eBook - ePub

Master Spy

About this book

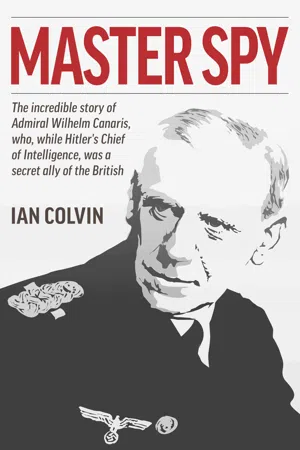

Master Spy, first published in 1951, recounts the career of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, who served as Hitler's Chief of Intelligence for nine years, but who was a quiet supporter of the German resistance to Hitler. Charming, exacting, mistrustful, and soft-spoken, Canaris became an Admiral during the WWI, but officially entered the Abwehr (Security Service) in 1935 of which he was later to become head. The book details the military and diplomatic interchanges in which he took part, including the incidents in which Canaris sabotaged and betrayed German plans, from the Munich pact to the proposed invasion of England and throughout the war, until his deposition by Hitler in 1944, and his execution in 1945. Perhaps most importantly, Canaris personally talked General Franco out of entering the war on Germany's side, arguing that he would be aligning himself with the wrong side. This prevented any assault on Gibraltar and kept the Mediterranean open for allied shipping. Without Canaris, the allies would have had significant difficulty in launching their North African, Sicilian or Italian campaigns.

After Stauffenberg's July 20, 1944 bomb plot against Hitler, the Canaris group was implicated, arrested and transferred to various concentration camps. In September 1944, incriminating documents were found in the safe of Abwehr officer Werner Schrader following that officer's July 28, 1944 suicide. Later, Canaris' complete personal diary was found in another safe at Zossen. The diaries made clear that Canaris had been playing a double game against the Nazis since before the war, enraging Hitler. On April 9, 1945, Canaris and several other members of the Abwehr resistance circle were put on trial in an SS kangaroo court and were hung at KZ Flossenburg on Hitler's direct orders.

Author Ian Colvin, a correspondent of the London News Chronicle, had worked in pre-war Berlin where he made secret contacts with anti-Nazis. He was later expelled from Germany.

After Stauffenberg's July 20, 1944 bomb plot against Hitler, the Canaris group was implicated, arrested and transferred to various concentration camps. In September 1944, incriminating documents were found in the safe of Abwehr officer Werner Schrader following that officer's July 28, 1944 suicide. Later, Canaris' complete personal diary was found in another safe at Zossen. The diaries made clear that Canaris had been playing a double game against the Nazis since before the war, enraging Hitler. On April 9, 1945, Canaris and several other members of the Abwehr resistance circle were put on trial in an SS kangaroo court and were hung at KZ Flossenburg on Hitler's direct orders.

Author Ian Colvin, a correspondent of the London News Chronicle, had worked in pre-war Berlin where he made secret contacts with anti-Nazis. He was later expelled from Germany.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

[ ELEVEN ] — THE VENLOO KIDNAPING

What was there about the flat Dutch landscape that so perturbed Admiral Canaris? He had warned his chosen friends who were conspiring against Hitler that they should not venture into Holland. “I think I have penetrated the British Secret Service,” he had said. “I might receive embarrassing reports from that quarter.”

“Not Holland!” said the friends of Canaris to me in 1938, when we spoke of possible meeting places abroad; but they could not give more precise reasons for their anxiety. As years have passed, the true grounds have become apparent. Agents of all sorts came and went in the Lowlands, and one of them in the late thirties slipped into a position from which he could watch the activities of many others. This was the Dutchman Walbach.

A man was skulking in a quiet avenue of one of the suburbs of The Hague one summer evening, glancing at a pleasant Dutch villa set back from the road. He was there the next day and stumped out of the shadows, hardly taking the precaution to conceal himself. Two men inside the villa watched him and returned from time to time to the windows. He was always there!

On the third day, a man went out of the villa and walked straight up to the stranger.

“If you don’t clear off, I will fetch the police and charge you with loitering!”

“I have no particular wish to loiter here.” The Dutchman Walbach sullenly returned the searching gaze of the German agent. “It’s hardly worth the money that Svert gives me. I have a family to keep.”

“Come inside!”

The loafer Walbach soon found himself in the presence of a short, thickset man with a massive white head and a penetrating stare. The Chief of German counterespionage in Holland, Richard Protze, shook his finger at the Dutchman.

“Don’t you meddle with us, my lad. It will do you no good. What do the others pay you?”

“Seven hundred guilders a month.”

“If you get results, you shall have eight hundred a month from me—and more! Your job will be to work your way into the British Secret Service.”

Walbach, the loafer, stumped off through the Hague, armed with information as bait to catch bigger fish than himself. His activities in the last years of peace and the first months of the war were a nightmare to the Allies up and down the Lowlands, as Allied agents ceased to return from Germany, as operations went awry and secret information leaked out to the enemy. The agent Walbach was always in the shadows of the Dutch landscape, diligent, dissembling, undetected, while his victims walked away to prison and death.

During the war months of 1939, everything in the West seemed peaceful and flat as the landscape. Except for reconnaissances, the French and the British remained quietly behind the Maginot Line. There was no shelling of cities and not much aerial combat. Only at sea the U-boats and cruisers ranged and struck at British shipping. The American newspaper correspondents, who could see both sides, began to say that this was a “phony war.” Some aspects of the war were difficult to explain to onlookers. The British were cautious of using their unmustered strength. There was intense winter activity in the German High Command, with Hitler ordering weather forecasts and astrological reports and pushing ahead with preparations for a general offensive in the West while his generals entreated him to postpone it, at least until the spring.

Reinhard Heydrich was meanwhile unsatisfied with the balance of power in the Reich. He had lost some face over the Fritsch affair when Goering, resplendent in the uniform of a Reich Marshal, had risen in court, overawed Heydrich’s witness, and torn the prosecution case to threads. At the outbreak of war, Hitler had proclaimed himself “first soldier of the Reich” and confided his person to an army bodyguard battalion, led by Major-General Erwin Rommel, instead of relying on the S.S., who had protected him throughout the years of struggle between Party and State. It was only after the mysterious death of General von Fritsch in the field not far from Warsaw that Hitler began to think of an S.S. bodyguard again.

Heydrich had never got to the bottom of the intrigues of the Army in London during 1938. He knew only that some military opponents of the regime had warned the British against Hitler. The Heydrich Security Service had since been extending its activities abroad in the field of surveillance; but Heydrich had found no positive trace of conspiracies against the Reich government. Then his lieutenant, Schellenberg, suggested to him that, if such plots existed and could not be detected, Hitler might equally well be convinced by an invented plot. It would also have a deterrent effect on the generals if what they were contemplating was actually disclosed in another form. So two operations were planned in outline at the Prinz Albrechtstrasse—more or less simultaneously, though not at first directly related to each other.

One was for a mock attempt on the life of the Führer on November 8, 1939, in the Burgerbrau beer cellar in Munich during the reunion of founder members of the Party. The other was to kidnap two of the principal British agents in Western Europe.

The first was fairly easily arranged by means of a convict, just as the sham Polish attack on Gleiwitz had been carried out by German convicts in Polish uniforms, who were either shot on the spot or slaughtered afterward. A Communist named Georg Elser, under long sentence of internment in Dachau, was promised his liberty by S.S. agents if he would construct a hiding place for a time bomb in one of the pillars of the beer cellar, put an infernal machine inside, and then replace the woodwork so as to hide all trace of tampering. As far as the management of the beer cellar was concerned, it would be easy to inform them that a microphone had to be installed in the hall. At any rate the job was done by Georg Elser, who was evidently, like Van der Lubbe (accused of firing the Reichstag building in 1933), a man of subnormal mentality. Captain S. Payne Best, who had snatches of conversation with him in concentration camp, relates his story fully in The Venloo Incident. Elser was afterward given a large sum of foreign currency and offered the chance to escape. The bomb, connected by a wire to a detonating point outside the hall, was exploded about ten minutes after Hitler had left the reunion, and it killed several of the founder members of the Party who were sitting longer and drinking beer together. This lent color to the incident and made it seem more realistic. Elser was “recaptured,” the following day, at the Swiss frontier where he was naively trying to cross without a passport at a customs station.

The business of kidnapping these particular British agents appears to have been a little more difficult, though not much. Heydrich believed that the principal agency of the British Intelligence Service for watching Germany was situated in The Hague. Walbach had by now burrowed deep into the British Intelligence System and asserted that its chief was Major R. H.

Stevens, an official attached to the British Consulate in The Hague. Heydrich took Stevens to be Chief of British Intelligence for northern Germany.

So it came about that, after the Polish campaign was over, the S.S. security officer Schellenberg, who had been watching an agent called Franz—one who went to and fro between Germany and The Hague—used him to carry the idea to Major Stevens and his associate, Captain S. Payne Best, that a group of Army officers plotting against Hitler was anxious to establish contact with the British Secret Service. There was excitement in high Foreign Office circles in London.

Stevens and Best were ordered to probe the offers that might be made on the spot. A cautious game of cat and mouse went on for some time in the flat Dutch landscape, at frontier villages between Arnhem and Venloo. The British agents grew bolder, then careless, and gave a wireless set and a code to Schellenberg, who was posing as an army officer under the pseudonym of Schaemmel, and declaring in solemn secrecy that he was in the confidence of General von Rundstedt.

Lord Halifax was kept informed of the progress made and the British agents were instructed from London not to commit themselves or to make any propositions in writing, but to listen to what might be proposed to them. These two German “emissaries” ^ showed a strange reluctance to venture far over the frontier, though German businessmen were going to The Hague and Amsterdam every day. The ninth of November was the day of evil omen. The Germans came to Venloo to talk, said that their general was on the way to a frontier cafe, the Cafe Backus near Venloo, but they contrived to keep the British so late that Stevens and Best drove to the rendezvous at the cafe without waiting for the Dutch bicycle patrol that was to have been their bodyguard. At the Cafe Backus there was no general and no peace proposals; instead, a car loaded with an armed commando of Germans in plain clothes roared through the neutral area, seized these unfortunate men, and shot the Dutch conducting officer, Captain Dirk Klop, who gallantly drew his pistol and tried to prevent the car from driving off. Within a few seconds, Stevens and Best were riding under heavily armed escort into the Reich.

“Have you a hand in this? Where is Major Stevens?” Canaris fired this question at Richard Protze, whom he had ordered to report to him personally in Düsseldorf.

“Stevens is in Holland,” answered Protze.

“He is not! He is in Germany,” shouted the Admiral. “If you have a hand in this there will be the devil to pay.”

“I know nothing at all about this affair,” replied Protze, quivering with apprehension.

“Ask Abwehr II,” hissed the Admiral, but none of his branches could tell him anything about it.

Protze quickly put his beagle, Walbach, onto the trail in The Hague and received the dry answer from the British, “The Germans know better than we do where Stevens is.”

“Canaris was not informed in advance of the S.D. action at Venloo,” General Lahousen assured me. “Nor were the Commanders in Chief, and they were more than a little perturbed. The Admiral had a horror lest the Gestapo might extort from Stevens and Best something about the opposition in Germany.”

Canaris took soundings with Heydrich as to whether any German intelligence officers were compromised by the affair. Heydrich answered that there were no Abwehr officers involved, but it seemed that the loyalty of some senior generals was questionable.

The German newspapers were full of the details of the “bomb plot” in Munich and, on the following day, of the Venloo kidnapping. Schaemmel, alias Schellenberg, sent one last sarcastic message over the British wireless set and then let it be photographed by the Propaganda Ministry as a piece of evidence. One Professor de Crinis, an S.S. doctor who later became head of the Psychiatric Clinic of the Berlin Charity Hospital, had the brilliant idea of linking the Venloo incident with the Munich beer-cellar “plot” and suggested this to Heydrich. Stevens and Best were paraded where Elser could see them and learn to identify them without hesitation; he was briefed in the second phase of the deception; but although German newspapers asserted that the two British agents were behind the plot on the life of Hitler, details of the two incidents were not entirely easy to reconcile, and eventually the idea of a grand state trial was dropped. Heydrich had nevertheless achieved two stage effects. He had invested his Führer with the aura of a charmed life and recalled the ebbing sympathies of the common people. He had also made it appear that there were traitors in Germany with whom the British wanted to get in touch. He established his case for an S.S. bodyguard beyond all doubt, and Hitler never again confided his person to the Army.

Canaris had meanwhile transferred his political intelligence work, which was a forbidden field for him, to the safer precincts of the Vatican. Dr. Josef Müller, his Roman Catholic friend, had a deep and crafty mind and was a man who could dissemble with almost the artistry of his chief. He was short, paunchy, with the bland face of a bon viveur. Nobody would have believed that this lieutenant of the reserve would quietly carry on negotiations of high treason at a time when the shadow of Heydrich had fallen across their secret contacts with England.

Müller was attached to the Munich office of the Abwehr which worked into Italy. He had an old friend in the Vatican, a German Jesuit from Freiburg in Breisgau, Father Laiber, who was secretary to the Pope. Pope Pius XII himself, as Cardinal Pacelli, had made a particular study of Germany before his election to the throne of St. Peter in March, 1939. He had spent many years in Berlin as Papal Nuncio and had seen the struggle between the pagan Nazis and Mother Church and met the leaders of the German opposition. Müller was given his passports by Canaris’s office and, in the middle of November, was sent off to the Vatican, where he soon made progress. Francis D’Arcy Osborne, the British

Minister, sent home to London for instructions, and permission was given for discussions to be held with Müller on a basis for peace which would be acceptable to both Britain and a Germany that had purged itself of the Nazi regime.

His object, Müller declared, was to work out a draft...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PUBLISHERS NOTE

- [ FOREWORD ] - THE INTELLIGENCE GAME

- [ ONE ] - AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS AMBITION

- [ TWO ] - AN AMOROUS POLISH SPY

- [ THREE ] - THE SPANISH ADVENTURE

- [ FOUR ] - THE RUSSIAN KNOT

- [ FIVE ] - THE ANNEXATION OF AUSTRIA

- [ SIX ] - THE CONSPIRACIES BEGIN

- [ SEVEN ] - CANARIS’S EMISSARY IN LONDON

- [ EIGHT ] - BETWEEN PEACE AND WAR

- [ NINE ] - THE GREAT MOBILIZATION

- [ TEN ] - THE ADMIRAL HELPS A LADY

- [ ELEVEN ] - THE VENLOO KIDNAPING

- [ TWELVE ] - NORWAY

- [ THIRTEEN ] - CANARIS AND THE INVASION OF ENGLAND

- [ FOURTEEN ] - THE ADMIRAL ADVISES FRANCO

- [ FIFTEEN ] - IN THE BALKANS

- [ SIXTEEN ] - HOW THE ADMIRAL GOT HIS BAD NAME

- [ SEVENTEEN ] - EXIT HEYDRICH

- [ EIGHTEEN ] - THE PLASTIC BOMB

- [ NINETEEN ] - ASSASSINATE CHURCHILL!

- [ TWENTY ] - CICERO, THE FAMOUS SPY

- [ TWENTY-ONE ] - CONSTANTINOPLE

- [ TWENTY-TWO ] - CANARIS UNDER SUSPICION

- [ TWENTY-THREE ] - THE ATTEMPT TO KILL HITLER

- [ TWENTY-FOUR ] - THE ADMIRAL IN HIS CELL

- [ TWENTY-FIVE ] - THE POSTMORTEM

- [BIBLIOGRAPHY]

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Master Spy by Ian Colvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.