![]()

PART ONE

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

ON SOCIAL JUSTICE

EDUCATION

![]()

1

A SOCIAL JUSTICE EDUCATION

FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

FRAMEWORK FOR A

POST-GRUTTER ERA

Maurianne Adams and Barbara J. Love

The June 2003 Supreme Court finding for Grutter v. Bollinger et al. permitted postsecondary admissions policies to include race and ethnicity as narrowly tailored “plus” factors in efforts to increase campus social and cultural diversity. However, in affirming the educational benefits of diversity, the role of this Court’s majority decision goes beyond permitting admissions policies to be tailored toward campus diversity. The Court reiterated its view, established in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that “education … is the very foundation of good citizenship” and that “effective participation by members of all racial and ethnic groups in the civic life of our Nation is essential if the dream of one Nation, indivisible, is to be realized” (Grutter v. Bollinger et al., 2003, pp. 331–332). It also affirmed expert testimony concerning the educational benefits of diversity: namely, promoting cross-racial understanding, breaking down racial stereotypes, enabling students to better understand cross-racial differences, and providing classrooms that are “livelier, more spirited, and simply more enlightening and interesting” based on “the greatest possible variety of [student] backgrounds” (p. 330, referring to Bowen & Bok, 1998; Orfield & Kurlaender, 2001). The Court affirmed the “overriding importance” of diversity in higher education in “preparing students for work and citizenship” and in “sustaining our political and cultural heritage” (Grutter v. Bollinger et al., 2003, p. 331).

This decision is heartening for faculty and administrators who have long sought to enhance both the presence and role of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups on predominantly White college campuses and to facilitate their interaction with traditionally privileged social groups. It affirms a line of reasoning and evidence that all students benefit from thoughtfully designed, socially diverse instructional settings. The research cited by the Grutter (2003) Court goes beyond the merely physical desegregation affirmed by the Brown (1954) Court and links the benefits of diversity to programs of study that facilitate productive and long-term relationships across social and cultural differences (Chang, 2005; Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, & Gurin, 2002; Nagda, Gurin, & Lopez, 2003; see also Milem, 2003, and Zúñiga, Nagda, Chesler, & Cytron-Walker, 2007).

The substantial research cited in support of the Grutter ruling is part of a larger tradition of research on the benefits to all students of social and cultural diversity in higher education reaching back to the 1950s and school desegregation in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. This research tradition disconfirms the naïve belief that merely admitting students from previously underrepresented racial and ethnic groups will in itself be educationally and socially salutary. Instead, it documents specific conditions that must be met if intergroup contact is to become educationally beneficial. Known collectively as the “contact hypothesis,” these conditions include equal group status within educational settings, shared educational goals, intergroup cooperation, opportunities for sustained rather than incidental or random intergroup interactions, and the support of institutional authorities for the educational benefits of social diversity (Allport, 1954; Brewer & Brown, 1998; Brown, 1995; Pettigrew, 1998).

Following desegregation in the late 1950s and the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, colleges and universities have developed core requirements that not only address issues of diversity but foster interaction among multiple perspectives (Humphreys, 2000). Faculty have designed undergraduate courses and curricula on diversity and social justice in which the curricular content, the course pedagogy, and the students who enroll make possible the civic and educational benefits of diversity described here. Faculty and campus administrators have understood that beyond the moral, demographic, and political rationales for increasing access to higher education for students from underrepresented social groups, there are compelling educational reasons to rethink the curriculum and pedagogy to assure reciprocal benefits for all participants within these demographic changes (Adams, 1992; Chang, 2000/2001; Clayton-Petersen, Parker, Smith, Moreno, & Teraguchi, 2007; Milem, 2003). The body of empirical research and curricular writing that builds on the benefits of diversity, multiculturalism, and social justice in higher education is large and growing, providing valuable resources for faculty and administrators who are working toward social and cultural equity and inclusivity at the level of interactions, whether between individual students or within classrooms, disciplinary curricula, and entire postsecondary institutions (most recently, see Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007; Bauman, Bustillos, Bensimon, Brown, & Bartee, 2005; Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005; Ouellett, 2005; Williams, Berger, & McClendon, 2005).

The implications of this literature are challenging for faculty, most of whom have been trained in lecture-mainly classes or discussion sections within relatively homogeneous classrooms. For many, the knowledge and skills necessary for effective undergraduate teaching were not core components of their doctoral preparation and professional apprenticeship. Instead, many faculty, at four-year institutions as well as community colleges, teach in ways that reproduce their own successful academic experiences as products of demographically homogeneous campuses. It is not surprising that such faculty may be ill prepared to teach in classrooms populated by students whose backgrounds, culture, educational socialization, and birth-languages may differ from theirs.

The National Center for Education Statistics documents the widening demographic gap between the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of students in higher education (from 15%in 1976 to 30%in 2004) and the relative homogeneity of the faculty (e.g., faculty from underrepresented groups at 15% in 2003) (NCES, 2006). To better prepare traditionally trained faculty for demographic and cultural changes in their classrooms, many campuses have created centers for teaching, offices for diversity, and graduate programs that offer inclusive teaching opportunities in diverse classrooms. This is the larger national context for the social justice education approach presented in this chapter.

A Social Justice Education Framework

Our social justice education perspective is based on an analysis of the processes of schooling that reproduce overarching societal structures of domination and subordination. By this we mean that schooling often reproduces patterns of social and economic inequality that have historical roots and that characterize contemporary society. These patterns of inequality are based on social and cultural differences, used as explanations and justifications for the domination of some social groups and the subordination of others. In our view, social and cultural differences often are used to rationalize and justify inequality that, in our view, results not from these differences but from the domination and subordination that are based on and shape those differences. The social justice framework includes an analysis of domination and subordination at different societal, institutional, and interpersonal levels. It includes an analysis of the ways in which structures of domination and subordination are reproduced in the classroom, following patterns of social and cultural difference in the larger society.

A social justice education framework recognizes that the patterns of domination and subordination are manifest throughout and across social institutions. Among these institutions, education plays the dual role of reflecting these stratified relationships as well as reproducing them through access to curriculum as well as course content and pedagogy. But education also offers a unique opportunity for interrupting these unequal relationships, both by helping people understand social inequality and by modeling equitable relationships in the classroom (for further discussion, see Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007).

As social justice educators, we start from the understanding that schooling presents educators with choices, either to ignore and reproduce unequal social relationships or to recognize, interrupt, and transform those relationships. These choices are reflected not only in access to schools and curricula but also in course content and pedagogy. As students in different disciplines learn new course content, they also learn to prize certain knowledge and devalue other knowledge or ignore it entirely. Thus, a social justice perspective on course content enables us to scrutinize a curriculum in order to see the implicit judgments about social relationships embodied by what is included in or excluded from the curriculum.

Similarly, a social justice perspective enables us to recognize the patterns of domination and subordination that characterize the larger society and thus are reproduced in teacher-student or student-student relationships, as well as opportunities to develop reciprocal and equitable relationships. This perspective explores the reproductions of race, gender, class, and other identity-based power inequities and analyzes these in the context of other power relations in the classroom. Such an analysis enables us instructors to clarify the specific kinds of relationships we choose to model and endorse in the classroom.

We share this social justice education framework with our faculty colleagues not because we expect them to include it explicitly in their curriculum, but because we want to convey our view that potentially every component of teaching and learning can be informed by this social justice perspective. We are not asking our colleagues to teach social justice content. Rather, we are asking that our colleagues develop a social justice analysis of their own teaching practice.

A Four-Quadrant Analysis of Teaching and Learning

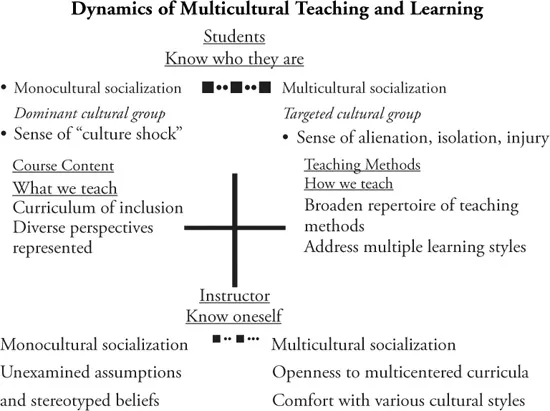

Teaching and learning are fluid, interactive processes that can be characterized in many different ways. To compress our social justice framework into a single heuristic, we conceptualize teaching and learning processes as falling into four interactive quadrants, each one of which can be analyzed from a social justice perspective. These four quadrants are based on (1) what our students, as active participants, bring to the classroom, (2) what we as instructors bring to the classroom, (3) the curriculum, materials, and resources we convey to students as essential course content, and (4) the pedagogical processes we design and facilitate and through which the course content is delivered (Adams & Love, 2005; Marchesani & Adams, 1992). Appendix 1.A provides a worksheet that accompanies the model (Figure 1.1).

As an overall organizer, this model enables us to take snapshots (i.e., our students, ourselves, our subject matter, our pedagogical process) of an extraordinarily complex moving picture which, in real life in the classroom, is a dynamic process by which each quadrant interacts simultaneously with the others. Focusing on each quadrant individually cannot itself reveal the complex interplay among and within these dimensions as they occur in real-time classroom interaction, but it does enable us to consider the characteristics of each quadrant before setting them back into dynamic interaction. The use of this teaching and learning model reflects both our need for order and our recognition of the complexity of the multiple and layered dynamics of teaching and learning.

FIGURE 1.1

Dynamics of Multicultural Teaching and Learning

Quadrant 1: What Our Students as Active Participants Bring to the Classroom

In our experience with faculty colleagues, we find they prefer to begin the conversation with stories about their students rather than about themselves. Focusing on our students is often the way we talk with each other about the challenges and opportunities in our teaching, and starting at this point helps us examine our assumptions and, perhaps, misconceptions about our students, especially when their visible social identities differ from the visible social identities of the faculty. We encourage faculty to focus on dynamic interactions with all students, to notice whether those interactions differ with students who hold different social identities.

Faculty may describe classroom situations in which students interact or fail to interact with each other on the basis of their social identities and the stereotyped expectations that attach to those social identities. The scenarios described by one faculty member may be familiar to others. For example, students assembled in small groups for projects may reproduce the patterns of residential separation along racial or class lines that occur in their hometowns and neighborhoods. In small groups, women may take notes while men speak and take up greater physical and psychological space. Women may appear less comfortable challenging the authority of the teacher; the same may appear with students of color or international students. Male faculty may describe feeling more comfortable with challenges from White male students than from Black men or from women. These situations often refer forward to Quadrant 2, in which we ask faculty to explore their own socialization and their unexamined assumptions about the “other,” who, in this case, might well be their students.

Before doing so, however—especially if we are working in seminars with faculty who appear uncertain how to interpret and deal with classroom scenarios such as these, and who may belong to social groups that have traditionally had the dominant role in higher education—we might use one or more of the following questions to probe faculty analysis of who their students are and what their students bring to the classroom:

• Can you give examples of possible student-to-student interactions (or avoidance) based on their social identities?

• What have you noticed about and how have you accounted for differences in ways that students of different or the same social identities may understand their own and each other’s ways of communicating?

• What differences have you as faculty noticed in students’ differing cultural and individual learning styles and communication and interaction styles?

• What happens when you ask students to reflect on their differing perspectives or their interactions on “hot button” social issues?

• What strategies do you utilize to plan for different levels of skill in, readiness for, and comfort with the subject matter in your classes?

In faculty seminars in which “knowing one’s students” remains the primary or exclusive focus for discussion and analysis, we introduce various organizers to engage faculty with considerations such as learning style and/ or cognitive and social identity development (Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007, chapter 17; Anderson & Adams, 1992). Learning style models help faculty to design a range of learning environments that match some preferred cultural or individual student learning styles while at the same time stretching others. Cognitive development models help faculty to understand the different levels of complexity with which students take in and process knowledge and to anticipate the tendency of some students to dichotomize complex questions, reducing multiple perspectives to simple either/or, right/wrong choices, although other students (often in the same classroom) work with the inherent messiness of real-world social issues and appreciate the multiple, differing perspectives held by their peers (Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007, chapter 17; King & Shuford, 1996; for application, see Adams & Marchesani, 1997). Social identity models enable faculty to understand and account for the possibility that students connected by seemingly same social identities may express very different responses (e.g., denial, anger, pain) to social issues in the classroom (Adams & Marchesani, 1997; Hardiman & Jackson, 1992; Wijeyesinghe & Jackson, 2001). Information about social identities is not important only to the instructor. It is also important for students to know about each other’s social identities, as well as about their own, as a context for understanding their different perspectives on social justice issues.

Quadrant 2: What We as Instructors Bring to the Classroom

We believe that the teacher (i.e., professor, instructor, facilitator, mentor, and/or coach) is an integral contributor to classroom dynamics and not, as in more traditional accounts of teaching and learning, separate from considerations of subject matter and pedagogy, or from teacher-student interactions. Faculty enter the profession with knowledge and skills developed in a range of academic disciplines. This academic-discipline-based knowledge and skill, although obviously necessary for successful classroom teaching, is not sufficient for what we refer to as a social justice education perspec...