![]()

Chapter 1

ALLOSAURUS AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY

INTRODUCTION TO EVOLUTION

“I don’t see how we’re ever going to agree if you suggest that natural laws have changed. It’s magical [thinking].”

— Bill Nye (2014), the science guy, in a debate about evolution vs. creation

About 66 million years ago I’m pretty sure it was on a Tuesday, something truly terrible happened in modern-day Mexico. An extremely large meteorite (10 km wide) obligingly obeyed the laws of physics and smashed into the planet we have since come to adore and abuse. Striking in the Yucatan Peninsula, the massive meteorite created a blast some 30 billion times more powerful than the sum of the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. In an instant, a tropical paradise became a smoldering crater 20 km deep and 160 km wide. Massive tsunamis, earthquakes, and volcanoes were triggered worldwide. Climate change, forest fires, and acid rain must have occurred on an unimaginable scale. Some scientists think it may have taken a decade just for the thick clouds of ash and dust to settle. For the first time in millions of years, it became a terrible time to be a dinosaur. As thick clouds of dust choked the planet, even the cleverest and most resourceful dinosaurs proved to be unprepared to survive on a burning-then-freezing planet practically devoid of plant life (Brusatte et al., 2014). Lloyds of London was not answering any phone calls.

Virtually all evolutionary biologists believe this epic tragedy for dinosaurs became a wonderful opportunity for mammals like me and you. Actually, the typical mammals who were lucky enough to survive in the wake of this planetary disaster resembled a chipmunk a lot more than they resembled me and you. Beginning with descendants of the chipmunkish Morganucodon (aka Morgie), many ancient mammals survived the cosmic disaster and then evolved to become the incredibly diverse family of always warm and usually fuzzy creatures that zookeepers and preschoolers know and love. Post-asteroid, most of Morgie’s mammalian descendants had some huge advantages over most dinosaurs. For starters, having fur and being good at staying warm probably helped small mammals survive the harsh nuclear winter that helped extinguish all the big dinosaurs. It was probably an even bigger advantage for small mammals that they could live in small places, away from the fire, snow, and acid rain. Morgie, for example, was only about 10 cm long, roughly as big as you see her in Figure 1.1. If you’re paleontologically sophisticated enough to know that many birdlike dinosaurs also survived this mass extinction, you probably know one likely reason why many of them were able to do so. It’s a lot easier to survive a lengthy global famine when you eat like a bird than when your idea of dinner is half a ton of fresh grass, or filet of Triceratops.

Figure 1.1 Artist Michael H.W.’s impression of Morgie, one of the first known proto-mammals. Morgie’s fur, special jaws, and mammalian inner ear bones set her apart from dinosaurs or reptiles. You share quite a bit of her DNA (her genome).

HOMOLOGY, PALEONTOLOGY, AND PSYCHOLOGY

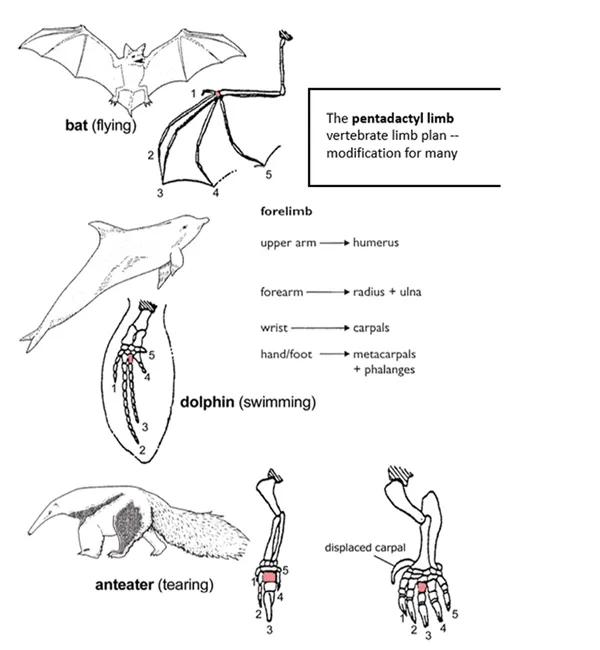

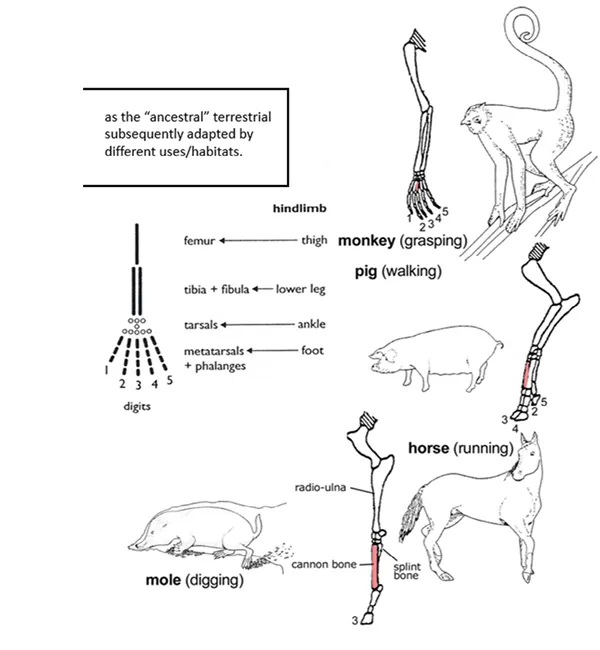

In the millions of years since the massive asteroid strike, the earth’s inhabitants have slowly but dramatically diversified. About 15–20 million years after the strike, some of Morgie’s mammalian descendants gradually returned to the oceans that spawned all life on earth, eventually evolving into modern whales and dolphins. Incidentally, one of the many reasons we know that whales and dolphins evolved from land mammals is that their skeletons strongly resemble those of other mammals. For example, as you can see in Figure 1.2, dolphins have forelimb (“flipper”) bones that strongly resemble the front limb bones of virtually all mammals. Dolphins even have five “finger” bones just like we do, despite the fact that dolphins look totally ridiculous in gloves. The tendency for animals that share a common ancestor to share traits with one another is known as homology, and it occurs because animals that have an ancestor in common have genes in common. Some whales and dolphins have vestigial (tiny, left over) rear leg bones that never emerge from their bodies. In addition to breathing air, nursing their young, and having special mammalian ear bones, dolphins and whales also share a much greater percentage of their genome with you than they do with the sharks or other large fish that they more closely resemble on the outside. Finally, another piece of evidence strongly suggesting that dolphins and whales evolved from land mammals has to do with the way they swim. Unlike fish, which propel themselves by moving their tails side to side, whales and dolphins move their spines up and down to swim. As a wolf or lion runs, the same thing happens to its spine. Notice that mode of swimming is a behavioral trait grounded in a whale’s skeletal structure. It’s important to note that homology applies to behavioral as well as physical traits, and many of these behavioral traits are grounded in the brain as well as the body. Numerous arguments in this book involve ways in which human beings behave like other mammals, because of their mammalian bodies and/or brains.

It would be another 20 million years after some mammals returned to the oceans (about 25–30 million years ago) before the common ancestors of monkeys and apes split into these two different groups. The apes, by the way, are the ones without tails, and one particular species of great ape, the hominid Homo sapiens (you and me), emerged only about 200,000 years ago (Ermini et al., 2015). So our species has only been around for about a fifth of a million years. In fact, it was only 11,000 years ago that we made the agricultural – and then cultural – leaps that have made us the most successful and destructive animals on the planet (Diamond, 1997). I’ll say more about that later. For now, it seems safe to say that no human leaps of any kind would have ever happened if the dinosaurs still ruled.

If you’re wondering what this paleontology lesson has to do with psychology, the beginning of the answer is that you and I are mammals. Mammals and proto-mammals lived alongside dinosaurs for more than 100 million years without becoming a very diverse family. Seventy million years ago there were no bats, whales, giraffes, or gorillas. They did not exist because tens of millions of years before mammals hit the scene (or exploded in the Pliocene), dinosaurs had cornered the market on the ecological niches needed to support such highly unusual modern-day mammals. Morgie and most of her ancient mammalian cousins filled a unique environmental niche by eating bugs and being agile enough to stay out of the way of T. rex (or T. rex’s tinier cousins). Although there were some notable exceptions to this rule of tiny rat-likeness among ancient proto-mammals, mammals never became diverse and populous until the dinosaurs became extinct (Meng et al., 2011; O’Leary et al., 2013).

Figure 1.2 Jerry Crimson Mann’s illustration of homology, which is the idea that related species often share common traits, because they share genes derived from a common ancestor. Despite their extreme diversity, mammals all have amazingly similar forelimb and hind limb bones.

Thus, in the absence of that deadly meteorite strike, the chances are virtually zero that any species of dinosaur would have ever evolved into a quirky, brainy, highly social creature that cares for its young for a couple of decades, sings Ave Maria, conducts psychology experiments, and is susceptible to both yellow fever and Bieber fever.

Consider a whole class of animals that are even more ancient than the family loosely known as dinosaurs. Insects were around well before the dinosaurs, and they will probably be here long after human beings are extinct. But it’s exceedingly unlikely they will ever create art or write poetry. In contrast, you and I can do these uniquely human things, as well as a long list of simpler things done only by mammals. There is also a list of things done almost exclusively by vertebrates, by the way, but this discussion would take us back at least 500 million years rather than 66 million years (Kolbert, 2014; Shubin, 2008). Suffice it to say that because we are mammals, we have a lot more in common with our mammalian relatives than most people appreciate (de Waal, 1996; Diamond, 1992).

We’re not that special

You may have heard that we share more than 98% of our genes with chimpanzees. Perhaps that’s not so shocking. Consider the following thought experiment, adapted from Jared Diamond (1992). Take a male chimpanzee, and sedate him (so he doesn’t rip anyone’s arms off – chimps are incredibly strong). Now shave his entire body, put a Boston Red Sox cap on him, and drop him onto a New York City subway seat – making sure the train is headed to the Bronx. On second thoughts, replace the Red Sox cap with a Yankees cap – so no one rips the poor chimp’s arms off. More than 98% of subway passengers will see an ugly old man who should be arrested for indecent exposure. Chimps are a lot like human beings. This is why zookeepers who want to control their chimpanzee birth rates can simply give their female chimps human birth control pills. And it’s presumably why chimpanzees make tools, deceive each other, organize themselves into social groups, go to war, inspect the genitals of newborns to assess their sex, have sex face to face, and sometimes shake hands to greet one another – all very much like we do. According to experts such as Frans de Waal and Jared Diamond, we have way more in common with chimps than most people could imagine.

Speaking of chimps, both people and chimps also have a little something in common with bananas. What ...