Soil Organic Matter and Feeding the Future

Environmental and Agronomic Impacts

- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Soil organic matter (SOM) is the primary determinant of soil functionality. Soil organic carbon (SOC) accounts for 50% of the SOM content, accompanied by nitrogen, phosphorus, and a range of macro and micro elements. As a dynamic component, SOM is a source of numerous ecosystem services critical to human well-being and nature conservancy. Important among these goods and services generated by SOM include moderation of climate as a source or sink of atmospheric CO2 and other greenhouse gases, storage and purification of water, a source of energy and habitat for biota (macro, meso, and micro-organisms), a medium for plant growth, cycling of elements (N, P, S, etc.), and generation of net primary productivity (NPP). The quality and quantity of NPP has direct impacts on the food and nutritional security of the growing and increasingly affluent human population.

Soils of agroecosystems are depleted of their SOC reserves in comparison with those of natural ecosystems. The magnitude of depletion depends on land use and the type and severity of degradation. Soils prone to accelerated erosion can be strongly depleted of their SOC reserves, especially those in the surface layer. Therefore, conservation through restorative land use and adoption of recommended management practices to create a positive soil-ecosystem carbon budget can increase carbon stock and soil health.

This volume of Advances in Soil Sciences aims to accomplish the following:

- Present impacts of land use and soil management on SOC dynamics

- Discuss effects of SOC levels on agronomic productivity and use efficiency of inputs

- Detail potential of soil management on the rate and cumulative amount of carbon sequestration in relation to land use and soil/crop management

- Deliberate the cause-effect relationship between SOC content and provisioning of some ecosystem services

- Relate soil organic carbon stock to soil properties and processes

- Establish the relationship between soil organic carbon stock with land and climate

- Identify controls of making soil organic carbon stock as a source or sink of CO2

- Connect soil organic carbon and carbon sequestration for climate mitigation and adaptation

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Enhancing Fertilizer Use Efficiency by Managing Soil HealthEmerging Trends

List of Abbreviations

B: | Boron |

CA: | Conservation agriculture |

Cl: | Chlorine |

Cu: | Copper |

DAP: | Diammonium phosphate |

FAO: | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

Fe: | Iron |

FUE: | Fertilizer use efficiency |

GHG: | Greenhouse gases |

IFA: | International Fertilizer Association |

IFAD: | International Funds for Agricultural Development |

IFDC: | International Fertilizer Development Center |

IPNI: | International Plant Nutrition Institute |

ISFM: | Integrated soil fertility management |

K: | Potassium |

MAP: | Monoammonium phosphate |

Mn: | Manganese |

Mo: | Molybdenum |

N: | Nitrogen |

NPK: | Nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium |

NUE: | Nitrogen use efficiency |

P: | Phosphorus |

PFP: | Partial factor productivity |

SOM: | Soil organic matter |

SSP: | Single super phosphate |

SSNM: | Site-specific nutrient management |

TSP: | Triple super phosphate |

UNIDO: | United Nations Industrial Development Organization |

USDA: | US Department of Agriculture |

WFP: | World Food Programme |

WHO: | World Health Organization |

Zn: | Zinc |

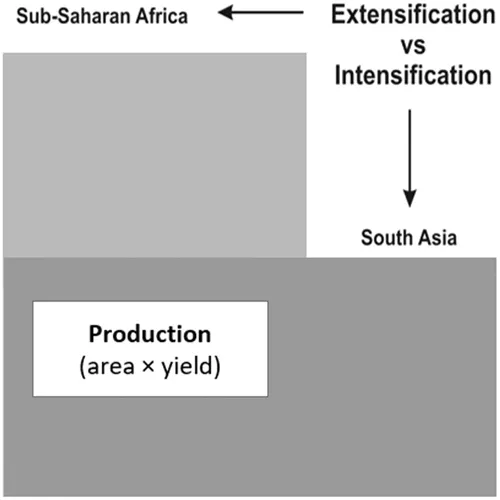

1.1 Introduction

| Number of Malnourished People (Millions) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

2005 | 2016 | 2019 | 2030* | |

WORLD | 825.6 | 657.6 | 687.8 | 841.4 |

AFRICA | 192.6 | 224.9 | 250.3 | 433.2 |

Northern Africa | 18.3 | 14.4 | 15.6 | 21.4 |

Sub-Saharan Africa | 174.3 | 210.5 | 234.7 | 411.8 |

ASIA | 574.7 | 381.7 | 381.1 | 329.2 |

Central Asia | 6.5 | 2.1 | 2 | N.R. |

Eastern Asia | 118.6 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

Southeast Asia | 97.4 | 63.9 | 64.7 | 63 |

Southern Asia | 328 | 256.2 | 257.3 | 203.6 |

Western Asia | 24.3 | 29.2 | 30.8 | 42.1 |

| N.R., Not Reported. | ||||

| Do Not Reflect the Potential Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina 2013). | ||||

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Editor

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Enhancing Fertilizer Use Efficiency by Managing Soil Health: Emerging Trends

- Chapter 2 Conservation Agriculture: Carbon and Conservation Centered Foundation for Sustainable Production

- Chapter 3 Relating Soil Organic Carbon Fractions to Crop Yield and Quality with Cover Crops

- Chapter 4 Global Spread of Conservation Agriculture for Enhancing Soil Organic Matter, Soil Health, Productivity, and Ecosystem Services

- Chapter 5 The Effects of Soil Organic Matter and Organic Resource Management on Maize Productivity and Fertilizer Use Efficiencies in Africa

- Chapter 6 Cover Cropping for Managing Soil Organic Carbon Content

- Chapter 7 Fertilizer Use in the North China Plains for Improving Soil Organic Matter Content and Crop Yield

- Chapter 8 Managing Rain-fed Rice Farms for Improving Soil Health and Advancing Food Security: A Meta-Analysis

- Chapter 9 Soil Organic Matter: Bioavailability and Biofortification of Essential Micronutrients

- Chapter 10 Raising Soil Organic Matter to Improve Productivity and Nutritional Quality of Food Crops in India

- Chapter 11 Role of Legumes in Managing Soil Organic Matter and Improving Crop Yield

- Chapter 12 Managing Soil Organic Carbon in Croplands of the Eastern Himalayas, India

- Chapter 13 Soil Organic Carbon Restoration in India: Programs, Policies, and Thrust Areas

- Chapter 14 No-Till Farming in the Maghreb Region: Enhancing Agricultural Productivity and Sequestrating Carbon in Soils

- Chapter 15 No-Till Farming for Managing Soil Organic Matter in Semiarid, Temperate Regions: Synergies, Tradeoffs, and Knowledge Gaps

- Index