![]()

CHAPTER 1

MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICY CONTRIBUTION TO THE POST-COVID-19 PANDEMIC ECONOMIC RECOVERY

Victoria Cociug and Larisa Mistrean

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The COVID-19 crisis is a major shock to the global economy, with serious repercussions on financial markets. Most economies, especially high-income ones, have made considerable efforts, including financial ones, to stimulate aggregate demand in the face of a loss of income on the one hand and to maintain the production potential of companies on the other. This fact required the intervention through various instruments on the money market, but also the mention of the money creation capacity of the banks through the lending mechanism. Apparently, this should have affected the stability of banking systems by increasing the credit risk assumed, but this was avoided because banks are better capitalised and the regulatory framework, including the macroprudential one, was strengthened after the financial crisis of 2007–2009. Therefore, the national authorities had sufficient leeway to respond to the recession and market instability caused by the pandemic by relaxing prudential requirements.

Aim: A theoretical review of literature and good practice of developed banking systems on how macroprudential policy can supplement expansionary monetary policy in overcoming the pandemic crisis. Identifying the risks for the excessive use of relaxed macroprudentialism and formalising recommendations to combine it with monetary policy instruments to overcome stressful situations for banking systems.

Method: In order to study the subject approached in this chapter, there were applied the following research methods, such as analysis and synthesis of conceptual approaches of macroprudentiality and the tools they use, deduction and induction, in order to elucidate the influencing factors using the relaxation of macroprudentiality in the context of pandemic crisis and research on the high-income states experience in order to formulate conclusions and opinions.

Findings: The authors find that countries have responded quickly to the outbreak of the crisis by easing capital and liquidity requirements, or at least refraining from the previously planned tightening. At the same time, the authors noticed that loan-based measures and minimum reserve requirements were rarely relaxed and risk weights were not changed at all.

Originality of the Study: The correlation of different monetary and macroprudential policy instruments in the need to relax them, the analysis of possible risks and the formulation of conclusions on the usefulness of applying these methods to solve the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications: Our results suggest that the macroprudential instruments can only be applied if banking systems have previously succeeded in consolidating the capitalisation of banks. A restrictive macroprudential policy can create premises for the use of excess capital in situations such as that generated by the pandemic, but it is recommended only to economies where overregulation does not affect development in periods of normal evolution.

Keywords: Macroprudential policy; Basel; capital buffer; risk indicators; risk-weighted assets; Tier 1 capital; capital adequacy requirements

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of 2020, an entire world has been struggling with an unexpected major shock: the COVID-19 pandemic. The crisis has affected all segments of the economy, triggered by non-economic factors. Most states have accessed financial support instruments, such as financial incentives and aid to support the real economy, but the biggest pressure has been on monetary policy, as this aid has been financed from non-monetary issues. Among these instruments can be mentioned the fiscal holidays for the companies affected by COVID-19, fiscal incentives, meant to maintain the vitality of the business, but also some special programmes to support the SME. Thus, in the first months of the lockdown alone, about 700 small and medium business support programmes were announced (Nygaard & Dreyer, 2020). However, most countries have used the injection of money into the economy to stimulate aggregate demand, acting in the direction of maintaining the purchasing power of the population.

Under these conditions, in order to reduce the use of traditional monetary policy instruments, some states have used discretionary instruments, those of macroprudential policy, which by applying the correct correlation can influence the money supply through the channels of interest rate and credit much more cost-effectively. Thus, the issue of the interaction of monetary policy with the macroprudential one, established by the IBRN (IMF), is a primary one for research.

Surprisingly, however, this economic crisis, which has had and continues to have a severe impact on all sectors of the economy, has not affected the banking sector, even though the solvency of bank borrowers has fallen sharply and the credit risk has risen as a result. In this context, the relaxation of some macroprudential restrictions had the opposite effect – the banks remained sufficiently capitalised and instead of being part of the problem, they were part of the solution. The banking sector has managed to support the economy through continuous lending, including the sectors most affected by the lock-in measures. Compared to past episodes of crisis, there are two main reasons why banks have played a different role in this crisis (Bezzina, Grima, & Mamo, 2014).

Firstly, in terms of capital and liquidity, the banking sector, due to the restrictions gradually imposed by the introduction of Basel III, was much better prepared than it was before the great financial crisis of 2007–2009. Finally, yet importantly, this was due to the progress of strengthening macroprudential regulatory standards that formed a sufficient buffer to pass over the period of declining credit portfolio quality.

Second, lending during the pandemic was aided by decisive government support measures, such as public loan guarantees and direct and indirect support for firms, and aid measures taken by micro- and macroprudential authorities. Specifically, banking supervision in most countries allowed banks to operate temporarily below the capital level defined by the Pillar II guideline and the combined amortisation requirement and advised banks to refrain from paying dividends and share repurchases. On the macroprudential side, several national authorities have either announced a complete cancellation of capital countercyclical buffers or revoked previously announced increases in these and other buffers. Together, micro- and macroprudential measures have been a strong signal to banks that they should use existing capital buffers to continue to provide key financial services and absorb losses, while avoiding sudden and excessive indebtedness that would be detrimental to the economy. However, let us look in more detail at how each of these tools works separately.

Thus, this chapter proposes to discuss the mechanism of involvement of macroprudential policy instruments in helping to overcome the liquidity shortage faced by the economies affected by the need to stop the activity of the real sector during the pandemic crisis. The aim of this research is to demonstrate that macroprudential instruments can be taken towards relaxation, in order to increase access to credit for companies affected by the pandemic without causing major problems to the stability of the banking sector. At the same time, it is desired to identify the limits of application of macroprudential deregulation and how to combine its instruments with those of monetary policy in order to maintain acceptable financial conditions for a relaunch of economic activity in the post-pandemic period.

THE GENESIS OF MACROPRUDENTIALITY

The banking system is the basic element of the functioning of any country due to the fact that banks, in the process of financial intermediation, ensure the channelling of temporarily available resources collected from the market to households and/or businesses that need them, but also organise and perform settlements and payments related to both internal and external economic activity, in order to obtain profits from the activity carried out. Therefore, banks, representing the central element of the financial system of any country, are characterised by:

a high level of financial interdependence (both with their customers and with other correspondent banks);

operation with liquid means that can be easily alienated or demanded for reimbursement by depositors, with a high leverage effect; and

operates under conditions of increased information asymmetry in relation to its customers (on the one hand the value of financial assets and the ability to pay the bank’s debtors are uncertain and dependent on unpredictable external factors, and on the other hand the confidence in the bank’s ability to meet its commitments is vital for its operation), all taken together as elements of uncertainty, which determines both the individual fragility of banks and the banking system as a whole, following the possibility of domino effects (chain bankruptcy of several banks).

Those mentioned, but also the fact that the costs of bank failures are consistent, and those of bank crises are simply huge, as can be seen from several specialised works, such as estimates made by Barth, Caprio and Levine: “Fiscal costs of banking crises, which occurred in developing countries in 1980–1990, calculated separately, exceed the amount of 1 trillion US dollars, which, calculated at present value, is approximately equal to the total amount of which benefitted developing countries between 1950 and 2001” (Barth, Caprio, & Levine, 2006), determines the need for strict regulation of banking, which historically proved to be the strictest of the regulations applied to any economic activity.

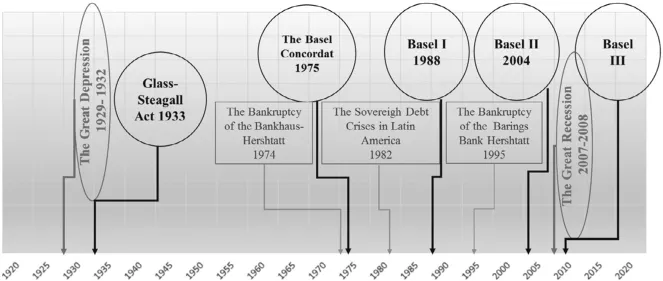

The process of drafting and institutionalising banking regulations, especially prudential ones, has been a long one. This, in essence, represented reactions of the authorities and the private sector to resonant bank failures and/or, in particular, large-scale financial (banking) crises, reflecting the vision at that time on their causes and possible solutions. It can therefore be considered that banking regulation has naturally developed as sets of reactions set out in the form of institutional rules or arrangements designed to prevent similar situations from occurring in the future (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The Evolution of Prudential Regulations Depending on Financial Crises. Source: Author’s compilation.

In times of financial crisis, each state tried to limit the excess risks that its banking sector could assume through various prudential instruments, establishing certain activity restrictions. However, with the trans-nationalisation of banking, the limits valid for one market proved ineffective for another, so the need to move from individual percentage to common restrictions for several banking systems was configured (Grima, Hamarat, Özen, Girlando, & Dalli-Gonzi, 2021; Pavia, Grima, Romanova, & Spiteri, ...