![]()

PART ONE

Understanding the Learning-through-Serving Proposition

The goal of part one is to prepare you for the experience of learning through serving. Some students begin their service-learning courses already understanding the foundations for this type of classroom-community experience through their own personal histories of volunteering and engaged citizenship. For others of you, the experience may be unfamiliar, untested territory. Chapters 1 through 3 will provide you with the steps for connecting yourself to the community and offer suggestions for how you might begin to experience yourself as a collaborator in learning through serving.

KEY SYMBOLS

Exercises of utmost importance to complete (working either on your own or in a group)

Optional exercises (strategies for gaining deeper insights into the issues)

Exercises that provide further resources and information in your quest for understanding community problem solving and change

![]()

CHAPTER 1

What are Service-Learning and Civic Engagement?

CHRISTINE M. CRESS

What are Service-Learning and Civic Engagement?

ACROSS THE UNITED STATES and around the world, students and their instructors are leaving the classroom and engaging with their communities in order to make learning come alive and to experience real-life connections between their education and everyday issues in their cities, towns, or states. If you are reading this book, you are probably one of these students. In some cases, you might even travel to a different part of the country or to another country to “serve and learn.” Depending on the curriculum or program, the length of your experience can vary from a couple of hours to a few weeks or months, and occasionally to an entire year. (If you are traveling across the country or internationally to your service-learning site, make sure to read chapter 12, “Global and Immersive Service-Learning: What You Need to Know as You Go.”)

In fact, this may not be your first volunteer, service, or service-learning experience. Today, many high schools require community service hours for graduation and many colleges require proof of previous civic engagement or community service as a part of the admission application.

These experiences are often referred to by multiple names: service-learning, community service, or community-based learning. Throughout this text we use these terms relatively interchangeably, but we also explore some important distinctions. The activities differ from volunteering or internships because you will intentionally use your intellectual capacities and skills to address community problems. While you will have an opportunity to put your knowledge and skills into direct practice, you will also learn how to reflect on those experiences in making your community a better place in which to live and work.

• Volunteerism: Students engage in activities where the emphasis is on service for the sake of the beneficiary or recipient (client, partner).

• Internship: Students engage in activities to enhance their own vocational or career development.

• Practicum: Students work in a discipline-based venue in place of an in-class course experience.

• Community Service: Students engage in activities to meet actual community needs as an integrated aspect of the curriculum.

• Community-Based Learning: Students engage in actively addressing mutually defined community needs (as a collaboration between community partners, faculty, and students) as a vehicle for achieving academic goals and course objectives.

• Service-Learning: Students engage in community service activities with intentional academic and learning goals and opportunities for reflection that connect to their academic disciplines.

For example, volunteering to tutor at-risk middle-school students is certainly valuable to the community. Similarly, working as an intern writing news copy for a locally owned and operated radio station is great job experience. Service-learning, however, is different. In service-learning you will work with your classmates and instructor to use your academic discipline and course content in understanding the underlying social, political, and economic issues that contribute to community difficulties. In essence, you will learn how to become an educated community member and problem solver through serving the community and reflecting on the meaning of that service.

How Is Service-Learning Different from Other Courses?

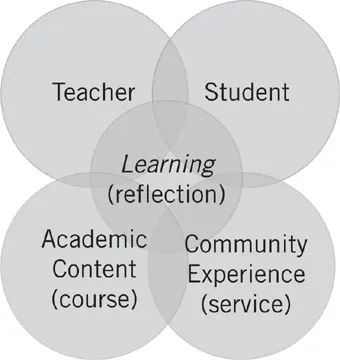

For clarity, we will most often use the term service-learning to characterize your community-based learning experience. Each faculty member may structure the experience slightly differently depending on the goals and objectives of the course and the needs of the community partner. What is most important for you to know is that service-learning is truly a different way of learning—thus the hyphen between “service” and “learning.” These two facets are interdependent and dynamic and vary from other forms of traditional learning in that the focus is placed upon connecting course content with actual experience (see figure 1.1).

Instead of passively hearing a lecture, students involved in service-learning are active participants in creating knowledge. The role of teacher and learner are more fluid and less rigid. While the instructor guides the course, students share control for determining class outcomes. At first, this new kind of pedagogy (that is, teaching methods) can seem quite strange to students. As you and your classmates get more practice working with each other in groups and connecting with your community, though, you may find it far more interesting than “regular” classes.

In many traditional learning environments, the instructor delivers the content of the course through lectures, assignments, and tests. In some cases, students may also complete a practicum or other hands-on experience to further their learning. In contrast, learning through reflecting on experience is at the center of service-learning courses, and faculty guide students as they integrate intellectual knowledge with community interactions through the process of reflection.

Figure 1.1. The Learning-through-Serving Model

One of the aspects of service-learning that may also make the experience enjoyable for you is that the experiential component connects to a wide range of learning styles. You may find that when you enter your service site, the needs of the community are quite different from what you expected. Say, for instance, that your service-learning involves teaching résumé writing to women staying at a “safe house” for survivors of domestic violence. In working with the women, you may discover that they also need professional clothing for job interviews. While they may still need your help in preparing résumés, their confidence in an interview may be undermined unless they feel appropriately dressed. As a service-learner, you might find yourself asking, “Now what do I do?”

You have probably succeeded thus far in your education because you have a certain level of ability to listen to lectures, take tests, do research, and write papers. However, for some students (including, perhaps, yourself) this does not come naturally. Instead, your skills may best emerge when interviewing community members or providing counseling assistance. Alternatively, you may excel at organizing tasks and developing project timelines, or you may be visually creative. In the previous example, you may be the best person to provide résumé assistance for the women, or it might make more sense for a classmate to assist with résumé writing while you call local agencies to inquire about clothing donations. Ideally, all students will find the opportunity to build from and contribute their strengths to the service-learning projects using different skill sets.

Along the way, your instructor and the course readings will further develop your range and repertoire of skills, knowledge, and insights, because service-learning courses invariably challenge students to consider where “truth” and wisdom reside. Moving more deeply into the previous scenario, for example, you might begin to wonder why domestic violence exists in your community. What role might the media play in portraying healthy and unhealthy domestic relationships? Do economic factors such as unemployment make any difference? What about substance abuse issues?

Stop for a moment and think about how you would answer the following questions as you ponder your own education and the relationship you see between in-classroom learning and the outside world:

• What is the relative value of solutions drawn from scholarly literature compared to ideas presented by students, faculty, and community partners?

• How can we move beyond stereotypes, preconceived ideas, misinformation, and biases to understand real people and real issues?

• How can we be solution centered?

• How can we examine external norms and societal structures?

• Which community values should we reinforce, which are open to question, and how should a community decide this?

• How can we develop and act from an ethical base while engaging as citizens in our communities?

As a student in a community-based learning course, you will be asked to be highly reflective about your learning experiences. Often, you will keep a journal or write reflective papers that emphasize various aspects of your learning. You may also be asked to post service-learning blogs or respond to online discussion questions. The goal is to help you cognitively and affectively process your thoughts and feelings about your experience, while using academic content to derive broader insights.

Here’s an example of one way to reflect on your experience. In a senior-level course that provided after-school activities for at-risk students in an urban environment, the learners were asked to examine their experiences from a variety of viewpoints in their reflective journals:

• Describe what you did today.

• What did you see or observe at the site?

• How did you feel about the experience?

• What connections do you find between the experience and course readings?

• What new ideas or insights did you gain?

• What skills can you use and strengthen?

Exercise 1.1: Comparing Classrooms Think back to traditional classrooms in which you have been a student/learner. What responsibilities did you have in this kind of class, and what responsibilities did the instructor have? How do you imagine your role as a student will be different in this community-based experience? What kinds of responsibilities do you imagine that you will have in this class? How about your instructor? The others in your classroom learning community? The community outside your classroom?

Make a list of the activities you did in a traditional classroom and compare those with any of your nontraditional learning experiences. What factors in each environment best facilitated your learning? What factors made it more challenging for you to learn?

• What will you apply from this experience in future work with the community?

Reflecting on our experiences lends new significance to what we are learning. It also allows us to compare initial goals and objectives with eventual outcomes—to assess what we have accomplished. We will cover more about reflection and assessment of our community-based learning experiences in later chapters. For now, let’s turn our thoughts to why colleges and universities offer service-learning courses.

Why Is Service-Learning Required at Some Colleges?

Colleges and universities are increasingly including in their educational mission the preparation of graduates as future citizens. What, really, does this mean? Are colleges merely hoping that you will vote and pay your taxes as contributing members of society? What about job training and preparing you for the workforce? Aren’t you, in fact, spending a lot of time and money on school? If so, why should you be required to perform volunteer service in the community? Isn’t obligatory volunteerism like being an indentured servant? In other words, Are you being forced to work for free?

Perhaps the greatest single resistance voiced in service-learning classes is the argument that service is volunteerism and, by definition, cannot be required. However, in service-learning classes, the good that you will do in your community necessarily includes the learning you will gain as a result of your efforts. The whole point of service-learning is for you to grow in skills and knowledge precisely because you are bringing your capabilities to real-world problems. While you do this, yo...