sheepskin coat I had picked up in Persia. This useful article was the pièce de résistance of my bedding.

The dinner had to be prepared quickly, for as a matter of general precaution no fires were allowed after dark, even though we were far from the enemy positions. The usual thing to make was stew, and that was what we had. The driver-cook took an empty gasoline can and cut it in two with the can-opener. The bottom half he filled with sand, on which gasoline was poured. A lighted match was thrown in, and the whole thing went up with a blaze. The other half of the empty can was put over the fire and while it was still hot, water was poured in. This scalding is supposed to take out the taste of the gasoline. The old can could now be used as a pot for cooking stew. It was washed out, and fresh water poured in. Bully beef was the basis of the stew, but we were fortunate in being able to add onions, potatoes, a can of soup, a few canned vegetables, and some Worcestershire sauce. The finished product was hot and plentiful, and it tasted pretty good to us after a day in the back of the truck. We ate it sitting on our cots, watching night fall over the cool, empty desert. We opened a can of peaches. Then the stars began to come out. We watched them grow brighter, and felt the biting chill of the desert night, and sipped whisky to keep the blood circulating. We had nothing to do but talk, for we could make no light. We spoke perhaps of other campaigns, of Greece and Syria, of the magnificent showing of the Soviet Army, or the prospects of the next campaign in the desert. We had been sitting there a long time and it was seven thirty. The thing to do seemed to be to go to bed. It was odd—in Cairo the evening would not yet have begun.

There is something about living in the desert that makes one sleep longer. I lay in bed looking up at the very many, very bright stars, and the next thing I knew, I was watching the sun come up into a pale sky. I had slept well, but did not feel at all like getting up. For one thing, it seemed desperately cold. I jumped out, tore off my pajamas, jumped into my uniform, and started running in a wide circle around the camp to warm myself. By the time I got back, the drivers had a fire going and were preparing tea. Two cups of water for washing, two cups of water for tea. We ate sausages and bread and margarine and jam. Another can of fruit was opened. That was not part of the rations. Hard rations are bully beef, biscuits, margarine, tea, sugar, jam, sometimes canned meat and vegetables. The rest was whatever we chose to buy and bring along. It could not be too much because there wasn’t room.

As we drove on farther away from the coast, the appearance of the desert changed. It was no longer flat, but varied instead, with shelf-like formations of limestone. One had to be careful to stick to the track. We were gradually descending from the slight elevation of the plateau and by ten o’clock on that second morning were in sight of the oasis of Siwa, a large patch of greenery below the level of the sea. It looked beautiful after the many miles of dry, drab country through which we had come. Pools of water, hundreds of green date palms, the mosques and houses of the town. A few Bren gun carriers were rumbling across a flat stretch. The local Arabs were dressed in their best and most colorful costumes, which were clean in honor of the annual Moslem feast of Bairam. That is their Christmas, and they seemed to think we owed them a Christmas present. At least they asked for “Bairam baksheesh”

Our first visit was to Captain Levinstein, the political officer. He represented the Army in all dealings with the local population of 5000 Senusi. That had been his job for years; he knew Arabic and knew the Arabs. He seemed to enjoy their respect. While we were sitting with him someone would come up on a business errand, and Captain Levinstein would speak to him rapidly in Arabic for a minute and then dismiss him.

From the captain we heard anecdotes about the behavior of the townsmen. One woman had become rather notorious on account of her promiscuity. The elders of Siwa applied to Captain Levinstein to have her sent away. She was immoral, they said. There was no objection to her improving her worldly condition in any way she saw fit, but when she went as far as to stand in the middle of the village square wearing trousers, she had outraged all decency and deserved to be run out of town!

Captain Levinstein was more than willing to lead us on a sightseeing tour of his oasis. We had come to inspect the military installations, but were glad to take in the other sights of a place that is too far from the centers of Western civilization to be popular with tourists. We had been rather surprised to discover how little there was of military interest in Siwa. On the trip down we had seen great caravans of trucks crossing the desert. From dark hints that had been dropped at Army Headquarters recently we had been led to believe that Siwa might be used as a base for a daring raid across southern Cyrenaica, once the offensive began. It seemed, however, that nothing more was being done than to maintain a force sufficient to garrison the place and defend it in case of attack. Perhaps there would be more to see in Giarabub.

Guided by Captain Levinstein, who obviously knew everything worth knowing about Siwa, and a great deal more, we visited in rapid succession a dead village, the remains of the Temple of Ammon Ra, and Cleopatra’s Well. The well was a circular pond of deep, clear water, and owed its name to the fact or legend that Cleopatra bathed in it when she spent holidays in Siwa with her Roman lover, Mark Antony. Mersa Matruh was another favorite resort where the lovers enjoyed themselves while those more ambitious worked to gain dominion over Egypt and the Empire. The ruined temple was not too impressive, the most interesting thing about it being that the Emperor Alexander had made a trip of several weeks to consult the oracle there after he had conquered Egypt. The village of the dead was a hill of caves covered with the ruins of small stone houses. Where the ancient Egyptians were buried, the moderns lay in hiding from enemy bombing planes.

Later in the afternoon, we visited the major who commanded an offensive post operating far into the desert. The Germans and Italians had their camps strung along the coast and knew little about the interior of the desert. The British, on the other hand, gained useful information and sometimes took prisoners or did some damage to the enemy by sending motorized patrols on long sweeps into what was technically enemy territory. The knowledge gained in this way proved of extreme value later on. The major, a tall, active man, was typical of many of the younger officers in the British and particularly the Dominion forces. Obviously his mind was alert, and open ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- MAPS

- INTRODUCTORY

- CHAPTER I-THE SOUTHERN OASES

- CHAPTER II-THE FRONTIER AREA

- CHAPTER III-TOBRUK UNDER FIRE

- CHAPTER IV-THE MEN IN COMMAND

- CHAPTER V-BRITISH BLITZ

- CHAPTER VI-“ALL OF OUR OWN AIRCRAFT RETURNED SAFELY”

- CHAPTER VII-“STRATEGIC WITHDRAWAL”

- CHAPTER VIII-TOBRUK WINS FREE

- CHAPTER IX-BATTLE AT GAZALA

- CHAPTER X-ADVANCE FROM DERNA

- CHAPTER XI-CHRISTMAS IN BENGASI

- CHAPTER XII-SECOND WITHDRAWAL

- CONCLUSION

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Desert War by Russell Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.