eBook - ePub

Race, Equity, and the Learning Environment

The Global Relevance of Critical and Inclusive Pedagogies in Higher Education

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Race, Equity, and the Learning Environment

The Global Relevance of Critical and Inclusive Pedagogies in Higher Education

About this book

From the Foreword:

"This volume bridges the gap from thought to action, providing the necessary context for educators around the world to either embrace or recommit to centering race in postsecondary classrooms and engaging in necessary conversations to ensure that students do not leave our institutions the way they came. I applaud the editors of this book as they dare to move beyond the conversation to engage in teaching and learning that reflects how progressive racial understandings promote equity in higher education."--Lori Patton Davis, Associate Professor, Higher Education and Student Affairs, IUPUI

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Race, Equity, and the Learning Environment by Frank Tuitt, Chayla Haynes, Saran Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Higher EducationPART ONE

HOW WE THINK ABOUT OUR WORK

1

ADVANCING A CRITICAL AND INCLUSIVE PRAXIS

Pedagogical and Curriculum Innovations for Social Change in the Caribbean

Saran Stewart

Three years ago, I booked a one-way ticket to Jamaica, my “foreign-homeland.” The term foreign-homeland represents how I view Jamaica as an adult, as opposed to how I viewed it as a child. Some customs and practices I once found normative and comforting I now view as oppressive and intolerable. Upon my arrival, I made several conscious decisions to renegotiate how I operated within the social structures and governance of life at home. To reacclimatize, I had to unlearn privileges, as explained by Spivak (1988, 2004), and understand that I operated within an identity as a knowledge elite. Having earned a doctoral degree, I had become a “power broker” (Gaventa, 1980, p. 28) and had to rationalize how I navigated within that role. I found myself struggling with the term knowledge elite as it represented “the control of knowledge in the hands of the few, in a manner that exercises power over the lives of many” (Gaventa, 1980, p. 30). The power dynamic between student and professor can often be off-balance and result in an exclusive learning environment.

I knew returning to my foreign-homeland, armed with a global perspective of teaching and learning, would challenge the “traditional modes of instruction, which serve to exclude rather than include students” (Danowitz & Tuitt, 2011, p. 43). These challenges echo Freire’s (2005) concept of banking education, which I believe reverberates through the halls of the university where I currently teach:

The teacher teaches and the students are taught; . . . the teacher talks and the students listen—meekly; . . . the teacher chooses the program content, and the students (who were not consulted) adapt to it; . . . the teacher is the subject of the learning process, while the pupils are mere objects. (p. 73)

The difficulty in disrupting the banking system of education (Freire, 2005) is that both the oppressed (i.e., the students) and the oppressor (i.e., the lecturer) can be resistant to change. For example, a first-year postgraduate student visited my office in the middle of the semester, not to discuss her grades or class assignments, but to relay, on behalf of her classmates, that my style of teaching was too “foreign-minded” (having Eurocentric ideals and expectations) and was not welcomed at the university. She said, “Doc, why can’t you be like the other lecturers; just come to class, run through the power point, and give us notes? All these questions, questions about what we think, and group work activities in class; we are not use to that” (personal communication, September 2013). After she left, I reflected on the words of my mentors: “Expect and be prepared to engage student resistance in teaching and learning” (Danowitz & Tuitt, 2011, p. 52).

Despite the research on the benefits and gains of student-centered learning and engaging pedagogical models, lecture-style instruction continues to be the de facto style of higher education teaching around the world (Brown & Atkins, 2002; Chisholm, 2008). Lecture style, although not equated to banking education (Freire, 1993), is reminiscent of shared similarities, such as one-directional learning in which the lecturer (i.e., faculty member, instructor, or teacher) is the subject of knowledge and the students, the objects.

The lectureship instructional design is the customary choice of content delivery in Jamaica’s higher education institutions, in which students attend class with little exchange of ideas or expectation to co-construct knowledge. In the United States, many researchers have debated the need for a more inclusive shift in pedagogy (e.g., Darder, 1996; hooks, 1994; Knefelkamp, 1997; Tuitt, 2003). The debate is further compounded in postcolonial and neocolonial societies, such as Jamaica, in which inherited customs of higher education practice reflect conflicting power dynamics aimed at continuing colonial traditions. Inherited customs, such as the dominance of a patriarchal climate amongst senior administrators and faculty, a lecture–tutorial learning system, and an examinations-driven culture resemble some of the political and ideological struggles of the colonial era. This is the context in which I returned to teach in Jamaica.

Within that context, this chapter examines how I employed a critical and inclusive pedagogy (CIP) framework (Stewart, 2013) to develop pedagogical and curriculum innovations for social change. It is intended as a critical reflection of my experiences teaching at a public regional research university in the Caribbean, which is referred to as the Caribbean University hereafter. I present a hybridized framework to describe how I apply and practice CIP in postgraduate educational research and higher education courses. In doing this, I employ both Alvesson’s (2003) self-ethnography, “to draw attention to one’s own cultural context” (p. 175), and Ellis and Bochner’s (2000) autoethnography in which the researcher–author’s method is to “tell stories about their [his or her] own lived experiences, relating the personal to the cultural” (Richardson, 2000, p. 931). Thereafter, I outline what I believe are movements of social change in my students and conclude by addressing some of the implications for educators who seek to apply the CIP framework (Stewart, 2013) in higher education institutions.

Applying CIP

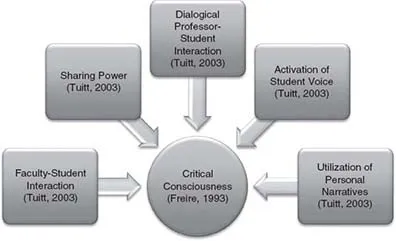

Being trained and prepared for academia by transformative intellectuals, I understood that scholarship should not be devoid of a social and political context. I recognized the need to develop a conceptual and theoretical base in which to engage students in higher education, as co-constructors in the teaching–learning process. It was not enough to develop an inclusive learning environment for my students. I also needed to create a classroom experience that would enable them to attain a heightened awareness for social change. During my doctoral studies, I developed the CIP framework as a guide in which to map core competencies onto a set of teaching practices aimed to foster both critical consciousness and a more inclusive learning environment. My conceptual mapping of a CIP framework centered on the use and application of Tuitt’s (2003) five tenets of inclusive pedagogy to attain Freire’s (2005) ideal of conscientização, or critical consciousness. The framework is highly adaptive to regional context and dependent on the respectful relationship between student and faculty (see Figure 1.1).

Developing Critical Consciousness

I understand critical consciousness as “learning to perceive social, political, and economic status contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” (Freire, 2005, p. 35). Freire (2005) suggested that in order for oppressed persons to truly be liberated, dialectical, and dialogical, they must be able to read the world and not just the word. They must “recognize themselves as the architects of their own cognitive process” (p. 112). In attempting to help my students develop critical consciousness, I expect them to not only learn how to critically view, understand, and debate social, political, and economic contradictions, but also see the self through the self and as the other (adapted from Ellis, 2004). This meta-awareness involves self-reflection and critical pedagogy to guide the process. Furthering this approach, critical reflection is necessary and “is a requirement of the relationship between theory and practice” (Freire, 1998, p. 30). As the lecturer, I am also the oppressor with the assumed sole power to construct knowledge in the class. I control the direction of my students’ learning and can either encourage or diminish inclusion and social change activism. However, the instructor as oppressor must first acknowledge and accept the status of oppressor, even one who may have been oppressed previously, and use authority to facilitate learning, not control it. Additionally, as Freire (1998) explained, “the educator with a democratic vision or posture cannot avoid in his teaching praxis insisting on the critical capacity, curiosity and autonomy of the learner” (p. 33). The educator must be the facilitator of knowledge to guide self-efficacy and respect what students know entering the classroom.

Figure 1.1 Critical–inclusive pedagogical framework.

Note. Adapted from Everything in di Dark Muss Come to Light: A Postcolonial Examination of the Practice of Extra Lessons at the Secondary Level in Jamaica’s Education System, by S. Stewart, 2013 (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest (Order No. 3597983).

Freire (1993) problematized systems of banking education, revealing the inequities, injustices, and misappropriation of teaching and learning in the classroom. He went further in stating, “A characteristic of the ideology of oppression negates education and the knowledge as processes of inquiry” (p. 72). In unveiling the inequities in the education system, Freire then revealed new concepts of pedagogy, homing in on the need for “problem-posing” education that truly transforms rather than transfixes men and women into becoming dialogical (Stewart, 2013). In this regard, Freire acknowledged that the “teacher’s thinking is authenticated only by the authenticity of the student’s thinking” (1993, p. 77). Accordingly, I am accountable for my students’ learning and, in that, also responsible for how we, together, co-construct knowledge in the classroom. By developing critical consciousness, students develop agency when they leverage their voices to speak out and purposely act against oppressive systems of society, including education. In my experience, developing critical consciousness has no timeline and can resemble an oscillating pendulum, because in any given moment, one’s critical consciousness can shift according to recognition of himself or herself in society amid revolving societal changes.

Inclusive Pedagogy at the Caribbean University

In the first couple of months as a newly minted lecturer, I realized that if I were to navigate the roles of bureaucratic authority, I had to tactically infuse the framework without disrupting the norm completely. I set out not to demand and overhaul years of banking education (Freire, 1993), but to demonstrate, as a “tempered radical” (Meyerson, 2003), the subtle inclusion of problem-posing education (Freire, 1993). Unfortunately, my subtle attempts to infuse the CIP framework were not met with open arms. In meetings, any suggestions I made as a new hire in academia were dismissed as being “foreign-minded” and juvenile. I was reminded of being a young woman in a patriarchal environment, led by men but operated by women. The very women who were oppressed had become oppressive. Women who had been overlooked for promotions and/or paid less than their male counterparts had arguably internalized years of oppression. Seemingly, the internalized oppression was unleashed on young and naïve hires like myself. In the first year, my suggestions for pedagogical and curriculum improvements were constantly overlooked. I was told that the majority of my students were classroom teachers in local primary and secondary schools, that they would remain that way after graduating with their master’s degrees, and that further aspirations to doctoral work or employment outside of the country and industry were unrealistic.

As a means to disrupt these forms of “academic orthodoxy” (Chisholm, 2008, p. 328), I employed Tuitt’s (2003) concept of inclusive pedagogy derived from an amalgamation of critical and transformative pedagogical models—for example, Banks and McGee’s (1997) equity pedagogy, Freire’s (1993) pedagogy of the oppressed, Giroux’s (1992) border pedagogy, and hooks’ (1994) engaged pedagogy and transformative education. Inclusive pedagogy includes the following key tenets: (a) faculty–student interaction, (b) sharing power, (c) dialogical professor–student interaction, (d) activation of student voice, and (e) utilization of personal narratives (Tuitt, 2003). It is transformative as a holistic concept and a methodological approach because it provides key principles to guide teaching practices to make the learning environment inclusive and engaging. In practicing the CIP framework (Stewart, 2013), I made conscious decisions not to dictate the class, but to facilitate and guide learning at the students’ pace, so as to foster an inclusive learning environment where all voices were respected and encouraged. I asked more questions than time allowed and did not provide finite answers, but let students question alternatives to answers. I allowed multiple pathways to arrive at an answer so as to encourage divergent thinking. In the next section, I explain how Tuitt’s (2003) tenets manifest in my teaching, which is informed by the CIP framework (Stewart, 2013).

Realizing a Critical and Inclusive Praxis

The first tenet of inclusive pedagogy, faculty–student interaction, promotes positive relationships between student and faculty in which trust is earned and reciprocated. The interaction between faculty and student is encouraged inside and outside the classroom to foster “positive social interactions” (Tuitt, 2003, p. 247). Throughout my tenure at Caribbean University, I found constant and consistent communication to be key factors in promoting this level of interaction. I found myself engaging with students using various forms of instant messaging, live video chats, and social media, which resulted in mini-advising sessions. Being available to students in various modes of communication allowed for increased access to mentoring and advising.

The second tenet, sharing power, debunks the role of the professor as the sole constructor of knowledge. Instead, both student and faculty are expected to co-construct knowledge and are equally responsible to contribute to the process of teaching and learning in the classroom. As part of the course assessment, I used interactive group-led class activities in which students were required to take sections of the core topics of the course and develop classroom activities to teach said topics. This allowed students to demonstrate their teaching styles and helped to foster a sense of ownership of the course material. Students were guided to assess their individual learning styles and incorporate techniques to demonstrate each. Moreover, students were expected to coteach course content as part of the assignments and peer-review other students’ work. Each semester, there was resistance and rejection of the newly required responsibilities of the students in co-constructing the learning environment and knowledge generated in my courses. The students were initially resolved to engage minimally, take notes, and do what they were told. I was transparent about having them recognize their learned behavior as a legacy of banking education by having them read excerpts from Tuitt’s (2003) and Freire’s (1993) works (to name a few). In the past, I hosted video-conference sessions with Tuitt on inclusive pedagogy, as well as invited him to speak in-person on campus. Demystifying scholarly research and making it applicable and embedded in lived experiences cements to the students a greater responsibility for their own learning.

The third tenet, dialogical professor–student interaction, is often challenging to implement in learning environments where knowledge is disseminated in formal lecture styles and regulated by top-down institutional policies. This tenet advocates for constant, reciprocal dialogue and discourse that is both respectful and problem posing. The discourse thereby allows for differing perspectives and multiple “truths,” with an aim of creating “collaborative learning environments” (Tuitt, 2003, p. 248). I encouraged my students to interrogate my views and respectfully challenge course content and literature by delving even deeper into the literature to propose counterarguments. I found that the organizational culture of the institution often made it difficult for students to be comfortable with disagreeing with the professor and contributed to accepted silence.

To disrupt the silence, my aims were to create trusting learning environments in which students were free to express their varying and opposing opinions and engage in critical discourse. To do this, the students and I collaboratively set the norms and aims of the class at the start of the semester. Thereafter, we held each other accountable to those aims throughout the course. This disruption essentially led to the development of the fourth tenet, activation of student voice, which Tuitt (2003) explained: “By having a voice, students can bring into the classroom the world as they have experienced it” (p. 250)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: How We Think About Our Work

- Part Two: How We Engage In Our Work

- Part Three: Measuring The Impact Of Our Work

- Conclusion

- Editors And Contributors

- Index

- BackCover