![]()

PART ONE

Background

![]()

Chapter One

WARFARE IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Causes of War

Countries in the ancient Near East went to war for a variety of reasons. As might be expected, self-defense or defending an ally who was attacked were common reasons for going to war. For example, Ramses III, the pharaoh of Egypt during the twelth century BCE, defeated the Sea People (who included the Philistines known from the Bible) when they attacked Egypt.1 The Amarna letters, which were written mostly by Canaanite kings to Pharaoh Akhenaten around 1350 BCE, often requested help for self-defense, such as in this letter: “Moreover, note that it is the ruler of Ḫaṣura who has taken 3 cities from me. From the time I heard and verified this, there has been waging of war against him. Truly, may the king, my lord, take cognizance, and may the king, my lord, give thought to his servant.”2

Another major reason for going to war sounds strange to modern ears: protection against chaos. Nations saw chaos as manifested in such things as broken treaties and evil deeds. Even chaos found outside their borders could be perceived as perilous because it might endanger order everywhere in the world. In modern terms, this might be compared to how we approach human rights: a country might go to war to protect a minority population being oppressed within another country in order to uphold ideals of universal human rights. In Egypt, the idea of order was expressed through the term maat, while isft was the chaos that always threatened to overwhelm the world. One of the primary duties of the pharaoh was to encourage maat in the world and defeat isft.3 Conquering a foreign country defeated the chaos there and brought order; for example, Ramses II (thirteenth century BCE) claimed that travelers were safe in the lands under Egyptian control: “Thereafter, if a man or woman went out on business to Syria, they could even reach the Hatti-land without fear haunting their minds, because of (the magnitude of) the victories of His Majesty.”4 Assyrians viewed the world in a similar way, as demonstrated by this quotation from Esarhaddon, king of the Neo-Assyrian empire in the seventh century BCE: “When the god Aššur, the great lord, (wanted) to reveal the glorious might of my deeds to the people, he … empowered me to loot (and) plunder (any) land (that) had committed sin, crime, (or) negligence against the god Aššur.”5

Like today, the ancients did not describe the cause of their wars as the desire to acquire plunder, but it clearly played an important role in their decisions. For example, one king wrote to his ally about why they should go to war together: “ ‘Fatten’ your troops with spoils (so that) they will bless you.”6 In some graffiti about a military campaign, an Egyptian soldier wrote: “There was no fighting; I shall not bring a Nubian back (as captive) from the land of the Nubians.”7

Preparation for War

While the battles themselves attract the most attention, wise generals know that preparation for war is just as important as actually fighting the battles. Even though they did not have the sophisticated technology available to modern armies, leaders were still able to gather significant amounts of information about their enemies. In some cases foreign nationals themselves provided information to kings; indeed, an important part of being a good vassal king was keeping one’s suzerain—the conquering king—informed. One Assyrian treaty with a vassal includes this clause: “[Nor] will you conceal from me anything that you hear, be it from the mouth of a king, or on account of a country, (anything) that bears upon or is harmful to us or Assyria, but you will write to me and bring it to my attention.”8 Scouting while on campaign was also important as a way to learn about local terrain, specifics about the composition of the enemy army, and the location of the enemy. Ramses II recounts a significant scouting failure when captured Hittite scouts convinced the Egyptians that the Hittite king was still at home, when in reality he was already marching to battle.9

Leaders also had to muster troops for the battles. Nations usually employed their own people to serve in their armies and created various means of ordering that process. However, many nations also used foreign troops in their armies. For example, after the defeat of Samaria at the hands of the Assyrians in 722 BCE, a group of Israelite charioteers served in the Assyrian army under Sargon II: “I conscripted two hundred chariots from among them into [my] royal (military) contingent.”10 In addition, an Egyptian scribal satire about the soldier’s life refers to prisoners being branded when they became attendants of the army.11

Other major preparations for war involved either marching to the battlefield or strengthening fortifications. For long-distance marches, kings usually began their campaigns in the spring (2 Sam. 11:1). For example, Pharaoh Thutmose III began his march against Megiddo in early April, when the wheat harvest was finishing.12 The average speed of ancient armies seems to have been around 10–13 miles per day, as they traveled on foot.13 Nature frequently posed a danger as great as enemy soldiers. Kings often boasted of conquering mountains, deserts, or rivers in terms similar to defeating the enemy, as in this quotation from the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser I: “In Mount Aruma, a difficult area which was impassible for my chariots, I abandoned my chariotry. Taking the lead of my warriors I slithered victoriously with the viciousness of a viper over the perilous mountain ledges.”14 Supplying water and food for these long marches was often complicated as well, since armies could only carry a limited supply with them. Armies established supply depots along campaign routes, enlisted allies to provide supplies, or forced local residents to give them provisions. While the attacking army was marching, the defenders strengthened fortifications, generally focusing on fortifying their major cities but often including outlying fortresses as well. Second Chronicles 32:1–5 provides the account of Hezekiah’s fortification of Jerusalem in preparation for the arrival of the marching Assyrian army.

Battles and Weapons of War

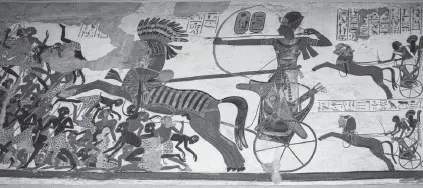

Armies in the ancient Near East fought two main kinds of battles. First, some battles were fought in the open field, though unfortunately specific tactics for these battles are unknown. Chariots were developed in the mid-second millennium and played an important role as mobile missile platforms, allowing archers on the chariots to draw near to the enemy, fire at them, and then retreat without easily being attacked.

Figure 1. Cast of Ramses II relief from Beit el-Wali. British Museum, London.

Figure 2. Cavalry of Ashurnasirpal II. British Museum, London.

Figure 3. Spearmen from the tomb of Mesehti. Cairo Museum, Egypt. Photo by Udimu / CC-BY-SA-3.0.

The supremacy of the chariot continued until cavalry took over their role around 800 BCE. The bow was the most important distance weapon in the ancient Near East: the presence of a bowman on a chariot or the back of a horse would have terrified the enemy. The most common hand-to-hand offensive weapon was the spear. Although in earlier times maces and axes were used, they were displaced by the sword. However, none of these weapons were as widespread as the spear. Defensive items such as leather or linen scale armor became more common throughout the time period, and helmets and shields were frequently used. Metal armor remained rare.

The second common kind of battle was a siege, which would have been the default choice for defenders since the large walls of major cities would have prevented a quick victory for attacking armies. During times of siege, surrounding villages were often emptied as the rural population fled to the cities. Since keeping an army in the field for a long period of time was difficult, defenders could effectively be victorious if they caused the attacker to return home. Attackers could win by remaining until the city’s food supplies dwindled, causing horrific starvation conditions inside the city (2 Kings 6:25–29). Direct assaults on the city could involve the use of battering rams, tunneling, sapping, ladders, and siege towers. Defenders developed a variety of strategies against these direct assaults, such as setting siege towers on fire and building a counter ramp inside the city. One of the most famous sieges is that of the Judean city of Lachish in 701 BCE by the Assyrians.

Other kinds of battle were less common. Since the armies of the ancient Near East were largely land based, naval battles were infrequent. Also, in spite of the story of David and Goliath, single combat—in which two representatives fought each other—was very rare in the ancient Near East. Finally, deception in battle (such as the use of surprise or night attacks) was practiced at times, especially during sieges or by smaller kingdoms that had fewer choices.

Figure 4. Assyrian soldiers. Museum of the Ancient Near East, Berlin. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber / CC-BY-SA-3.0.

Figure 5. Egyptian siege by Ramses II. Ramesseum, Theban necropolis, near Luxor, Egypt.

Figure 6. Assyrian siege by Sennacherib at Lachish. British Museum, London.

Results of War

One obvious result of battle for the defeated was flight, which the victors loved to describe with vivid metaphors. For example, Sennacherib, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the seventh century BCE, said, “They abandoned their tents and, in order to save their lives, they trampled the corpses of their troops as they pushed on. Their hearts throbbed like the pursued young of pigeons, they passed their urine hotly, (and) released their excrement inside their chariots.”15 The immediate action of the victors was often to take plunder: Thutmose III rebuked his troops for plundering the enemy before the battle was even over.16 Plunder and prisoners were primari...