Veterinary Clinical Skills

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Veterinary Clinical Skills

About this book

Provides instructors and students with clear guidance on best practices for clinical skills education

Veterinary Clinical Skills provides practical guidance on learning, teaching, and assessing essential clinical skills, techniques, and procedures in both educational and workplace environments. Thorough yet concise, this evidence-based resource features sample assessments, simple models for use in teaching, and numerous examples demonstrating the real-world application of key principles and evidence-based approaches.

Organized into nine chapters, the text explains what constitutes a clinical skill, explains the core clinical skills in veterinary education and how these skills are taught and practiced, describes assessment methods and preparation strategies, and more. Contributions from expert authors emphasize best practices while providing insights into the clinical skills that are needed to succeed in veterinary practice. Presenting well-defined guidelines for the best way to acquire and assess veterinary skills, this much-needed resource:

- Describes how to design and implement a clinical skills curriculum

- Identifies a range of skills vital to successful clinical practice

- Provides advice on how to use peer teaching and other available resources

- Covers veterinary OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) topics, including gowning and gloving, canine physical examination, and anesthetic machine setup and leak testing

- Includes sample models for endotracheal intubation, dental scaling, silicone skin suturing, surgical prep, and others

Emphasizing the importance of clinical skills in both veterinary curricula and in practice, Veterinary Clinical Skills is a valuable reference and guide for veterinary school and continuing education instructors and learners of all experience levels.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

What Is a Clinical Skill?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- About the Companion Website

- 1 What Is a Clinical Skill?

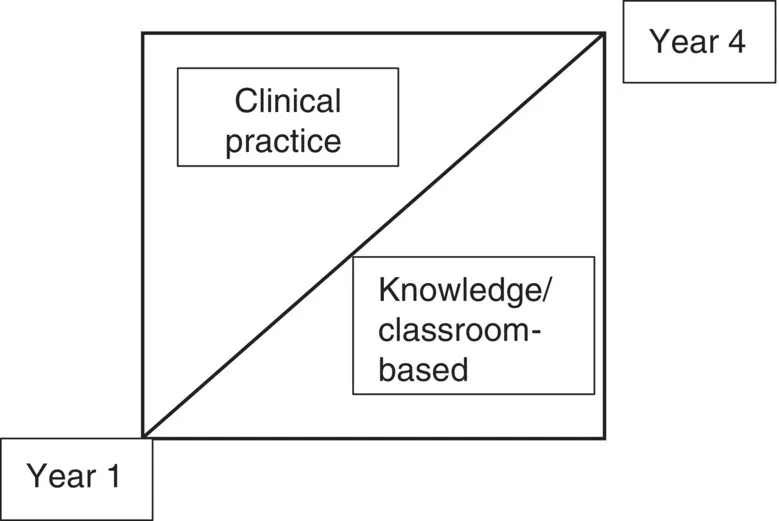

- 2 Clinical Skills Curricula: How Are They Determined, Designed, and Implemented?

- 3 How Are Clinical Skills Taught?

- 4 How Are Clinical Skills Practiced?

- 5 How Do I Know if I am Learning What I Need to?

- 6 How Do I Prepare for Assessment and How Do I Know I Am Being Assessed Fairly?

- 7 How Can I Best Learn in a Simulated Environment?

- 8 How Do I Make Use of Peer Teaching?

- 9 What Other Skills Are Vital to Successful Clinical Practice?

- Appendix 1: OSCEs (Objective Structured Clinical Examinations)

- Appendix 2: Recipes for Making Clinical Skills Models

- Index

- End User License Agreement