![]()

1 Violence in the Shadow of the Ivory Tower

Murder at the University

Richard J. Ferraro and Blanche McHugh

IN THE American imagination, the ideal university (henceforth understood to include universities and colleges) is an institution of social harmony built on charitable foundations that works to enhance the intellectual abilities and professional capabilities of all members of a collaborative academic community. A prerequisite for the fulfillment of this ideal is relative nonviolence: The university must offer a modicum of good order, social stability, and reasoned behavior if it is to deal effectively with teaching, research, and service delivered by a diverse population in a plethora of fields and courses of study.

The University as a Safe Haven

This functional ideal is lent support by a familial ideal. When parents send their sons and daughters to a university, they imagine the destination is a safe haven. They expect their offspring will have a positive and mostly pleasant experience at the minimum, or at the maximum even fundamentally transform themselves personally and professionally after 4 years. Further, they anticipate that occasional stresses and setbacks will be offset by general happiness and broad accomplishments. This is why many parents say they entrust their sons and daughters to a university, even though there are no real legal or contractual bases for defining students as objects accepted in trust.

These functional and familial ideals can be intruded upon by social offenses (such as abuse of alcohol), economic challenges (e.g., significant cuts in external support or overreliance on consumerist models), biased expression (e.g., epithets or stereotyping), and so on. However, the university is most challenged when it comes to murder, literally, for murder potentially transforms the university from a nursery for hope and promising young leaders into a graveyard of despair and lost youth, for people affected directly and for those touched by it.

For many, a university is much safer than the real world. Campus murder rates are indeed lower than they are in the general population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). However, this accurate comparative point is of small comfort when it comes to functional and familial ideals, since expectations for the university are much higher than those that apply to other institutions such as a town, workplace, or corporation. The university, for better or worse, is expected to be—and needs to be—an institution especially committed to life and safety.

Single and Double Murders: Clery and Beyond Clery

It is not easy to obtain an accurate count of all members of the university (students, faculty, and staff) who have been the object of murder. To get a rough preliminary indication, one logically begins by reviewing statistics from the Jean Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act (1992; henceforth referred to as the Clery Act) that track criminal activity including homicide on campuses and in the immediate bordering areas (Security on Campus, 2009).

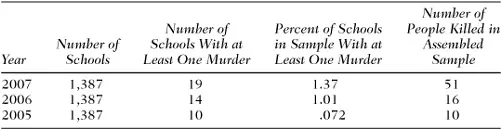

A global overview of pertinent murder statistics can be obtained by using summary findings reported by the U.S. Department of Education (2007) for the years 2005–2007, a 3-year period of systematic collection, aggregation, and gross reporting of data in keeping with the ongoing development of Clery Act regulations and practices. (Such systematic data collection, aggregation, and reporting is not available for years prior to 2005; statistics for 2008 were not available when this book went to press.)

For 2005, 28 murder victims were reported for the several thousand postsecondary institutions that provided information under the Clery Act (including public and private, profit and nonprofit, religious and secular, 2-year and 4-year, graduate and undergraduate, professional and nonprofessional colleges and universities). For 2006, for the same group of schools, the number declined to 25 victims; for 2007 the number jumped to 64, but that large increase is mostly explained by 32 murders in April of that year at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). From these data, it is reasonable to assert that a fraction of 1% of postsecondary schools in the United States experienced a murder in any 1 of the 3 years in question (U.S. Department of Education, 2007).

One might wonder if that relatively small percentage for homicide is made still more compact by the inclusion of 2-year schools and proprietary 4-year institutions. It could be argued that such schools—which on average may have a smaller residential presence, more compact physical plants, shorter hours of attendance on campus, and more nontraditional students—may also have significantly fewer risk factors for homicide in Clery Act terms, and thus may disproportionately reduce the overall average. To test that possibility, the U.S. Department of Education (2007) compiled a list of 1,387 four-year nonprofit colleges and universities. It included large and small, public and private institutions, drawn from all 50 states. For the years 2005, 2006, and 2007, complete entries were obtained for all 1,387 schools (see Table 1.1).

Clery Act data for this broad sample of 4-year, nonprofit schools, still indicate a relatively safe picture. For any year in this 3-year period, 98% to 99% of universities and colleges reported no homicides. There is an increase over an admittedly narrow 3-year time span, as the number of affected schools rises slightly from .072% to 1.37%, and the jump from 10 to 16 to 51 dead from 2005 to 2007 seems quite alarming. However, as noted previously, much of that increase in 2007 is accounted for by one extraordinary incident, that is, the mass slayings at Virginia Tech in April. In the vast majority of cases where homicide occurred over this 3-year period, one or two people were killed per incident.

Table 1.1 Homicides on Campus, 2005, 2006, 2007

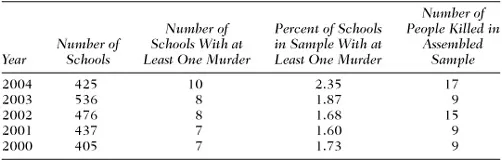

Moving farther back to the years 2000 through 2004 for this same sample of 1,387 colleges and universities, more fragmentary data were reported (see Table 1.2).

The difference between Table 1.1 (1,387 entries) and Table 1.2 (405–536 entries), and specifically the slight increase in the frequency of schools affected by murder, can likely be accounted for by the fact that Table 1.2 includes proportionally fewer small schools. Still, on this narrower sample, the range of 1.6% to 2.35% means that about 97% to 98% of universities and colleges would be spared even a single reported homicide on campus or in the immediately adjacent area in any particular year of this 5-year period.

However, Clery Act statistics do draw a narrow circumference, touching only the campus and immediately adjacent property. In truth, when it comes to the safety of university faculty, staff, and especially students, there really are three pertinent geographical loci: (a) the campus with its buildings, grounds, and immediately adjacent environs; (b) the larger hinterland, consisting of the greater neighborhood and nearby town, city, or county; and (c) more remote locations, such as a distant family home, an external internship or cooperative site, study abroad, and so on. Obviously, the university’s greatest legal and ethical responsibility pertains to campus, but when a student (or faculty or staff member) is murdered in any one of the three loci, it affects that individual, his or her kith and kin, and diminishes the entire university community to some extent.

Table 1.2 Homicides on Campus, 2000–2004

In addition, it is important to obtain not only some basic numbers on the frequency of murder but also salient facts that relate to the cases (where they occurred, what was the cause, what sorts of weapon were used, etc.), so campus administrators can make minimal sense of what occurred and try to take preventive action.

To get a basic, broad picture of murders of university students, faculty, and staff, comprehensive Internet checking was completed by the authors; 262 cases were collected in which the subject was murder of people affiliated with a university (mostly students but also occasionally faculty and staff) between the years 2000 and 2008. (Information was collected on more than 100 additional cases from 1965 to 1999, but those cases likely represent a very small number of the applicable universe, especially with respect to the 1960s and 1970s.) It cannot be claimed that the 262 cases considered for the first 8 years of this decade represent a true scientific survey. It is likely that the Internet, reflecting a broad range of journalistic practices, would tend to pick up disproportionately the more interesting or dramatic of cases, nor can one pretend to have assembled even a majority of relevant cases for 2000–2008. Further, the likelihood that the Internet tends to employ popular rather than scholarly sources should be acknowledged, possibly entailing an increase in inaccuracy of detail. However, the assembled data for the present decade offer a broad-based view of the matter at hand.

Researchers made certain exclusions in collecting cases: (a) negligent homicides (e.g., driving under the influence [DUI] or unintentional alcohol poisoning), (b) deaths involving late-term or just-born babies (this seemed to belong to the topic of abortion), (c) speculative cases where it was not clear that murder took place (e.g., the so-called Smiley Face Murders where accidentally drowned students might have been mislabeled as murder victims), (d) and missing persons cases (those likely rooted in flight rather than foul play; Piehl, 2008).

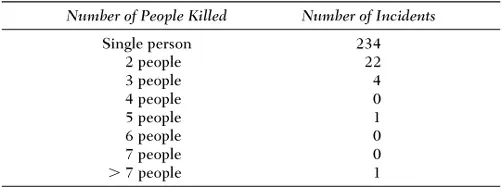

Table 1.3 tabulates the 262 cases by the number of people murdered per incident at the university. Out of respect for innocents here and throughout this chapter, people who kill themselves after murdering others are not counted as murder victims. They are instead considered “special-circumstance” suicides. Also excluded for present purposes are nonfatal casualties, meaning those who were wounded or injured.

It is clear that when homicide occurs in relation to university people—at least according to this sample—in the vast majority of instances, it involves a single victim.

The causes for single murders occasionally relate to mental health issues. For example, in May 2003, Biswanath Halder, a 62-year-old former student, who suffered from depression and delusions of persecution and who had trouble maintaining minimal self-care, conducted a 7-hour gun battle with police on the campus of Case Western Reserve University in which miraculously only one person was killed (Kropko, 2005). Sometimes a single murder is rooted in discrimination (such as with Jesse Valencia, of the University of Missouri, who was killed in 2004 by Steven Rios to cover up a gay relationship; Slavit, 2008). Sexual predators whose given names or nicknames have become infamous, like Ted Bundy, the Hillside Strangler, and the Rainy Day Murderer, alongside less-notorious sexual offenders, were frequently found (Larsen, 1980; Nelson, 1994; Rainy Day Murders, 1969; Schwarz, 2004). However, other common reasons are rooted in robbery, burglary, carjacking, professional or personal jealousy, escalating verbal and physical altercations, gang activity, drug dealing, and/or domestic violence.

Table 1.3 Murders of University People: 2000–2008

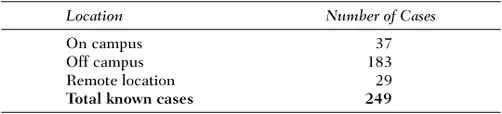

Table 1.4 Locations of Murders

The causes that pertain to single murders also tend to apply to double murders. One murder escalates to two generally because of situational factors. For example, two people rather than one walking home at night might create the occasion for a double rather than a single murder if a mugging takes place, or the obsessed individual who confronts an ex-partner might fatally harm another if the intended victim is in the company of a friend or associate when contact occurs.

Table 1.4 records where murderous events took place in which one or two people were killed (a sample of 249 cases).

The results indicate that campuses, given their community focus, self-containment (in many cases), and extended protection (oversight ranging from resident assistants to campus police) tend to be less dangerous than off-campus locations. In addition, while the line allotted to remote locations has the lowest single entry, considering the number of students and the amount of time spent on campus as opposed to the same measures for remote locations, the advantage in protection falls to the former category rather than the latter.

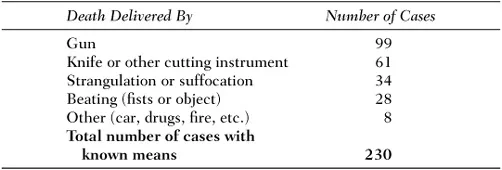

In single and double murders, Table 1.5 records the principal means of administering death.

Guns, especially handguns, are by far the most common single means death is administered in cases involving one or two fatalities on campus (in this sample); however, knives are not insignificant in the picture. Further, strangulation is relatively common, especially in cases associated with sexual assault.

Table 1.5 Principal Means of Administering Death

It also should be asked if the source of the violence is internal or external. For example, in September and October of 2000, two 19-year-old Gallaudet University students, were killed on campus in separate incidents by blunt force trauma in one case and stabbing in the other. The killer was Joseph Mesa, another Gallaudet student (Ramsland, 2004). However, in January 2007, a University of Tennessee alumnus and his student girlfriend were abducted from an off-campus restaurant and tortured, raped, and killed by a group of men (and one woman) not associated with any university (Sanchez, 2007). The University of Tennessee incident was graphically much more violent and disturbing, but the Gallaudet incident was haunting ...