![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

EXISTING THEORIES, EXAMINING CLAIMS, AND PROPOSING NEW UNDERSTANDINGS![]()

1

SEIZING RESPONSIBILITY

Using Actionable Knowledge to Promote Fairness

Edward P. St. John

Aspiring student affairs professionals enter their master’s and doctoral programs with prior experiences that inspired their choice of a specialized field in which to support students’ navigation of education systems. Twenty-first century universities differ from those of the midtwentieth century, the period during which most theories of college student development originated. Society is more diverse, a consequence of both changing demographics and the internationalization of educational opportunities. The idea of globalization is central to higher education in the twenty-first century, and it is crucial that student affairs administrators and aspiring professionals develop skills that encourage openness to learning about the perspectives of others as they navigate their educational and career pathways and encourage others to make informed choices in an increasingly diverse society. This chapter makes two interrelated arguments: (a) Both current and aspiring professionals in student affairs share responsibility for promoting fairness and equity in educational systems; and (b) assuming this responsibility provides opportunities for developing and using actionable knowledge in the process of change and adaptation within colleges and universities in globalizing societies.

Social Responsibility in Context

We live and work in colleges and universities transitioning to universal opportunity for access, but there are growing inequalities owing to failures of school reform in many locales, resistance to affirmative action in states with elite institutions of public higher education, and inadequacies in public funding for need-based student aid. The result is a paradox: In spite of growing access, social stratification is increasing. Although college may now be a necessity for gaining or maintaining access to middle-class professions across generations (e.g., business administration, education, engineering, health care), gaining access to and staying in college is a complicated matter. Although student affairs professionals are not responsible for these conditions in their colleges and universities, recognition of the contemporary context for student life in universities is a starting point for encouraging students in their efforts to navigate educational systems and for professionals to collaborate on the design and testing of remedies to problems in the educational system.

Globalization and Academic Life

The emphasis on expanding the number of people with advanced education in science and engineering is a commonality among nations engaged in the global economy. Although workforce policies in the United States emphasize employment in high-paying technical jobs (Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce, 2007), the same arguments prevail in the international literature on access (Yang, 2011; Yang & St. John, in press). Indeed the culture of global competitiveness is now not only evident in public policy, but is also deeply embedded in the experiences of students as they develop college aspirations, choose a college, and navigate academic pathways.

Institutions also face new pressures that differ from the ones faced in the liberal arts culture that prevailed in undergraduate education in the mid-twentieth century when student development theory was originally developed. Indeed, the idea that students should use their first two years to choose a major is being replaced by new pressures to promote persistence in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math), which essentially limits student choices because of the constrained curriculum required to prepare for advanced course work in these fields (St. John & Musoba, 2010). Parents and older siblings also often pressure students to choose majors that emphasize science and technology (St. John, Hu, & Fisher, 2011). There is a stress on improving diversity and promoting learning environments that support diversity (e.g., Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, & Gurin, 2002; Hurtado, Milem, Clayton-Pederson, & Allen, 1998). Thus, professionals in higher education and student affairs confront many circumstances that undermine the espoused goals related to the development of global and social consciousness as they engage in overcoming recurrent, historic patterns of conflict within educational organizations.

Social Justice as a Goal in Student Affairs In a global context that supports diversity, the student affairs profession is at the intersection of the new goals of diversity and social justice and the older traditions of liberal education with its history of elitism. The American College Personnel Association (ACPA) supports an ethical code for the profession:

These standards are: 1) Professional Responsibility and Competence; 2) Student Learning and Development; 3) Responsibility to the Institution; and 4) Responsibility to Society… . Student affairs professionals should strive to develop the virtues, or habits of behavior, that are characteristic of people in helping professions. Contextual issues must also be taken into account. Such issues include, but are not limited to, culture, temporality (issues bound by time), and phenomenology (individual perspective) and community norms. Because of the complexity of ethical conversation and dialogue, the skill of simultaneously confronting differences in perspective and respecting the rights of persons to hold different perspectives becomes essential. (ACPA, 2006, pp. 1–2)

This statement conveys the duality of the profession. On the one hand, the profession itself is situated within the concepts of professional responsibility, including responsibility to the institution and society. Yet the statement concludes that “simultaneously confronting differences in perspectives and respecting the rights of persons to hold different perspectives becomes essential.” This places the concepts of justice and fairness as central to the profession.

Universities as Global and Local Contexts Institutions of higher education are typically far from being socially just environments, and student affairs professionals frequently find themselves in a position of having to represent the voices of students marginalized by the system. Some of the forces that marginalize students who are historically underrepresented include:

• Institutionalism: Historically established patterns of behavior reinforced by bureaucratic behavior and therefore resistant to change

• Managerialism: The use of decentralized authority structures, supported by modern management methods (i.e., data systems and formal and informal rules of the system)

• Corporatization: Systems of reporting and accountability that reinforce rigidities in systems and recurrent patterns of inequality

• Marketization: Shifts in the funding of higher education, including student aid (e.g., use of loans rather than need-based grants), that increase the challenges of those least able to pay the costs of continued enrollment in the educational system

These systemic forces frequently come into direct conflict with the aims of the profession, especially the idea of simultaneously confronting diverse perspectives and representing the rights of people. The practice of this ideal can be especially difficult for new professionals in the field, particularly when their organizational superiors have tacitly accepted the institutional norms and practices that have created inequalities and marginalized those who are most underrepresented because of their life circumstances.

Pillars of Moral Responsibility As new professionals engaged in their graduate education in higher education and student affairs gain experience of professionals, they are frequently confronted by challenges that test their character. In my first decades as a professor in the field, I conducted several action studies related to teaching leadership and on interventions in schools and colleges that promoted justice and fairness. I engaged in “action experiments” that involved working with students to test theories of action in practice (St. John, 2009a). Through this process, I reached five critical understandings about professional development:

1. The individual professional is responsible for moral centering and action. Faculty and interventionists should not advocate values, but rather facilitate discourse on difficult and problematic issues in practice.

2. Moral development in adulthood involves centering one’s self in the ethics of both justice and care. Professionals of all types bear responsibility for their own moral development as professionals—a lifelong task.

3. There are gaps between the espoused theories of practice held by most professionals and their actions as practitioners. Learning how to engage in practices that reduce these gaps is crucial to professional development and moral consciousness.

4. Human development through adulthood creates opportunities for professional growth and potential for conscious action, especially if the inherent sequence of learning about self and practice is realized and acted upon.

5. Post-conventional moral reasoning involves critical and spiritual reflection on morally problematic situations along with testing strategies that might transform them. (From St. John, 2009a, pp. 17–22)

We can view these understandings within the developmental process in student affairs:

1. As undergraduates, students learn about the student affairs profession and develop inner commitments that lead them to the field of study (restated understanding 1).

2. Study of the field of higher education and student affairs provides means of centering oneself in the codified content along with moral and ethical codes of the field (restated understanding 2).

3. When new professionals enter practice they are confronted by the gaps between espoused intent, as defined by the values of the field, and actual behaviors in colleges and universities, reinforced by the formal system (restated understanding 3).

4. As students grow and develop as professionals in the field, they have many opportunities to learn about themselves, their institutions, and the role of student affairs in promoting care and justice (restated understanding 4).

5. If these practices are centered within one’s own core values, there are opportunities for self-actualization and integration (restated understanding 5).

Making our way through this journey of professional life requires building a personal process of professional learning, uncovering gaps between values and action, coupled with the process of experimenting with alternative approaches to remedying challenges that emerge.

Social Agency in Action

My argument is that professional learning provides us means of dealing with issues of social injustice and inequality within professional practice, a process of seizing responsibility as a professional, an ideal that is entirely consistent with the ethical code of professional development in higher education and student affairs, as stated in the ACPA ethical code. This argument was fundamentally influenced by listening to concerns raised by students in courses I taught, including Kim Kline when she was enrolled in my graduate course on professional development at Indiana University. I review the ways Kim’s interventions and questioning challenged me to rethink the role of social agency in professional practice before noting the importance of theory reconstruction as an inner guiding force in professional development.

Kline Contests Functionalist Reasoning I had used a case method of teaching (Arygris, Putnam, & Smith, 1985; Argyris & Schön, 1974) for more than a decade before Kim showed up in my class. Kim not only had her master’s in student affairs when she started the doctoral program at IU, but she had prior professional experience; she was an experienced professional returning for a doctoral degree.

Kim’s case for the class, which is included with her permission in College Organization and Professional Development (St. John, 2009b), provides an example of an adaptive, strategic intervention that did not test assumptions, but did promote fairness. Specifically when working as an advisory to a student leadership group, she listened as the president of the student organization dismissed a request by a minority group to have a booth at a student event. When the case arose, the student president dismissed it with comments that seemed racist at the time. Kim did not ask questions in the public situation about the reasoning for dismissing the request, because she feared increasing the racial unrest. Instead, asserting her authority, she intervened in a way that enabled the minority student group to participate in the event as they had intended. This intervention promoted the social agency of a group that had been subject to discrimination, but did not surface and address the underlying problem in the public situation.

This case raised an issue that had concerned me for decades, since I was a graduate student. Her case used a strategic intervention to turn the course of a conversation with student leaders from a racist solution to one that was more inclusive. Yet when we used the theory of Argyris and Schön (1974) to analyze the case, it was classified as Model I, because it was closed to public testing of the core idea in the intervention, even though it changed the course of action. I had always been troubled that the original theory was situated in the functionalist theory of organizations and could only be implemented in top-down organization, that is, when leaders in the organization realized the need for—and actualized the practice of—open discourses about commitment to theories of action and intervention methods.

My insight from our class discussion of Kim’s case was what was needed to distinguish the social agency of student affairs professionals from the institutional roles they played, to better understand the conflict between those two roles. I subsequently worked with Kim on an action experiment that further tested the idea of social justice as a central factor in professional development (Kline, 2007). Not only did I encourage Kline along her path, I began to more seriously ponder the problem of professional development and lack of sound theories of action to inform adult development pathways traveled by people who developed and used actionable knowledge to make changes in pursuit of social justice, a central goal of student affairs professionals in higher education.

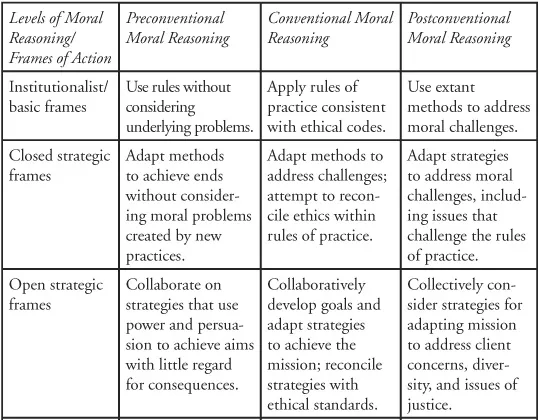

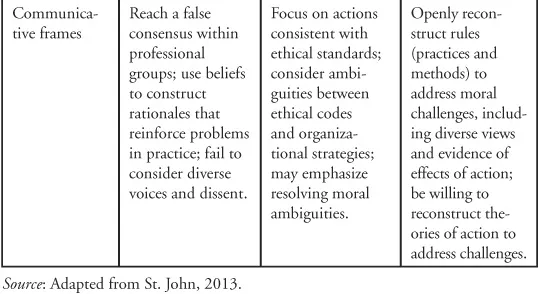

Reconstructing Theories of Action This brings us to another, closely related core issue: the need for a theory of the development of moral reasoning compatible with the professional pathways people can potentially travel as they attempt to reconcile and reduce gaps between their espoused values and their actual practices within their profession. This led toward the reconstruction of the concepts used by Kohlberg (1981, 1984), Habermas (1990, 2003), and Argyris (1993). The resulting framework for thinking through professional and personal trajectories toward maturity and moral judgment, reflecting understanding—and the social agency—of others, is presented in Table 1.1.

The frames of action illuminate an underlying developmental sequence of frames of professional reasoning, and the moral dimension distinguishes among three types of reasoning: conventional, which involves working within the rules of the system; preconventional, engaging in breaking or “working around” the rules to achieve goals or solve problems; and postconventional, which involves addressing critical issues while also considering the limitations of the rules. The four types of framing are:

TABLE 1.1

FRAMEWORK FOR REFRAMING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MORALREASONING AND PROFESSIONAL ACTION

• The institutionalist frame, which situates professional action and problem solving within the institutional rules system using expertise;

• The closed strategic frame, which involves aiding schools in adaptations through the use of professional discretion to solve problems;

• The open strategic frame, which involves enabling conversation within organizations to address problems confronted as groups work on the initiatives of the organization; and

• The communicative frame, which focuses on solving social critical problems that emerge within systems as a central form of action.

There is an underlying sequence of skill development within these frameworks. For example, a person needs to understand the institutional rules in relation to professional knowledge (institutionalist frame) before adapting professional practices in problem solving (closed strategic). At the same time, the actual behavior that goes on in a specific probl...