![]()

1

A HEROIC LAUGHTER

Behold, I bring you the Superman!

—Friedrich Nietzsche

IT was an evening in May 1966. Satyajit Ray, world-feted director of the Apu Trilogy and Charulata among others, dialled up a number from his four-room, open-terraced 3, Lake Temple Road residence that swiftly passed Sarat Chatterjee Avenue, kissed the leafy Southern Avenue, ran headlong along Lansdowne Road, jumped A.J.C. Bose Road, snaked past Hungerford Street and on hitting Moira Street turned right, entering the second floor of a sprawling apartment, also on plot no. 3, a little more than five kilometres away. Uttam Kumar, Bengal’s legendary matinee idol, took the call. “Uttam”, Ray’s baritone boomed from across the speaker of the rotary dial phone, “Nayak premieres tomorrow at Indira Cinema. I hope you will be there.” “But Manikda, the press and public will be in attendance. Do you think I should go? There might be pandemonium”, the star reasoned. “Uttam, don’t forget it’s a Satyajit Ray film. Please be there”, Ray commanded. For a moment the lines fell silent, then they sprang to life again. “Sure, Manikda”, came the reply.

Next day, the news was out quickly. By late afternoon, crowds thronged every bit of road leading to Bhawanipur, south Calcutta’s movie haven. Parts of the city’s southern neighbourhoods had to be barricaded. Accosted by the volatile crowd, Uttam Kumar’s car, a Chevrolet Impala, had to abandon the usual route of three kilometres and was piloted through the by-lanes of Chakraberia and Beltala. As expected, the venue too was chock-a-block, with hundreds guarding the gates for one glimpse of the star. Uttam was cagey, though this kind of raucous fandom had greeted him on every such occasion for over a decade by then.

On reaching the gleaming, newly whitewashed Indira Cinema, Uttam Kumar disembarked sprightly, managing to escape the waiting hundreds and swiftly moved into the confines of the building. He was escorted to his seat inside the hall cloaked in complete darkness. But it was too late to conceal his presence. The cushy theatre was shaking under the weight of uproarious greeting, ‘Guru’, ‘Guru’, with demands to see the star in person. Alarmed, the theatre manager rushed to Ray, already seated. “Sir, if we don’t bring him up on stage there will be a serious law-and-order issue. Can I?” he asked. Ray nodded quietly. Minutes later, the lights came on and Uttam Kumar was seen standing on the raised platform in front of the screen. He raised his hand. The crowd fell silent, as if at the wave of a magic wand. Uttam looked straight ahead into the expectant eyes of a hundred restless heads seated in front. “I request you to please be silent and watch the film. Don’t forget it is a Satyajit Ray film. Please.”

This story, a piquant testimonial to two of Bengal’s foremost immortals is partly apocryphal. But that takes nothing away from what this tale testifies to—Ray’s sway over his cast, the plaint theatre manager; the affianced, vociferous crowd; and the phenomenal stardom of Uttam Kumar. In some ways, this tale, like the film that was premiering that day, encapsulates the fantasy that was Bengali cinema. And it is not Ray who colonised that cinema, either as fantasy or as commerce. It was Uttam Kumar. And only Uttam Kumar.

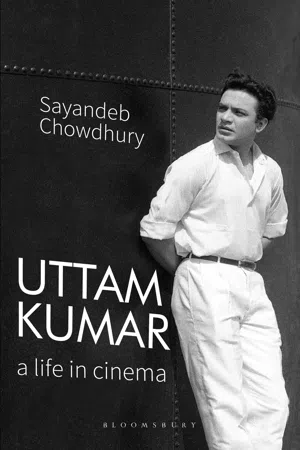

Image 1.1: Uttam near the Colosseum in Rome, 1966

(Photograph by Satyajit Ray)

Source: Ray archives.

There have been splendid actors such as Soumitra Chatterjee who have been feted internationally; there have been leading men such as Pramathesh Barua, who have defined a generation; there have been the ablest of performers such as Chhabi Biswas, whose screen presence can hardly be bettered. But there was (rather is) one who is all of the above: a leading actor, an extraordinary performer, a commercial magnet, a star-persona, an industry behemoth and a Bengali cultural talisman. There is only one icon of Bengali cinema—with all its highs and lows, its reach and range, its potential and its waste included—and that is Uttam Kumar.

INTIMATIONS OF IMMORTALITY

One of the most recognisable verities of Bengali cinema is that Uttam’s three-decade career lorded way above others, whether as actor or as star. What is less understood is how we infused his star-making charisma with the ebullient charm of a Cary Grant romance; the keen intelligence of a Humphrey Bogart whodunnit; or the lyrical vulnerability of a Marcello Mastroianni masterwork. And somewhere in between crept in the debonair infallibility of a Gregory Peck; or the alluring magnetism of a Gary Cooper. And every bit of this Hollywood transfusion was layered with affable, dependable, recognisable screen etiquette and a dulcet bhadralok distinctiveness. This was an irresistible combination and irreproducible with anyone else. Moreover, Atlas-like Uttam carried the industry on his shoulders and like Prometheus, gave it the fire of livelihood for three decades. In an industry famous for greasepaint plasticity, Uttam was a bloody original; in an art form full of conforming puppets, Uttam was an insurrectionist. He was no one’s marionette, except that of cinema itself. If all this sounds a bit outlandish, then so be it, because the hero has no better bedfellow than the hyperbole.

And yet, in case of Uttam, none of this is hyperbole. Uttam was indeed a star in the textbook sense, commanding and steering an entire popular industry and dominating its commercial and cultural assets between the early 1950s and late 1970s. Uttam was an informal and personal idol and at the same time a distant and collective cultural icon, soliciting fandom, affection, admiration and undying loyalty to his person and persona. He was not a product of the studio era and embodied the star era all by himself, over 200 films, about half of which remain re-collectible in Bengali cultural memory.

Let me illustrate this further. It has been almost seven decades since Uttam was first hailed as a figure of public adulation and four decades since Uttam Kumar passed away. Four long decades! We are in a world radically different from the one in which Uttam was born, attained his stardom and died. Over these seven decades, the life of a citizen of Bengal (or those with broader links with it) have passed through an alarming parade of changes. Technologies of belonging, climates and culture, objects and trinkets, manners and morals, moments and minutia—every other thing that constitutes the theatre of life—have passed into the graveyard of history. As it should be.

Among the handful who have managed to parry the bulldozing effects of time is Uttam. He seems undying, un-ageing, untouched by history, uncorrupted by the clock. His cult is of a rare variety, which not only shows no sign of abatement but has, in fact, increased incrementally since his death in 1980. To that end, Uttam’s star persona has managed to attain a distinguished afterlife; having included, over the years of television, a new generation of viewers with all their baggage of new cultural tastes. His cinema continues to draw weight, the umpteen re-runs of his films find a regular audience, his life and work is a perennial topic in addas, his departure publicly and secretly mourned. Moreover, Uttam’s birth and death anniversaries are still a Bengali annual cultural event—coercing supplements from broadsheets and periodicals; a retrospective or two; television broadcasts of key films; vague seminars and talks; and mostly other sundry acts of remembrance. His name is still a magnet for mass mobilisation used at will for unctuous political ends, as any observer of Bengal would know.

This is the labourious part of it. Uttam Kumar, every now and then, also emerges in spontaneous outbursts of memorialisation, continuing to live outside the bombast of official commemoration. His posthumous home is in fact in the archetypal reminiscence of the quintessential Bengali subject—his effortless omnipresence finding its way into personal memoirs, nostalgic ruminations and casual revisits. In quickly disappearing parlours of single-screen theatres across the city he seems to be ubiquitous. That’s expected. But Uttam’s smiling portrait also peeps out from sudden nooks and corners—neighbourly salons, dusty tailor-shops, bare-boned photo-studios, rusty sweetshops and grimy eateries—they either in thrall of his everlasting charm or inevitably peddling his visit in their midst many moons ago. The scale of Uttam’s easy visibility across Calcutta and towns of Bengal four decades after his death remains a startling case of fandom. The extent of appreciation of his cinema per se among those who deck up their surroundings with the likeness of him, however, remains a conjecture. Much more difficult is to gauge which Uttam this image refers to: the man, the actor, the star or the undying icon.

A finale of this fascination with the star is to be found in a series of portraits of Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray and Uttam Kumar lined one after the other in a meaningful sequence among poster shops and picture-framing vendors squatting across Calcutta’s embattled footpaths. This may be an inexplicable, even revolting, assortment for the bona fide Bengali intellectual but this coexistence carries within it a poignant metaphor of the city’s unforgettable relationship with the star.

That metaphor is about the inscrutable nature of stardom. In his memoirs, Uttam, then already a star, recalls being huddled into a train compartment from his car at the Howrah Station while on his way to an outdoor shoot. As usual, he waited anxiously, hoping for the train to depart as soon as possible, before there was inevitable chaos. While waiting, he saw a man peeking into his coupe inquiring if Uttam Kumar would be around. Before Uttam could say anything, the man restlessly passed on. He did not return and the train left the terminus. Minutes later another man, portly and affectionate, walked smilingly into Uttam’s cabin.

A young man was scouting for you. He came to our cabin and asked if Uttam Kumar was around. I stood up and said I was Uttam Kumar. He was very pleased and told me he was a big fan of Uttam Kumar but he did not know how he looked and when he heard that the star may be on this train, he was desperate to find him and seek his blessings. So this man took my blessing and walked out rather pleased, having finally met his idol whom he had never seen. He did not speak Bangla so he did not see your films but was yet a great fan.1

Uttam had only smiled in reply.

This ‘fan’, whose relationship to his idol is merely in the realm of imagination rather than visibility—something extraordinary for a film star—perhaps captures the apparently baffling assortment of Tagore, Ray and Uttam. It is not in the domain of comparative artistic greatness that one must measure this assortment, but in the individual cultural imagination—separately but powerfully embossed—that one must recall the unmistakable presence of Uttam Kumar in the cultural life of Bengal. In other words, if Tagore signifies a giant who roamed the world of letters and Ray a gifted life in world cinema, Uttam Kumar is the popular ‘hero’ for all time, the memorable, monumental, in fact, mythical matinee idol.

A STORIED LIFE

Uttam Kumar, born in his north Calcutta maternal home at Ahiritola on 3 September 1926 as Arunkumar Chattopadhyay, made a slippery acting debut in an unreleased Hindi film in 1947 and worked ceaselessly for over three decades till a July day in 1980 when he suffered another cardiac arrest on a movie set and passed away the day after.

A clerk at Calcutta Port Commissioners for several years, Uttam’s early days in his vocation were full of disappointment and dejection. As he found some work, he restlessly juggled his day job with his fervent moonlighting for studio assignments. His success came slow, often coercing out of him a petulant sigh, an all-too familiar outburst of a sophomore performing aspirant, who could not stake his job at the altar of his fledgling infatuation. He had stayed put, however, working the ledgers during the day and making rounds of the studios in his free hours.

The established templates of Bengali male stardom and screen masculinity were drawn from the high tables set up by Durgadas Banerji, Pramathesh Barua and Chhabi Biswas, all of who were, to quote Hamlet, ‘of the manner born’. They were rich, came from the local aristocracy, were professional by choice and romantic by disposition. Uttam was from a very modest, middle-class family, of ordinary schooling and a sketchy undergraduate education. Thinly built and emaciated, with a crop of oiled back-brushed hair, thick lips, a stout nose and small, curious eyes, the raw-boned Arun was lacking not just in degrees and rearing but also, in ‘heroic’ looks. So, when he at all got a chance to be in front of the camera, it was thanks mostly to the imploring of friends and relatives with connections in the industry. Otherwise, he had a hard time.

A year into the birth of the new Indian state, in 1948, Uttam did manage to make his first appearance on celluloid, but the film, Drishtidan, was forgotten. On the sets of films like Kamona, Morjada, Ore Jatri the nervous, emasculated, unobtrusive Uttam was an object of ridicule, taunted and teased by hangers-on in the studios. He soldiered on nervously, braving the roomful of cocky, loud naysayers. His first few films failed to draw any significant attention to his under-confident roles, whether as a side or lead actor, or to cause any box-office ripples. It was almost certain that Uttam was going to eke out a living out of the grinds of his lowly job or find inconsequential employment as a failed actor. Behind his back, they called him a ‘flopmaster general’; to his face they reminded him of the pedigree of his predecessors and the inadequacy of his aspiration. There was none to handhold him, none to supervise his talents or unleash his energies. A gawky Uttam continued to lap up the roles he got, improved upon his borderline stammering, read voraciously and trained himself in soccer, swimming, wrestling and music. And his films continued to come a cropper. Till the early 1950s, then, the dream of being a phenomenally popular matinee idol was not remotely in the reckoning, an unprecedented stardom not even a fanciful idea, nor did he imagine that one day he would be Ray’s protagonist and walk the red carpet at the Berlin Film Festival.

But the plot changed pattern since the time he found commercial success with Bosu Poribar (1952) and Sharey Chuattor (1953), the latter launching his fabled pairing with Suchitra Sen. Then, in 1954, a teary melodrama called Agniporikha gave him the stellar push. A precocious straggler of about twenty movies by then, Uttam, almost overnight, became a star. Between 1954 and 1957, a string of humongous box-office successes blurred the hardship and ignominy of his past and made him a cinematic attraction. His apparently average looks became a magnet of affection, his gait of imitation, his manners of romance, his smile of idolatry. Sometime in the winter of 1954, months before Ray’s Panther Panchali stormed the silos of the Western cinephile, a starry celluloid life premiered around the Tollygunge studios of Calcutta.

Uttam Kumar had a miraculous run at the box office for two full decades after he attained stardom. And the popularity he attained, both off and on the screen, is a stuff of lore. As he entered his mid-30s, he made efforts, not always with success, to be comparatively selective with his films, trying roles that suited his age and the temperament of the time. He also produced, directed, scored music and in one film, lent his mellifluous voice to his character. He found an actors’ union, endlessly petitioned for development of film infrastructure, funded both popular and crossover films, raised aid for the poor and the unsecured foot soldiers of his fraternity and was the loudest voice of concern in service of the industry that nurtured him.

Uttam’s acting fetched him laurels, awards (the first national award for acting to a male performer, six Bengal Film Journalists Association [BFJA] awards, commendations at Berlinale) and a huge and phenomenal fan following that pulverised both his privacy and person, put to interrogation his closely held middle-class upbringing and stalked his free movements till his last day. Given his sway, popularity and posthumous fame, it would be an act of underestimation to call Uttam just another star who reigned during his lifetime and continued to be an attraction after. Rather, for close to three decades, the cinematic materiality and imagination of Bengalis—culturally arrogant and historically zealous—were transported almost entirely upon the actor and his repertoire. Like the great acts that made him the iconic actor that he was, Uttam, at 5 feet and 11 inches, also stood much taller in death; whose purported shadow grew bigger and bigger with each passing day. Now, forty years into his afterlife, Uttam Kumar remains what he died as: the greatest icon ever to have graced Bengali cinema and also one among the principal cultural protagonists of the entire post-Tagorean Bengali public life.

Very few, one can argue, would have been able to fulfil this role of a cultural sovereign for so long; and that too with the limited armoury of popular cinema. How did Uttam manage to? One needs to map Uttam’s tremendous tenacity, diligence, charm and of course superlative talent; which were no doubt critical actors in making the star he was. One can also, no doubt, underline that Uttam’s stardom was at the cusp of collective aspiration, private fantasy and commercial custodianship. His is also a most curious case of an incremental felicity of posthumous value; a case that must be looked at with...