- 179 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

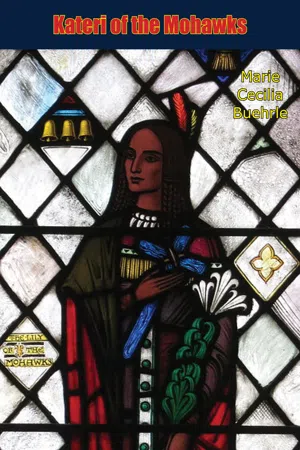

Kateri of the Mohawks

About this book

FROM SAVAGE TO SAINT

First published in 1954, this book tells the story of a Mohawk chieftain's daughter who may soon may be canonized as North America's first native saint.

THE daughter of a Mohawk chieftain, Kateri Tekakwitha was born in 1656. Her mother, an Algonquin Christian captured in a Mohawk raid, was the brief but enduring influence in Tekakwitha's life. Whatever chance she may have had to teach her child about Christianity was lost when both parents died in a smallpox epidemic.

Tekakwitha was ten years old when she heard for the first time of Rawenniio, the white man's God. But a full ten years passed before a Blackrobe, the Jesuit Father James de Lamberville, baptized her on Easter Sunday, 1676.

She practiced her new faith with ever increasing fervor. After fleeing to the mission settlement in Canada, where she could join other Christians in the undisturbed practice of their faith, she performed extreme penances.

Through a close companion, Kateri's words have been preserved for us, revealing the spirit of love and atonement with which she entered into this voluntary mortification. Soon her spent body could no longer contain her soaring soul. She died at the age of twenty-four, leaving all near her convinced that they were witnessing the passing of a saint.

First published in 1954, this book tells the story of a Mohawk chieftain's daughter who may soon may be canonized as North America's first native saint.

THE daughter of a Mohawk chieftain, Kateri Tekakwitha was born in 1656. Her mother, an Algonquin Christian captured in a Mohawk raid, was the brief but enduring influence in Tekakwitha's life. Whatever chance she may have had to teach her child about Christianity was lost when both parents died in a smallpox epidemic.

Tekakwitha was ten years old when she heard for the first time of Rawenniio, the white man's God. But a full ten years passed before a Blackrobe, the Jesuit Father James de Lamberville, baptized her on Easter Sunday, 1676.

She practiced her new faith with ever increasing fervor. After fleeing to the mission settlement in Canada, where she could join other Christians in the undisturbed practice of their faith, she performed extreme penances.

Through a close companion, Kateri's words have been preserved for us, revealing the spirit of love and atonement with which she entered into this voluntary mortification. Soon her spent body could no longer contain her soaring soul. She died at the age of twenty-four, leaving all near her convinced that they were witnessing the passing of a saint.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kateri of the Mohawks by Marie Cecilia Buehrle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

ReligionChapter 1

Darkness lay heavily over the Valley of the Mohawks while the faint, swift dipping of paddles barely broke the stillness of the hour preceding the dawn. When the slow October light crept over the hills into the adjacent forest the sound ceased. A bird stirred in the thicket, a canoe slipped into concealment under the weeds, and the howl of a dog echoed over an empty river.

Along the trail winding like a tattered ribbon through the trees, three figures moved in single file. A Mohawk led the way, his head thrust forward, the scent of danger in his nostrils. From time to time his hands were outstretched, clearing the way, sheltering the girl behind him from the whip of a branch. Her step, light upon the fallen leaves, was swift as his. Her eyes were distended with fear and a tremor shook her at the slightest sound, the unexpected beat of a wing, the tap of a woodpecker, an uneasy shifting among the leaves. Behind her a Huron walked with slower pace, turning every few moments to watch for the approach of some terror from the rear.

Suddenly, something tore at the silence. The girl smothered a cry. The Mohawk stopped short, with fingers quick upon his musket; but he fired no shot. The Huron leaped up from behind. It was nothing but the whirr of a startled grouse.

No one spoke. The Mohawk’s lips were drawn into a thinner line as the three fell into step again. The girl kept pace with the gathering speed. The brown shawl had dropped from her head and lay loosely about her shoulders; but she clutched it tightly at her throat. The path narrowed through the crowding trees. The Mohawk turned, his finger upon his lips.

“Kateri,” he whispered, “stay close to Jacques. I must fall behind.” Her eyes smiled in reply; but her lips did not move. He looked at the Huron, tapped his musket, and the Huron understood.

Not many miles away, at the Dutch trading post, Iowerano, the Turtle chief, rose abruptly, upsetting his mug of firewater, leaving his neighbors from Andagoron, the castle of the Bears, sitting at the table, staring and speechless. The conversation had become infuriating. For some time the mere mention of the Praying Castle on the St. Lawrence had been enough to put him into a rage, and now rumors were circulating in every corner of the Dutch town, that during his absence from the Turtle village of Gandawagué, the Oneida chief, the famous Hot Powder had come down from Canada with two other Christian Indians, and was speaking to the people. More and more these fanatics from the Praying Castle were luring the Christian Mohawks to Sault St. Louis. He shook his fist toward the north and without a word of explanation flung himself out of the low Dutch door, nearly colliding with Fleetfoot, the swiftest messenger of Gandawagué.

Chief Iowerano scowled. “Tell it quickly,” he commanded before the other had a chance to speak. “Have the French come?”

“Tekakwitha,” panted the messenger. “Tekakwitha has gone.”

“Gone where?” roared the chief. “With whom?”

“No one knows. She is not in the long house. Hot Powder left yesterday for the castle of the Oneidas. This morning the Mohawk from the Sault and his companion, a Huron from Lorette, were missing.”

Iowerano did not wait to hear more. “Tekakwitha has run away to Canada,” he muttered to himself, suspicion giving way to a raging fear. In a hurry he provided himself with three bullets. “To kill,” he growled as he picked up his musket and rushed from the trading post.

Shrewdly he estimated that the fugitives must have taken to the woods when they reached the sharp curve not far from the spot where Chuctamunda Creek tumbles downhill into the river. The forest was still as though stripped of every living thing. Not even a noiseless squirrel was scampering up a tree trunk. The leaves lay lightly scattered upon the ground as though no human foot had passed over them.

The trail curved. At last! Something was moving toward him. An Indian, but alone! Torn by the storm within him, Iowerano had not seen the Mohawk hesitate for a moment and then advance, knowing that it was too late to turn back without being discovered. He noticed only a nonchalant figure loitering along the way and looking about him; a hunter obviously, in search of game. Iowerano was not interested. He could not see the face of Onas and fury had dulled his usually keen perceptions. The man was standing still now, his back turned, looking up into a tree. The chief saw him point his gun and fire into the depths of the forest. Yes, a hunter....Iowerano fingered his own musket and staggered on.

Kateri heard the shot, shivered, and wrapped herself more closely into the folds of her shawl. The Huron heard; and they ran, swiftly, silently, like the hunted things of the forest seeking shelter. Breathlessly they reached a shallow ravine. There, under a ledge of rock he concealed her. She covered herself with her brown shawl, the color of the earth, and he strewed dead leaves over her. Carelessly he threw himself down in a clear space nearby, lit his pipe and waited.

The chief was beginning to tire. Rage, driving him on remorselessly, had lashed the life out of him. There was nothing here to capture, nothing to kill. Surely not this other Indian relaxed upon the ground, puffing at his pipe, blowing smoke rings into the quiet air. The very sight of him made the chief ridiculous. The first violence of his fury had spent itself. Perhaps he would find Tekakwitha at home when he got there. She may have been in the fields, at the well, anywhere. In the village by this time they may be laughing at him. He was foiled and humiliated. This lazy fellow did not so much as turn his head to look at him.

From the adjoining ravine there was no sound. The girl had heard a muttering that she knew. Her eyes were closed and all was dark. She breathed so quietly that not a leaf upon her stirred. For a moment the chief stood still, scowling upon the landscape, irritated by its peace. His eyes narrowed and he flung an angry glance at the Huron, who he believed was probably one of the captives adopted by the Iroquois.

“Have you seen the girl Tekakwitha? Did anyone pass this way?” he panted.

The Huron shook his head. “Tekakwitha?” he asked, staring stupidly at the chief.

“Imbecile!” roared Iowerano, turning back in disgust. Then he spat, and with a growl in his throat turned back in the direction from which he had come.

Like the dropping of a mask, apathy vanished from the face of the Huron and life shot back into his eyes; but he did not shift his position until the receding figure had disappeared far into the charged silence. Then he sounded the note of the quail. There was no answer. “Kateri,” he whispered, leaping down into the ravine. She was motionless upon her knees. Her clasped hands trembled; but the tenseness and the terror had gone out of her eyes and their quiet depths glowed with a new and steady light.

Onas the Mohawk had lost no time. Nearer and nearer came his call, the call of the owl. All was well. Without a word they fell into line as before. On they pressed through the trees toward the Lake of the Blessed Sacrament that Isaac Jogues had named.

Chapter 2

It was the year 1656 in the village of Ossernenon on the south bank of the Mohawk River. In Chief Kenhoronkwa’s lodge, Kahenta, the Algonquin wife, looked long and lovingly into the face of her sleeping papoose. At dawn when it was born, the women of the long house had gathered about her. The squaws of the village had come and gone. Nearly all the day her husband had been sitting near her by the fire, saying nothing, pulling meditatively at his pipe. He was a war chief; but no war paint slashed his face today. There was at least an interval of peace and the gentle Algonquin was glad.

Finally, without a word he slipped out of the cabin, and now for the first time Kahenta was alone. Timidly she glanced about the deserted long house. There was no sound but the hesitant crackling of the fire. She leaned over the child and it opened its eyes. She picked it up, wrapped the soft doeskin around it and rocked it in her arms, humming softly a poignant little tune to which gradually she found the words. It was Brébeuf’s lullaby for the Christ Child, written for his Indian children at Christmas time long ago, when he had just come to the land of the Hurons.

“Within a lodge of broken bark

The tender Babe was found;

A ragged robe of rabbit skin

Enwrapped His beauty round.

And as the hunter braves drew nigh

The Angels’ song rang loud and high:

‘Jesus, your King, is born; Jesus is born.

In excelsis gloria.’”

Kahenta clasped her papoose more closely. Then more words came:

“The earliest moon of winter time

Is not so round and fair

As was the ring of glory on

The helpless infant there.”

Kahenta’s voice softened to a whisper. The child’s eyes were closing.

“While chiefs from far before Him knelt,

With gifts of fox and beaver pelt”...

Kahenta’s head bent lower. Her words trailed slowly into silence. The child was asleep.

A French woman had taught her the words of this song when she was a child. How she longed for her now! In this cruel pagan land to which she was a stranger, would her little girl ever learn as she had learned, to know and love Rawenniio, the white man’s God? Would the Blackrobe ever come to the castle of the Turtles and baptize her? A look of terror crossed her face. If he did, the Mohawks would certainly kill him as they had killed Ondessonk, whom the French called Father Jogues. She remembered the morning well. It was when she was a little girl, only ten years ago, and the French woman’s face had turned white as she told the harrowing story. It happened in this very village of Ossernenon and she wondered which was the long house that he was entering when the tomahawk struck him. Well could she visualize the scene of torture; for her own long house faced the square where the scaffold stood, and often, too often, she heard the cries of the captives and could do nothing but hide her head in her hands and pray. Had Kenhoronkwa, her husband, been one of Ondessonk’s torturers? It was more than likely. She shuddered.

And yet she must not think unkindly of him. He had saved her from a captive’s fate by making her his wife. As though it were yesterday she recalled the agonizing journey of the defeated Algonquins through forests and over lakes, along the war trail from the St. Lawrence into the Valley of the Mohawks, to her a dark and desolate country until today. The infant lay quietly upon her heart. The fire was burning low and the place was full of shadows. What would its future be? The child was a Mohawk—that, she must concede—but she was Algonquin, too. Since the Mohawks were a conquering tribe she would never, perhaps, be torn from all that she loved, as her mother had been. Only a few weeks ago the tragic story had repeated itself. The Iroquois had swept over the Isle of Orleans, destroyed the nation of the Hurons, and once more crowded the Turtle village with captives. Rumors had spread that the neighboring Onondagas were willing to make peace with Onnontio the French governor. Not so the Mohawks. They were continuing their raids upon the French frontier, and Kenhoronkwa was a war chief. He would have nothing to do with the French or the Blackrobes.

Again she remembered Father Jogues and trembled. She had been told about his mutilated hands and about the severed head placed high upon the palisade ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- INTRODUCTION

- FOREWORD

- FOREWORD

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER