- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

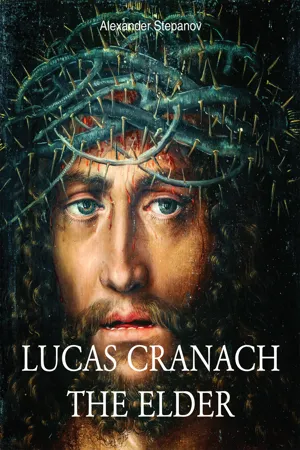

Lucas Cranach the elder

About this book

Lucas Cranach (1472-1553) was one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, as shown by the diversity of his artistic interests as well as his awareness of the social and political events of this time. He developed a number of painting techniques which were afterwards used by several generations of artists. His somewhat mannered style and spending palette are easily recognized in numerous portraits of monarchs, cardinals, courtiers and their ladies, religious reformers, humanists and philosophers. A part of the Great Painters Collection, translated from the Russian by Paul Williams. 109 full color plates and numerous black and white and two-color illustrations interspersed by text. Includes a chronological table of the work of Cranach and his notable contemporaries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art GeneralHis Work

He was capable of conveying shape, motion and character so persuasively that it seems that the artist did not bend the object to his will use his customary devices, but rather the object took possession of the artist. In such pieces there is nothing studied, nothing mannerist, none of the stylistic marks of sixteenth-century art. Each work of this kind is a stunningly powerful burst of everyday life, a short circuit in the line from the object to the artist.

Yet working alongside that Cranach was another artist, entirely different, who is most often perceived as a naive, sensitive provincial striving to be significant, important, refined, but lacking the requisite knowledge, taste and sense of measure, as a result of which his paintings are marred by a confused conglomeration of objects, a primitiveness reminiscent of cheap popular prints, or a mannered dreaminess. Moved to condescension, however, scholars tend to excuse those inadequacies for the sake of the enchanting effects in his brilliant woodcuts and his keen, smooth painting with its elegant, clear, yet flowery palette. It seems to me that Lucas would have laughed sarcastically at any attempt to represent him as some kind of simpleton. The archetypical elements and irregularities in his art that so offend the academically tutored eye are not reflections of inadequate training. They are bold experiments, requiring absolute mastery, brilliantly accomplished tours-de-force employed to create magic mirrors for the Wittenberg elite.

The brothers, Frederick and John, strove to magnify the glory of Electoral Saxony. Court poets pursued that goal with their pens, and Lucas Cranach, almost from the moment he settled in Wittenberg, was expected to busy himself producing woodcuts. Almost every one of those works incorporates two shields: the crossed swords that were Frederick’s badge, and John’s garland of rue.

This was an indication of the artist’s patrons and at the same time a mark of quality: “Made in Saxony.” Sold in their thousands, these prints made the whole of Europe aware of Saxon daring and generosity, Saxon courtesy and enlightenment, and Saxon piety. Who could combine such qualities in himself? The answer was provided by a woodcut depicting a knight who, heedless of the viewer, directs his restive horse towards a goal that only he knows, clasping a commander’s baton in his ironclad right hand. The verse below proclaims:

In Germany, from North to South, A saying springs to every mouth: “When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?”

That is quite true, but it’s certain still:

The nobility sprang up at God’s will.

And we should honour them as their due, the way St Paul taught us to.

And the nobleman should think this way As Emperor Maximilian is wont to say: “I am a man like all the others, Only God has honoured above brothers.”[2]

45. The Virgin and Child under an Apple Tree (detail), 1520-1526. Oil on canvas (transferred from panel), 87 x 59 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

46. The Nymph of the Spring, after 1537. Oil on panel, 48.4 x 72.8 cm. The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

47. Nymph of the Spring at Rest, 1518. Oil on wood, 59 x 91.5 cm. Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig.

48. Nymph of the Spring at Rest, c. 1530-1535. Oil on wood, 77 x 121.5 cm. Collection of Countess Margit Bathyany-Thyssen, Villa Favorita, Lugano-Castagnola.

The knight here is not simply a representative of one of the feudal estates, but the leader of the army of Christ, those whom St. Paul exhorted to gird their loins with truth, to put on the breastplate of righteousness, to take the helmet of salvation and the sword of the spirit, which is the word of God. (Eph. 6: 14-17). Is the initial adorning the horse-cloth not perhaps an indication of the knight’s membership of the Order of St George, a body created for the fight against the Turks and headed by the Holy Roman Emperor? Like the author of the poem, Lucas regarded the noble estate as the best among equals in the Christian world. The heroes of his first Wittenberg woodcuts are those figures who embodied the knightly ideal: the Archangel Michael, St George and the young Roman Marcus, Curtius, who is supposed to have ridden his horse into a chasm which opened up in the forum in order to placate the gods.

In depicting the archangel, Lucas made use of the mediaeval compositional proportions that expressed the striving of Heaven and Earth towards one another; the frame contains two equilateral triangles whose points meet beneath the wheel of the scales. Michael’s outline is threateningly dark against the sky which dominates the ground and is thoroughly permeated with parallels repeating the tipping of the bowls and pointer of the scales in the direction of the saved soul. An invisible thread from the bowl of righteousness seems to deflect the point of the sword and add weight to the blow that falls upon the demons. St George turns to God, symbolized by the cross on the banner, to express gratitude for his victory over the dragon. The details of the princess’s rescue distract one from the delicate figure of the saint. The inspired face stands out all the stronger, leaving no doubt that a victory over evil can only be obtained through the power of faith.

In order to bind the large-headed, puny victor more closely to the Earth, Lucas gives him a vertical support and places him in a broad frame, so that the figures occupies the middle one of three equal sections marked out at the top by the concave segments of the shields. The Ancient Rome saved by Marcus Curtius is, in the Germanized fantasy of a North European artist, a realm of light, order and harmony. This is already evident in the balanced, easy relationship between the sides of the print and the diagonal of the square to its side, marked by the edge of the terrace.

The pavilion divides the space up into three equal parts. Symmetrical groups leave a clear area in which the sky and the ground join without encroaching on one another. Marcus’s fellow countrymen are reserved, as befits Romans. Only one, unable to stand the tension, is stirring. His gaze fastens on the birds which promise fulfilment of the prediction made by the auger standing to the right of the horseman plunging into the underworld. The hero’s helmet is adorned by the winged dragon. Three passions obsessed the true knight: single combat, hunting and love. All three held an important place in Cranach’s work from his first years of service under Frederick.

All Saints’ Day (November 1st) was the main festival for the university church, and was marked by the display of its extremely rich collection of relics which were supposed to grant those who saw them forgiveness of their sins. Following the religious festival, each year the noble masters of Wittenberg and their guests arranged knightly tournaments accompanied by banqueting and dancing. People poured into the city to witness these spectacles in which the elector was an enthusiastic participant.[3] His court artist recorded them in woodcuts. It is not easy to work out what is going on in these works. One has to scan the large sheets, concentrating on one participant at a time and following the direction of the lances.

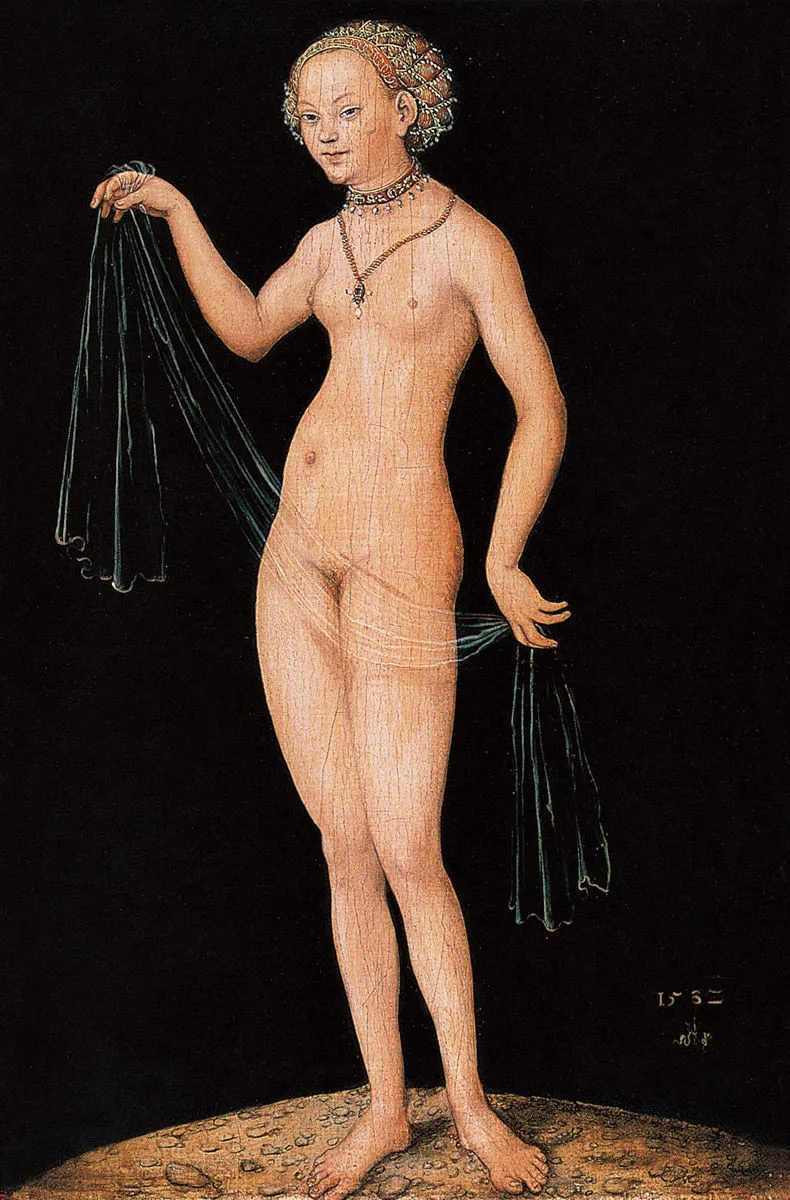

49. Venus, 1532. Tempera and oil on beech, 37 x 25 cm. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main.

50. The Garden of Eden, 1530. Oil on wood, 81 x 114 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

51. The Faun and his Family, 1531. Oil on wood, 44 x 34 cm. Private collection.

52. Adam and Eve, c. 1510. Oil on limewood, 59 x 44 cm. Museum Narodowe, Warsaw.

One ceases to notice the frame until one suddenly comes upon it by the left or right-hand group of knights before plunging back into the fray. The sense of being there is overwhelming and must have been stronger still for Cranach’s contemporaries who would have been able to recognize individual knights by their badges or the decoration of their saddle-cloths. In the first of these prints, in which the public is allotted as much attention as the combatants, Lucas assumes the role of an observant and amusing narrator.

There are here fourteen knights, twenty-two mounted armour-bearers and servants, another seventeen on foot, and nine musicians on horseback, and among the spectators five dogs, nine children, ten horsemen and some six dozen common people, not counting the...

Table of contents

- His Life

- His Work

- Biography

- Index

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lucas Cranach the elder by Alexander Stepanov in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.