![]()

1

DEEPENING THE LAYERS OF UNDERSTANDING AND CONNECTION

A Critical-Dialogic Approach to Facilitating Intergroup Dialogues

Biren (Ratnesh) A. Nagda and Kelly E. Maxwell

Intergroup dialogue has emerged as an educational and community-building approach that brings together members of diverse social and cultural identities to engage in learning together—sharing and listening to each other’s perspectives and stories and exploring inequalities and community issues that affect them all, albeit differently—so that they may work collectively and individually to promote greater diversity, equality, and justice (McCoy & Scully, 2002; Schoem & Hurtado, 2001; Walsh, 2007; Zúñiga, Nagda, Chesler, & Cytron-Walker, 2007). Be it involving middle or high school students, college students or community constituents, intergroup dialogue provides a structured, supportive, and sustained environment in which participants can grapple with issues and questions that may otherwise remain taboo and divisive (Tatum, 1997). Issues as broad and intractable as racism, sexism, and classism or as specific as racial health disparities, violence against women, immigration, abortion, gay marriage, and racial profiling may remain silent because of fear and a lack of structured opportunities for people to engage across lines of differences in perspectives, experiences, and identities. Discussing these issues may also be taboo for questioning and challenging established norms and practices, for maintaining a social order that privileges some groups over others, or for the personal shame and guilt that the issues evoke. Not only may we feel constrained in saying what we may be thinking, but also we often do not hear others clearly because of what we are thinking (Warner, 2009). With increasing social diversity in workplaces, communities, and educational institutions, some advocate for ignoring social identities and differences, while others advocate for embracing a multicultural perspective that recognizes differences in power and privilege. Both sides may be emboldened by their concerns for fairness and equality, yet they seem oppositional in the ways that they actualize the paths and means to justice.

But these differing perspectives and the parties holding these perspectives do not engage authentically in a public setting. Personal concerns remain separated from group-based analyses and private deliberations remain disconnected from public discourse. Intergroup dialogue intervenes in these spaces of estrangement that both reinforce and are reinforced by the ignorance, silence, or cautious discourse. It seeks to be a medium for transformative engagement that can change contentious arguments into productive dialogues. It engages participants to create ways of understanding, living, and working together that are more equal and just. It seeks to unearth barriers in thinking, feeling, and relating so that there is both a better understanding of inequalities, differences, and conflicts that divide and a stronger foundation for building bridges that may help members of different groups across separations and disconnections. Even when intergroup dialogue may not lead directly to change, it can help create the conditions to catalyze greater community collaboration among previously estranged groups.

Focus of This Book

This book, therefore, seeks to extend our understanding and knowledge of intergroup dialogue practice with a focus on intergroup dialogue facilitation. Intergroup dialogue is a co-facilitated learning endeavor that brings together members of two or more social identity groups to build relationships across cultural and power differences, to raise consciousness of inequalities, to explore the similarities and differences in experiences across identity groups, and to strengthen individual and collective capacities to promote social justice. With guidance from trained co-facilitators, dialogue groups of about 12–16 participants, meet weekly over a period of 10–14 weeks. Co-facilitators, representing the groups that are in dialogue, provide balanced leadership for the learning process. They use an educational curriculum that integrates multiple dimensions of learning: content and process learning; intellectual and affective engagement; individual reflection and group dialogue; individual, intergroup, and institutional analyses; and individual and collective actions (see Zúñiga et al., 2007, for a detailed description).

Despite a growing number of books and articles in professional journals and magazines focusing on intergroup dialogue, there remains a dearth of writing and in-depth understanding of intergroup dialogue facilitation. Other than chapters in books or a brief mention within other chapters, little has been written specifically about intergroup dialogue facilitation (see Beale, Thompson, & Chesler, 2001; Nagda, Zúñiga, & Sevig, 1995; Zúñiga et al., 2007) or facilitating social justice education courses or workshops (see Burke, Geronimo, Martin, Thomas, & Wall, 2002; and Griffin & Ouellett, 2007, for exceptions). In this book, the first dedicated entirely to intergroup dialogue facilitation, we draw on our joint practice and research knowledge to define the facilitation role in greater detail, articulate the broad and specific foci of training and supporting facilitators, and share emerging research on intergroup dialogue facilitators with implications for practice. Many of the contributing authors have worked in higher education settings as well as collaborated with community organizations and youth in K–12 schools. We bring insights gained from these experiences to contribute to the overall knowledge and practice base of dialogue in a variety of contexts.

In this introductory chapter, we focus on our experiences with a particular kind of intergroup dialogue—the critical-dialogic model of intergroup dialogue that is now being used at many different U.S. colleges and universities. Rather than only discussing facilitation training and multicultural competencies, as others have done previously (see Beale et al., 2001; and Zúñiga et al., 2007), we seek to connect intergroup dialogue facilitation to the unique, transformative potential of intergroup dialogue and the underlying processes of change in intergroup dialogue.

Intergroup Dialogue: Critical-Dialogic Engagement and Facilitation

We lay a foundation here for understanding the importance and uniqueness of intergroup dialogue facilitation. We elaborate on facilitation within a critical-dialogic model of intergroup dialogue, an interdisciplinary model informed by the fields of multicultural and social justice education, intergroup contact and intergroup relations, and communication and conflict studies.

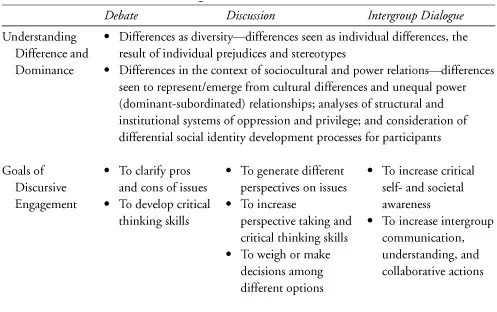

Discursive Engagement With and Across Differences

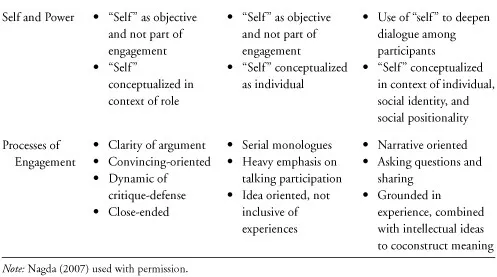

Table 1.1 shows a critical-dialogic model of intergroup dialogue in the context of other models of discursive engagement such as debate and discussion that are also concerned with teaching and learning about differences and diversity. The framework shows the unique ways in which intergroup dialogue works with the dimensions of participatory learning about and across differences and sets the stage for understanding intergroup dialogue facilitation within this model (see also Nagda & Gurin, 2007). We refer to our model of intergroup dialogue as a critical-dialogic approach to differentiate it from approaches that only build relationships among participants without an explicit recognition of differences, and models that focus on raising consciousness to lead to action but do not deal fully with the complexity of relationships among the participants.

TABLE 1.1

Approaches to discursive engagement with and across differences

(Nagda & Gurin, 2007)

The dialogic goals of intergroup dialogue are aimed at building affective self–other relationships through personal storytelling and sharing, empathic listening, and interpersonal inquiry (Kim & Kim, 2008;Young, 1997). Dialogue seeks understanding across differences through connected knowing rather than an imposition of a singular perspective (as in debate) or serial monologues (as in discussion) (see chapter 8 for further distinction between debate and deliberation). Dialogue, in a critical-dialogic approach, seeks not only an understanding of one’s own and others’ perspectives on issues, but also an appreciation of life experiences that inform those perspectives. Participants learn to listen to others, share their own perspectives and experiences, reflect on their learning, and ask questions to more fully explore differences and commonalities within and across social identity groups.

The critical goals of intergroup dialogue are centered on understanding how power, privilege, and group-based inequalities structure individual and group life as well as on fostering individual and collective responsibilities for redressing inequalities and promoting social justice (Delgado & Stefancic, 2000;Freire, 1970). Dialogues across differences do not happen in a vacuum; intergroup dialogue is centrally concerned with issues of power and privilege and their effects on personal and social identities. Intergroup dialogue takes a critical understanding of difference, one that conceptualizes difference in the context of dominant-subordinated relationships and not simply as diversity (McMahon, 2003). In the intergroup context with participants from privileged and less-advantaged groups (such as people of color and White people, or women and men), participants usually hold different understandings and experiences of identities and inequalities (Tatum, 1997). Thus, we extend the basis of dialogue to intergroup dialogue; that is, we bring a critical perspective to dialogue.

Jointly, the critical-dialogic goals seek to mobilize the power of cross-group relationships not only as a focal point of analysis of structural inequalities and the consequences on group and individual lives, but also as sites for relating in ways that advance individual and collective agency for transformative social change (Nagda, 2006; Saunders, 1999). Through sharing, listening, and inquiry, we aim to explore the commonalities and differences in experiences. Oftentimes, these narratives are grounded in identities, privilege, and/or social exclusion. We aim to gain a deeper understanding not only of our personal biographies but also of the contextual situations and structures that affect us similarly and differentially. Within such a critical-dialogic approach, community building and conflict exploration are not oppositional; rather, they are important processes toward greater social justice through acknowledging and recognizing inequalities, structuring opportunities for greater access and participation in social institutions, reforming relationships, and exploring sustainable redistribution of power.

Emerging research on intergroup dialogue, directly on facilitation and indirectly on what the facilitators create, leads to three conclusions. First, simply, facilitation matters! Facilitation and structured interaction in intergroup dialogue has been found to be more favorably effective in learning compared to traditional lecture/discussion methods (Nagda, Gurin, Sorensen, & Coombes, 2009). Second, psychological processes fostered in intergroup dialogues are important because people’s individual experiences and internal change, both cognitive and affective, are related to positive outcomes (Nagda, Kim, & Truelove, 2004; Stephan, 2008). Third, four communication processes characterize intergroup dialogue (Nagda, 2006):

1. Appreciating difference involves an openness to learn from others through intentional listening, asking questions, and appreciating life experiences and perspectives different from one’s own.

2. Engaging self speaks to active involvement of participants in intergroup interactions characterized by personal sharing, voicing disagreements, and addressing difficult issues.

3. Critical reflection involves students examining and understanding their own perspectives and experiences, and those of other students in the dialogue, through the lenses of privilege and inequality.

4. Alliance building is defined as a process that involves both talking about ways to collaborate on action to work against injustices and bring about change, and strengthening the relationship by working through disagreements and conflicts (Nagda, 2006).

Psychological and communication processes are intimately related to the work of the facilitators. We discuss the facilitation principles involved in dialogue across differences with facilitators as guides who themselves are intimately connected to the learning process and who are committed to fostering critical-dialogic communication processes among participants.

Facilitation Principles in Discursive Engagement With and Across Difference

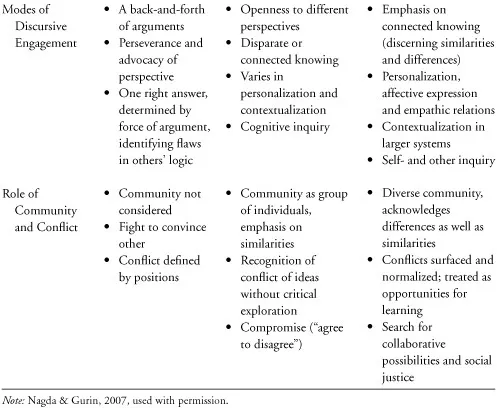

Like intergroup dialogue itself, intergroup dialogue facilitation is a distinct and principled approach to guiding engagement with issues of social justice that bridges the personal and the political, connects reflection and dialogue, and mobilizes relationships for collaborative action. Table 1.2 expands on Table 1.1 with an explicit focus on facilitation. In the following sections we discuss three major principles that inform intergroup dialogue facilitation.

Principle 1: Guiding, Not Just Teaching

Intergroup dialogue facilitation is mindful, responsive, and responsible guidance, not formalized teaching or instruction. Participants in dialogue are not passive receptacles to be filled with the facilitators’ knowledge, but are themselves educators of their own experiences and understandings of social reality. Whereas in debates or discussions the facilitator referees or directs the instruction and interactions, intergroup dialogue facilitators pay keen attention to the conjoint learner–educator roles that every participant plays. A mode of facilitators as guides rather than facilitators as teachers allows them to partner with students to create a joint learning experience (see chapter 6). The emphasis on guiding learning through reflection, dialogue, and action does not mean laissez-faire facilitation, but an intentionality to create an inclusive learning environment that can foster meaningful engagement.

Creating an Inclusive Space for Differences and Dialogue

Because intergroup dialogues bring together equal numbers of participants from the different groups in dialogue—usually groups situated in dominant-subordinated power relations—facilitators work to create an inclusive learning space that can hold divergent and convergent experiences and perspectives. Intergroup dialogues use intentional pedagogy that builds appreciation for and understanding of differences that are often connected to participants’ identities and positionalities. In discussions or debates, the group composition is not necessarily structured with social identities in mind, nor is there explicit attention to engaging with identities. Differences may be conceived of as simply about perspectives and information that are open to being challenged. Or, they may be acknowledged as related to group-based experiences in the larger society but engaged with only abstractly or theoretically. Views and perspectives may or may not be personalized by individual participants. Within the ground rules for dialogue, particular attention is paid to how participants and facilitators work to hold the differences and see them as enriching and not undermining the learning. Yeakley (chapter 2) provides helpful suggestions on how to create a foundation for an inclusive climate.

TABLE 1.2

Facilitator roles in discursive engagement with and across differences

Co-facilitation

Intergroup dialogue uses a co-facilitation approach, not solo facilitation, and embraces alliance building at the heart of its relationship. Intergroup dialogue facilitators share power with each other and with members of the dialogue group in ways that make the best use of everyone’s aspirations, skills, and abilities. For group participants, the co-facilitation model ensures, as much as possible, representation and support in the facilitative leadership. Co-facilitators are not neutral or impartial but multipartial and balanced as a team in supporting all group members (see chapter 3). Co-facilitators can support and challenge participants from their own identity groups empathically and, at the same time, model for participants ways of connecting across social boundaries. The co-facilitation alliance provides facilitators a site for enacting and modeling their commitments to intergroup collaboration, mutually beneficial learning, and a shared project to advance the learning of others (see chapters 4, 5, and 12).

Integrating Content and Process

Obviously, facilitators bring immense commitment and passion to their work in addition to the knowledge, awareness, and sk...