- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

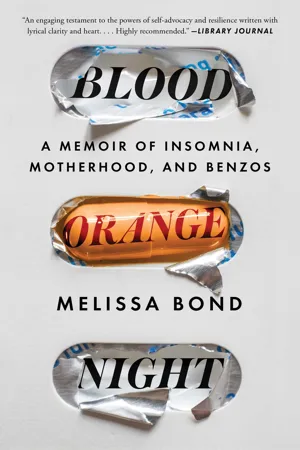

Brain on Fire meets High Achiever in this “page-turner memoir chronicling a woman’s accidental descent into prescription benzodiazepine dependence—and the life-threatening impacts of long-term use—that chills to the bone” (Nylon).

As Melissa Bond raises her infant daughter and a special-needs one-year-old son, she suffers from unbearable insomnia, sleeping an hour or less each night. She loses her job as a journalist (a casualty of the 2008 recession), and her relationship with her husband grows distant. Her doctor casually prescribes benzodiazepines—a family of drugs that includes Xanax, Valium, Klonopin, Ativan—and increases her dosage regularly.

Following her doctor’s orders, Melissa takes the pills night after night until her body begins to shut down. Only when she collapses while holding her daughter does Melissa learn that her doctor—like so many others—has over-prescribed the medication and quitting cold turkey could lead to psychosis or fatal seizures. Benzodiazepine addiction is not well studied, and few experts know how to help Melissa as she begins the months-long process of tapering off the pills without suffering debilitating, potentially deadly consequences.

Each page thrums with the heartbeat of Melissa’s struggle—how many hours has she slept? How many weeks old are her babies? How many milligrams has she taken? Her propulsive writing crescendos to a fever pitch as she fights for her health and her ability to care for her children. “Propulsive, poetic” (Shelf Awareness), and immersive, this “vivid chronicle of suffering” (Kirkus Reviews) and redemption shines a light on the prescription benzodiazepine epidemic as it reaches a crisis point in this country.

As Melissa Bond raises her infant daughter and a special-needs one-year-old son, she suffers from unbearable insomnia, sleeping an hour or less each night. She loses her job as a journalist (a casualty of the 2008 recession), and her relationship with her husband grows distant. Her doctor casually prescribes benzodiazepines—a family of drugs that includes Xanax, Valium, Klonopin, Ativan—and increases her dosage regularly.

Following her doctor’s orders, Melissa takes the pills night after night until her body begins to shut down. Only when she collapses while holding her daughter does Melissa learn that her doctor—like so many others—has over-prescribed the medication and quitting cold turkey could lead to psychosis or fatal seizures. Benzodiazepine addiction is not well studied, and few experts know how to help Melissa as she begins the months-long process of tapering off the pills without suffering debilitating, potentially deadly consequences.

Each page thrums with the heartbeat of Melissa’s struggle—how many hours has she slept? How many weeks old are her babies? How many milligrams has she taken? Her propulsive writing crescendos to a fever pitch as she fights for her health and her ability to care for her children. “Propulsive, poetic” (Shelf Awareness), and immersive, this “vivid chronicle of suffering” (Kirkus Reviews) and redemption shines a light on the prescription benzodiazepine epidemic as it reaches a crisis point in this country.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blood Orange Night by Melissa Bond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE Insomnia

ABC WANTS TO KNOW

November–December 2013

First the light sinks to shadows; then the light is eaten.Have you felt this? Have you been in this room?What does one do with nights when there is no fleshy velvet of sleep?It happened to me, quick as a shot and out of nowhere.I don’t know how many days it’s been since I’ve slept. Two? Four?

IT’S WINTER, AND SNOW IS hunched like odd animals on the trees, when I receive the email from ABC World News with Diane Sawyer. One of the producers found my mama turned benzo withdrawal blogs. I’m amazed I’ve been able to write because of the sickness—the shivering of my eyes in their sockets, the muscles flickering like butterfly wings. Reading becomes impossible until I do the needed thing to beat the symptoms back. But still I write. I must. I don’t need eyes to tap, tap, tap the black squares on the computer keyboard.

Sometimes I think if I can tell the story, I’ll survive. Also, I’m pissed. For me—for others like me slipping into the dark. I try to write with technical and scientific accuracy to modulate my fury. I want people to understand this isn’t anomalous. I cite the medical literature. It’s all there, I say. Just look. There’s a mountain of us who have been buried with this sickness; a continent. I don’t know if this works. All I know is I’ve been writing about this thing that’s happened and now ABC wants to talk to me.

The producer is from New York. Her name is Naria or Narnia and I imagine her with red hair, fiery and ready to dig in. “I found your blogs,” she says. “We want to come to Salt Lake City to interview you.” She asks if I’m willing to tell my story on national television. I pause. Jesus. Diane Sawyer. She’s a legend, a high-ranking news journalist once suspected of being Deep Throat, the informant who leaked information to Bob Woodward in the Watergate scandal. When Diane became the first female correspondent on 60 Minutes, I was in high school. I watched the show every Sunday on the floor of my mother’s bedroom. The TV was stuffed at the end of my mom’s bed and my brother and I had a six-foot swath of carpet on which to deposit ourselves for what we called “tube time.” Watching Diane, I felt a doe-eyed feminist ardor I feel to this day.

My children are asleep downstairs.

My girl is three and my boy is four and I’ve had the sickness since before my girl was born. I don’t know where my husband is, but I know he won’t like it when I tell him they want me to be on national television. My sickness has taken him to the brink. I have no tumor to point to, no lab results over which we can cry together and show friends and family, no known story of what is happening to me. There is only the fire I tell him is in my head. There is the pain and my ribs poking out like railroad ties. He’s tired and the fear has eclipsed him, turning everything between us to shadows. I don’t blame him for this, but the wall between us aches. And now ABC. Now Diane Sawyer.

How can I say no?

When I was young, Diane interviewed Saddam Hussein and the Clintons. She got into North Korea when no one was allowed into North Korea. This woman has heft. She has moxie. Yes, yes, Diane. My God! How can I even hold the fact they want to talk to me without melting into a wild but teary euphoria?

This story’s tricky, and so much news has become a social narcotic. News as candy; news as sensational distraction. And it’s this machine of sensationalism that has me nervous and uncertain in the face of Diane and her producers. I want to tell this Naria or Narnia that I’ll consider being interviewed, but I won’t prostitute my sickness to the media’s love of McNugget news bites.

I’m cynical right now. It’s part of the sickness. Forgive me.

My son makes his “hoo hoo” sound from his crib downstairs. His Down syndrome has made us all more tender than we could imagine. How will being on national television affect my family? How can I protect them? I must ask Narnia why they want to interview me. I will not agree to an interview if I’m to be their prime-time pity sandwich. Because this is so much more than my story. This is the story of millions of people just like me. I just happen to have survived. I just happen to be upright.

I write the producer, terrified.

Yes, I say. I’ll do what I can.

HIS HEART

June–July 2008

IT STARTED FOUR DAYS AGO. Contractions through the night, starting and stopping. There’s a palette of pain—dark, light, hollow blue, heavy blue, liquid red like fire. Sean and I were sure the baby would come easy. We’d prepared. I felt like an Amazonian. We’d taken birthing classes. When labor finally came, I breathed and breathed and first it was ten hours, then twenty, then thirty. Friends came and sang folk songs and played guitars for six hours before giving up and going home. Our doula banged a drum. Call the child out, find the rhythm that will seduce. We drove to the hospital, drove home. There was no sleep. Take black cohosh. Walk from the red rug of the living room to the wild greens growing in the backyard. Finally, at hour forty, we went back to the hospital and I was strapped in, measured, watched on a monitor that had a little stork flying across the screen to represent the baby’s heart—which was failing.

At hour forty-eight, the room filled with a swarm of blue scrubs. I was on a bed with wheels and we rushed down the halls, ob-gyn trotting alongside. I saw the almond dust of hair on his upper lip. Sweat beaded and disappeared. In the room, I was anesthetized; a white whale beached on the shore in this lightblare room. Sean hovered. My boy was cut out. I smelled my flesh burning and then he wailed. His heart has continued to beat—my boy, arrived finally into the world.

And now, four days into our stay at the hospital, I’m drunk with sleep. The nurse opens the door. It’s 2:00 a.m. She’s a dark specter, her body backlit by the fluorescent hall lights.

I lurch up, electric. Something’s wrong. “What is it?” I ask.

“It’s Finch,” she says. “We need to bring him to the neonatal intensive care unit right now. He’s not getting enough oxygen.”

I’m up and stumbling. I shake Sean, who’s been asleep on the bright orange window seat that doubles as a bed. I’m hazy with Percocet, but my body knows something is very wrong.

I’m in my hospital gown with the wolf slippers Sean gave me. We’d thought they were hilarious when he brought them home months ago. They’re huge wolf heads, twice the size of my feet. Clownish. Now they add a surreal element as we jog through the halls.

At the NICU, we scrub frantically using the special bristled brushes. We use a strong antibacterial soap and are directed to scrub up to our elbows. As we try to find the room Finch is in, Sean and I pass several unused incubators along one wall. They’re the size of washing machines.

When we arrive, the nurses are putting a cannula up Finch’s nose to deliver oxygen. Sean and I stand side by side, paralyzed. Finch cries at having the tubes shoved into his little nostrils, and with each howl there’s a corresponding wail in my own body.

Nurse Robin explains that Finch will get oxygen. All his vitals will be monitored with excruciating detail. They’re starting antibiotics right away. “The doctor will give the order, but they’ll likely perform an EKG to check his heart,” she says. We stay for hours, taking turns holding Finch. When we return to my room eight hours later, he’s asleep on the warming slab, his little bird chest barely rising and falling under the thin blanket.

And now, on day five, we will leave and Finch will stay in the NICU. In my room, the nurses begin the process of discharging me. Sean and I sign papers and take the little tote they give us that has pamphlets on breastfeeding and immunizations and a DVD called Don’t Hit, Take Time to Sit, about how to avoid throttling your newborn. After gathering all my things, they tell us to go home and get some sleep.

“Come back at five,” one of the nurses says. “They should have the results from the EKG back by then.”

SEAN AND I conceived Finch less than two weeks after getting married. It was the kind of thing that steals the breath in mid-step. We’d been tangoing a lot post-wedding, as you can imagine, but the ultimate conception tango was just after our visit to Takashi, our favorite Salt Lake City hipster sushi joint. We’d started with the Volcano Roll. After that, we ordered buttery sablefish and the Red Hot Jazz. Waiters came and went, hovering next to our table, not wanting to interrupt. The restaurant evaporated around us. We were giddy with marriage and delicate sablefish and sake. So giddy, we danced a fierce tango in the car just outside Takashi. Then we went home and tangoed in the kitchen. Our steps were slow and breathless and heated, and when we made it to the bedroom, it was only to collapse into a warm marital heap. We were newlyweds and the world shimmered.

Just a few weeks earlier, when we’d discussed my going off birth control, I was sure my being thirty-eight years old would mean months or more before we’d have a taker of any kind. I told Sean that the lady in charge of pulling files in my brain circuitry would have to shuffle way back to get the information on what sperm was and how to use it. “Seriously,” I said, looking as serious as I could, “she’s old. She hasn’t seen this file in decades. It’ll take forever.” This bit of rhetorical strategizing was entirely for my own benefit. Sean had told me two months into our courtship that he wanted kids. Two months. His biological clock was screaming. I, on the other hand, was sure my cosmic alignment would render me infertile at worst, difficult to knock up at best. Either way, I thought we had time. What we had was twelve days, give or take.

Sean and I had been married around three weeks when I got up from the kitchen table in the morning to drive to the grocery store. I didn’t think. I drove. Once there, I bought a pregnancy test. I was being ridiculous—I knew it—but I couldn’t help myself. There was just no way I could be pregnant. I kept saying this to myself while I drove and purchased and ran home to pee on a stick. I told myself this while I looked down at the little blue plus. I told myself I was silly, ridiculous, paranoid, while I peed on the second stick. And then I gawked. I sat in that bathroom for a long time staring at the walls. I’d been the baby of the family. I’d never babysat, never even changed a diaper. Married all of three weeks and I was suddenly, undeniably pregnant.

And though I felt unready, unsuited to motherhood and stunned with the suddenness of creating a human in my body, something happened when I got pregnant. I fell in. Motherhood is like this. Parenthood is like this, but women are given the mama cocktail that drinks us in and we become new creatures. I woke every morning and sat, hands around my cup of tea at our tiny kitchen table in our bungalow. “Take a picture of me,” I’d tell Sean. And when I pulled my shirt up, he’d say, “Still looks like a beer belly,” or “Today you’re a small cantaloupe.” And we’d marvel at how fast my body was changing.

AFTER DRIVING HOME from the hospital, Sean and I fall asleep. We jolt awake just in time to race to the hospital before the shift change at five o’clock. We jump into the car and I tell myself to focus on what’s in front of me. Dashboard. Street signs. That same inane billboard for plastic surgery depicting three breasty melons of increasing size. The sky is the color of chalk, as if all texture has been erased. I feel my heart thumping in my chest. Heart, I think. No, not that—just look at the billboards.

At the NICU, we scrub vigorously. We walk fast, trying not to break into a jog. In room three, Finch is asleep, but the new nurse says we can pick him up if we want. We have to be careful of all the tubing and wires. I’m afraid of pulling something out. I tuck my hands under him and feel the warmth of his bundled body. He’s so tiny, barely five pounds. I hold him against my chest. Sean stands up and walks around the little room. He sits. He looks at me and looks at the floor. We wait.

Finch’s body is the size of half a loaf of Wonder Bread—so tiny, barely there. His hands are little fisted walnuts. I don’t ever want to let go of this body—these eyes, this tiny belly. After ten minutes of holding Finch tight to my chest and pacing the small room, Dr. Templeman walks in. He’s around fifty, with kind brown eyes. He feels nothing like the other doctors we’ve met in the hospital. He wears khakis and a button-down shirt and has the air of a monk. He settles into a chair in front of us and asks how we’re doing. We don’t know how we’re doing, Sean tells him. We want to know about Finch’s heart. We want to know our boy is okay. Dr. Templeman sighs. He looks at Sean and then me before leaning forward and placing his elbows on his knees. “The EKG came back,” he says, “and Finch’s heart is just fine.” He pauses, his kind brown eyes looking into us. I feel air come back into my lungs. “But the blood work has also come back. Finch has tested positive for trisomy 21. He has Down syndrome.”

All sound drains from the room. My throat locks up. My hands go numb against Finch’s little body. Dr. Templeman sits across from Sean and me looking so full of compassion that I can only choke on the tears lodged in my throat. I can’t cry or wail because the torrent of emotions floods me while my brain battles something that feels incomprehensible. I understand completely, but I don’t understand at all. How can our beautiful, perfect Finch have Down syndrome? People with Down syndrome have always been strange to me. The ones I’ve seen always seem to wear Coke bottle glasses. They’re heavy, with wide-set eyes. And they’re retarded. The word suddenly becomes something new to me. Retarded. What does that mean, anyway? Slow? My boy will be slow? My boy may or may not talk? My mind races and slows, trying to find a place to land—something that will help me gain footing.

“How will we know how to take care of him?” I finally ask. And now I’m crying. I’ve never known anyone with Down syndrome. I’ve never even known anyone who’s had a relative with Down syndrome.

At some point a Diane Arbus photo flashes in black and white in my mind. In 1970, Arbus traveled to upstate New York to photograph the people who lived in institutions for the mentally retarded. There were a lot of these institutions back then—warehouses where people who were deemed damaged or mentally deficient could be put away so as not to be a burden on family or society. In the photo that surfaces from my memory, a group of four or five adults stand at a distance, holding hands in a field. It’s Halloween, so a few of them are wearing clown masks and sheets that billow around their exposed, pudgy legs. And there’s something about the way they hold on to one another’s hands—as if they’re the only hands they have to hold on to in the world—that makes the scene bleak and horribly lonely. But this picture makes no sense to me as I look at my beautiful boy. I’ve never imagined the people in the photos as having parents. I’ve never considered what it must have been like for those parents to have been told their child was deficient or imperfect in any way. What was it like for them? What was it like for the children who got sent away? The thought brings a fresh choke of tears. I try to keep myself together but I’m falling apart piece by piece in this tiny glass-walled room.

After answering our questions about physical and occupational therapies, Dr. Templeman leaves. I sit holding Finch. I look into his unwavering blue eyes and try to connect my idea of Down syndrome to his perfect little body. And in the space of a moment, all the mental pictures I’ve had of those people in institutions who looked so lonely and sad and different fall away. The only thing that has oxygen to breathe is the love I have for my boy. The anguish of those pictures evaporates in the love that feels like it’s breathing me. In and out, in and out....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Preface

- Part One: Insomnia

- Part Two: The Book of Sleep

- Part Three: Dr. Amazing

- Part Four: Great Balls of Fire

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright