![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

THE STRENGTHS OF OUR STUDENT VETERANS AND THE CHALLENGES THEY FACE![]()

1

SETTING THE STAGE

Student Veterans in Higher Education

I came home May 17th. I started classes May 27th.

—Wayne, former Marine (Wheeler, 2011, p. 108)1

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 was passed on June 22, just sixteen days after the D-day invasion of the Normandy beaches. This act stipulated that “any person who served in the active military or naval forces … shall be entitled to vocational rehabilitation … or to education or training.” Service members were paid “the customary cost of tuition, and such laboratory, library, health, infirmary and other similar fees as are customarily charged, and may pay for books, supplies, equipment, and other necessary expenses” (Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944). This act became known as the GI Bill, and by 1950 more than 6 million veterans had enrolled in college using these benefits, changing the face of higher education. Educational benefits have been provided to military veterans ever since through a succession of legislative acts. The Post-9/11 Veterans Educational Assistance Act (often called the Post-9/11 GI Bill) was passed in 2009 and is the newest legislative version of this benefit. A unique feature of the Post-9/11 GI Bill is that benefits can be transferred to a spouse or child under certain circumstances, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) estimates that 594,000 student veterans or their dependents received federal aid from this program in 2012 (College Board Advocacy & Policy Center, 2012, p. 18). The Post-9/11 GI Bill generally increases the benefits for military veterans and their dependents compared to the previous (1984) Montgomery GI Bill (Radford, 2009, pp. 1–2), and as a result a new wave of student veterans is entering postsecondary education. Although not as numerically dominant as their 1944 predecessors, it seems likely that they too will leave their mark on higher education.

Students who are active-duty service members, reservists, members of the National Guard, and veterans (referred to throughout the rest of this book as “student veterans” or “military students”)2 constituted 4.2% of the total undergraduate population in the United States during the 2007–2008 academic year—a total of 875,000 students enrolled nationwide (Radford & Wun, 2009). Recent drawdowns in the U.S. military, coupled with the Post-9/11 GI Bill, have more than doubled this number, and 88.2% of the institutions that participated in the most recent American Council on Education (ACE) survey indicated that they had experienced moderate or substantial gains in student veteran enrollment (McBain, Kim, Cook, & Snead, 2012, pp. 7–8, 49). ACE predicts that almost 2 million veterans returning from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars have enrolled or will soon enroll in postsecondary education (American Council on Education, 2008, p. 1). Institutions that can leverage the strengths of student veterans and that can ease the challenges of their transition to higher education will find that they add immeasurably to the educational experiences of the entire academic community.

Student veterans enter higher education with many advantages, for the experience of serving in the armed forces provides “greater self-efficacy, enhanced identity and a sense of purposefulness, pride, camaraderie, etc.” (Litz & Orsillo, 2004, p. 21). As one student veteran stated,

I am much more driven than I would have been had I attended school right after high school. I see the value, not only monetarily, but [in terms of] time and effort, in putting forth the necessary effort to excel at my studies. (Doenges, 2011, p. 55)

Student veterans have financial independence from their parents and have had professional training and development opportunities that will benefit their experience in college (Dalton, 2010, p. 1). Enlistment in the armed forces results in higher levels of college enrollment and increases the likelihood of attaining a two-year degree—albeit after a time lapse of 16 years (Loughran, Martorell, Miller, & Klerman, 2011, pp. 40, 49).

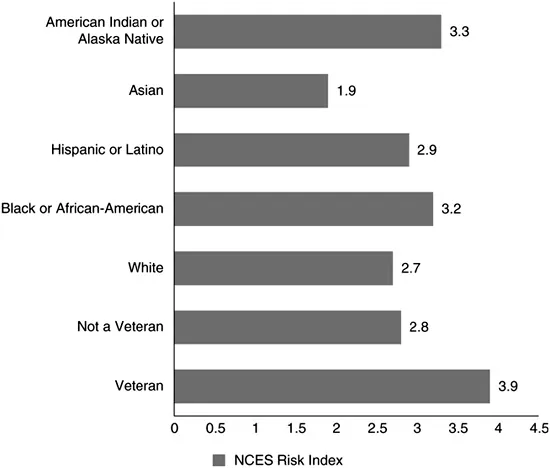

Student veterans also face significant challenges. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), veterans are 21.2 percentage points less likely than nonveterans to attain a bachelor’s degree and are 4.1 percentage points more likely to drop out of postsecondary institutions without attaining a degree of any sort. The number of veterans who have an average collegiate GPA below 1.75 is 59.5%, and only 26.5% expect to achieve a bachelor’s degree or higher. Student veterans have typically been out of school for some time when they transition back to higher education and are more likely to have earned average grades while in high school (Kings-bury, 2007, p. 71). Six-year graduation rates tend to be lower for student veterans, but this measure may not be the most effective way of judging student veteran success. Any student who is deployed, for example, will miss at least one year of college, and enlistment clearly delays graduation (Loughran et al., 2011, p. 49). As a result of these and other factors, veterans have a higher risk index for success in postsecondary education than any racial or ethnic minority (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Risk Index for Student Success in Higher Education (U.S. Department of Education, 2011).

This index of risk is based on the sum of seven possible characteristics that may adversely affect persistence and attainment: delayed enrollment, type of high school degree, attendance pattern, dependency status, single parent status, has dependents, and work intensity while enrolled.

In addition to these risk factors, student veterans may experience transitional challenges as they leave the military and enter higher education. The challenges associated with this transition are heightened when a student has a disability, for these students may need additional resources to succeed.

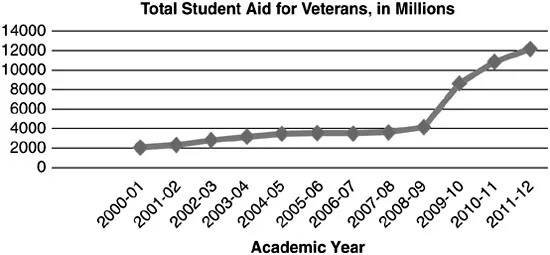

Veterans value education and believe that it is a priority despite the challenges they face. The military’s educational benefits play a substantial role in a person’s decision to enlist and provide potential students with high educational aspirations the means to attain their goals (Kleykamp, 2006, p. 286). As one currently enlisted student said, “I am taking classes. I don’t see myself ever stopping. There is so much to learn out there. I want to go as far as I can” (Cook & Kim, 2009, p. 20). Student veterans have resources that many at-risk student populations do not have. As illustrated in Figure 1.2, federal student aid for veterans increased 424% from 2001 to 2012, even after adjusting for inflation. During the 2008–2009 academic year the federal government provided $4.1 billion in financial aid to veterans, but this amount jumped to more than $12.2 billion by 2011–2012 owing to the effects of the Post-9/11 GI Bill (College Board Advocacy & Policy Center, 2012, p. 10).

Figure 1.2 Total Student Aid for Veterans Used to Finance Postsecondary Educa-tion Expenses in Constant 2011 Dollars (in Millions), 2000–2001 to 2011–2012 (College Board Advocacy & Policy Center, 2012, p. 10).

Note: Data from the VA indicates that 40% of student financial aid from the GI Bill goes to public institutions (both two-year and four-year), 24% goes to private nonprofit institutions, and 36% goes to for-profit institutions (College Board Advocacy & Policy Center, 2011, p. 16).

Given these resources, institutions that can successfully recruit and retain student veterans will find themselves at a competitive advantage, especially in an era of tight fiscal resources and increasing pressure to make ends meet.

Returning service members bring great strengths to higher education. They are mature, have had significant life experiences, and bring a cross-cultural awareness to the college campus. One of their greatest strengths is that they are highly motivated to serve others. The same NCES report that indicated that veterans are at high risk for academic failure also documents that they volunteer more hours per month (22.9) than any other demographic and 7.6 hours more on average than nonveteran students. Colleges and universities can build on these strengths to develop academic programs that enrich both the institution and its community. Institutions that wish to enhance student veteran success in significant ways also need to develop holistic initiatives to mediate student veterans’ transition into higher education. Colleges and universities can fulfill the educational promise of each student veteran only by recognizing both their strengths and their challenges. As one Army veteran noted, “A resilient service member and a truly military-supportive school is a powerful partnership!” (Zackal, 2012).

Who Are Our Student Veterans?

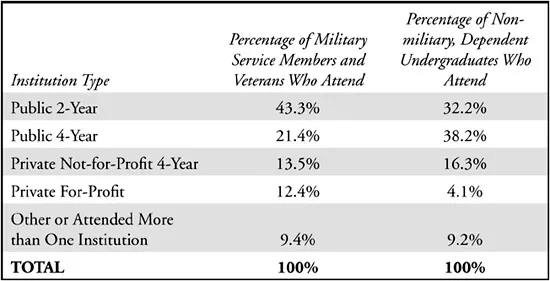

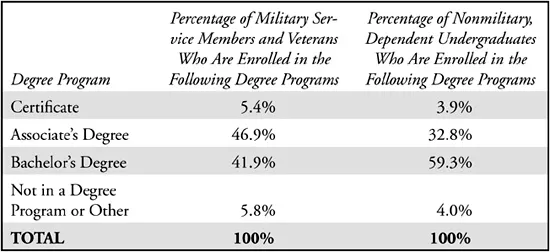

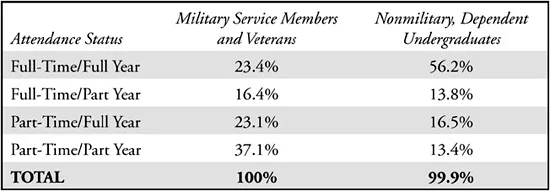

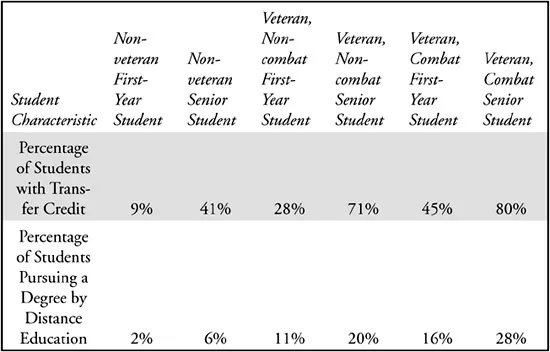

Veterans returning to school under the Post-9/11 GI Bill are demographically different from the typical incoming first-year student. A total of 84.5% of all military undergraduates in the classroom are older than the traditional college student, 47.3% are married, and 47.0% have children, including 14.5% who are single parents (Radford & Wun, 2009). Military members and veterans as a group seek associate’s degree programs at two-year colleges at a higher rate than the traditional college population (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2). Combat and noncombat veterans are more racially diverse than nonveterans, more likely to be first-generation college students, and more likely to have attended public schools than the nonveteran population (National Survey of Student Engagement, 2010, p. 17). Almost 77% of student veterans attended school part-time during the 2007–2008 academic year, and only 37.7% of military undergraduates used veterans’ education benefits (see Table 1.3). Combat veterans who are first-year students are five times more likely to be transfer students and eight times more likely to enroll in distance-learning courses than nonveteran first-year students (see Table 1.4).

Finally, student veterans are overwhelmingly male compared to the general student population: 73.1% of undergraduate student veterans are male, compared to 35.2% of nontraditional nonmilitary students and 47.1% of traditional nonmilitary students (Radford, 2009, p. 7). Student veterans, as these data show, differ in important ways from the “traditional” student body. Programs and services that are designed to assist first-time full-time students may not be ideal for reaching student veterans.

TABLE 1.1

Distribution of Undergraduates by Military Status and Institution of Enrollment (Radford & Wun, 2009, p. 6)

Source of Data: 2007–2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

TABLE 1.2

Distribution of Undergraduates by Military Status and Degree Program (Radford & Wun, 2009, p. 6)

Source of Data: 2007–2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

TABLE 1.3

Distribution of Undergraduates by Military Status and Attendance Status (Radford & Wun, 2009, p. 6)

Source of Data: 2007–2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

Student Veterans and Disabilities

Veterans returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) are unique from past generations of veterans. Advances in body armor, vehicle protection, medical procedures, and treatment mean that a greater number of these veterans will be enrolling in college with both visible and invisible disabilities. The percentage of OIF, OEF, and OND veterans who have disabilities is uncertain, but estimates range as high as 40% (American Council on Education, 2010, p. 1; Grossman, 2009, p. 4). These disabilities can complicate a student’s transition to college, and higher education must devise ways to proactively and respectfully address these challenges if we are to offer all our student veterans the greatest prospect for success.

TABLE 1.4

Student Characteristics by Veteran Status and Class Level, by Percentage (NSSE, 2010, p. 17)

Source of Data: 2007–2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

Blasts are the most common cause of combat injuries (Gawande, 2004; Gondusky & Reiter, 2005; and Murray et al., 2005), but also prevalent are projectile injuries from “bullets and fragments, transportation accidents, and other environmental and combat hazards” (Kennedy et al., 2007, pp. 895–896). Many veterans have survived amputations; severe burns; hearing and vision loss; and head, spinal, and other serious injuries (Bilmes, 2008, p. 84; Lew, Jerger, Guillory, & Henry, 2007; Thatch et al., 2008). More than 250,000 troops discharged from the military by 2008 required treatment at medical facilities, including at least 100,000 with mental health conditions and 52,000 with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bilmes, 2008). Hoge, Auchterlonie, and Milliken (2006) found that

the prevalence of reporting a mental health problem was 19.1% among service members returning from Iraq compared with 11.3% after returning from Afghanistan and 8.5% after returning from other locations. … Thirty-five percent of Iraq war veterans accessed mental health services in the year after returning home; 12% per year were diagnosed with a mental health problem. (p. 1023)

In a later study, Hoge et al. (2008) discovered that

of 2525 soldiers, 124 (4.9%) reported injuries with loss of consciousness, 260 (10.3%) reported injuries with altered mental status, and 435 (17.2%) reported other injuries during deployment. Of those reporting loss of consciousness, 43.9% met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as compared with 27.3% of those reporting altered mental status, 16.2% with other injuries, and 9.1% with no injury. (p. 453)

Many of the soldiers who need mental health treatment do not report these problems or seek help owing to the stigma of seeking psychiatric assistance, especially in a volunteer army in which a disability designation may be seen as a hindrance to advancement and promotion (Hoge et al., 2004; Litz & Orsillo, 2004).

The studies mentioned here should not be used to stereotype student veterans, and it is important to remember that the majority of student veterans do not have any disability at all. It is clear, however, that a significant percentage of veterans are returning from OIF, OEF, and OND with varying types and degrees of disabilities. It is to the benefit of both these vet...