- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

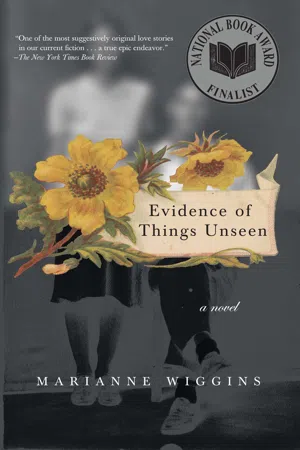

This poetic novel, by the acclaimed author of John Dollar and Properties of Thirst, describes America at the brink of the Atomic Age. In the years between the two world wars, the future held more promise than peril, but there was evidence of things unseen that would transfigure our unquestioned trust in a safe future.

Fos has returned to Tennessee from the trenches of France. Intrigued with electricity, bioluminescence, and especially x-rays, he believes in science and the future of technology. On a trip to the Outer Banks to study the Perseid meteor shower, he falls in love with Opal, whose father is a glassblower who can spin color out of light.

Fos brings his new wife back to Knoxville where he runs a photography studio with his former Army buddy Flash. A witty rogue and a staunch disbeliever in Prohibition, Flash brings tragedy to the couple when his appetite for pleasure runs up against both the law and the Ku Klux Klan. Fos and Opal are forced to move to Opal’s mother’s farm on the Clinch River, and soon they have a son, Lightfoot. But when the New Deal claims their farm for the TVA, Fos seeks work at the Oak Ridge Laboratory—Site X in the government’s race to build the bomb.

And it is there, when Opal falls ill with radiation poisoning, that Fos’s great faith in science deserts him. Their lives have traveled with touching inevitability from their innocence and fascination with "things that glow" to the new world of manmade suns.

Hypnotic and powerful, Evidence of Things Unseen constructs a heartbreaking arc through twentieth-century American life and belief.

Fos has returned to Tennessee from the trenches of France. Intrigued with electricity, bioluminescence, and especially x-rays, he believes in science and the future of technology. On a trip to the Outer Banks to study the Perseid meteor shower, he falls in love with Opal, whose father is a glassblower who can spin color out of light.

Fos brings his new wife back to Knoxville where he runs a photography studio with his former Army buddy Flash. A witty rogue and a staunch disbeliever in Prohibition, Flash brings tragedy to the couple when his appetite for pleasure runs up against both the law and the Ku Klux Klan. Fos and Opal are forced to move to Opal’s mother’s farm on the Clinch River, and soon they have a son, Lightfoot. But when the New Deal claims their farm for the TVA, Fos seeks work at the Oak Ridge Laboratory—Site X in the government’s race to build the bomb.

And it is there, when Opal falls ill with radiation poisoning, that Fos’s great faith in science deserts him. Their lives have traveled with touching inevitability from their innocence and fascination with "things that glow" to the new world of manmade suns.

Hypnotic and powerful, Evidence of Things Unseen constructs a heartbreaking arc through twentieth-century American life and belief.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evidence of Things Unseen by Marianne Wiggins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

…when seamen fall overboard, they are sometimes found, months afterwards, perpendicularly frozen into the hearts of fields of ice, as a fly is found glued in amber.HERMAN MELVILLE, Moby-Dick, “The Blanket”

radiance

On the night that they found Lightfoot, the stars were falling down.

All along the pirate coast the lighthouse keepers cast their practiced eyes into the night, raking dark infinity with expectant scrutiny the way the lighthouse beams combed cones of light over the tillered sea.

Over the Outer Banks, from the eastern constellation Perseus, shooting stars like packet seeds spilled across the sky, tracing transits of escape above the fourteen lighthouses from Kitty Hawk and Bodie Light to Hatteras and Lookout.

It was the yearly August meteor shower and Fos had driven out from Tennessee across the Smokies to the brink of the Atlantic for the celestial show as he’d done each August for the last fifteen years ever since he’d shipped home from France in ’19, once the War was over. He and fifteen other sons from Dare County had been among the first recruits to go across the North Atlantic in ’18 for valor, decency, and hell like they’d never known. Not one among them who survived was proud of it in any way that didn’t cast a shadow back across his pride. Fos himself, by accident, had been a sparker in the field, an incendiary artist, and he’d been brilliant at it. He’d always had an interest in what made things light up, made things radiate, but he never knew he had a latent genius like a fuse, a flare for fireworks, until they handed him a uniform and stood him up in front of a regimental officer and asked him what, if anything, he was good at doing. I’m good at making things light up, Fos said. Looking at the open file on the camp table between them, Fos watched the R.O.’s pen stall where Fos’s name was written on the page. You mean explosives? the R.O. said.

—um no sir.

The pen still stalled.

—chemicals? the R.O. pressed.

—radiance, Fos explained.

They put him in Artillery and shipped him over with the rest of the First Army and on the fifth day in their training camp in France two British officers with more brass than a church organ between them interrupted gun assembly in his barracks. Who’s the chap here who’s the chemist? the one with more brass asked. When no one volunteered, the one with less brass held his clipboard up and read out, Private First Class Foster? Fos felt the heat rise to his cheeks and took a weak step forward.

—that would be me, sir.

Come with us.

They led Fos past rows of wooden barracks to the quartermaster’s depot into the munition stores. Next to a stepped-temple of stacked diesel drums there was a brick hut with a flat roof, buttressed by sandbags. Inside there were four men in blue smocks and gauze surgical masks in a makeshift laboratory. An astringent tinge of sulfur in the air was the first thing that Fos noticed. Speak any French? the British officer asked before he left him there.

—no sir.

—learn to.

—yes sir.

Four pairs of dark wide eyes stared at Fos above the surgical masks. Then one of the men, the short one in the foreground, spoke. A patch of moisture appeared on his mask from where the words emanated and Fos stared at it, uncomprehending, as if a translation would materialize there as well. The tallest of the four untied his own mask and, with a heavy accent, said, He wants to know are you the candlemaker Uncle Sam has sent?

—candlemaker?

Fos stared at the material around them. There were shelves of chemicals in jars, sieves and grinders, meshes, funnels, fuses of all sorts, crates of French F1 pineapple grenade casings. As best as Fos could reckon from the things that he could recognize, the men in the blue smocks were making firecrackers. The short man gave an impatient shrug and seemed to ask the same question again, only this time with more force so his mask made little jumps, in and out, like a pumping artery. Fos nodded, mutely, and then there were oos and ahs all around and then the short one asked him something else in a nicer way with what appeared to be a little curtsy. He wants to know where in the United States we come from? the tall man translated for Fos.

Oh, Fos answered. North Carolina.

They stared at him.

Kitty Hawk, he said.

—kiti—? the short one repeated.

Kitty Hawk, Fos emphasized. He flapped his arms. The Wright brothers, he said.

There was a burst of recognition as all of them flapped their arms and chimed Or-vee! Wil-bear! That established, everyone turned back to what he had been doing and left Fos in the care of the tallest one among them, the one who spoke the English, a French-Canadian, as it turned out, who handed Fos a mask and smock and began to show him around the little laboratory.

You wouldn’t think it, Fos would later tell his son Lightfoot, but the worst of problems over there was Light, pure and simple. Daylight. ’Cause there wasn’t hardly ever any of it. Almost none. You would have thought the vermin and the brute of noise would have been the worst, but men go crazy without daylight. In the smoke and in the dark. Men go crazy when they have to run out into somethin that might kill them that they can’t see right in front of ’em.

So Fos’s first job in the Great War was to learn from four Frenchmen, who’d had three years’ more experience, how to light the trenches, how to light the field. So that the boys could see what they were shooting at. See death coming, when it came.

Sodium nitrate, Lead tetraoxide, Potassium chlorate, the Canadian recited to Fos from the labels on the bottles on the shelves. Oxidizers, he explained. Hot. Vurry hot, he emphasized. Then he pointed to another group of chemicals and read, Charcoal, Lampblack, Titanium and told Fos, Make the boum. You understand? Fos nodded. All the labels, except the ones for casings and the fuses, were printed in English—all the warnings were, too—and Fos comprehended that all these chemicals must have been delivered from the States, or from England. Somewhere where the native lingo produced disclaimers written in English that warned FLAMMABLE SOLID. SPONTANEOUSLY COMBUSTIBLE. DANGEROUS WHEN WET. The Canadian took down a jar and shook out a salting of powder on a glass slide and said, Paris green. Is copper. Makes the fire burn in blue. Blue flare.

Behind them, one of the Frenchmen nodded over his work and translated, La flambée.

—la fusée, another said.

—la flamme vacillante, and Fos was reminded of a drawing he’d once seen of medieval monks at their tables, brushing color onto pages of gospels, while chanting.

Barium chloride, the Canadian told him. For the green flame. Barium sulphate. All the bariums, green. Sulfur—yellow. For white, pure white flare—the magnesiums. Vurry explosif!

—foum! one of the Frenchmen mimed.

—ker-plouie! another one joked.

But Fos was transfixed by something else. He wasn’t a chemist. He wasn’t transported by processes that needed to burn oxygen. He wasn’t interested in energy that burned. One of the Frenchmen at a small desk at the back of the lab had a glass vial and a paintbrush in his hands and he was painting a sign on a sheet of metal with a liquid that appeared to be water.

But in the dark, Fos knew, that liquid would glow.

—rah-dyoom, the Canadian said.

I know, uttered Fos.

He was impressed.

A gram of radium these days, he reckoned, must cost a fortune. Tens of thousands of dollars.

—caviar, Fos said, searching his English for some way to express to the Frenchman that he knew the stuff’s value.

Above his mask, the Frenchman’s eyebrows went up and he pulled his fingertips together and gestured at his mouth and said, Mais il faut qu’on ne le mange pas!

—he says Don’t eat it, the Canadian said.

—don’t worry! said Fos. He knew about radium, about radium’s effects on humans. Ever since he’d first seen the light that nature can make without burning air, seen his first vision of bioluminescent plankton in the waters off the Outer Banks, Fos had been fascinated by the kinds of lights nature can produce, the ones not always visible to man, the range of lights radiating just off the edge of human vision at the boundaries of the human spectrum. Infrareds and ultraviolets. Colors only birds can see, in their mating rituals, in the feathers of prospective mates. Or colors only underwater animals can see in the ocean’s depth beneath the reach of solar light. x-rays, for example. x-rays fascinated Fos. First time he saw an x-ray image in a magazine when he was still a boy, it captured his attention, totally. He stared at it the way a person stares into an icon during prayer. It was an x-ray of a human leg. You could tell it was a left leg from the way the foot bones were arranged. There was something ghostly in them, Fos thought—in the bones. There was something spectral in the picture. As if the image, in and of itself, possessed a soul. Or captured one. He tore it out and carried it inside his billfold, kept it hidden in his pocket for luck, for prayer, for the same reason someone else would keep a rabbit’s foot. Subsequently, he made a point of reading everything he could about the subject—how x-rays are made, how they’d been discovered, who invented the photographic process of fixing them to film. When he was only twelve he wrote off to one Dr. George Johnson of Boston, President of the American Roentgen Ray Society, to inquire how he could become a member of their august scientific circle. Roentgen, for whom the Society had been named, had “discovered” rays emanating from a cathode-ray tube in 1895, five years after Fos was born. One year after that the Frenchman Becquerel noticed energetic radiation emanating from a uranium salt when they’d fogged a photographic plate that he’d placed next to it by accident. Two years later Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radium—a new element—in uranium ore. The radium, itself, owned the capacity to glow. Soon after the Curies’ discovery, Becquerel went to visit them at their Paris laboratory and asked if he could take a sample of their new element home with him for experiment. They gave him a phial of liquid radium which Becquerel placed in his waistcoat pocket next to his pocket watch. By the time he undressed that night, six hours later, the radium had burned an outline of the phial onto the surface of his skin through three layers of clothing and had irradiated the numbers on his pocket watch so he could read them in the dark. In other words: they glowed.

Soon before he joined up to go to War, Fos had read that a watch factory in Salem, North Carolina, had closed down because a dozen factory workers, watchface painters, had developed a mysterious bone disease, necrosis of the jawbone, and subsequently died. What the article in the local paper hadn’t said was why only the painters at the watch factory had fallen ill. But Fos had guessed the reason. Working on a field that small, painting lines the livelong day on a circle half the size of a silver dollar, the watch painters had a built-in opportunity to attract hazard to their bones, especially if the paint contained pure radium. No doubt for precision and to perfect their points, every quarter hour—maybe even every minute-on-the-minute—the painters must have licked their brushes. So Fos understood the culinary subtleties the Frenchman had referred to when he said, Don’t eat it. Fos was never one for insubordination but the truth was until he saw the radium he’d been thinking he should come clean to the Canadian and tell him to tell the Frenchmen that there’d been a regimental error and they’d recruited the wrong guy. It would have been a stupid thing to do, Fos knew. Even in so short a time as he’d been in France he’d heard the horror stories about what they could expect once they moved into the frontline trenches. At least if he played along here with the Frenchies he might reasonably expect to stay behind the front. When he thought about it he knew he was better off making flares and staying under cover than strapping his gas mask on, arming His Trusty with its bayonet and hurling his entirety against sure desolation, land mines, and the unknown of that hell between the trenches they called No mans land. Still, until he saw the radium Fos wasn’t keen on simply playing out his Army time setting loose a load of chemistry into French heaven. But when he saw the radium he knew at once there was before him something he had dreamed of: Chance of a lifetime. It wasn’t the last time nature’s active miracles would offer Fos A Chance, but they weren’t always as self-evident as that one was. That one was a beaut—the first step in a chain reaction of events that soon had Fos sharing a cramped space dubbed the Boom Bunker in the trenches on the American Line southwest of Verdun outside the town of St. Mihiel with an intense fella from Tennessee they called “Flash” Handy who would ultimately change Fos’s life. Flash was the regimental photographer and he and Fos were the only boys—other than the mustard gas and chlorine boys in the Chem Corps—who were supplied with active chemicals on the front line. Fos had all the oxidizers, neons, burn reducers, phosphorescents, and fluorescents he needed to create a Light at the end of every tunnel for the doughboys in their darkest hours: Flash had the acid baths, developers, gum-bichromates and platinum and silver powders for his photographs. If the Jerries had ever landed a live one on them Flash and Fos had enough volatility in store to take the whole American Expeditionary Force one way to the moon. Fos, himself, took a nasty dose of mustard gas on the September morning the First Army made their raid on St. Mihiel, and after that his eyes watered continuously. He couldn’t see without his specs in daylight, but his night vision stayed the same as it had always been—and it had always been near superhuman. It was legendary, all the things that Fos could see that others couldn’t in the dark. Which meant that not only was he indispensible on night maneuvers in the field but he was also an enlightened wizard in the darkroom—a fact which Flash was quick to grasp. Fos could make a photographic print with such resulting subtle nuance and precision it seemed the image that emerged onto the photographic paper had been bled from Fos’s hands. When the armistice was called on November 11, Flash’s unit was dispatched to Rouen for the Occupation, while Fos’s went to Metz, and the two of them were forced to go their separate ways. But when Fos returned to Kitty Hawk in the late winter of ’19, Flash offered him a partnership in his studio in Knoxville, Tennessee. Fos packed his x-ray books and tide charts into his Army footlocker and drove his old Ford truck away from the Atlantic Coast on the hottest August morning of that year on record. For as long as anyone could remember, Fos’s people had been lightermen in and around the shoals and hoaxing sands of the Outer Banks—conveyancers of cargo in scoop-hulled longboats called lighters in those waters—until the family tree had pruned down to a single shoot, Fos, like a pot-bound exotic in an orangerie too strenuously pollarded. Tidal salts ran in his blood. As he drove away that blistering morning and the land fell off behind him in the first swell of its Continental self, Fos felt a tightness in his chest and his eyes began to water. Well his eyes were always watering, fogging up his glasses. Blister gas, the boys had called the mustard, because that’s what it did. You couldn’t see it coming and it didn’t hit you right away but several hours after it got to you it blistered every living tissue it had touched—in Fos’s case, his corneas and tear ducts. The specs—rimless so he didn’t have to view the world through picture frames—gave his face a bookish absent-minded look, and the fact that he was teary most the time endeared him to old folks and certain kinds of women. But the truth was, for that first year after he was demobilized, that first year in Tennessee, Fos eschewed the company of the gentler sex and stayed almost entirely to himself, either in the darkroom or in his rented place above a bakery, studying about light and working on his theories how to capture it. Fos had several theories that first year. One thing that the War...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- White Sands

- 1. Radiance

- 2. The Glory Hole

- 3. The Curve of Binding Energy (1)

- 4. The Curve of Binding Energy (2)

- 5. The Curve of Binding Energy (3)

- 6. Burning Bridges

- 7. Enter Lightfoot, Radiant

- 8. Paternity

- 9. Maternity

- 10. Fast Fish and Loose Fish

- 11. Fishin

- 12. The Incognito

- 13. The Whiteness of the Whale

- About the Author

- Notes

- Copyright