- 315 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

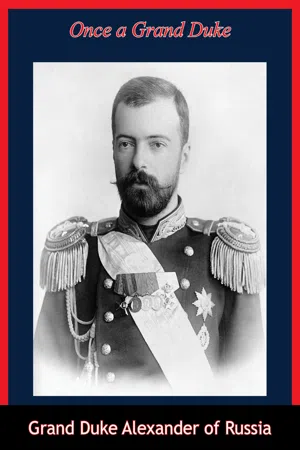

Once a Grand Duke

About this book

Alexander lived in Paris when he wrote his memoirs, Once a Grand Duke, which were first published in 1932. It is a rich source of dynastical and court life in Imperial Russia's last half century, and Alexander also describes time spent as guest of the future Abyssinian Emperor Ras Tafari."The history of the last fifty turbulent years of the Russian Empire provides only a background, but is not the subject of this book."In compiling this record of a grand duke's progress I relied on memory only, all my letters, diaries and other documents having been partly burned by me and partly confiscated by the revolutionaries during the years of 1917 and 1918 in the Crimea."—Alexander, Grand Duke of Russia, Foreword

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Once a Grand Duke by Grand Duke Alexander of Russia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Baltic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONCE A GRAND DUKE

CHAPTER ONE — OUR FRIENDS OF DECEMBER THE FOURTEENTH

A TALL man of military bearing crossed the rain-drenched courtyard of the Imperial Palace in Taganrog and rapidly made for the street.

The sentinel jumped to attention, but the stranger ignored the salute. The next moment he disappeared in the dark November night that had wrapped this small southern seaport in a thick blanket of yellowish fog.

“Who was it?” asked the sleepy corporal of the guard, returning from his tour around the block.

“I think,” answered the sentinel hesitatingly, “that it was His Imperial Majesty going for an early stroll.”

“Are you mad, man? Don’t you know that His Imperial Majesty is gravely ill? The doctors gave up hope last evening and expect the end will come before dawn.”

“It may be so,” said the sentinel, “but no other man has those stooping shoulders. I guess I ought to know, having seen him daily for the last three months.”

A few hours later a heavy knell filled the air for miles around, announcing that His Imperial Majesty, the Czar of all the Russias and the conqueror of Napoleon—Alexander I—had passed away in peace.

Several special couriers were dispatched immediately to notify the Government in St. Petersburg and the Heir Apparent, the brother of the late Czar, Grand Duke Constantin in Warsaw. Then a trusted officer was called in and ordered to accompany the imperial remains to the capital.

For the following ten days the entire nation breathlessly watched a pale, worn-out man crouching behind a sealed coffin and driving in a funeral coach at a speed suggestive of a raid by the French cavalry. The veterans of Austerlitz, Leipzig and Paris, stationed along the long route, shook their heads dubiously and said that it was a strange climax indeed for a reign of unsurpassed glamour and glory.

“The late sovereign is not to be laid in state,” said the laconic statement issued by the Government on receipt of the dispatches from Taganrog.

In vain did the foreign ambassadors and powerful courtiers try to find a plausible explanation for this mystery. Everybody pleaded ignorance and expressed bewilderment.

In the meantime something else happened which caused all eyes to be turned from the imperial mausoleum in the direction of the Plaza of the Senate. Grand Duke Constantin had abdicated in favor of his brother Nicholas. Happily married to a Polish commoner, he felt reluctant to exchange his carefree existence in Warsaw for the vicissitudes of the throne. He asked to be excused, and hoped his decision would be respected.

His letter had been read by the puzzled Senate in an atmosphere of gloomy silence.

Grand Duke Nicholas—his name sounded but vaguely familiar. Of course there were four sons in the family of Czar Paul I, but who could have expected that the handsome Alexander would die without issue, and that the robust Constantin would spring such a surprise on his beloved Russia? Several years younger than his brothers, the Grand Duke Nicholas followed until December, 1825, the well-established routine of a man following a military career, and the Minister of War seemed the only official in St. Petersburg to have formed an idea of the new Czar’s habits and talents.

An excellent officer, a dependable executor of orders, a patient solicitor who had spent many hours of his youth waiting in the antechambers of high commanders. A likable chap of sterling qualities, but a poor boy who knew nothing of the complicated affairs of state, for he had never been invited by his brother to participate in the deliberations of the Imperial Council. Fortunately for the future of the empire, he would have to rely upon the judgment of statesmen, experienced and patriotic. This last thought brought a certain comfort into the hearts of the ministers as they went to meet the youthful ruler of Russia.

A certain coolness marked their encounter. First of all, declared the new Czar, he wanted to see with his own eyes the letter of Grand Duke Constantin. One had to be prepared for all sorts of intrigues when dealing with persons who did not belong to the army. He read it carefully and examined the signature. It still seemed unbelievable to him that an heir apparent to the Russian throne should disobey the command of the Almighty. In any event, brother Constantin should have advised the late Czar of his plans in due time, so that he, Nicholas, could have been afforded a possibility of learning le métier d’un Empereur (the profession of an Emperor).

He clenched his fists and got up. Tall, handsome and athletically built, he looked a perfect specimen of manhood.

“We shall carry out the orders of our late brother and the wishes of Grand Duke Constantin,” he concluded curtly, and his usage of the plural did not escape the ministers. This young man talked like a czar. It remained to be proved whether he was capable of acting as one. The occasion presented itself sooner than expected.

Next day December 14, 1825—having been set for the army to take its oath of allegiance to the new Czar, a secret political society headed by young men of noble birth decided to seize this opportunity for an open revolt against the dynasty.

It is very difficult, even after the passing of a century, to form a definite opinion of the program of those who were to be known as “the Men of December” (Dekabristy). Officers of the Guard, gentlemen-philosophers and writers, they decided to work together not because of the similarity of their ambitions, but because of that feeling of self-identification with the oppressed which had been released by the French Revolution and was common to all of them. No semblance of an agreement ever entered their discussions as to what should be done on the day after the fall of the existing régime. Colonel Pestel, Prince Troubetzkoi, Prince Volkonsky and other moderate leaders of the St. Petersburg branch of the society dreamed of building the state along the lines of the constitutional monarchy adopted by England. Mouravieff and the theoreticians of the provincial branches clamored for a Robespierrian republic. With a possible exception of Pestel, a sad man of mathematical mind who undertook the trouble of working out a detailed project of the Russian constitution, the rank and file of the organization preferred to center their imaginations on the spectacular side of their attempt. The poet Rylyeff saw himself in the part of Camille Desmoulins, haranguing the crowds and proclaiming freedom. A poor unbalanced youth by the name of Kakhovsky preached the necessity of imitating “the noble example of Brutus.”

Among the numerous young followers attracted by the names of the scions of Russia’s best families were Kukhelbecker and Pouschchin, two school chums of the famous poet Poushkin. The latter, advised of the approaching events, left his country place and started for St. Petersburg, when a frightened hare crossed the road in front of his carriage. The superstitious poet stopped the driver and turned back.

In any event, such was the story told by him to his friends the conspirators, but he did write a beautiful poem dedicated to their daring undertaking.

Although the secret society was formed as far back as 1821, its activities had never gone beyond the heated meetings that took place in the apartments of Pestel, Rylyeff and Bestujeff-Rumin. Considering the well-known Russian ability to engage in endless debates, chances are they would have talked themselves out of the whole idea of doing anything at all, had it not been for the powerful impetus provided by the mysterious death of Alexander I and the abdication of Grand Duke Constantin.

“Now or never,” said Kakhovsky, waving his enormous pistol. Colonel Pestel hesitated, but the majority seconded the fiery tribune.

On the evening of December 13, having failed to reach a unanimous decision, they left for the military barracks and spent the night in conversations with the soldiers of the St. Petersburg garrison.

The plan, if any, consisted in leading out several regiments to the Plaza of the Senate and forcing the Emperor to agree to certain amendments to the constitution. Long before dawn it became clear that the attempt had failed. Notwithstanding the fine eloquence of the aristocratic orators and the lengthy quotations from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the soldiers remained noncommittal. The only question asked by them had to do with the meaning of the word “constitution.” Could it be the wife of Grand Duke Constantin the gentlemen were referring to?

“It is time yet,” suggested Pestel, “to call everything off.”

“Too late,” answered his associates. “The Government is already notified of what is going on. We are bound to be arrested and tried. Let us die fighting.”

Finally a few battalions commanded by the popular officers belonging to the secret society agreed to march. Their progress through the streets toward the Plaza of the Senate encountered no resistance. The military governor of St. Petersburg, General Miloradovich, one of the surviving heroes of 1812, who bowed to no one in his passion for the dramatization of historical events, placed a regiment of loyal cavalry and a battery of artillery at the foot of the Senate Building, but permitted the plotters to reach their destination without interference.

All morning long a heavy fog had been creeping up from the banks of the Neva. When it lifted toward noon, the shivering crowds of curious spectators beheld the two opposing armies standing in front of each other, divided by some three hundred feet of no man’s land.

Minutes, hours, went by. The soldiers commenced to complain of hunger. The leaders of the secret society felt helpless and miserable. They were willing to sacrifice their lives, but the Government did not seem inclined to start hostilities, and it would have been sheer madness on their part to attempt sending the infantry against the combined forces of cavalry and artillery.

“It’s a standing revolution,” said a voice from behind, and an outburst of laughter greeted this historical phrase.

Suddenly a hush fell over the crowds.

“The young Czar, the young Czar! Look at him riding next to Miloradovich.”

Disregarding all advisers, who pointed out that he had no right to risk his life, Emperor Nicholas I decided to assume personal charge of the situation. At the head of a group of officers, mounted on a tall horse, he presented an easy target for the revolutionaries. Even a mediocre shot could hardly have missed him.

“Your Imperial Majesty,” pleaded the frightened Miloradovich, “I beg of you to return to the palace.”

“I will stay right here,” came the firm answer. “Someone must save the lives of these poor misguided people.”

Miloradovich spurred his famous white mount and galloped toward the opposite end of the Plaza. Not unlike his master, he had no fear of the Russian soldiers. They would never dare fire at a man who had led them against the Old Guard of Napoleon.

Stopping in front of the revolutionaries, Miloradovich made one of those colorful speeches that had inspired many a regiment during the battles of 1812. Every word went home. They smiled at his jokes. They brightened up at the familiar allusions. One minute more, and they would have followed his “brotherly advice of an old soldier” and started back for the barracks.

Just then a dark figure appeared between them and Miloradovich.

Pale, disheveled, smelling of brandy, and having never parted with his pistol since early morning, Kakhovsky fired point-blank: the resplendent general sank back in the saddle.

A riot of indignant vociferations broke loose on both sides.

The Emperor bit his lip and glanced in the direction of the battery. The echo repeated the bark of the guns all over the city.

The standing revolution had come to an end. Several score of soldiers were killed, and every one of the leaders was arrested by midnight.

“I shall never forget my friends of December the fourteenth,” said the Emperor weeks later, and signed the sentences condemning Pestel, Kakhovsky, Bestujeff-Rumin, Rylyeff and Mouravieff to the gallows, and the rest of their associates to penal servitude in Siberia.

He never did. During one of his journeys through Siberia he inquired into the minutest details of the lives of the exiled aristocrats who had unwittingly become the predecessors of a movement which was to achieve its goal ninety-two years later.

He had likewise expressed the desire to talk to a hermit known as Feodor Kousmich, and had made a long detour in order to visit his humble log cabin in the wilderness. There was no witness to their meeting, but the Emperor remained closeted with the saintly man for over three hours. He came out in a pensive mood. The aides-de-camp thought they had noticed tears in his eyes. “After all,” wrote one of them, “there may be something to the legend which tells us that a simple soldier had been buried in the imperial mausoleum in St. Petersburg, and that Emperor Alexander I is hiding in the guise of this strange man.”

My late brother, Grand Duke Nicholas Michailovich, spent several years working in the archives of our family, trying to find a corroboration of this astounding legend. He believed in its emotional plausibility, but the diaries of our grandfather Emperor Nicholas I, strangely enough, failed to mention even th...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- CHAPTER ONE - OUR FRIENDS OF DECEMBER THE FOURTEENTH

- CHAPTER TWO - A GRAND DUKE IS BORN

- CHAPTER THREE - MY FIRST WAR

- CHAPTER FOUR - AN EMPEROR IN LOVE

- CHAPTER FIVE - THE WINDLESS AFTERNOONS

- CHAPTER SIX - A GRAND DUKE COMES OF AGE

- CHAPTER SEVEN - A GRAND DUKE AT LARGE

- CHAPTER EIGHT - A GRAND DUKE SETTLES DOWN

- CHAPTER NINE - MY RELATIVES

- CHAPTER TEN - MILLIONS THAT WERE

- CHAPTER ELEVEN - NICHOLAS II

- CHAPTER TWELVE - TIN GODS

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN - DRIFTING

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN - NINETEEN HUNDRED FIVE

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN - HE REBOUND

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN - THE EYE

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN - ARMAGEDDON

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN - ESCAPE

- CHAPTER NINETEEN - THE AFTERMATH

- CHAPTER TWENTY - THE RELIGION OF LOVE

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER