![]()

1

FIVE ESSENTIAL PRINCIPLES

ABOUT WRITING TRANSFER

Jessie L. Moore

Writing curricula in higher education are constructed under a foundational premise that writing can be taught—and that writing knowledge can be “transferred” to new contexts. In the United States, first-year composition is often required for all students with the assumption that what is learned there will transfer across “critical transitions” to other course work, to postgraduation writing in new workplaces, or to writing in graduate or professional programs. Arguably, all of modern education is based on the broader assumption that what one learns here can transfer over there, across critical transitions. But what do we really know about transfer, in general, and writing transfer, in particular?

From 2011 to 2013, 45 writing researchers from 28 institutions in 5 countries participated in the Elon University’s Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer research seminar. As part of the seminar, Elon’s Center for Engaged Learning facilitated international, multi-institutional research about writing transfer and fostered discussions about recognizing, identifying enabling practices for, and developing working principles about writing transfer. Over the final year of the seminar, participants developed the Elon Statement on Writing Transfer (2015) to summarize and synthesize the seminar’s overarching discussion about writing and transfer, not as an end point but in an effort to provide a framework for continued inquiry and theory building (Anson & Moore, 2016). Although that document exists as a resource for disciplinary scholars in writing studies, this collection focuses on five essential principles about writing transfer that should inform decision-making by all higher education stakeholders. Part One: Critical Sites of Impact includes six chapters that examine programmatic and curricular sites that could be enriched by additional focus on these essential principles for writing transfer. Part Two: Principles at Work: Implications for Practice includes six case studies that illustrate the essential principles’ implications for practice, curriculum design, and/or policy.

This collection concisely summarizes what we know about writing transfer and explores the implications of writing transfer research for universities’ institutional decisions about writing across the curriculum requirements, general education programs, online and hybrid learning, outcomes assessment, writing-supported experiential learning, ePortfolios, first-year experiences, and other higher education initiatives. Ultimately, this brief volume aims to make writing transfer research accessible to administrators, faculty decision makers, and other stakeholders across the curriculum who have a vested interest in preparing students to succeed in their future writing tasks in academia, the workplace, and their civic lives.

What Is Writing Transfer?

Briefly, writing transfer refers to a writer’s ability to repurpose or transform prior knowledge about writing for a new audience, purpose, and context. Writing transfer research builds on broader studies in educational psychology and related fields on transfer of learning, and many of the terms used to describe writing transfer are borrowed from these other realms. The following is a quick primer on some of the terms and concepts used in this collection.

David Perkins, a founding member of Harvard’s Project Zero, and Gavriel Salomon, an educational psychologist, coined the two sets of terms often invoked in transfer studies, including writing transfer studies: near transfer and far transfer, and high-road transfer and low-road transfer (see Perkins & Salomon, 1988, 1989, 1992; Salomon & Perkins, 1989). Near transfer refers to carrying prior knowledge or skill across similar contexts (e.g., driving a truck after driving a car), whereas far transfer refers to carrying knowledge across different contexts that have little, if any, overlap (e.g., applying chess strategies to a political campaign). Whereas this first set of terms focuses on the contexts for transfer, the second set focuses on the learner’s use of knowledge in those contexts. In low-road transfer, something is practiced in a variety of contexts until it becomes second nature and is automatically triggered when a new context calls on our use of the knowledge, skill, or strategy. High-road transfer, in contrast, requires the learner’s mindful abstraction to identify relevant prior knowledge and apply it in the new context.

King Beach, a developmental psychologist, introduced the idea of consequential transitions as an alternate way to conceptualize use of prior knowledge. Beach (2003) suggested that transition refers to the generalization of knowledge across contexts. A consequential transition “is consciously reflected on, struggled with, and shifts the individual’s sense of self or social position” (p. 42). Building on this concept, Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Yrjö Engeström (2003), from the Center for Research on Activity, Development and Learning, situated consequential transitions within activity systems, which shape and are shaped by learners and other participants. Successful transfer requires learners to implement new models based on their analyses of prior knowledge and to consolidate new and prior practices. Learners become boundary crossers and change agents, intertwined with evolving social contexts.

The Bioecological Model of Human Development, theorized by Urie Bronfenbrenner and colleagues, and Etienne Wenger’s work on Communities of Practice help educators understand learners’ interactions with those social contexts. The Bioecological Model attends to the context of learner development, extending the focus on the individual in the system to consider the impact of the individual’s interactions with his or her context over time (see, e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Applied to transfer studies, the bioecological model suggests that the learner’s dispositions can impact willingness to engage with transfer and can have generative or disruptive impacts on the learner’s context. Similarly, Etienne Wenger and others suggested that communities of practice are collectives of individuals and groups sharing values, goals, and interests, with the community shaping the individual and the individual shaping the community (see, e.g., Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002). Communities include both novices and experts. Part of the dialogic process of moving from novice to expert involves learning how to learn within communities. As we think about learning transfer, then, we should look for the enabling practices that help students develop those learning-how-to-learn strategies that apply across contexts or communities.

Jan (Erik) Meyer and Ray Land (2006), building on David Perkins’s notion of troublesome knowledge, challenged educators to identify concepts central to epistemological participation in disciplines and interdisciplines. Often these threshold concepts are transformative; when learners fully grasp the concepts, their disciplinary view changes. Yet, that transformative nature also creates liminality, as students grapple with ideas or new knowledge that may be counterintuitive or inconsistent with their prior knowledge. If students successfully work through the transitional space of making sense of the threshold concept, it likely will have an integrative impact, helping students synthesize other disciplinary knowledge and concepts. Threshold concepts typically are implicit markers of disciplinary knowledge, but once educators explicitly identify those threshold concepts that are central to meaning-making in their fields (i.e., their communities of practice), they can prioritize teaching these concepts, in turn increasing the likelihood that students will carry an understanding of these core concepts into future course work and contexts. Writing studies scholars Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle (2015) have led efforts to identify the threshold concepts for writing, and the essential principles in this volume in essence reflect the threshold concepts for designing university curricula and teaching for writing transfer.

Successful Writing Transfer Requires Transforming Prior Knowledge

Principle 1: Successful writing transfer requires transforming or repurposing prior knowledge (even if only slightly) for a new context to adequately meet the expectations of new audiences and fulfill new purposes for writing. “Successful writing transfer occurs when a writer can transform rhetorical knowledge and rhetorical awareness into performance” (2015, p. 4). Students facing a new and difficult writing task draw on previous knowledge about genre conventions (e.g., reader expectations for memos or lab reports or patient reports), logical appeals, organization, citation conventions, and much more. They repurpose prior writing strategies, ranging from brainstorming activities to strategies for eliciting and responding to feedback on writing in progress. Whether crossing concurrent contexts (e.g., courses in the same semester, or university course work and a part-time job) or sequential contexts (e.g., courses in a major’s or minor’s scaffolded sequence, high school to college, or a university degree program to a postgraduation job), individuals may engage in both routinized (low-road) and transformative (high-road) forms of transfer as they draw on and use prior knowledge about writing.

When students tap that prior knowledge, they must transform or repurpose it, if only slightly. Writing studies scholars Mary Jo Reiff and Anis Bawarshi (2011), for instance, introduced the idea of “not-talk.” They suggested that one part of repurposing prior knowledge is recognizing when a new task calls on writers to compose a genre that is unlike a genre composed before. In other words, successful transfer requires writers to recognize when the new task is not a five-paragraph essay, not a literary analysis, not a lab report, not a memo, and so forth.

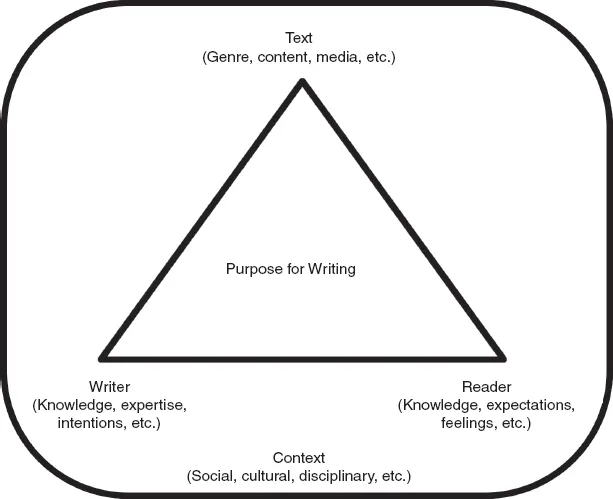

Of course, genre knowledge is only one element of each rhetorical situation for writing. Successful writers also are attentive to the knowledge and expertise they bring to a writing task, the expectations and backgrounds of their readers, their available choices for the content and form of the actual text, and the larger context encompassing their communication. Being attentive to this rhetorical situation (as illustrated in Figure 1.1) enables writers to make strategic choices about their prior knowledge that might be applicable—or adaptable—to each new purpose for writing.

Figure 1.1. Elements of a rhetorical situation for writing.

Writing studies scholar Rebecca Nowacek (2011) highlighted the challenges inherent in transforming and repurposing writing knowledge for new rhetorical situations. Because students’ transformation attempts typically are not visible to others, teachers often do not recognize those attempts. At the same time, the attempted transformation might not be appropriate for the new rhetorical situation, course, or writing context. Yet, if a teacher does not recognize that a student attempted to transfer prior knowledge, feedback to the student likely won’t include strategies for more effective repurposing of that prior knowledge.

Given the significance of prior knowledge, higher education curricula must be attentive to the foundations laid in secondary curricula (see Farrell, Kane, Dube, & Salchak, this volume), in first-year courses (see Boyd, this volume; Gorzelsky, Hayes, Jones, & Driscoll, this volume; Robertson & Taczak, this volume), and in prerequisites throughout students’ course work.

Writing Transfer Is a Complex Phenomenon

Principle 2: Writing transfer is a complex phenomenon and understanding that complexity is central to facilitating students’ successful consequential transitions, whether among university writing tasks or between academic and workplace or civic contexts. Writing transfer is inherently complex. It involves approaching new and unfamiliar writing tasks through applying, remixing, or integrating previous knowledge, skills, strategies, and dispositions. If the new context does not trigger automatic use of prior knowledge, as in low-road transfer, writers must systematically reflect on past writing experiences that might be relevant, cull the prior knowledge that contributed to the success (or failure) of those past experiences, and adapt the knowledge for the new circumstances (high-road transfer).

Writing studies scholars Liane Robertson, Kara Taczak, a...