![]()

1

REFLECTIVE CASE LEADERSHIP FRAMEWORK

Community colleges, like many other postsecondary institutions, are in an environment marked by increased pressures for institutional (e.g., academic, structural, governance, infrastructure, financial sustainability) change. A number of external forces driven by public scrutiny, increased accountability, fiscal downturns, and evolving political landscapes are responsible for these pressures. To alleviate these pressures, leaders must strive toward actualizing student success (e.g., persistence, achievement, attainment, transfer), promoting workforce training, fostering economic development, serving the needs of the local community, and increasing transfer and terminal degree rates. This requires future leaders and administrators at each level of the community college hierarchy to use theory as a tool to guide their practice and, ultimately, transform their institutions. In doing so, leaders will be better able to understand the myriad viewpoints, factors, and intricacies associated with issues confronting community college leaders; organize various constructs (e.g., players, power dynamics, organizational culture, setting, unaccounted-for circumstances) associated with a given issue, providing them with a more comprehensive view of the complex challenges that they encounter; predict the potential outcomes of an issue, as well as actions of stakeholders; and control and guide stakeholders, processes, and structures to achieve desired outcomes. Utilizing theory in conjunction with case study analysis affords community college leaders with the tools needed to comprehensively interrogate and inform decision-making processes.

Case Study Approach

Through the analysis of case studies that deal with actual situations confronting today’s community college (i.e., program development, demographics of the student body, staff recruitment and hiring, finance, political pressures, rural and urban community college students), the next generation of leaders will gain valuable insights that are typically learned only through experiential knowledge (i.e., on-the-job training). The cases presented in this book are based on real-life and fictionalized accounts of issues encountered by mid-and executive-level community college leaders throughout the nation. Great efforts were made to ensure that the cases presented are representative of the complexity of issues facing community college leaders (i.e., competing factors, ideologies, and demands). Thus, cases require readers to employ an advanced skill set (e.g., critical-analytical, human relations, political, emotional intelligence, problem resolution, conceptual, technical) while considering these competing interests to guide next steps in the decision-making process.

The benefits of using case study analysis in leadership development are numerous. They include exposing leaders to the predominant issues facing college leaders (e.g., accountability, fiscal constraints, diversity, governance), which may involve issues beyond their realm (e.g., region, position, institutional type); providing leaders with a platform to sharpen their problem-solving skills; allowing leaders to simulate the process of resolving a critical issue in a protected and supportive learning environment where errors can serve to further the learning experience without having detrimental effects on a career or an organization; and enabling leaders to engage in democratic (collaborative work) processes in which individuals are encouraged to present various perspectives with the ultimate purpose of arriving at sound resolutions.

Overall, using a case study approach challenges leaders to move beyond their understanding, preference, or level of comfort to consider alternative approaches to addressing problems that they face in their practice. Moreover, most leaders generally have not considered what type of leadership style they employ, let alone move beyond that style to use new paradigms. For instance, a leader may employ a bureaucratic framework, without understanding the implications, strengths, or weaknesses of that frame. A single frame carries with it a myopic approach to problem solving; however, the challenges that leaders face in their practice are complex and dynamic. Thus, to offset the limitations of using a single leadership approach, we call for a unified approach in which leaders employ multiple leadership lenses. These lenses, when used with intentionality, can result in more sound decisions. However, successfully deploying multiple frames is easier said than done. This unified approach requires leaders to think beyond what they know; learn new ways of being; be open to new thoughts, dispositions, and models; and, most important, be flexible and adaptable to unforeseen and “never seen” challenges in the community college.

Nevarez-Wood Leadership Case Study Framework

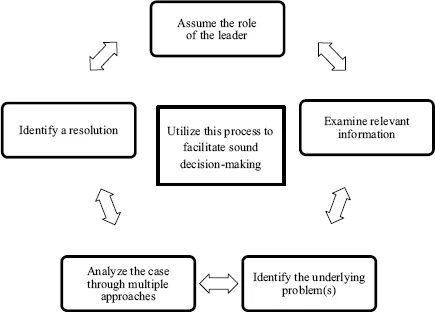

Leaders should use the steps discussed in the following subsections in approaching a resolution to case study analysis, keeping in mind that the framework presented is multidimensional, fluid, cyclical, and nonstatic (see Figure 1.1). Moreover, it serves as a guide to facilitate effective and efficient case resolution. It is particularly important for community college leaders to use the framework because it connotes the importance of reflective theory–practice whereby information considered, decisions made, and actions taken are continually and critically reflected on by leaders; it accounts for and provides guidance (a road map) in addressing the multiple missions of the community college, which include open access, comprehensive educational programming, serving the local community, lifelong learning, teaching and learning, and student success (see Nevarez & Wood, 2010); and the convergence of theory and practice integrated within this framework empowers leaders to make sound decisions.

FIGURE 1.1

Nevarez–Wood Leadership Case Study Framework

What follows is a step-by-step process that enhances leaders’ abilities to resolve complex and dynamic problems. Leaders may also reference Nevarez and Wood’s (2012) “A Case Study Framework for Community College Leaders,” which provides additional information about and contextualization of each step.

Step 1: Assume the Role of the Leader

There are two primary types of leadership approaches: informal and formal. Informal leaders gain their influence outside the formal authority, titles, or structure of an organization. Their power is vested by their peers who bestow upon them a sense of credibility, respect, influence, and backing. This, in turn, provides these leaders with considerable influence, including their commitment to the best interests of organization affiliates, people skills, knowledge, proven accomplishments, tenure, and insight to “getting the job done.” By contrast, formal leaders are given organizational authority based on the power (e.g., rights, privileges, responsibilities) bestowed upon their position. The power and authority of holding a formal position is reinforced by the ability to serve rewards and punishments to subordinates. While leaders, through human relations, political maneuvering, and/or performance, may enhance their organizational power, the mere authority of their position demands a baseline of influence. When reading the case, we ask that leaders assume the formal role (e.g., president, vice president, dean, program director, department chair, faculty) of a leader who is able to influence the decision-making process. However, we ask that formal leaders consider how informal leaders can be allied with to support problem resolution and organizational success.

Although often used interchangeably, leadership and administration are two distinct concepts. Leadership is the act of “influencing and inspiring others beyond desired outcomes” (Nevarez & Wood, 2010, p. 57). Leaders are able to motivate their followers (through communication, interpersonal relations, vision, and investment in others) to meet the best interests of the organizations that they serve. In this approach, the relationship between the leader and the follower is one marked by collaboration; followers are often viewed as affiliates or teammates in the decision-making process. Administration refers to an autocratic approach for managing others. This approach relies on a hierarchical (top-down) style bolstered by the administrators’ reliance on policy, rules, and procedures. In general, administrators manage their employees through a style that is controlling, directive, and restrictive in nature; thus, employees are viewed as subordinates. Some case studies will require leaders to assume the role of leader or administrator in decision making; whereas, others will require both approaches.

Step 2: Examine Relevant Information

Each respective case is informed by contextual factors. These factors are integral considerations in the decision-making process. Leaders should begin by identifying information presented in the case (e.g., setting, stakeholders, special circumstances). They should then delineate what information is key to case resolution. Leaders can use the following guidelines in examining relevant information:

1.List information contained in the case focusing on the setting, the stakeholders or groups involved, and special circumstances (e.g., unknown information, factors that cannot be planned for) surrounding the case.

2.Contextualize this information by providing substance to each point listed. Consider how the information identified is interconnected and influences the dynamics of the case. For example, when contextualizing information relevant to the setting, ask yourself: What is the climate of the institution? What is the demographic makeup of the individuals involved in the case? What are the normative behaviors, traditions, values, and institutionalized practices involved?

3.Reflect on what information is key to understanding and driving the resolution of the case. We suggest either circling or listing this information on a continuum ranging from least relevant to most relevant.

Step 3: Identify the Underlying Problem(s)

Community colleges are complex sociopolitical organizations. Therefore, the problems encountered by leaders in these organizations are often multifaceted and dynamic. In many circumstances, multiple problems are at play in a single case. Largely, there are two types of problems: primary problems (core issues) and ancillary problems (problems that are the by-products of primary problems). Often, leaders can get bogged down trying to treat ancillary problems without addressing the “root” issue at hand. For example, a community college may become concerned when its workforce development students are experiencing poorer than expected market outcomes (ancillary problems), such as low hiring rates of graduates, low job retention rates, low salaries, and low promotions; however, the root problem may be a disconnect between what is being taught in the classroom and what is expected in the market (e.g., too philosophical, outdated information, lack of relevancy, low applicability). When engaged in case resolution, leaders should consider the following steps:

1.Identify all the problems associated with a given case.

2.Identify the relationship (if any) between these problems.

3.Denote which problems are root problems and which are ancillary.

4.Use this information to drive the decision-making process, focusing on primary problems first and to a lesser degree on ancillary problems.

Step 4: Analyze the Case Through Multiple Approaches

This book presents multiple leadership approaches and theories. Readers are to use the leadership approaches provided in each respective chapter to address the cases presented. Each theory is undergirded by a philosophy of leadership values, which has direct implications for the “practice” of leadership. Further, each approach has associated strengths and weaknesses, depending on contextual factors relevant to each case. Astute leaders understand these strengths and weaknesses of each respective theory and are critical in the selection of the theory (or theories) that provides for optimal case resolution(s).

Having a cursory or surface-level understanding of each theory presented will provide only limited support in case resolution. Therefore, when reading each chapter, we suggest “getting into the theory”; by this we mean that readers must understand the intricacies, complexities, and nuances of the theory. This will require reading and rereading each chapter, ruminating on the elements of each approach. In doing so, readers must simulate the theory in its purest form, irrespective of their personal bias, disposition, perceptions, or initial inclination for case resolution. As leaders become more perceptive at case study analysis, they can also consider how multiple approaches may be fused or used simultaneously in the resolution of a case. The end goal is to ensure that leaders acquir...