- 245 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

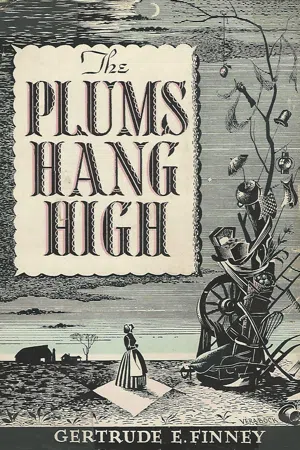

The Plums Hang High

About this book

A young English couple sail to the new land where fortunes like plums are for the taking. But nothing has prepared Hannah Maria, who trusts in the comforts of her brother's home, for the crude life of a Midwest farm in 1868. Only a deep love and her proud spirit sustain her in early bitterness and despair.

Jethro, with no experience on the land, wants to be a farmer. A kindly, hardworking couple take the tyros to their hearts. Some lessons are bitter, some laughable, as they become farmer folk. Their first farm turns out to be worthless and they must hire out again on shares. Tender and poignant is the tale of the dress washed out each night, of the two who ran away to see the circus and sold the family's valuable horse. In a great blizzard Jethro goes for nurse and doctor, returns to find a baby has been born without their help. At last Jethro is famous for his Clydesdales.

They have an assured position and honors come.

The Plums Hang High has a sense of the drama of life itself, of generation succeeding generation.

Jethro, with no experience on the land, wants to be a farmer. A kindly, hardworking couple take the tyros to their hearts. Some lessons are bitter, some laughable, as they become farmer folk. Their first farm turns out to be worthless and they must hire out again on shares. Tender and poignant is the tale of the dress washed out each night, of the two who ran away to see the circus and sold the family's valuable horse. In a great blizzard Jethro goes for nurse and doctor, returns to find a baby has been born without their help. At last Jethro is famous for his Clydesdales.

They have an assured position and honors come.

The Plums Hang High has a sense of the drama of life itself, of generation succeeding generation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THERE WAS MUCH LAUGHTER BUT LITTLE MERRIMENT IN THE old house in England that night. Staglands once again had gathered beneath its venerable roof what was left of the flock it had produced, nurtured and prodded into adulthood. Tonight they had assembled to bid Godspeed to the fourth of their number to leave for America.

Elizabeth Castlereagh, the mother, in her chair by the briskly leaping flames in the great stone fireplace sat with shawl-covered feet on their hassock: the only concession to age she allowed herself. Tall, handsome, not quite austere, hex dignity was unassailable. Her capable hands, lying in her lap, were veined, but any smoothness glycerine and rose water could preserve remained fragrantly upon them. Her hair had turned but little gray and was habitually worn close to the head in careful high arrangement. Frequently it had been said that her eyes were the color of the inside of a wild violet.

Close to her hassock stood James Castlereagh, the father. Round, and barely as tall as his wife, he always maintained there was more to him than to her, only he preferred to keep his weight close to the good earth.

Elizabeth looked up at him now. By nature more given to jollity and high spirits than his wife, he now was pathetically without them. Occasionally he shook his head forlornly as though in negation, or protest, to his thoughts. Giving up the child of his old age to America, which had claimed too many of them already, was almost more than he could bear.

In pity Elizabeth turned to the four daughters who stood together at the table under the high mullioned windows. By day these windows flooded the room with east light. Tonight, they were brooding and dark and cold.

“Ring for Jenks to draw the curtains,” Elizabeth called gently, “and come closer.”

Eliza pulled the cord and old Jenks came, limping with rheumatism. The swinging red-velvet folds were warmer than the night.

In a soft swishing of taffeta and crinoline, the four women left the package they had been examining on the table. Eliza and Esther were tall like their mother but lacked her grace. Betty and Jemima were shorter and leaned toward obesity like their father. At their approach, their father eyed them somberly. Elizabeth put out her hand to them. “It is a time to draw close.”

She watched them as they drew up their chairs, these good, almost elderly, women who were her daughters. Noting their advancing age was ever a shock to her.

“When Hannah Maria comes down,” she said, “remember to be merry. She is putting on a performance of bravery...But she is frightened. Having to catch that miserable train before dawn isn’t helping...”

“Heavens, no!” Jemima, closest sister to Hannah Maria in age, but still fifteen years older, spoke with unusual agitation. “Just the thought of going to America gives me a chill. Starting in the fairest sunlight, or the deepest night, would yet be the end of the world to me. If my husband should say...”

“Yes,” interrupted Eliza, the oldest sister, “if your husband should say, ‘Come, we are going to America,’ you would weep, but you would go, Hannah Maria isn’t weeping but she is going.”

“Hush, not so loud! She will be down any minute.”

“Sh-h-h, Jethro will hear!”

The four sisters turned to glance down the room where their husbands stood, laughing and talking, grouped around Jethro Howard. From that young man of them all this night, confidence and enthusiasm emanated in waves of energy. Dawn could not come too soon for him; his whole manner proclaimed it.

“What possesses Jethro?” Eliza protested. “He is usually level-headed. And he was beginning to do well in business...”

Their father turned to answer Eliza. “He’s going back to the land and he wants plenty of space to do it in.” With his horses and seeds and lands, James Castlereagh understood this move better than any of them. It was only that the loss of his daughter, who had turned to him since toddling days more than to her mother, was like bereavement. “Aye, business, to some, is not the aim and end of existence,” he added, glancing significantly at these daughters whose husbands to a man were engaged in business in London. And who was to take over his farms when he no longer was able? The matter gave him grave concern, his only two sons gone to America as they were. One already dead there.

“But America!” exclaimed Jemima. “It’s a land of no return. It has taken three of us already. Stephen and James. And Ann.” Ann, their oldest sister, had been most beautiful of them all. Jemima lowered her voice, as they all did when they spoke of their sister Ann. “How can Jethro take Hannah Maria to America! It is certain death. Always fighting, first with England, continually with the Indians, and now, only just finished, among themselves, North against South. What will it be next?”

Jethro’s vibrant young voice rose for a moment above the others. “So I say, if you want to make a fortune, go where fortunes are made.”

A burst of half-reluctant laughter rose from the group at the end of the room. The sisters waited impatiently until the rumbling male conversation had been resumed, then Eliza, oldest of them now, spoke, her glance still upon the men.

“I suppose there isn’t a man among them who is not secretly envying Jethro his courage in going to America. A man feels no compunction in breaking up a family.

“But of all people, Hannah Maria to go to America! Why, she is no more capable of managing a household than a kitten. And her baby! Her Jeffie, Mother, is your baby. And you know it. Yours and Laurice’s.” Her tone implied that her own children had had no French nurses. “Aside from the actual physical functions she knows absolutely nothing of the baby. Or his needs. In fact, she doesn’t know he has needs, excepting that he becomes hungry too often.”

Elizabeth, without answer, gazed into the fire. Her conscience accused her unbearably. It was the tragic heritage of English mothers to lose their children: to Africa, to Australia, India; New Zealand, Canada, the United States. As soon as they were old enough, boys especially, so many of them went. Four of her eight! It was a high percentage. This common urge had taken Stephen, only seventeen, and now he was dead somewhere in America...But Ann and James! In a swift gesture her hand rose to cover her eyes.

Out of the silence, Betty spoke, Betty, the manager. “Can’t someone stop this? Father, can’t you get Jethro’s parents to intercede? The Vicar should have some influence over his son.”

James Castlereagh looked down at his daughter. There was no cheer in his eyes. “They have been to the vicarage, Jethro and Hannah Maria, to say good-by.”

“What did he say?”

“Aye! It was restraining and all that! He said, ‘Go with my blessing, son. It’s what I would have done had I been able when I was young.’ Helpful! Ha!”

Betty moaned. “But Jethro has never farmed a foot of ground. How does he expect to make a success of farming? He has been in college and then in his haberdashery all his adult years. Selling neckties and coats and hats—how has that been any preparation for farming?”

Her father, though opposed to this move as much as anyone, felt constrained in honesty to present Jethro’s cause as far as he knew it. “Aye, the haberdashery shop was only a means to an end for Jethro. It takes capital to cross an ocean and to buy a bit’ land. And capital Jethro did not have. Sons of vicars are not noted for possessing well-lined pockets. Aye. But why cross an ocean? He could farm in England. I’ve made him every sort of offer—short of giving him the farms outright—to induce him to come in with me. But he’s an obdurate lad. From the conversations I’ve held with him, I’m beginning to think—aye, I’m beginning to think there’s something more than meets the eye here...”

“No!” Betty and Jemima exclaimed together. “No! Not like Ann...”

Their father shook his head, thoughtfully.

Elizabeth Castlereagh continued to sit, silent, her tired eyes watching the fire. Her heart was cold with dread, and words choked in her throat.

* * * * *

ALONG the hall upstairs came Hannah Maria. She could not wait longer to appear. She had been in her room almost an hour while the family waited downstairs.

Inside her gray-silk basque her heart pumped icy fear. Tomorrow! Tomorrow was such little time. The whole terrifying situation rose before her like an advancing tidal wave. She put up her hands to fend it off.

“No!” She had spoken aloud.

Quickly she glanced about. The privacy of the candle lighted stairs and the hall below had not betrayed her. “No! I can’t! I won’t!” She stood on the top step and spoke down into the silence. “I will not!”

Hannah Maria’s “No” to parents and doting sisters had almost always cleared away any state of affairs which annoyed her. She had made good use of it. Then she had seen that such open tactics did not endear her to friend or stranger. To sisters, even, but with growing wisdom she had tempered demeanor to circumstance. Under the strict tutelage of the Misses Speke-Ridley at Wellington Seminary for Young Ladies, she had dropped such abrupt attack altogether when abroad from home. She had never used it with Jethro Howard. From the moment she had seen him, his presence had quietly melted any mounting burst of rebellion. Even after two years of marriage to him, he still possessed that power.

But now, she wanted to say, “No! No! No!” She wanted to stamp her feet. She wanted to scream, “No! I won’t! I will not do this thing!”

But she knew she would! Jethro was going to America, That raw terrible country. That horrible continent of disgrace and heartbreak and awful death. Her brother Stephen, only a boy, was there somewhere in a lonely grave. And beautiful Ann, swallowed up and dead! Her sister had better have stayed at home and faced the disgrace than to have gone out to that wilderness to die of a broken heart, with only a dissolute husband to watch her out of wretched life.

And now Jethro was going. With sickening conviction she said, “And I’m going tool I am doing this dreadful thing to the baby. I am going to take Jeffie to a land of cutthroats, and worse! Oh, no! How could I!”

She took another step. Her full skirts cascaded like gray foam behind her. Her hand slipped along the century-old rail, her footfall lost in the deep pile of the stair rug.

A burst of laughter floated to her from the library. She moved toward it. Her feet dragged over the Chinese rugs on the stone-floored hall. Absently, she paused before the mahogany mirror, habit stronger than thought. The candles in their iron sconces flickered. The glass gave back an unsteady reflection of frightened violet-blue eyes in oval face, brown curls caught at the crown and allowed to spill where they would.

But she did not see shining curls. She saw a ship. On it, her Jethro, alone. He was standing in the bow. He was looking expectantly out over the sea. Out ahead to America!

On the ship then she saw her Jethro, and herself, and little Jeffie. The wind was cold. And little Jeffie in all his six weeks of life had never been cold. He had never been out of the warm flannel and lavender of the nursery. The old rosewood cradle upstairs...Jethro must be mad! I will not go!

But there was James...

Suddenly she left the mirror, and lifting her skirts, she ran back upstairs. She hurried along past her mother’s door, past the nursery, past her own door. She stopped at a table farther along the hall. There in the familiar darkness she felt for the candle which stood in its silver holder with the matches and the snuffer close by. Hastily, she struck the match and lighted the candle. Holding it high, she went to stand before a full-length painting. The merry face of her brother James came out of the gloom, breathtakingly warm and living in the flickering light.

His violet-blue eyes looked down at her benignly, his mouth was smiling. A dashing fellow! She looked up at him. He had gone with his servant-girl wife to America before she could remember. But she had always loved him as she saw him in the picture. She had need of him now. She leaned closer. She lifted the candle higher and peered out beneath it.

“Oh, James, we’re coming,” she whispered. Did she see a twinkle in an eye?

She stood still, wondering if she should have written James. But, no. What could she have said? She caught his eye again, and directed her thoughts to this pictured brother as she had done since childhood. No. You will know about it then. We will need only a nursery for Jeffie and his nurse and a sitting room and bedroom for Jethro and me. You will have room and to spare.

The lively eyes above her were full of understanding, inviting and interested. She could almost see him nod. She looked questioningly at the painted face. There was so much she wanted to ask and no one she knew could answer. Going to America was like dying. People went there, as had ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Plums Hang High by Gertrude E. Finney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.